Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

A former soldier in the army of Emperor Maximilian, Teoberto Maler, returned to Mexico from Europe in 1884 after settling his father’s estate. Maler had inherited a small fortune. With no financial worries, he decided to move to the Yucatán and devote his life to the study of the ancient Maya. Before the death of his father Maler had already gotten his feet wet exploring the major Maya sites of Palenque and Mitla. In his return trip he had the intention to go deeper into the jungles to explore sites that were little visited or yet unknown. Although he never made it to the site of Edzná, he was the first person to write about the lost city and share it with the outside world, as it had been described to him by villagers who had visited these mysterious ruins which lay deep in the jungle. This was the year 1887. The next time Edzná would show up on the radar was in 1906 when workers at the nearby Hontun Hacienda briefly explored the site and reported it to government authorities. The next official visitors to this enigmatic place arrived in 1927, when formal scientific excavations began.

A former soldier in the army of Emperor Maximilian, Teoberto Maler, returned to Mexico from Europe in 1884 after settling his father’s estate. Maler had inherited a small fortune. With no financial worries, he decided to move to the Yucatán and devote his life to the study of the ancient Maya. Before the death of his father Maler had already gotten his feet wet exploring the major Maya sites of Palenque and Mitla. In his return trip he had the intention to go deeper into the jungles to explore sites that were little visited or yet unknown. Although he never made it to the site of Edzná, he was the first person to write about the lost city and share it with the outside world, as it had been described to him by villagers who had visited these mysterious ruins which lay deep in the jungle. This was the year 1887. The next time Edzná would show up on the radar was in 1906 when workers at the nearby Hontun Hacienda briefly explored the site and reported it to government authorities. The next official visitors to this enigmatic place arrived in 1927, when formal scientific excavations began.

The name of this city, Edzná, is a modern name given to the ruins by locals. It was a corrupted form of the Chontal Maya name Itzná, which meant “House of the Itzas” which could be translated to “House of the Magic” or “House of the Waters,” depending on who you ask. Fortunately for people living in the modern era, the people of Edzná left behind a rich written history. The original name of this impressive city was Wakab’ Nal, or “Land of the Seven Provinces.”

Archaeologists believe that the first people to settle at Edzná began building crude residences and temples at the site at around 600 BC. At about 300 BC the building of monumental structures began in what researchers refer to as the Petén Style. The Petén region, for which the style was named, comprises the northern part of modern-day Guatemala, hundreds of miles away from Edzná. This is why some buildings with roof combs at Edzná resemble those at Tikal. Early in the excavation of Edzná, researchers theorized that the site could have been a colony of Tikal or may have been linked to some of the other sites in northern Guatemala either by trade or through royal lineages. Their suspicions were correct when Maya epigraphers began the painstaking, but exciting, task of translating the hieroglyphs found throughout the city. Ix Jut Chanek, the wife of Edzna’s second ruler to be identified, a man named Siyaj Chan K’awii, used as part of her personal title the emblem glyph of the city of Itzan, which is in the Petén region of Guatemala. Some researchers believe that Lady Ix Jut Chanek had considerable power in the city of Edzná and may have even been considered its co-ruler when her husband had formal control of the city from 636 AD to 649 AD. In whatever case, the city’s link to faraway lands is well established and very evident in this  important first phase of Edzná’s development. The mid-600s saw the peak of monumental construction at the city. The inauguration of a hieroglyphic stairway and other major buildings bear the date of 652 AD. A few decades later, by the end of the 600s AD, the city fell under the influence of Calakmul, a powerful Maya kingdom that was the subject of Mexico Unexplained Episode number 219: https://mexicounexplained.com/calakmul-kingdom-of-the-snake/ Inscriptions on a hieroglyphic stairway and writing on other monuments indicate the powerful king of Calakmul, Yuknoom Chʼeen the Second, was also ruler or Edzná. During this period, the architecture of new buildings at Edzná changed to the more localized Puuc style. In the early 700s AD some researchers believe that Edzná may have reasserted its independence, as many monuments extol the victories of Edzná’s kings over foreign enemies, complete with illustrations of captives alongside emblems of their respective cities. The 700s AD saw little building or creation of inscriptions at the site. In the year 790 the written record picks up again with a stela commissioned by King Aj Koht Chowa’ Naahkan. Researchers point out that the style of this stela – from the way the inscriptions look to the attire of the king – point to influences from the coastal areas of the Gulf of Mexico. The last inscription containing a date at Edzná shows the year 869 AD. It references the city’s last known rulers, King Ajan and his wife Queen Ix K‘ihna‘. Like most sites in the region, Edzná seems to have lost most of its luster by the year 900 and the city was mostly abandoned as part of the Classic Maya Collapse. The city maintained a fraction of its former population until a renaissance hit the Yucatán with the rise of such regional powers as Chichén Itzá. By 1100 AD, after two hundred years of languishing, Edzná came to life again. Most researchers believe that this was due to a strong infusion of culture from central Mexico often attributed to the Toltec civilization. It was at this time when the third architectural style debuted at Edzná, giving it a more central Mexican look like what is found at Chichén Itzá. The renaissance at Edzná would last a few hundred years with the site rapidly losing population throughout the 1400s. By the time Christopher Columbus set foot in the New World, the last person left Edzná and figuratively turned off the lights for the last time.

important first phase of Edzná’s development. The mid-600s saw the peak of monumental construction at the city. The inauguration of a hieroglyphic stairway and other major buildings bear the date of 652 AD. A few decades later, by the end of the 600s AD, the city fell under the influence of Calakmul, a powerful Maya kingdom that was the subject of Mexico Unexplained Episode number 219: https://mexicounexplained.com/calakmul-kingdom-of-the-snake/ Inscriptions on a hieroglyphic stairway and writing on other monuments indicate the powerful king of Calakmul, Yuknoom Chʼeen the Second, was also ruler or Edzná. During this period, the architecture of new buildings at Edzná changed to the more localized Puuc style. In the early 700s AD some researchers believe that Edzná may have reasserted its independence, as many monuments extol the victories of Edzná’s kings over foreign enemies, complete with illustrations of captives alongside emblems of their respective cities. The 700s AD saw little building or creation of inscriptions at the site. In the year 790 the written record picks up again with a stela commissioned by King Aj Koht Chowa’ Naahkan. Researchers point out that the style of this stela – from the way the inscriptions look to the attire of the king – point to influences from the coastal areas of the Gulf of Mexico. The last inscription containing a date at Edzná shows the year 869 AD. It references the city’s last known rulers, King Ajan and his wife Queen Ix K‘ihna‘. Like most sites in the region, Edzná seems to have lost most of its luster by the year 900 and the city was mostly abandoned as part of the Classic Maya Collapse. The city maintained a fraction of its former population until a renaissance hit the Yucatán with the rise of such regional powers as Chichén Itzá. By 1100 AD, after two hundred years of languishing, Edzná came to life again. Most researchers believe that this was due to a strong infusion of culture from central Mexico often attributed to the Toltec civilization. It was at this time when the third architectural style debuted at Edzná, giving it a more central Mexican look like what is found at Chichén Itzá. The renaissance at Edzná would last a few hundred years with the site rapidly losing population throughout the 1400s. By the time Christopher Columbus set foot in the New World, the last person left Edzná and figuratively turned off the lights for the last time.

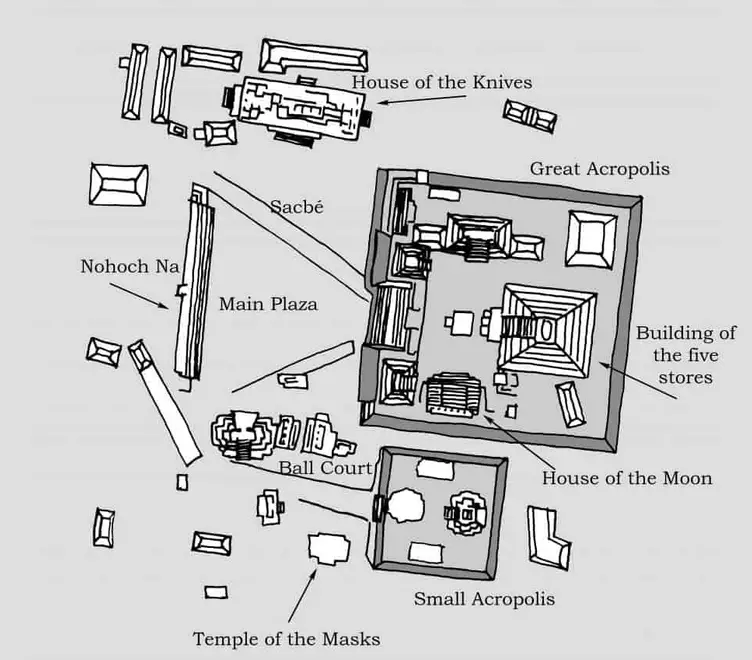

So, what does this intriguing city in the jungle look like? Archaeologists and tourists alike have described Edzná as everything from “magnificent” to “amazing.” There are several major elements of the city worth noting here. The first is the Main Plaza or Gran Plaza. Located in the heart of Edzná, the Main Plaza is an expansive courtyard surrounded by monumental structures, each bearing witness to the city’s grandeur. It measures 538 feet long by 303 feet wide. Dominating the plaza is the Acropolis, an imposing structure that served as a ceremonial and administrative center. Its multiple levels and intricate stairways offer a commanding view of the entire city. Overlooking the eastern side of the Main Plaza stands Edzná’s Great Pyramid or the Pyramid of the Five Stories, called just “Cinco Pisos” in Spanish. Towering over 100 feet tall, this step pyramid rises dramatically, with each tier representing a different stage in Edzna’s history, according to some researchers. A great staircase, studded with hieroglyphs, goes from the main plaza to the temple structure on the top of the pyramid. This temple is crowned with a combed roof that adds 19 more feet to it and is very reminiscent of the main pyramid at Tikal. This pyramid has 27 different rooms, and archaeologists believe that they were used for religious or governmental purposes. There are many other intricate details found on this pyramid, some of which were added during the last “renaissance” phase of the city corresponding to the rise of Chichén Itzá.

So, what does this intriguing city in the jungle look like? Archaeologists and tourists alike have described Edzná as everything from “magnificent” to “amazing.” There are several major elements of the city worth noting here. The first is the Main Plaza or Gran Plaza. Located in the heart of Edzná, the Main Plaza is an expansive courtyard surrounded by monumental structures, each bearing witness to the city’s grandeur. It measures 538 feet long by 303 feet wide. Dominating the plaza is the Acropolis, an imposing structure that served as a ceremonial and administrative center. Its multiple levels and intricate stairways offer a commanding view of the entire city. Overlooking the eastern side of the Main Plaza stands Edzná’s Great Pyramid or the Pyramid of the Five Stories, called just “Cinco Pisos” in Spanish. Towering over 100 feet tall, this step pyramid rises dramatically, with each tier representing a different stage in Edzna’s history, according to some researchers. A great staircase, studded with hieroglyphs, goes from the main plaza to the temple structure on the top of the pyramid. This temple is crowned with a combed roof that adds 19 more feet to it and is very reminiscent of the main pyramid at Tikal. This pyramid has 27 different rooms, and archaeologists believe that they were used for religious or governmental purposes. There are many other intricate details found on this pyramid, some of which were added during the last “renaissance” phase of the city corresponding to the rise of Chichén Itzá.

Another gem within Edzna’s archaeological treasures is the Temple of the Masks, located on the south side of the main plaza. The temple measures 90 feet long, 54 feet wide and 18 feet tall. It is adorned by two modeled stucco faces which are said to represent the sun god – K’inich Ahau – at sunrise and sunset. These masks are quite large, measuring 10 feet long by 3 feet high, and are flanked by various astronomical elements. Although formally called the Temple of the Masks, archaeologists are fairly certain that this building was dedicated to the worship of the sun.

A gigantic structure known as the Nohoch Na presides over the entire west side of the Grand Plaza. This huge platform base measures 443 feet in length, almost 100 feet wide, and some 30 feet in height. It has full-length stairways on both the east and west sides. There are two structures on the top of the platform separated by a passageway in the middle. Each structure has large rooms divided by a wall containing a dozen entryways. Researchers believe that this impressive structure seems to have served some sort of governmental function.

Reflecting the significance of the Mesoamerican ballgame, Edzná features a well-preserved ball court. This space, surrounded by tiered seating, measures 167 feet long by almost 17 feet wide. The remnants of a ballcourt ring are barely clinging to one of the walls inside the playing field. This court is located south of the Main Plaza in the heart of the civic-ceremonial part of the city.

Reflecting the significance of the Mesoamerican ballgame, Edzná features a well-preserved ball court. This space, surrounded by tiered seating, measures 167 feet long by almost 17 feet wide. The remnants of a ballcourt ring are barely clinging to one of the walls inside the playing field. This court is located south of the Main Plaza in the heart of the civic-ceremonial part of the city.

A sacbe, or stone road, leads out of the central plaza, going about a half mile to the northwest to a place called the Old Sorceress Group. This group contains 4 structures surrounding a smaller plaza. The structure on the west side of the plaza is a 9-tiered pyramid called “The Temple of the Witch” and stands almost 80 feet tall. The Old Sorceress Group was named by local Maya after an old legend involving the Moon Goddess who came down to earth in the form of an old woman to look after a young boy with extraordinary abilities. The “Sorceress” and “Witch” names stuck, and modern archaeologists refer to this group accordingly.

One of Edzná’s most remarkable features is its advanced hydraulic system, showcasing the Mayas’ engineering ingenuity. A network of canals and reservoirs, such as the Main Reservoir and the North Group Reservoirs, was strategically designed to manage water flow and storage. One mile south of the Main Plaza is what archaeologists have called “The Fortress.” The Fortress is a cluster of unrestored platform mounds surrounded by wetlands. Radiating outward from this ruined cluster are canals, reservoirs, embankments and  dams used to control the water allotted to farming areas. Researchers believe that without this sophisticated system Edzná never could have supplied the crops to feed its nearly 35,000 citizens at the city’s height. There is nothing quite like Edzná’s hydraulic system found anywhere in ancient Mexico.

dams used to control the water allotted to farming areas. Researchers believe that without this sophisticated system Edzná never could have supplied the crops to feed its nearly 35,000 citizens at the city’s height. There is nothing quite like Edzná’s hydraulic system found anywhere in ancient Mexico.

There are many other buildings at Edzná that make up the central part of the city and many more structures and other manmade features within the archaeological zone that have not yet been excavated or even identified. Only about 10% of the site has been thoroughly excavated and/or restored. It seems as if the city is waiting to tell the 21st Century the rest of its secrets, which are many, but for now they remain safe below the thick jungle undergrowth. With every passing month the story of Edzná becomes a bit clearer.

REFERENCES: INAH website