Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

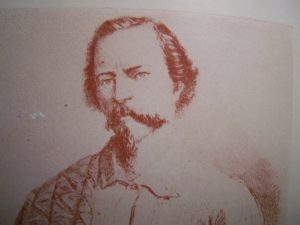

On May 5th 1817 in the elegant home of the French dowager Marquise de Sariac, a boy was born. He was christened Gabriel-Marie-Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon, later shortened to Gaston. He would inherit the title of “count” from his father, who hailed from one of the most ancient noble families of the city of Avignon in the region of Provence in southern France. Soon after he was born, Gaston’s mother died, and his father abandoned him to the household of his grandmother the marquise. While Gaston was well taken care of on the estate of his grandmother, the lack of a father in his life caused the young Gaston to act out. His grandmother’s servants found it increasingly difficult to handle his violent outbursts, his indomitable spirit and his general obstinance. At the age of seven, Gaston beat his tutor and claimed the right to rule the household. This enfant terrible was called “The Wolf Cub” by the servants who begged the marquise to take more drastic measures with the boy. Madame de Sariac wrote to Gaston’s father to take him, but he would not. It was then agreed that “The Wolf Cub” would be sent off to a Jesuit college in Freiburg, Germany, where many noble families of Germany and France sent their troublesome children. As one of Gaston’s biographers would account, “After several days of observation, these scientists of the soul decided that this young wolf had the makings of a hero. They took care not to irritate him, and by the influence of reason, emulation and, above all, insistence upon the point of honor, won from him what they could never have obtained by compulsion. Two years later, the “wolf cub” was the eagle of the college.” He spent nine years there.

On May 5th 1817 in the elegant home of the French dowager Marquise de Sariac, a boy was born. He was christened Gabriel-Marie-Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon, later shortened to Gaston. He would inherit the title of “count” from his father, who hailed from one of the most ancient noble families of the city of Avignon in the region of Provence in southern France. Soon after he was born, Gaston’s mother died, and his father abandoned him to the household of his grandmother the marquise. While Gaston was well taken care of on the estate of his grandmother, the lack of a father in his life caused the young Gaston to act out. His grandmother’s servants found it increasingly difficult to handle his violent outbursts, his indomitable spirit and his general obstinance. At the age of seven, Gaston beat his tutor and claimed the right to rule the household. This enfant terrible was called “The Wolf Cub” by the servants who begged the marquise to take more drastic measures with the boy. Madame de Sariac wrote to Gaston’s father to take him, but he would not. It was then agreed that “The Wolf Cub” would be sent off to a Jesuit college in Freiburg, Germany, where many noble families of Germany and France sent their troublesome children. As one of Gaston’s biographers would account, “After several days of observation, these scientists of the soul decided that this young wolf had the makings of a hero. They took care not to irritate him, and by the influence of reason, emulation and, above all, insistence upon the point of honor, won from him what they could never have obtained by compulsion. Two years later, the “wolf cub” was the eagle of the college.” He spent nine years there.

When Gaston was 18 he inherited 300,000 Francs from his mother’s estate and immediately went to Paris to live the high life of a young gentleman in this cosmopolitan capital. In addition to his Paris apartment, he owned a luxurious houseboat on the Seine, which was a novelty at the time. He rode in a coach driven by black horses harnessed in silver and passed his days in the Parisian cafés discussing politics and entertainment. After 10 years of living as an idler, Gaston grew quite restless and wearied of Paris. He was ready for his first adventure.

When Gaston was 18 he inherited 300,000 Francs from his mother’s estate and immediately went to Paris to live the high life of a young gentleman in this cosmopolitan capital. In addition to his Paris apartment, he owned a luxurious houseboat on the Seine, which was a novelty at the time. He rode in a coach driven by black horses harnessed in silver and passed his days in the Parisian cafés discussing politics and entertainment. After 10 years of living as an idler, Gaston grew quite restless and wearied of Paris. He was ready for his first adventure.

At the time Marshall Bugeaud had just conquered Algiers and the French government was encouraging French colonization of Algeria. Gaston saw an excellent opportunity for a new life in a new country, someplace that would test his mettle and fortitude. He moved to North Africa and used what was left of his fortune to buy land in the Mitidja region, but found that he had no knack for agriculture and very little patience for the French military governors of the new colony, whom he described as tyrannical. By 1848, he sold his Algerian holdings at a considerable loss and returned to Avignon to live with his grandmother at her comfortable estate. It was there where he regrouped and planned his next move.

It was not long before he reestablished himself in France that Gaston became interested in the stories he had heard coming from California. The former Mexican backwater was newly acquired by the United States and gold fever had drawn people there from all over the world. San Francisco – once known as the sleepy Spanish outpost of Yerba Buena – had ballooned in size as a result. Gaston, nearly penniless, gathered together enough money for a passage to California and to buy a mechanical dredging machine, and set out for the New World. He wrote extensively in his diaries and letters to his friends back home about the harrowing journey from France to Panama, and then how he and other fortune-seekers made the dangerous jungle crossing through Panama to the Pacific, at which point they boarded another ship for San Francisco. The trip took months, but the eager “wolf cub” was certain he would make a new life for himself in the goldfields of the Sierra Nevadas.

It was not long before he reestablished himself in France that Gaston became interested in the stories he had heard coming from California. The former Mexican backwater was newly acquired by the United States and gold fever had drawn people there from all over the world. San Francisco – once known as the sleepy Spanish outpost of Yerba Buena – had ballooned in size as a result. Gaston, nearly penniless, gathered together enough money for a passage to California and to buy a mechanical dredging machine, and set out for the New World. He wrote extensively in his diaries and letters to his friends back home about the harrowing journey from France to Panama, and then how he and other fortune-seekers made the dangerous jungle crossing through Panama to the Pacific, at which point they boarded another ship for San Francisco. The trip took months, but the eager “wolf cub” was certain he would make a new life for himself in the goldfields of the Sierra Nevadas.

Working a gold claim was much more difficult that the young count had expected. He earned enough to keep a roof over his head in the part of San Francisco known as “The French Refuge” but had grown bored of the life of earning a simple living as a gold prospector. While in San Francisco he became friends with many other Frenchmen living out the same dream he was. Among them was the Marquis Charles de Pindray who had a similar  background as Gaston. The Marquis was from an old noble family and had a troubled childhood. He was also taken in by the Jesuits who gave him a formal education and who rounded out his rough edges. The Marquis de Pindray came to America with the intentions to live large and to make a fortune, much like Gaston. It was Pindray who put into Gaston’s head the idea of leaving California and heading for a richer, more untamed land called Sonora in northern Mexico.

background as Gaston. The Marquis was from an old noble family and had a troubled childhood. He was also taken in by the Jesuits who gave him a formal education and who rounded out his rough edges. The Marquis de Pindray came to America with the intentions to live large and to make a fortune, much like Gaston. It was Pindray who put into Gaston’s head the idea of leaving California and heading for a richer, more untamed land called Sonora in northern Mexico.

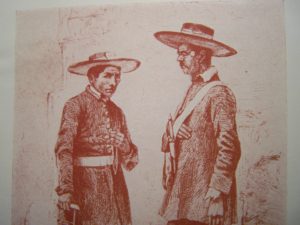

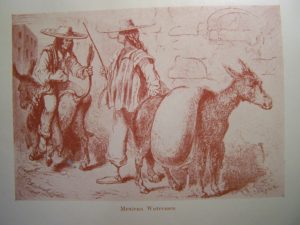

At the time, Mexico was completely incapable of ruling its northern provinces. Apache and Yaqui Indian raids hampered permanent settlement and made commerce and travel difficult. The central government in Mexico City knew it had to do something to pacify the northern part of the country or possibly risk more territorial loss to the United States whose expansion into almost 50% of Mexico after the Mexican War was still on the minds of the Mexicans. Knowing that San Francisco was home to a large number of adventurers and discouraged prospectors at the end of their resources, the Mexican government encouraged – through their consul named Del Valle –  the formation of an expeditionary force to go to Sonora to tame the land and open old mines. The French consul, a man named Patrice Dillon, was behind this idea fully, because he thought it would rid San Francisco of certain rambunctious Frenchmen who were a constant thorn in the side of the French consulate in the city. Dillon approached the Marquis de Pindray with the offer to lead the Sonoran adventure. He accepted. Count Gaston, who had been away in Los Angeles on business at the time, joined the expedition later.

the formation of an expeditionary force to go to Sonora to tame the land and open old mines. The French consul, a man named Patrice Dillon, was behind this idea fully, because he thought it would rid San Francisco of certain rambunctious Frenchmen who were a constant thorn in the side of the French consulate in the city. Dillon approached the Marquis de Pindray with the offer to lead the Sonoran adventure. He accepted. Count Gaston, who had been away in Los Angeles on business at the time, joined the expedition later.

Pindray, Gaston and dozens of other Frenchmen, along with some Americans and other foreigners, established themselves in the town of Cocóspera about 50 miles south of modern-day Nogales. The town consisted of an old Spanish mission, a rancho and several habitations, but it was not well-defended and was constantly raided by Indians and desperadoes. The Marquis de Pindray was ultimately killed during one of the raids and Gaston was made leader of what was left of the expeditionary party. The remaining force, decimated, eventually withdrew and returned to San Francisco. There, Count Gaston had another plan simmering.

After securing the necessary funds, on May 25, 1852 Gaston left San Francisco for Mexico City, a detailed plan in hands. When he arrived at the capital, the French count met with the president, Mariano Arista. The president approved of his plan, gave Gaston sixty thousand piasters and assured him of his complete support of his new project to colonize and pacify Sonora. Of prime interest of the Mexican president was the reopening of  the mines, as the Mexican treasury had nearly been depleted. Arista also wanted some of the money from the mines for himself as he had a feeling that his own days were numbered as the leader of Mexico.

the mines, as the Mexican treasury had nearly been depleted. Arista also wanted some of the money from the mines for himself as he had a feeling that his own days were numbered as the leader of Mexico.

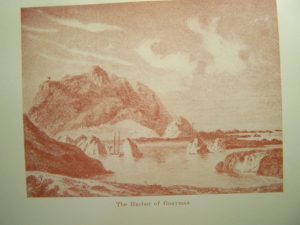

Later that year Gaston landed in Guaymas with his contingent of men and was met by 200 soldiers of a Mexican regiment that had been pledged to help him establish order in Sonora. The local governor of the state of Sonora, General Blanco, who was at odds with the central government in Mexico City did not like this foreign intrusion into his territory. He would not yield the capital city of Hermosillo to Count Gaston’s forces and a battle ensued. The general was defeated, and the foreign expeditionary force held Hermosillo. The victory was short lived, as the forces loyal to the general retook the city and caused the invaders to march back to the sea. After spending a brief time recovering from an illness in Mazatlán, Gaston returned to San Francisco to regroup again. In a letter back to France, Gaston wrote:

“No, I have not abandoned hope of getting the best of it in the struggle with ill luck that I have waged since leaving the cradle; Sisyphus rolling his eternal rock, Jacob wrestling every night with a phantom – these are images from the lives of men whose careers resemble mine. No, I have not given up. When I found myself abandoned by my men, when I was at Death’s door, I had only one thought – to win back health, strength and mental force and return to Sonora.”

In his next attempt he knew he needed some serious backing. He had a grand plan for Sonora that went beyond his personal profiteering. From his days in colonial Algeria, Gaston had become closely connected with the family of Orléans and had a continuing correspondence with the Duke of Aumale. During a brief visit to San Francisco, Gaston became friends with François de Orléans, Prince of Joinville, the current Duke of Orléans’ third son who was married to the beautiful Princess Francisca de Bragança, the daughter of the Emperor of Brazil. With proper backing, Gaston wished for an independent Sonora ruled by the Prince of Joinville, a colonial paradise that would attract industrious immigrants from all parts of the world and whose military, and royal court, would be decidedly French. The old mines would be reopened and the irrigation programs like the ones the French used in Algeria would make the deserts of Sonora agriculturally productive. The Principality of Sonora would be ruled independently of France, a hereditary monarchy headed by the male heir of the House of Orléans. The nation of Mexico, aware of Count Gaston’s scheme, had other plans for Sonora.

In his next attempt he knew he needed some serious backing. He had a grand plan for Sonora that went beyond his personal profiteering. From his days in colonial Algeria, Gaston had become closely connected with the family of Orléans and had a continuing correspondence with the Duke of Aumale. During a brief visit to San Francisco, Gaston became friends with François de Orléans, Prince of Joinville, the current Duke of Orléans’ third son who was married to the beautiful Princess Francisca de Bragança, the daughter of the Emperor of Brazil. With proper backing, Gaston wished for an independent Sonora ruled by the Prince of Joinville, a colonial paradise that would attract industrious immigrants from all parts of the world and whose military, and royal court, would be decidedly French. The old mines would be reopened and the irrigation programs like the ones the French used in Algeria would make the deserts of Sonora agriculturally productive. The Principality of Sonora would be ruled independently of France, a hereditary monarchy headed by the male heir of the House of Orléans. The nation of Mexico, aware of Count Gaston’s scheme, had other plans for Sonora.

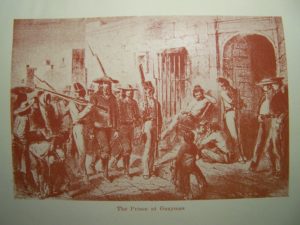

In between Gaston’s expeditions, central power in Mexico City changed hands once again. In the meantime the Mexicans had called the strongman General Santa Anna out of exile in Colombia to deal with Mexico’s various problems. Santa Anna soon found out of the count’s next expedition to Sonora and was prepared. The previous deal Gaston had made with the former president was null and void, and Santa Anna just wanted all foreigners out of Mexican territory. Loyalists in Guaymas attacked Gaston’s battalion soon after it landed and the French count was arrested and held for 17 days. His sentence was pronounced and he was to be shot by firing squad in the town square on August 13, 1854. At the time of his execution, Gaston outstretched his arms, exposing his chest and said, “My friends, I ask you not to fire at my head; aim at the heart and try to aim true.” The Mexican soldiers fired, but their aim was so terrible that not a single bullet hit him. An excited crowd cheered thinking that Gaston’s life had been spared. To the surprise of the townsfolk, the Sonoran governor ordered the soldiers to fire again. Gaston was hit 4 times and fell face first to the ground and in a small cloud of dust ended the dreams of a flowery French paradise in the northern deserts of Mexico.

In between Gaston’s expeditions, central power in Mexico City changed hands once again. In the meantime the Mexicans had called the strongman General Santa Anna out of exile in Colombia to deal with Mexico’s various problems. Santa Anna soon found out of the count’s next expedition to Sonora and was prepared. The previous deal Gaston had made with the former president was null and void, and Santa Anna just wanted all foreigners out of Mexican territory. Loyalists in Guaymas attacked Gaston’s battalion soon after it landed and the French count was arrested and held for 17 days. His sentence was pronounced and he was to be shot by firing squad in the town square on August 13, 1854. At the time of his execution, Gaston outstretched his arms, exposing his chest and said, “My friends, I ask you not to fire at my head; aim at the heart and try to aim true.” The Mexican soldiers fired, but their aim was so terrible that not a single bullet hit him. An excited crowd cheered thinking that Gaston’s life had been spared. To the surprise of the townsfolk, the Sonoran governor ordered the soldiers to fire again. Gaston was hit 4 times and fell face first to the ground and in a small cloud of dust ended the dreams of a flowery French paradise in the northern deserts of Mexico.

REFERENCE (Not a formal bibliography)

The Wolf Cub: The Great Adventures of Count Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon in California and Sonora, 1850-1854 by Maurice Soulié

2 thoughts on “The French Count and the Principality of Sonora”

Loved this! Guaymas was one of my favorite SCUBA diving places, back in the day. Spent several days in Hermosillo as a young lady too. Just hearing them referenced took me back in time! I had NO idea that France played such a part in Mexico\’s history!! Wow. Thanks for this lesson.

Thanks for the comment!