Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the late 1700s the Spanish Crown still held a monopoly over tobacco production in New Spain. Although the Spanish government prohibited the growth, harvesting and distribution of tobacco by private individuals, it was often difficult to police the more remote areas of colonial Mexico to look for renegade tobacco growers. The authorities created an official position of “tobacco guard” or “tobacco warden” to scour the remote parts of the countryside to enforce the Crown’s tobacco monopoly. Assigned to an obscure part of what is now the modern Mexican state of Veracruz, Diego Ruiz was one such official. While on one of his inspections in March of 1785, Ruiz stumbled across a gigantic ruined city in the hot jungle about 40 miles from the Gulf coast and about the same distance from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Madres. Ruiz made drawings of a large and unusually decorated pyramid, mostly covered in thick tropical vegetation, and published his accounts of the lost city in the Gaceta de Mexico, the oldest newspaper in the Americas published in Mexico City. In the article Ruiz stated that the local Totonac people called the abandoned city “Tajín,” which he claimed meant, “thunder” or “lightning bolt,” because according to local beliefs the 12 old thunderstorm gods still lived in the ruins. Although the ruins may have been visited by other Europeans before Ruiz, the tobacco inspector’s newspaper article marked the ancient site’s “rediscovery” by the outside world. Scholars, government officials and the curious began intense interest in this unusual place known today as El Tajín.

In the late 1700s the Spanish Crown still held a monopoly over tobacco production in New Spain. Although the Spanish government prohibited the growth, harvesting and distribution of tobacco by private individuals, it was often difficult to police the more remote areas of colonial Mexico to look for renegade tobacco growers. The authorities created an official position of “tobacco guard” or “tobacco warden” to scour the remote parts of the countryside to enforce the Crown’s tobacco monopoly. Assigned to an obscure part of what is now the modern Mexican state of Veracruz, Diego Ruiz was one such official. While on one of his inspections in March of 1785, Ruiz stumbled across a gigantic ruined city in the hot jungle about 40 miles from the Gulf coast and about the same distance from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Madres. Ruiz made drawings of a large and unusually decorated pyramid, mostly covered in thick tropical vegetation, and published his accounts of the lost city in the Gaceta de Mexico, the oldest newspaper in the Americas published in Mexico City. In the article Ruiz stated that the local Totonac people called the abandoned city “Tajín,” which he claimed meant, “thunder” or “lightning bolt,” because according to local beliefs the 12 old thunderstorm gods still lived in the ruins. Although the ruins may have been visited by other Europeans before Ruiz, the tobacco inspector’s newspaper article marked the ancient site’s “rediscovery” by the outside world. Scholars, government officials and the curious began intense interest in this unusual place known today as El Tajín.

In an ancient Aztec tribute or taxation record, El Tajín is seen on the map as being called Mictlán, or “place of the dead,” in English. They may have called the area by this name because by the time the Aztecs arrived in the late 15th Century the great city lay abandoned and had already been swallowed up by the jungle, with only a small Totonac village existing within the former boundaries of the great city. By around 1300 AD the city of El Tajín, its culture and political organization had crumbled after being dominant in the region for many centuries. Archaeologists theorize that people began settling the present-day site of the ruins around 100 AD during what scholars term the early Classic period of Mesoamerican civilization. Although researchers can  pinpoint a date of the city’s founding, give or take a century, they disagree as to who or what people built the city. Some say the Husatec, the Totnac or the Xapaneca, or possibly a combination of the three, but it is unclear who the builders or the rulers of the city were. The growth of the city seemed to parallel the growth of some of the larger urban centers to the west in the Mexican highlands such as Teotihuacan and some of the powerful Maya city-states to the east. During the height of El Tajín, from about 600 AD to 1200 AD we see many influences from the Maya region and the Mexican highlands, and vice versa. El Tajín appears to have been a major player in the Mesoamerican trade networks and also served as a large ceremonial or pilgrimage site for the Gulf Coast lowlands. Archaeologists see the influence the city had on its more powerful neighbor to the west, Teotihuacan, as evidenced by the various examples of El Tajín pottery styles unearthed in different parts of the city and the El Tajín artistic style found in murals and architecture at Teotihacan. If this did not indicate a direct political influence, it most likely indicated at least an indirect cultural one. Archaeological evidence suggests that immigrants or traders from El Tajín took up permanent residence in Teotihuacan in the area called La Ventanilla and what researchers now call the Merchants’ Barrio. Conversely, as a major regional power, some 50 ethnicities from as far away as Honduras lived within the boundaries of the city of El Tajín during its heyday from 600 AD to 1200 AD thus making it a true international city in ancient Mexico.

pinpoint a date of the city’s founding, give or take a century, they disagree as to who or what people built the city. Some say the Husatec, the Totnac or the Xapaneca, or possibly a combination of the three, but it is unclear who the builders or the rulers of the city were. The growth of the city seemed to parallel the growth of some of the larger urban centers to the west in the Mexican highlands such as Teotihuacan and some of the powerful Maya city-states to the east. During the height of El Tajín, from about 600 AD to 1200 AD we see many influences from the Maya region and the Mexican highlands, and vice versa. El Tajín appears to have been a major player in the Mesoamerican trade networks and also served as a large ceremonial or pilgrimage site for the Gulf Coast lowlands. Archaeologists see the influence the city had on its more powerful neighbor to the west, Teotihuacan, as evidenced by the various examples of El Tajín pottery styles unearthed in different parts of the city and the El Tajín artistic style found in murals and architecture at Teotihacan. If this did not indicate a direct political influence, it most likely indicated at least an indirect cultural one. Archaeological evidence suggests that immigrants or traders from El Tajín took up permanent residence in Teotihuacan in the area called La Ventanilla and what researchers now call the Merchants’ Barrio. Conversely, as a major regional power, some 50 ethnicities from as far away as Honduras lived within the boundaries of the city of El Tajín during its heyday from 600 AD to 1200 AD thus making it a true international city in ancient Mexico.

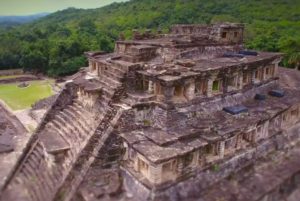

At its height, what did the city of El Tajín look like? The city and its suburbs covered over 2,600 acres and supported a population of around 25,000. In its early days El Tajín grew outward along north-south and east-west axes, but in the third phase of the city it shifted its growth to align with the orbit of Venus, the planet associated with the ever-present Mexican feathered serpent god known to the later Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl. The core area of the city includes over 200 mounds consisting of temples, elite residences, plazas, palaces, municipal buildings and some 20 ball courts, the largest amount of any ancient Mexican city. Archaeologists believe that El Tajín may have been the most important city in Mesoamerica for the cult of the ball game, and it may have been developed and elaborated at this city. For more detailed information about the Mesoamerican Ball Game please see Mexico Unexplained episode #53. The most dominant and important structure at El Tajín is the very unique-looking Pyramid of the Niches, which was the first building that caught the eye of Diego Ruiz, the royal tobacco inspector, in 1785. Built in several layers over several centuries, the Pyramid of the Niches, also called the Pyramid of Papantla or the Pyramid of the Seven Stories, stands 118 feet tall and was constructed in the familiar talud tablero style of many Mesoamerican temples. The pyramid’s seven stories are comprised of a rectangular feature called a tablero connected to a sloping talud to make up one story of the structure. The building is crowned with what architects call a “flying cornice.” The pyramid gets its most familiar name from the 365 box-like niches on its sides, one for each day of the year. Archaeologists debate the function of the niches. Some believe they represent caves and a connection to the underworld. Others believe that the niches once housed idols or some other ceremonial sculptures. At the height of El Tajín the Pyramid of the Niches was covered in plaster and painted a dark red color. Near the great pyramid are two large ball courts. The vertical walls of these courts are elaborately decorated in narrative bas-relief carvings, one of which depicts a scene in which a ball-player is about to be sacrificed. Art historians and architects note the special “scroll and volute” pattern carved along the ball courts which seems to be El Tajín’s signature design found on many buildings throughout the city and in other areas of ancient Mexico with El Tajín influence.

At its height, what did the city of El Tajín look like? The city and its suburbs covered over 2,600 acres and supported a population of around 25,000. In its early days El Tajín grew outward along north-south and east-west axes, but in the third phase of the city it shifted its growth to align with the orbit of Venus, the planet associated with the ever-present Mexican feathered serpent god known to the later Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl. The core area of the city includes over 200 mounds consisting of temples, elite residences, plazas, palaces, municipal buildings and some 20 ball courts, the largest amount of any ancient Mexican city. Archaeologists believe that El Tajín may have been the most important city in Mesoamerica for the cult of the ball game, and it may have been developed and elaborated at this city. For more detailed information about the Mesoamerican Ball Game please see Mexico Unexplained episode #53. The most dominant and important structure at El Tajín is the very unique-looking Pyramid of the Niches, which was the first building that caught the eye of Diego Ruiz, the royal tobacco inspector, in 1785. Built in several layers over several centuries, the Pyramid of the Niches, also called the Pyramid of Papantla or the Pyramid of the Seven Stories, stands 118 feet tall and was constructed in the familiar talud tablero style of many Mesoamerican temples. The pyramid’s seven stories are comprised of a rectangular feature called a tablero connected to a sloping talud to make up one story of the structure. The building is crowned with what architects call a “flying cornice.” The pyramid gets its most familiar name from the 365 box-like niches on its sides, one for each day of the year. Archaeologists debate the function of the niches. Some believe they represent caves and a connection to the underworld. Others believe that the niches once housed idols or some other ceremonial sculptures. At the height of El Tajín the Pyramid of the Niches was covered in plaster and painted a dark red color. Near the great pyramid are two large ball courts. The vertical walls of these courts are elaborately decorated in narrative bas-relief carvings, one of which depicts a scene in which a ball-player is about to be sacrificed. Art historians and architects note the special “scroll and volute” pattern carved along the ball courts which seems to be El Tajín’s signature design found on many buildings throughout the city and in other areas of ancient Mexico with El Tajín influence.

An immense acropolis comprising royal palaces and civic buildings stretching north-northwest from the older parts of the city is called Tajín Chico and was once considered a separate city by archaeologists before the jungle was cleared and no one knew just how big El Tajín proper actually was. This acropolis consists of an impressive structure called The Building of the Columns which served as the residence of the last rulers of El Tajín. In addition to the massive columns for which the building is so named, this residence also has detailed bas-relief carvings recording the life and times of one of the city’s last kings called Conejo Trece, or Thirteen Rabbit, in English. Tajín Chico also contains other edifices known only by their letters and numbers. While these buildings may have unremarkable names thanks to the archaeologists, the structures are not so unimpressive. Some of the best examples of Mesoamerican architecture are found at Tajín Chico, including some buildings with corbelled or Maya arches which show the city’s connection to the great Maya civilization hundreds of miles to the east. A remarkable feature of many of the buildings at El Tajín is the use of a special type of mortar similar to what the ancient Romans were using half a world away at approximately the same time called Pozzolanic cement. The builders of El Tajín combined silica- and aluminum-based sands into a cement mixture and combined it with small pebbles to create a special type of concrete. Much like today, builders poured the concrete into slabs and let it harden to incorporate it into structures. Many roofs of this concrete still exist in buildings at the archaeological site today.

An immense acropolis comprising royal palaces and civic buildings stretching north-northwest from the older parts of the city is called Tajín Chico and was once considered a separate city by archaeologists before the jungle was cleared and no one knew just how big El Tajín proper actually was. This acropolis consists of an impressive structure called The Building of the Columns which served as the residence of the last rulers of El Tajín. In addition to the massive columns for which the building is so named, this residence also has detailed bas-relief carvings recording the life and times of one of the city’s last kings called Conejo Trece, or Thirteen Rabbit, in English. Tajín Chico also contains other edifices known only by their letters and numbers. While these buildings may have unremarkable names thanks to the archaeologists, the structures are not so unimpressive. Some of the best examples of Mesoamerican architecture are found at Tajín Chico, including some buildings with corbelled or Maya arches which show the city’s connection to the great Maya civilization hundreds of miles to the east. A remarkable feature of many of the buildings at El Tajín is the use of a special type of mortar similar to what the ancient Romans were using half a world away at approximately the same time called Pozzolanic cement. The builders of El Tajín combined silica- and aluminum-based sands into a cement mixture and combined it with small pebbles to create a special type of concrete. Much like today, builders poured the concrete into slabs and let it harden to incorporate it into structures. Many roofs of this concrete still exist in buildings at the archaeological site today.

Dubbed the Arroyo Group by archaeologists for its proximity to three streams, this older part of the city consists of four identical buildings three of which are topped by temples surrounding a massive plaza. As El Tajín served as a trading hub and produced many desirable goods of its own, researchers theorize that this large public open space was the site of the city’s marketplace. Some remnants of the sticks and cloths that made up merchant stalls have been found in the great plaza along with effigies of the merchant god. Locally produced and sourced items such as cacao and pelts from jungle cats were offered alongside the typical pottery of El Tajín. These items were traded for essential foodstuffs and for luxury goods coming from as far away as Honduras and the modern-day American Southwest.

Dubbed the Arroyo Group by archaeologists for its proximity to three streams, this older part of the city consists of four identical buildings three of which are topped by temples surrounding a massive plaza. As El Tajín served as a trading hub and produced many desirable goods of its own, researchers theorize that this large public open space was the site of the city’s marketplace. Some remnants of the sticks and cloths that made up merchant stalls have been found in the great plaza along with effigies of the merchant god. Locally produced and sourced items such as cacao and pelts from jungle cats were offered alongside the typical pottery of El Tajín. These items were traded for essential foodstuffs and for luxury goods coming from as far away as Honduras and the modern-day American Southwest.

Civilizations rise and fall and El Tajíin was no exception to this rule. When the Mexican highland powerhouse of Teotihuacan fell, El Tajín still enjoyed dominance in its own region. When the Maya area started to collapse, however, this was a different matter and El Tajín felt a strain. As an important trading and ceremonial center in Ancient Mexico it could not survive the loss of the networks associated with the other highly-urbanized advanced civilizations in the area. Sometime in the early 13th Century what was left of the city suffered a great fire. Archaeologists theorize that nomadic raiders came from the north and sacked the city, setting it ablaze and destroying many public works of art in the process. After the great fire no one was left to care for the city and Mother Nature took its course, returning the area to the jungle it once was and leaving it to be discovered a few centuries later. Much more work needs to be done at this site. The fact that archaeologists are not even sure who built El Tajín is one of the many “problems” associated with this ancient city. With more and more interest shown in this great metropolis perhaps the many mysteries of El Tajíin will be solved one day soon.

REFERENCES

Longhena, Maria. Ancient Mexico: The History of te Maya, Aztecs, and Other Pre-Columbian Peoples. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2006.

Olmos, Ileana I. El Tajín: Preserving the Legacy of a Unique Pre-Columbian Architecture in Mesoamerica. Miami: University of Florida Press, 2009.

Weaver, Muriel Porter. The Aztecs, Maya and Their Predecessors. New York: Academic Press, 1981.