Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

It was a warm day in May in the year 1519. Messengers sent to the coast had returned to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. They entered the imperial palace of Montezuma and supplicated themselves before the great emperor, who ruled over more than a million people and whose empire was the largest ever seen in ancient Mexico. The Aztec ruler had sent the messengers to the territory of the Totonacs, an Aztec tributary state on the gulf coast, after hearing strange stories of men arriving on floating mountains from far across the sea. The first messenger spoke, his voice trembling, describing what they had seen:

It was a warm day in May in the year 1519. Messengers sent to the coast had returned to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. They entered the imperial palace of Montezuma and supplicated themselves before the great emperor, who ruled over more than a million people and whose empire was the largest ever seen in ancient Mexico. The Aztec ruler had sent the messengers to the territory of the Totonacs, an Aztec tributary state on the gulf coast, after hearing strange stories of men arriving on floating mountains from far across the sea. The first messenger spoke, his voice trembling, describing what they had seen:

“Their trappings and arms are all made of iron. They dress in iron and wear iron casques on their heads. Their swords are iron; their bows are iron; their shields are iron; their spears are iron. Their deer carries them on their backs wherever they wish to go. These deer, our lord, are as tall as the roof of a house.

“The strangers’ bodies are completely covered so that only their faces can be seen. Their skin is white as if it were made of lime. They have yellow hair though some of them have black. Their beards are long and yellow, and their mustaches are also yellow. Their hair is curly with very fine strands.

“As for their food it is like Mexica food. It is large and white and not heavy. It is something like straw, but with the taste of a cornstalk, of the pith of cornstalk. It is a little sweet as if it were flavored with honey; it tastes of honey, it is sweet tasting food.

“Their dogs are enormous with flat ears and long dangling tongues. The color of their eyes is a burning yellow. Their eyes flash fire and shoot off sparks. Their bellies are hollow. Their flanks long and narrow. They are tireless and very powerful. They bound here and there panting with their tongues hanging out and they are spotted like an ocelot.”

Another messenger attempted to describe a Spanish cannon.

“A thing like a bottle of stone comes out of its entrails: it comes out shooting sparks and raining fire. The smoke that comes out with it has a pestilent odor, like that of rotten mud. This odor penetrates even to the brain and causes the greatest discomfort. If the cannon is aimed against a mountain, the mountains splits and cracks open. If it’s aimed against tree, it shatters the tree into splinters. This is the most unnatural sight as if the tree had exploded from within.”

The Aztec emperor stood there with many thoughts on his mind. Who were these people and how would he handle them?

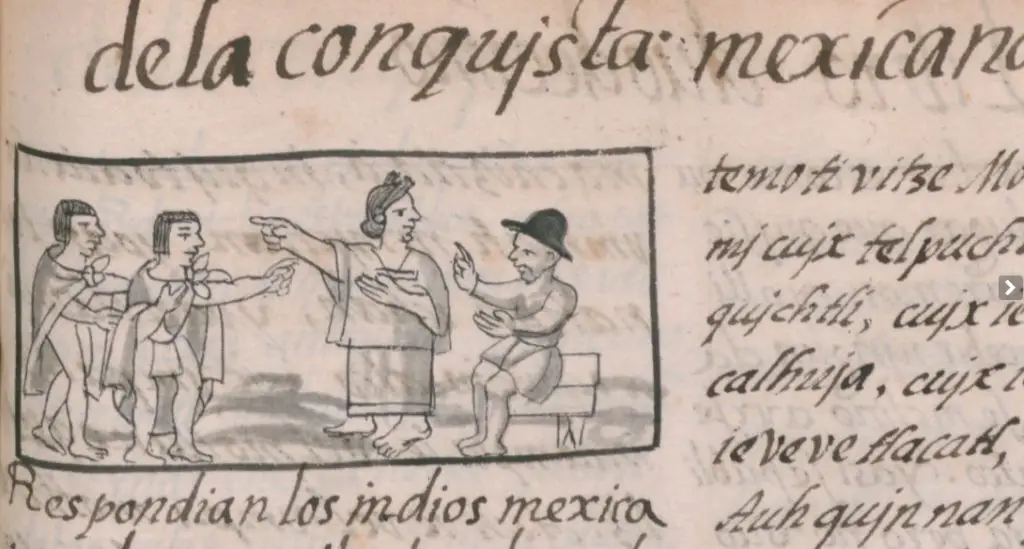

The previous scene with direct quotes was taken from the Florentine Codex, a multi-volume document created between 1545 and 1590 by Franciscan Friar Bernardino de Sahagún with the help of an untold number of native Mexican scribes and illustrators. In the 2,400 pages of this work, known in Spanish as La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, or in English, The Universal History of the Things of New Spain, Sahagún detailed much of the latter history of the Aztec Empire and is considered the first ethnographer of the Americas. The enormous work was written both in Spanish and in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and the lingua franca, or most commonly spoken second language, used throughout Mexico at the time. In the twelfth book of the Florentine Codex, Sahagún tells of the conquest of the Aztecs from an indigenous point of view. In the early part of the compilation of the materials for this work, in the mid-1540s and early 1550s, the Franciscan interviewed people who were alive and had witnessed the events he wrote about.

The previous scene with direct quotes was taken from the Florentine Codex, a multi-volume document created between 1545 and 1590 by Franciscan Friar Bernardino de Sahagún with the help of an untold number of native Mexican scribes and illustrators. In the 2,400 pages of this work, known in Spanish as La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, or in English, The Universal History of the Things of New Spain, Sahagún detailed much of the latter history of the Aztec Empire and is considered the first ethnographer of the Americas. The enormous work was written both in Spanish and in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and the lingua franca, or most commonly spoken second language, used throughout Mexico at the time. In the twelfth book of the Florentine Codex, Sahagún tells of the conquest of the Aztecs from an indigenous point of view. In the early part of the compilation of the materials for this work, in the mid-1540s and early 1550s, the Franciscan interviewed people who were alive and had witnessed the events he wrote about.

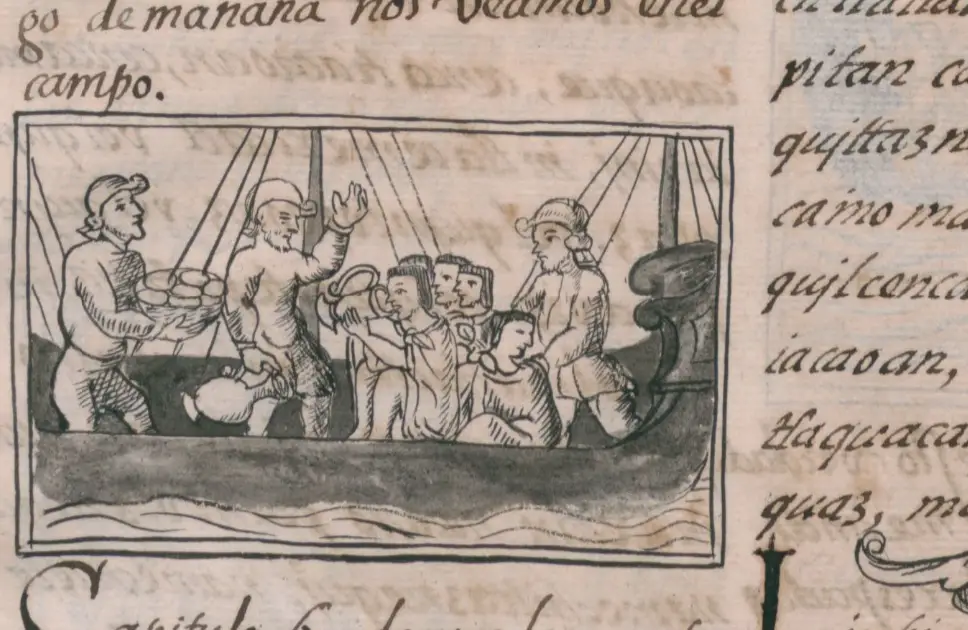

Cortés arrived on the coast of the modern Mexican state of Veracruz in April of 1519. After leaving Cuba, he made his first landfall in the Yucatán and skirted the coast until he decided on a more permanent anchorage. Cortés’s expedition consisted of 11 ships carrying about 630 men which included less than 50 professional soldiers, some trained in the crossbow and some trained in firearms. The Cortés contingent also included, a doctor, several carpenters, at least eight women, a few hundred native Arawak people from Cuba and some Africans, both freedmen and slaves. When Cortés left Cuba, he clearly did not set out to conquer an empire as so few of his 630 people were considered “soldiers.” As already mentioned, soon after he arrived on the coast, in Totonac territory, word of Cortes’ arrival quickly made it to central Mexico and the capital city of the Aztecs, Tenochtitlan.

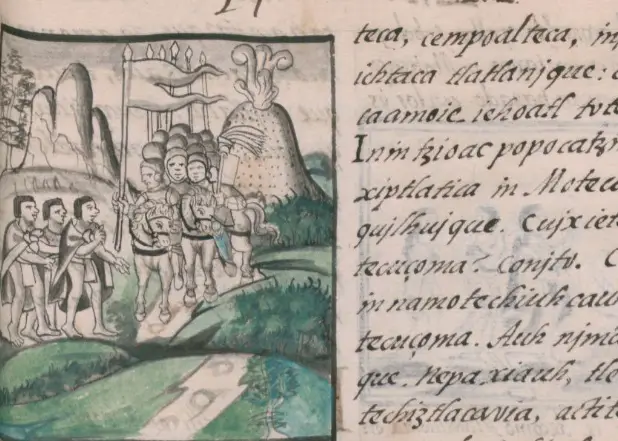

After the first set of messengers returned to the Aztec capital, Montezuma sent a small group of what the Spanish called “magicians and sorcerers” to try to scare the newcomers away. This small delegation was probably comprised of priests and holy men who were well known in the Empire for their powers of divination and their supernatural abilities. They arrived at the newly built Spanish city of Veracruz and no display of Mexican “sorcery” would impress Cortés’ contingent. Nothing they could do would turn away the invaders. When the holy men returned to the Aztec capital, one of them proclaimed, “Our lord, we are no match for them! We are mere nothings!” This caused Montezuma to change his strategy. The emperor thought that if he gave the strange men what they wanted, they would leave his people alone. More delegations were sent to Cortés with more gifts. Soon, word made it to the capital that the newcomers were marching overland to Tenochtitlan. Montezuma felt he was left with no other course of action but to welcome them with open arms as honored guests.

After the first set of messengers returned to the Aztec capital, Montezuma sent a small group of what the Spanish called “magicians and sorcerers” to try to scare the newcomers away. This small delegation was probably comprised of priests and holy men who were well known in the Empire for their powers of divination and their supernatural abilities. They arrived at the newly built Spanish city of Veracruz and no display of Mexican “sorcery” would impress Cortés’ contingent. Nothing they could do would turn away the invaders. When the holy men returned to the Aztec capital, one of them proclaimed, “Our lord, we are no match for them! We are mere nothings!” This caused Montezuma to change his strategy. The emperor thought that if he gave the strange men what they wanted, they would leave his people alone. More delegations were sent to Cortés with more gifts. Soon, word made it to the capital that the newcomers were marching overland to Tenochtitlan. Montezuma felt he was left with no other course of action but to welcome them with open arms as honored guests.

History seems to be a bit cloudy regarding what the Aztecs really thought of Cortés and his followers. For many years the standard history stated that Montezuma and the Aztecs thought the conquistador was a returning god. This presupposes a few things. This assumes an almost inferior attitude toward the Aztecs in that they were unable to tell mere mortals from gods. As stated in the Florentine Codex, the Aztec messengers reported on all aspects of the strange group, including some very human characteristics. It was most likely that the Aztecs did not see the Spaniards as “gods.” There has been a persistent claim in historical literature that Montezuma “mistook” Cortés as the Mesoamerican god Quetzalcoatl who had promised to return from the east to reclaim some sort of earthly throne. One of the phrases often cited as proof of this is something that Montezuma said to the conquistador in their initial meeting: “I have been saving the throne for you.” Upon further investigation, this phrase was uttered to any important foreign guest arriving at Tenochtitlan to be received at the imperial palace whether it was a visiting member of the Tarascan royal family or a newly subjugated king. It was a phrase of courtesy along the lines of “Mi casa es su casa,” or “My house is your house” in modern-day Mexico. The whole idea of Cortés being mistaken for the returning god Quetzalcoatl only started to appear in writings generations after the Conquest, and some scholars re-examining this “First Contact” history believe that the story of the Cortés-Quetzalcoatl mix-up was created by the Spanish to somehow legitimize the Conquest in the eyes of the thousands of indigenous living under Spanish rule in colonial New Spain. The Spanish, you see, were destined to rule Mexico as per the Aztec prophesy, with the return of the “feathered serpent” which had morphed into “the bearded serpent.” The only problem is, there is no evidence for this mythical case of mistaken identity dating from the time of the Conquest. Never once in the writings of Cortés or in the writings of his companions is the god story mentioned. Indigenous scribes writing in Nahuatl at the time did not mention this story, either. For more information about Quetzalcoatl, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 100: https://mexicounexplained.com/quetzalcoatl-man-myth-god/

Along the way to the capital city, Cortés did battle with various indigenous groups and also made several allies of kingdoms and cities that were tired of living life as subjects of the Aztec Empire. All the while, Montezuma kept sending emissaries with gifts to the advancing party. Cortés was presented with gold and elaborate feather work, and other objects of great value. In the Florentine Codex, this gift-giving was described thus by native witnesses:

Along the way to the capital city, Cortés did battle with various indigenous groups and also made several allies of kingdoms and cities that were tired of living life as subjects of the Aztec Empire. All the while, Montezuma kept sending emissaries with gifts to the advancing party. Cortés was presented with gold and elaborate feather work, and other objects of great value. In the Florentine Codex, this gift-giving was described thus by native witnesses:

“And when they were given these presents, the Spaniards burst into smiles, their eyes shone with pleasure; they were delighted by them. They picked up the gold and passed it through their fingers like monkeys; they seemed to be transported by joy, as if their hearts were illumined and made new.”

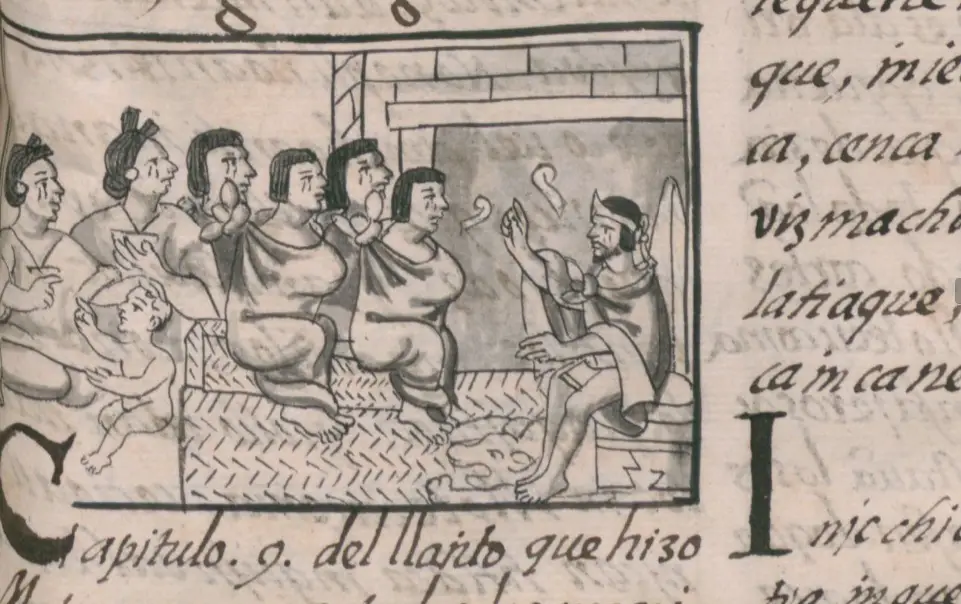

The Spanish party finally made it to Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519. By that time the population of the city was filled with anxiety and dread, fearing what these foreigners would bring to their peaceable capital. There were several bad omens that had occurred heralding this event which only added to the free-floating tension felt in the heart of the Aztec Empire. What started off as a group of a little over 600 people on the coast had grown into the thousands. Cortés approached the city from the south. As the Aztec capital was in the middle of Lake Texcoco, the conquistadors crossed the southern causeway to enter the city at a place called Xoloco. The exact meeting point of Montezuma and Cortés did not occur at the imperial palace as some sources state, but in a part of the capital city called Huitzillan located in present-day Mexico City on Avenida San Antonio Abad. Montezuma, decked out in his imperial finery was waiting for the Spaniard at the designated meeting point along with princes from his immediate family, also dressed in appropriate finery. Along with the princes of Tenochtitlan were nobles from surrounding kingdoms and allied states. Before being presented to the emperor, the newcomers were greeted with trays and baskets overflowing with beautiful flowers, as well as garlands of flowers and necklaces of gold.

Montezuma prepared an elaborate speech of welcome which was somewhat difficult for Cortés’ official translator, La Malinche, to properly put into words in Spanish. The emperor was using a flowery and poetic type of language reserved for the highest members of society. The Malinche translated as best she could. Montezuma’s speech was overflowing with hospitality and included the “we are saving the throne for you” phrase previously mentioned. The emperor knew of the danger present and was trying his best to be as diplomatic as possible until he could properly ascertain the Spaniards’ true intentions for himself. Cortés’ response was not scripted at all and to native witnesses was not in the least bit eloquent. According to the Florentine Codex, the conquistador said this to La Malinche:

“Tell Montezuma that we are friends. There is nothing to fear. We have wanted to see him for a long time, and now we have seen his face and heard his words. Tell him that we love him well and that our hearts are contented.”

“Tell Montezuma that we are friends. There is nothing to fear. We have wanted to see him for a long time, and now we have seen his face and heard his words. Tell him that we love him well and that our hearts are contented.”

He then turned to Montezuma directly and said, “We have come to your house in Mexico as friends. There is nothing to fear.”

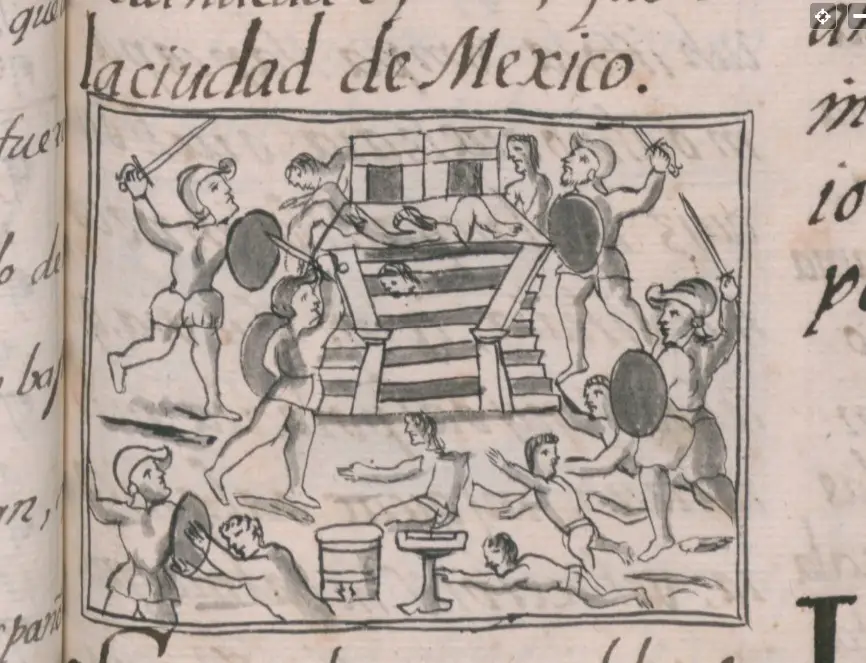

The friendship would not last, and after a brief period of hospitality, the Spanish turned on their generous hosts. The population of the capital city reacted with utter astonishment. It would take a few years, but the mighty empire of the Aztecs would soon come to an end. And the rest, as they say, is history.

REFERNCES:

Leon Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. New York: Beacon Press, 1963. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3Qsizue