Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

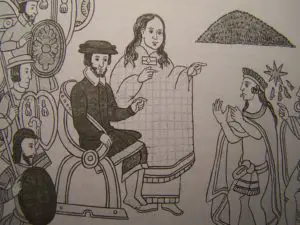

November 8th 1519 will always be remembered as one of the most important dates in the history of Mexico and in the history of the world. It was on this day that Aztec Emperor Montezuma invited the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men into the imperial capital city of Tenochtitlan as honored guests. Many of the men accompanying Cortés had traveled to the largest cities of the Old World, such as Rome, Jerusalem and Constantinople, but even the most seasoned travelers among them were not prepared for the magnificence, abundance and opulence they would experience in the Aztec capital. Tenochtitlan, the shiny city of tall pyramids, broad avenues and marketplaces overflowing with riches, was the center of a vast empire that had existed for almost 200 years. The Aztecs controlled most of central Mexico and their territory went as far north as the Oxtlipa lands in the modern state of San Luís Potosí and as far south as a disconnected cacao-producing area called Xoconochco in the modern country of Guatemala and the modern Mexican state of Chiapas. Trade routes extended farther and connected the Aztec Empire with far-flung areas of Central America and the modern day American states of New Mexico, Arizona and Texas. Most all goods, tribute and talent in the Aztec territories eventually flowed back to that capital city in the center of the lake which so impressed the Spanish newcomers. Historians estimate that hundreds of thousands of people of dozens of ethnic groups lived under either direct Aztec rule or in some sort of state of subjugation through tribute. As the Spanish found out on their long march to the imperial capital, many people and entire groups of people, did not enjoy living a subjugated existence under the Aztec jackboot. Resistance to Aztec rule throughout Mexico was common and to quell the rebellions and to expand their territory, the Aztecs developed a superior military fighting force. Part of this superior military force included elite special ops groups collectively known as the Eagle and Jaguar Knights. In the Aztec language of Nahuatl, they were known as cuauhtli and ocelotl respectively. Together, the knights were known collectively as cualtlocelotl.

November 8th 1519 will always be remembered as one of the most important dates in the history of Mexico and in the history of the world. It was on this day that Aztec Emperor Montezuma invited the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men into the imperial capital city of Tenochtitlan as honored guests. Many of the men accompanying Cortés had traveled to the largest cities of the Old World, such as Rome, Jerusalem and Constantinople, but even the most seasoned travelers among them were not prepared for the magnificence, abundance and opulence they would experience in the Aztec capital. Tenochtitlan, the shiny city of tall pyramids, broad avenues and marketplaces overflowing with riches, was the center of a vast empire that had existed for almost 200 years. The Aztecs controlled most of central Mexico and their territory went as far north as the Oxtlipa lands in the modern state of San Luís Potosí and as far south as a disconnected cacao-producing area called Xoconochco in the modern country of Guatemala and the modern Mexican state of Chiapas. Trade routes extended farther and connected the Aztec Empire with far-flung areas of Central America and the modern day American states of New Mexico, Arizona and Texas. Most all goods, tribute and talent in the Aztec territories eventually flowed back to that capital city in the center of the lake which so impressed the Spanish newcomers. Historians estimate that hundreds of thousands of people of dozens of ethnic groups lived under either direct Aztec rule or in some sort of state of subjugation through tribute. As the Spanish found out on their long march to the imperial capital, many people and entire groups of people, did not enjoy living a subjugated existence under the Aztec jackboot. Resistance to Aztec rule throughout Mexico was common and to quell the rebellions and to expand their territory, the Aztecs developed a superior military fighting force. Part of this superior military force included elite special ops groups collectively known as the Eagle and Jaguar Knights. In the Aztec language of Nahuatl, they were known as cuauhtli and ocelotl respectively. Together, the knights were known collectively as cualtlocelotl.

As the Aztecs were constantly in a state of war with their neighbors, all able men were required to undergo basic military training. Women never went to battle and there were no exceptions. Basic combat skills were usually learned by Aztec boys in their homes or neighborhoods but by the age of 14 military education became more strict and serious and shifted to local temples. Those boys who displayed exceptional skill were chosen to become future Eagle and Jaguar Knights. The “knights in training,” who mostly hailed from the noble classes, were supervised by more experienced warriors and training was more rigorous. In addition to a more attentive training regimen, those slotted to be knights were also educated in other disciplines such as religion, politics and history. Formal military service usually began at age 17 and many of the boys in the knights training program fought in major battles with their older warrior mentors, although they were relegated to the rear ranks. Once the young recruit captured his first prisoner he was given warrior status. It was only after capturing between 12 and 20 prisoners that a warrior could be considered a full-fledged Eagle or Jaguar Knight. Those exceptional knights could also join two more elite groups called Otontin and the Cuauhchicqueh. The latter group means in English, “The Shaved Ones.” The commanders of the knights and those who committed an exceptional amount of extraordinary acts in battle usually belonged to these super elite groups. They were distinguished from the others by a special shield with an insignia of 4 crescents in addition to a more elaborate military uniform. Those who did not go through the formal knights training program from adolescence and who were not from the noble class could also become Jaguar and Eagle Knights, although it was more uncommon. Through extreme and distinguished valor and courage on the battlefield a commoner could elevate himself to the ranks of the knights. Many people born into the lower classes in Aztec society saw the military as a way to increase their social status. As a consequence, the Aztec military machine was full of many ambitious and dedicated men who were willing to fight to the death for the empire.

As the Aztecs were constantly in a state of war with their neighbors, all able men were required to undergo basic military training. Women never went to battle and there were no exceptions. Basic combat skills were usually learned by Aztec boys in their homes or neighborhoods but by the age of 14 military education became more strict and serious and shifted to local temples. Those boys who displayed exceptional skill were chosen to become future Eagle and Jaguar Knights. The “knights in training,” who mostly hailed from the noble classes, were supervised by more experienced warriors and training was more rigorous. In addition to a more attentive training regimen, those slotted to be knights were also educated in other disciplines such as religion, politics and history. Formal military service usually began at age 17 and many of the boys in the knights training program fought in major battles with their older warrior mentors, although they were relegated to the rear ranks. Once the young recruit captured his first prisoner he was given warrior status. It was only after capturing between 12 and 20 prisoners that a warrior could be considered a full-fledged Eagle or Jaguar Knight. Those exceptional knights could also join two more elite groups called Otontin and the Cuauhchicqueh. The latter group means in English, “The Shaved Ones.” The commanders of the knights and those who committed an exceptional amount of extraordinary acts in battle usually belonged to these super elite groups. They were distinguished from the others by a special shield with an insignia of 4 crescents in addition to a more elaborate military uniform. Those who did not go through the formal knights training program from adolescence and who were not from the noble class could also become Jaguar and Eagle Knights, although it was more uncommon. Through extreme and distinguished valor and courage on the battlefield a commoner could elevate himself to the ranks of the knights. Many people born into the lower classes in Aztec society saw the military as a way to increase their social status. As a consequence, the Aztec military machine was full of many ambitious and dedicated men who were willing to fight to the death for the empire.

The Eagle and Jaguar Knights always fought in the front lines and dressed in battle regalia appropriate for their type of knighthood. For example, the Eagle Knights wore a helmet which looked like an open beak of an eagle along with feathers of the majestic bird. The Jaguar Knights wore pelts of the great cat with their heads appearing to come out of the mouth of the jaguar. The costumes of the warriors became more elaborate as rank increased. This visual spectacle on the battlefield had a psychological effect to intimidate the enemy. All knights wore a thickly woven cotton breastplate that served as a form of armor and carried decorated shields called chimalli. Leather straps hanging off the legs provided some protection to the lower areas of the body.

The Eagle and Jaguar Knights always fought in the front lines and dressed in battle regalia appropriate for their type of knighthood. For example, the Eagle Knights wore a helmet which looked like an open beak of an eagle along with feathers of the majestic bird. The Jaguar Knights wore pelts of the great cat with their heads appearing to come out of the mouth of the jaguar. The costumes of the warriors became more elaborate as rank increased. This visual spectacle on the battlefield had a psychological effect to intimidate the enemy. All knights wore a thickly woven cotton breastplate that served as a form of armor and carried decorated shields called chimalli. Leather straps hanging off the legs provided some protection to the lower areas of the body.

This elite fighting force also used a wide array of weapons. In battle, the Aztecs’ primary objective was to get as many captives as possible, to fuel the need for human sacrifice back in the imperial capital. As a consequence, many of the weapons used in battle were meant to stun instead of to kill. The weapon of choice among the Eagle and Jaguar Knights was the macahuitl. This was a flat-faced club which looked much like a short boat oar or cricket bat. On the sides of the macahuitl were inlaid pieces of sharp volcanic glass also known as obsidian. The warrior could give the enemy a blow to the head with the flat-faced part of the weapon, or in more dangerous situations where killing the opponent was required, the macahuitl could be used in a slicing motion much like a sword. In addition to this flat-faced club, the knights’ weapons arsenal included a variety of other things. Slings made of cactus fiber were used to hurl rocks at the enemy. 5-foot-long bows called tlahuitolli were strung with animal sinew and used wooden arrows tipped with stone and fletched with turkey feathers. A  tecaptl was a dagger with an 8-inch handle and tipped with a flint blade used mostly in hand-to-hand combat. The knights also made use of the itztopilli an ax shaped like a tomahawk with a copper or stone head, sharp on one side and blunt on the other. Those in the front ranks used a unique type of flat wooden spear thrower called an atlatl which allowed the spear to travel a longer distance. The spear used in the atlatl was called a tlacochtli and could be as long as 6 feet. For ambush fighting, the knights also used a blowgun and darts tipped with a poison made from the secretions of a tree frog. Through the use of these weapons, the knights were well trained in long-distance, face-to-face and clandestine combat.

tecaptl was a dagger with an 8-inch handle and tipped with a flint blade used mostly in hand-to-hand combat. The knights also made use of the itztopilli an ax shaped like a tomahawk with a copper or stone head, sharp on one side and blunt on the other. Those in the front ranks used a unique type of flat wooden spear thrower called an atlatl which allowed the spear to travel a longer distance. The spear used in the atlatl was called a tlacochtli and could be as long as 6 feet. For ambush fighting, the knights also used a blowgun and darts tipped with a poison made from the secretions of a tree frog. Through the use of these weapons, the knights were well trained in long-distance, face-to-face and clandestine combat.

When not engaged in battle, the Eagle and Jaguar Knights enjoyed their privileged status in Aztec society. In a culture that values war, the warriors will be held in very high regard and the Aztec culture was no exception here. While many men in Aztec society went to battle, the knights were seen as the only full-time, professional soldiers. With a man’s commission as a knight, the emperor also bestowed on him a piece of land that he owned for life and could be passed down to his children. Any profit made by economic activities on that land was for the sole use of the knight and could not be taxed by the empire. The Eagle and Jaguar Knights were allowed to have multiple wives and were able to dine in the imperial palace, eating special foods usually reserved for the nobility. They could drink alcohol in public and wear sandals in designated royal areas. They were also permitted to wear jewelry and special clothing in public if they desired. Aztec society as a whole gave much respect to the knights and most every little Aztec boy aspired to be one.

Upon entering the center of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1519, the Spanish were shown the various buildings that made up the civic-ceremonial heart of the empire. Next to the Templo Mayor, or principal pyramid in the center of the imperial capital was what was called The House of Eagles. It was in this large structure of broad patios and meeting rooms where the Eagle and Jaguar Knights congregated for ceremonies and rituals, and engaged in meditation and prayer to the god of war Huitzilopochtli, one of the main ancient Mexican gods who was born ready for battle in full warrior regalia. The House of Eagles was first built in the year 1430 and greatly expanded 40 years later under the direction of Emperor Axayócatl who expanded the Aztec Empire and increased the number of men serving in the military. The building was renovated again in the year 1500 as the empire grew and more wealth flowed back to Tenochtitlan. In 1521 the majestic House of Eagles became one of the first casualties of the Spanish Conquest. The Spanish completely destroyed this noble place and they built a church dedicated to Saint James the Apostle on top of its ruins, and thus, the mighty Aztec knights were buried for good.

Upon entering the center of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1519, the Spanish were shown the various buildings that made up the civic-ceremonial heart of the empire. Next to the Templo Mayor, or principal pyramid in the center of the imperial capital was what was called The House of Eagles. It was in this large structure of broad patios and meeting rooms where the Eagle and Jaguar Knights congregated for ceremonies and rituals, and engaged in meditation and prayer to the god of war Huitzilopochtli, one of the main ancient Mexican gods who was born ready for battle in full warrior regalia. The House of Eagles was first built in the year 1430 and greatly expanded 40 years later under the direction of Emperor Axayócatl who expanded the Aztec Empire and increased the number of men serving in the military. The building was renovated again in the year 1500 as the empire grew and more wealth flowed back to Tenochtitlan. In 1521 the majestic House of Eagles became one of the first casualties of the Spanish Conquest. The Spanish completely destroyed this noble place and they built a church dedicated to Saint James the Apostle on top of its ruins, and thus, the mighty Aztec knights were buried for good.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

Handbook to Life in the Aztec World by Manuel Aguilar Moreno

The Maya, Aztecs and their Predecessors by Muriel Porter Weaver

“History on the Net” website

6 thoughts on “The Eagle and Jaguar Knights”

They were distinguished from the others by a special shield with an insignia of 4 crescents in addition to a more elaborate military uniform.

I am very interested in the information contained in this post. The information contained in this post inspired me to generate research ideas. Thank You.

Glad it helped!

thanks

thanks

very nice information