Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

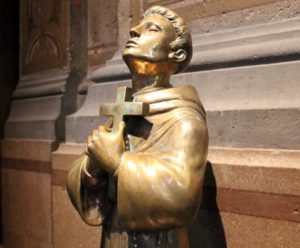

Dressed in black with her head covered in a dark lace cactus shawl, Antonia Martínez Fernández, made her way as part of the procession to Mexico City’s metropolitan cathedral. Antonia was almost 80 years old and was moving slowly, as was this long march of people to the religious heart of New Spain. The elderly Mexican woman was flanked by some of the most powerful people of the Spanish Empire in the New World, notably, the viceroy himself, the Marqués de Cerralvo, and the Archbishop of New Spain, Francisco Manso y Zúñiga. It was the morning of February 5, 1629. Antonia could not believe that she was part of such a grand spectacle, having left Spain for the New World as a girl some 70 years before. It was a jubilant but sad day for this woman whose son was being honored by a city for acts committed a continent and an ocean away some 2 decades before. In August of the previous year, the head of the Franciscans in Mexico, Francisco de la Cruz, had presented a bull of beatification signed by Pope Urban the Eighth, to various dignitaries in Mexico City: the archbishop, the viceroy and the members of the city council. The pope had honored the city by beatifying one of their own, the Mexico-City-born Felipe de las Casas known thenceforth as the Blessed Felipe de Jesús. Felipe’s mother, the elderly Antonia, had prayed the night before for the strength to participate in the solemn ceremonies and festivities to honor her son. She was too tired to take part in the masquerade held that night or to view the fireworks to be set off in her son’s honor. The officials of the city were proud of Antonia’s son and spent a great amount of resources to mark the first official feast day of the first person born in the New World, and the first Mexican, to be recognized by the pope in Rome to be put on the track for sainthood. Felipe de las Casas would eventually be canonized by Pope Pius the Ninth 233 years later in 1862.

Dressed in black with her head covered in a dark lace cactus shawl, Antonia Martínez Fernández, made her way as part of the procession to Mexico City’s metropolitan cathedral. Antonia was almost 80 years old and was moving slowly, as was this long march of people to the religious heart of New Spain. The elderly Mexican woman was flanked by some of the most powerful people of the Spanish Empire in the New World, notably, the viceroy himself, the Marqués de Cerralvo, and the Archbishop of New Spain, Francisco Manso y Zúñiga. It was the morning of February 5, 1629. Antonia could not believe that she was part of such a grand spectacle, having left Spain for the New World as a girl some 70 years before. It was a jubilant but sad day for this woman whose son was being honored by a city for acts committed a continent and an ocean away some 2 decades before. In August of the previous year, the head of the Franciscans in Mexico, Francisco de la Cruz, had presented a bull of beatification signed by Pope Urban the Eighth, to various dignitaries in Mexico City: the archbishop, the viceroy and the members of the city council. The pope had honored the city by beatifying one of their own, the Mexico-City-born Felipe de las Casas known thenceforth as the Blessed Felipe de Jesús. Felipe’s mother, the elderly Antonia, had prayed the night before for the strength to participate in the solemn ceremonies and festivities to honor her son. She was too tired to take part in the masquerade held that night or to view the fireworks to be set off in her son’s honor. The officials of the city were proud of Antonia’s son and spent a great amount of resources to mark the first official feast day of the first person born in the New World, and the first Mexican, to be recognized by the pope in Rome to be put on the track for sainthood. Felipe de las Casas would eventually be canonized by Pope Pius the Ninth 233 years later in 1862.

No one knows exactly where in Mexico City Felipe de las Casas was born or when, as no baptismal records exist. His year of birth is recognized as 1572. His parents were peninsulares, or those born in Spain, and both of them had immigrated to the New World less than a half century after the Conquest of the Aztecs and the fall of Tenochtitlán. It is unclear whether or not Felipe’s parents had come from moderate wealth or if they were members of the merchant class of New Spain. As a youth in colonial Mexico City, Felipe has been noted as having several different professions from silversmith apprentice to soldier. Much of his early life has been taken from secondhand accounts written many years after his death. The future  saint was said to have had a kind of “bad boy childhood” and has been described as restless or mischievous, and got into more than his share of trouble. Early church biographers struggled to piece together the saint’s early life which included very little “saintly” material. The young Felipe joined the Franciscans in Mexico City to bring a sense of order and discipline to his life but grew disenchanted with monastic life a few months after entering the friary. It was around the age of 17 or 18 in the year 1591 that Felipe’s father gave him some money to sail to Manila in the Spanish Philippines in hopes that his son would start a business there. Felipe’s early years in Asia are unclear and early biographers note that he took advantages of all the liberties that a bustling port city had to offer. By 1593, the listless Felipe de las Casas longed for a sense of discipline and perhaps some meaning to his life, so he decided to enter into religious life again.

saint was said to have had a kind of “bad boy childhood” and has been described as restless or mischievous, and got into more than his share of trouble. Early church biographers struggled to piece together the saint’s early life which included very little “saintly” material. The young Felipe joined the Franciscans in Mexico City to bring a sense of order and discipline to his life but grew disenchanted with monastic life a few months after entering the friary. It was around the age of 17 or 18 in the year 1591 that Felipe’s father gave him some money to sail to Manila in the Spanish Philippines in hopes that his son would start a business there. Felipe’s early years in Asia are unclear and early biographers note that he took advantages of all the liberties that a bustling port city had to offer. By 1593, the listless Felipe de las Casas longed for a sense of discipline and perhaps some meaning to his life, so he decided to enter into religious life again.

Documents show that Friar Vicente Valero, the master of novices at the Santa María de los Angeles Friary in Manila, admitted Felipe de las Casas on May 21, 1593. Felipe would have been 21 years old. He had chosen a particularly severe order, a group of “discalced” Franciscans who embraced a strictness in dress, work and prayer and who ministered among the poorest of the poor of Spain’s fledgling colony of Asia. This order of Franciscans was so regimented and thorough that King Phillip the Second of Spain put them in charge of evangelizing the Philippines in 1576 with wider aspirations for Asia. The Santa María friary where the young novice Felipe resided was the center for the Franciscans greater ambitions in Asia. It was from there that they sent out unsuccessful missionaries to China and it was there where they strategized and formulated their plans for expansion into Japan which began the same year Felipe entered the order. The Jesuits had already established a beachhead in the Japanese home islands and other Christian orders looked to this ancient country to expand into. The Japanese government, then headed by the regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi, had allowed a limited number of foreigners into the country and had tolerated the new practices of the Christians, although they were closely watched.

Felipe’s life at the Santa María de los Angeles friary in Manila was a quiet one and he was described as contemplative and hard-working. He showed great talent helping out in the infirmary, a later biographer would note. His life as a novice was ending and soon Felipe wanted to be a priest. Because the bishop’s seat in Manila was vacant, Felipe asked permission to return to Mexico City to take his vows. Permission was granted to him and in July of 1596 he left Manila bound for Acapulco on a Spanish galleon with other passengers and cargo. The ship, ironically, was named the San Felipe. Onboard ship was another discalced Franciscan named Juan de Pobre who kept a diary on the voyage. Much of what survives about what happened after Felipe de las Casas left the Philippines comes from Juan de Pobre’s writings. As soon as the galleon San Felipe left the South China Sea, it encountered a series of bad storms. Between August and October of 1596 the ship was tossed about, severely damaged and unable to navigate. By mid-October the ship found itself off the southern Japanese island of Shikoku and put into port at Urado. The officials on Shikoku did not know what to do with these foreigners who they suspected as being part of some sort of scout force of a Spanish invasion. For weeks the local Japanese officials squabbled with the passengers and crew of the San Felipe and the situation for those shipwrecked became worse. They decided to travel to Osaka to meet with the Spanish ambassador, another fellow discalced Franciscan by the name of Pedro Bautista who also had a small mission there. The young Mexican Felipe de las Casas undertook the journey to Osaka with Juan de Pobre and two merchants who were passengers on the ship. They wanted to obtain guarantees from the supreme leader of Japan that they could affect repairs on their ship and be let free to continue along their way to Mexico, with all of their cargo returned to them intact. When the four arrived in Osaka and met with the Spanish ambassador Pedro Bautista, Bautista assured them that the ruler of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, would put pressure on the local officials at Urado to let the San Felipe continue its journey. The Franciscan overestimated his influence at the Japanese court. Hideyoshi was already distrustful of foreigners. He had heard that the cargo of the galleon was worth over a million and a half pesos, and there were also arms onboard. The Spanish ambassador had no other allies in Japan to whom he could go for help. Not even his fellow Christians, the Jesuits, would assist in their cause because, as previously mentioned, they saw Franciscan encroachment in Japan as a threat to their total domination over Christianity in the region. With only 7 other Franciscans in the whole country, no allies and no money to bribe the local officials on the island of Shikoku, the young Mexican friar and his entourage were at the mercy of their Japanese captors. The situation soon escalated, the San Felipe was formally impounded by the Japanese government, and the castaways from the ship, along with the few Japanese Christian converts from the Franciscan mission, were jailed in early December of 1596. Hideyoshi, once sympathetic to the Franciscans, eventually ordered the execution of those jailed. The Japanese ruler explained, “Some years ago Fathers came to this realm preaching a diabolical law of alien kingdoms … introducing the customs of their lands, troubling hearts of the people, and destroying the administration of this kingdom.” After weeks of imprisonment, on January 3, 1597, guards cut off the left ears of the prisoners and paraded them around the city of Kyoto in wooden carts. The parading of the prisoners also took place in a handful of other Japanese cities. In addition to suffering through the extreme cold of winter, the prisoners suffered abuse at the hands of the Japanese public. Ordinary people came out to greet the parade with a volley of stones and angry citizens would shove weeds down the throats of the prisoners. The last stop on the grisly procession was the city of Nagasaki. On a hill outside of town on February 5, 1597 the prisoners were taken out of their wooden carts and promptly crucified. The young Mexican man who had lived a short life of piety in Asia was the first to die.

Felipe’s life at the Santa María de los Angeles friary in Manila was a quiet one and he was described as contemplative and hard-working. He showed great talent helping out in the infirmary, a later biographer would note. His life as a novice was ending and soon Felipe wanted to be a priest. Because the bishop’s seat in Manila was vacant, Felipe asked permission to return to Mexico City to take his vows. Permission was granted to him and in July of 1596 he left Manila bound for Acapulco on a Spanish galleon with other passengers and cargo. The ship, ironically, was named the San Felipe. Onboard ship was another discalced Franciscan named Juan de Pobre who kept a diary on the voyage. Much of what survives about what happened after Felipe de las Casas left the Philippines comes from Juan de Pobre’s writings. As soon as the galleon San Felipe left the South China Sea, it encountered a series of bad storms. Between August and October of 1596 the ship was tossed about, severely damaged and unable to navigate. By mid-October the ship found itself off the southern Japanese island of Shikoku and put into port at Urado. The officials on Shikoku did not know what to do with these foreigners who they suspected as being part of some sort of scout force of a Spanish invasion. For weeks the local Japanese officials squabbled with the passengers and crew of the San Felipe and the situation for those shipwrecked became worse. They decided to travel to Osaka to meet with the Spanish ambassador, another fellow discalced Franciscan by the name of Pedro Bautista who also had a small mission there. The young Mexican Felipe de las Casas undertook the journey to Osaka with Juan de Pobre and two merchants who were passengers on the ship. They wanted to obtain guarantees from the supreme leader of Japan that they could affect repairs on their ship and be let free to continue along their way to Mexico, with all of their cargo returned to them intact. When the four arrived in Osaka and met with the Spanish ambassador Pedro Bautista, Bautista assured them that the ruler of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, would put pressure on the local officials at Urado to let the San Felipe continue its journey. The Franciscan overestimated his influence at the Japanese court. Hideyoshi was already distrustful of foreigners. He had heard that the cargo of the galleon was worth over a million and a half pesos, and there were also arms onboard. The Spanish ambassador had no other allies in Japan to whom he could go for help. Not even his fellow Christians, the Jesuits, would assist in their cause because, as previously mentioned, they saw Franciscan encroachment in Japan as a threat to their total domination over Christianity in the region. With only 7 other Franciscans in the whole country, no allies and no money to bribe the local officials on the island of Shikoku, the young Mexican friar and his entourage were at the mercy of their Japanese captors. The situation soon escalated, the San Felipe was formally impounded by the Japanese government, and the castaways from the ship, along with the few Japanese Christian converts from the Franciscan mission, were jailed in early December of 1596. Hideyoshi, once sympathetic to the Franciscans, eventually ordered the execution of those jailed. The Japanese ruler explained, “Some years ago Fathers came to this realm preaching a diabolical law of alien kingdoms … introducing the customs of their lands, troubling hearts of the people, and destroying the administration of this kingdom.” After weeks of imprisonment, on January 3, 1597, guards cut off the left ears of the prisoners and paraded them around the city of Kyoto in wooden carts. The parading of the prisoners also took place in a handful of other Japanese cities. In addition to suffering through the extreme cold of winter, the prisoners suffered abuse at the hands of the Japanese public. Ordinary people came out to greet the parade with a volley of stones and angry citizens would shove weeds down the throats of the prisoners. The last stop on the grisly procession was the city of Nagasaki. On a hill outside of town on February 5, 1597 the prisoners were taken out of their wooden carts and promptly crucified. The young Mexican man who had lived a short life of piety in Asia was the first to die.

News of the martyrs soon spread outside Nagasaki. Christian converts and a few remaining Spaniards and Portuguese had heard of the execution and had visited the site soon after. As is standard in stories about the saints and martyrs of the Church, the bodies of those crucified were untouched by scavengers and showed no signs of decomposition. Christian subjects throughout the Spanish Empire became outraged when hearing the news of what had happened in Japan. The Franciscans used the outrage to encourage devotion to the slain Christians and proposed martyr status for Felipe de las Casas and his companions. They sent a surviving Franciscan who had eluded Hideyoshi’s capture, a Portuguese named Marcelo de Ribadeneira, to Rome by way of Mexico City to plead the case of martyrdom to the pope. Ribadeneira carried with him personal effects of the martyrs to be used as relics of devotion to further the cause of recognition. While there was initial interest in the case for martyrdom for Felipe and a growing devotion to him in Mexico City, by the time Ribadeneira left Mexico, interest in the home-grown holy man waned, and people returned to their traditional devotions to European saints and manifestations of the Virgin Mary that had proven track records of miracles and intercessions. It took a great deal of lobbying in Rome to get Felipe recognized and later beatified, and the elites of Mexico City in the early 17th Century used the fact that their town had produced a man on his way to becoming a saint to foster a sense of pride, thus elevating their city’s status within the Spanish Empire. The local people, though, had a hard time accepting the young Mexican martyr as a saint they could rely on even though Felipe de las Casas, renamed Felipe de Jesús, was one of their own. With time and a large PR campaign in the early days, this martyred man who died so far away from Mexico became an important part of the Catholic pantheon and Mexican religious life and has thousands of devoted followers centuries after his death.

News of the martyrs soon spread outside Nagasaki. Christian converts and a few remaining Spaniards and Portuguese had heard of the execution and had visited the site soon after. As is standard in stories about the saints and martyrs of the Church, the bodies of those crucified were untouched by scavengers and showed no signs of decomposition. Christian subjects throughout the Spanish Empire became outraged when hearing the news of what had happened in Japan. The Franciscans used the outrage to encourage devotion to the slain Christians and proposed martyr status for Felipe de las Casas and his companions. They sent a surviving Franciscan who had eluded Hideyoshi’s capture, a Portuguese named Marcelo de Ribadeneira, to Rome by way of Mexico City to plead the case of martyrdom to the pope. Ribadeneira carried with him personal effects of the martyrs to be used as relics of devotion to further the cause of recognition. While there was initial interest in the case for martyrdom for Felipe and a growing devotion to him in Mexico City, by the time Ribadeneira left Mexico, interest in the home-grown holy man waned, and people returned to their traditional devotions to European saints and manifestations of the Virgin Mary that had proven track records of miracles and intercessions. It took a great deal of lobbying in Rome to get Felipe recognized and later beatified, and the elites of Mexico City in the early 17th Century used the fact that their town had produced a man on his way to becoming a saint to foster a sense of pride, thus elevating their city’s status within the Spanish Empire. The local people, though, had a hard time accepting the young Mexican martyr as a saint they could rely on even though Felipe de las Casas, renamed Felipe de Jesús, was one of their own. With time and a large PR campaign in the early days, this martyred man who died so far away from Mexico became an important part of the Catholic pantheon and Mexican religious life and has thousands of devoted followers centuries after his death.

REFERENCES

Conover, Cornelius and Cory Conover. “Saintly Biography and the Cult of San Felipe de Jesus in Mexico City, 1597-1697.” In The Americas, vol. 67, no. 4 (April 2011), pp. 441-466.