Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

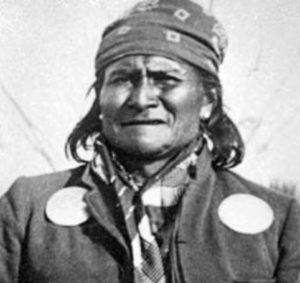

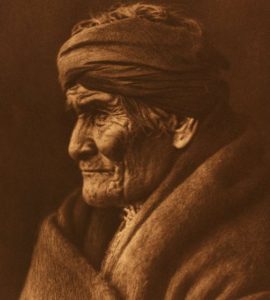

A few years after the turn of the century and well into his 70s, the aged Apache warrior known to non-Natives as Geronimo told his life story to an American journalist named S.M. Barrett. In Part II of Barrett’s book, the Apache leader relates a sad tale of one of the worst events of his life. Here are Geronimo’s own words:

A few years after the turn of the century and well into his 70s, the aged Apache warrior known to non-Natives as Geronimo told his life story to an American journalist named S.M. Barrett. In Part II of Barrett’s book, the Apache leader relates a sad tale of one of the worst events of his life. Here are Geronimo’s own words:

“In the summer of 1858, being at peace with the Mexican towns as well as with all the neighboring Indian tribes, we went south into Old Mexico to trade. Our whole tribe – Bedonkohe Apaches – went through Sonora toward Casas Grandes, our destination, but just before reaching that place we stopped at another Mexican town called by the Indians “Kas-ki-yeh” (Janos, Chihuahua). Here we stayed for several days, camping just outside the city. Every day we would go into town to trade, leaving our camp under the protection of a small guard so that our arms, supplies, and women and children would not be disturbed during our absence.

“Late one afternoon when returning from town we were met by a few women and children who told us that Mexican troops from some other town had attacked our camp, killed all the warriors of the guard, captured all our ponies, secured our arms, destroyed our supplies, and killed many women and children. Quickly we separated, concealing ourselves as best we could until nightfall, when we assembled at our appointed place of rendezvous – a thicket by the river.”

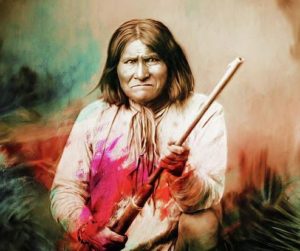

The date was March 5, 1858. Colonel José María Carrasco led 400 soldiers from the presidio at Arizpe, Sonora to roam across the northern reaches of Mexico to kill as many Apaches as possible. To the Mexican military officials, this was retribution for the many Apache raids that had plagued Spanish and Mexican settlements in the north of Mexico for centuries. Even though the band that Geronimo belonged to traveled south across the US-Mexico border just to engage in peaceful trade, Colonel Carrasco had had enough of marauding indios barbaros and saw all natives not settled into cities and towns as a threat. The Mexican colonel offered his men 100 pesos for the scalps of Apache men and 50 pesos for those of Apache women and children. After this massacre of the women and children left behind in the camp, Geronimo’s band led by chief Mangas Coloradas joined with the band of Apaches under the leadership of the legendary Cochise and set their sights on Arizpe. The Apaches attacked the garrison and left few survivors. Spurred on by the fresh memories of his murdered family, Geronimo engaged in vicious hand-to-hand combat with the Mexican soldiers using a knife. So the story goes, when Geronimo got close to killing his victim, the soldier would call out the name of Saint Jerome for help, and that, in Spanish is, “Geronimo.” From that point on, the warrior was called thus.

The date was March 5, 1858. Colonel José María Carrasco led 400 soldiers from the presidio at Arizpe, Sonora to roam across the northern reaches of Mexico to kill as many Apaches as possible. To the Mexican military officials, this was retribution for the many Apache raids that had plagued Spanish and Mexican settlements in the north of Mexico for centuries. Even though the band that Geronimo belonged to traveled south across the US-Mexico border just to engage in peaceful trade, Colonel Carrasco had had enough of marauding indios barbaros and saw all natives not settled into cities and towns as a threat. The Mexican colonel offered his men 100 pesos for the scalps of Apache men and 50 pesos for those of Apache women and children. After this massacre of the women and children left behind in the camp, Geronimo’s band led by chief Mangas Coloradas joined with the band of Apaches under the leadership of the legendary Cochise and set their sights on Arizpe. The Apaches attacked the garrison and left few survivors. Spurred on by the fresh memories of his murdered family, Geronimo engaged in vicious hand-to-hand combat with the Mexican soldiers using a knife. So the story goes, when Geronimo got close to killing his victim, the soldier would call out the name of Saint Jerome for help, and that, in Spanish is, “Geronimo.” From that point on, the warrior was called thus.

Geronimo’s native name was Goyathley, which translates into English as, “One Who Yawns.” He was born in the Gila Wilderness near Turkey Creek in the modern-day US state of New Mexico in June of 1829 when New Mexico was a far-flung territory of the new nation of Mexico. The Mexicans and the Spanish before them called Geronimo’s band of Apaches Gileños, since these people lived in the area near the upper reaches of the Gila River. The Mexican governor of the New Mexico Territory, Manuel Armijo, had a hands-off policy towards the Apache and the Chiricahua Bands were hundreds of miles away from the territory’s capital city of Santa Fe to be of any concern. Consequently, Geronimo had a very traditional childhood and his people roamed the mountains and deserts much as they had done since time immemorial. Geronimo’s grandfather was a chief named Mahko, but since Geronimo’s father married outside the band, he had no rights of succession, so although later in life he would often be referred to as an Apache chief, Geronimo could never become one and never claimed to be one.

Geronimo’s native name was Goyathley, which translates into English as, “One Who Yawns.” He was born in the Gila Wilderness near Turkey Creek in the modern-day US state of New Mexico in June of 1829 when New Mexico was a far-flung territory of the new nation of Mexico. The Mexicans and the Spanish before them called Geronimo’s band of Apaches Gileños, since these people lived in the area near the upper reaches of the Gila River. The Mexican governor of the New Mexico Territory, Manuel Armijo, had a hands-off policy towards the Apache and the Chiricahua Bands were hundreds of miles away from the territory’s capital city of Santa Fe to be of any concern. Consequently, Geronimo had a very traditional childhood and his people roamed the mountains and deserts much as they had done since time immemorial. Geronimo’s grandfather was a chief named Mahko, but since Geronimo’s father married outside the band, he had no rights of succession, so although later in life he would often be referred to as an Apache chief, Geronimo could never become one and never claimed to be one.

Among the stories told to him by his mother and grandmother in his childhood, Geronimo loved the most the story of the First Boy, and perhaps this story would play an important role in his later life, after the tragic loss of his family in the Mexican raid. In the times before the current age, the world was divided between the birds in the air and the beasts on the ground. It was a very dangerous time then, with the birds and the land beasts constantly at war, and there were very few people on the earth. Those few people lived a miserable existence always afraid of being eaten by the menacing beasts who roamed the land. One of the remaining women had all but one of her children eaten by a dragon covered in pointy scales. She hid her last surviving child in a cave and when the dragon came around looking for young children, the woman would tell the dragon that he ate all her children and there were no more. The boy grew and sometimes left the cave. When he became old enough to hunt, he made a bow and arrow and went out and killed a deer. While he was preparing the meat, the scaly dragon came around and tried to steal the deer meat. When the boy protested, the dragon threatened to eat him. The boy then challenged the dragon to a bow-and-arrow duel at 100 paces, 4 shots each. The dragon had a bow made of a tree and arrows made of saplings. He went first, shooting his arrows at the boy. The boy jumped and avoided each arrow. When it was the boy’s turn to shoot, he shot the dragon in the area of his heart, but the arrow only penetrated the first layer of his scales. He shot another arrow in the same spot and penetrated the next layer. Same with the third arrow. The fourth arrow made it to the dragon’s heart and killed him, thus making the world safe for humans again. This, the favorite Apache tale from his youth, must have inspired Geronimo when he was facing insurmountable odds.

After the revenge raid on the Mexican garrison at Arizpe in 1858, Geronimo took on mythical qualities of his own. Although he was not a chief, rumors circulated throughout Apache territory that he could never be killed by bullets. He was also said to be able to heal people by touch and engaged in a kind of remote viewing, able to see distant events as they were happening and even predict events. In a short time, Geronimo became one of the most respected and feared Apache leaders. The revenge on the Mexican garrison in Sonora was not the last time he would venture into Mexico, nor was it his most notable conflict.

In a broader context, Geronimo’s raids were part of what historians call the Apache-Mexico Wars. Although conflicts between Europeans, Mexican Mestizos and the Apache peoples date back to the 1600s, the most intense warfare occurred in the 1830s through the 1850s. The Spanish in the late 1700s and early 1800s paid a stipend to Apaches who gave up raiding and settled around the presidios and missions. Each Apache man was given weekly 30 liters of corn or wheat, a packet of cigarettes, a cake of brown sugar, salt, and 1/32nd of a butchered steer when available. Chiefs received more sugar and cigarettes, and women and children received a reduced amount of food. The Mexicans continued paying this until early 1831 when a group of bureaucrats in faraway Mexico City decided that these weekly payoffs were not worth it and there was no more money left in the Mexican treasury to continue this policy. The 2,000 or so Apaches who had settled down and were slowly adopting Mexican culture suddenly abandoned the presidios and went back to their marauding ways. With their sustenance abruptly taken from them, many of the formerly sedentary Apaches began attacking haciendas and stealing livestock just to survive. By the fall of the year the stipends ended, 1831, with raids exploding across Mexico’s northern states and territories, the Mexican military declared full-out war on the Apaches. By the time Geronimo came on the scene over two decades later, those in command of northern garrisons were sick of dealing with the Apaches and handled even mild situations with a heavy hand, hence the mass killing at Geronimo’s camp in 1858.

In a broader context, Geronimo’s raids were part of what historians call the Apache-Mexico Wars. Although conflicts between Europeans, Mexican Mestizos and the Apache peoples date back to the 1600s, the most intense warfare occurred in the 1830s through the 1850s. The Spanish in the late 1700s and early 1800s paid a stipend to Apaches who gave up raiding and settled around the presidios and missions. Each Apache man was given weekly 30 liters of corn or wheat, a packet of cigarettes, a cake of brown sugar, salt, and 1/32nd of a butchered steer when available. Chiefs received more sugar and cigarettes, and women and children received a reduced amount of food. The Mexicans continued paying this until early 1831 when a group of bureaucrats in faraway Mexico City decided that these weekly payoffs were not worth it and there was no more money left in the Mexican treasury to continue this policy. The 2,000 or so Apaches who had settled down and were slowly adopting Mexican culture suddenly abandoned the presidios and went back to their marauding ways. With their sustenance abruptly taken from them, many of the formerly sedentary Apaches began attacking haciendas and stealing livestock just to survive. By the fall of the year the stipends ended, 1831, with raids exploding across Mexico’s northern states and territories, the Mexican military declared full-out war on the Apaches. By the time Geronimo came on the scene over two decades later, those in command of northern garrisons were sick of dealing with the Apaches and handled even mild situations with a heavy hand, hence the mass killing at Geronimo’s camp in 1858.

For a decade and a half after the revenge attack on Arizpe, Geronimo and his band were involved in numerous attacks and counterattacks, including raids on Mexican and American settlements. Most of Geronimo’s activity happened south of the border, though, at it seemed like for a time that the Chiricahuas were establishing a new homeland for themselves in the Sierra Madres of Chihuahua and Sonora. Although this land of beautiful mountains and valleys was considered Opata territory, the Opatas lived peacefully alongside the Apaches and didn’t mind their new neighbors. In 1860, after one of Geronimo’s cross-border raids, the Mexican cavalry followed him into American territory and skirmished with his people. This may have been the first and only time that a foreign army did battle within the borders of the United States since the War of 1812. In the few times when Geronimo and his men suffered minor defeats or pushbacks at the hands of the Mexicans, the Apaches risked having their captured women and children sold into servitude. Although Mexico officially abolished slavery in 1829, Mexican soldiers often treated the female and child prisoners taken in battle as their personal property. Apache women and children were trained as servants for the households of military families or sold off to work as domestics in the larger Mexican cities to the south, like Guadalajara or Mexico City. Geronimo himself later made comments about the topic of war captives in the lengthy interview that turned into his biography years later. Here are Geronimo’s own words:

“Many women and children were carried away at different times by Mexicans. Not many of them ever returned, and those who did underwent many hardships in order to be again united with our people. Those who did not escape were slaves to the Mexicans, or perhaps even more degraded.

“When warriors were captured by the Mexicans they were kept in chains. Four warriors who were captured once at a place north of Casas Grandes, called by the Indians ‘Honas,’ were kept in chains for a year and a half, when they were exchanged for Mexicans whom we had captured.

“We never chained prisoners or kept them in confinement, but they seldom got away. Mexican men we captured were compelled to cut wood and herd horses. Mexican women and children were treated as our own people.”

After months of prolonged fighting in 1873, it seemed as if the Mexicans and Geronimo would finally come together and hash out a peace treaty. The Apaches met the Mexicans at Casas Grandes and signed a treaty after agreeing to terms. After they made peace, some military men gave the Apaches mezcal to celebrate. The Mexican military then attacked the Apaches in their camp while they were intoxicated, killing 20 and capturing many more. Geronimo was on the run again.

After months of prolonged fighting in 1873, it seemed as if the Mexicans and Geronimo would finally come together and hash out a peace treaty. The Apaches met the Mexicans at Casas Grandes and signed a treaty after agreeing to terms. After they made peace, some military men gave the Apaches mezcal to celebrate. The Mexican military then attacked the Apaches in their camp while they were intoxicated, killing 20 and capturing many more. Geronimo was on the run again.

The United States used a full one fourth of its Army to hunt down Geronimo but they could not capture him. The Mexican government even gave permission to the US military to cross the border south to pursue this legendary warrior. Geronimo eventually surrendered to General George Crook on March 27, 1886 in the Sierra Madre of Mexico, near the Chihuahua/Sonora border and about 20 miles south of the international line. Geronimo was not cornered nor in any dire situation that caused him to surrender. Many of his men were homesick for their families and wanted to put an end to their marauding way of life and just return home to Arizona. Geronimo and most of his band were treated as prisoners of war and shipped off to a prison in Florida. Later he was transferred to an Apache reservation in Oklahoma, never going back to the Gila Wilderness of Arizona and New Mexico as he had wanted. In his later years, the old Indian fighter traveled around the United States under a limited form of house arrest, and appeared at 4th of July celebrations, Wild West shows, the 1904 World’s Fair and even in the inaugural parade for President Teddy Roosevelt.

A few years before his death Geronimo had his final say about Mexico and the Mexicans. What had started off as a terrible relationship did not age well with time. Geronimo said this about his Mexican exploits: “I have killed many Mexicans; I do not know how many, for frequently I did not count them. Some of them were not worth counting. It has been a long time since then, but still I have no love for the Mexicans. With me they were always treacherous and malicious.”

REFERENCES

Barrett, S.M. Geronimo’s Story of His Life. New York: Duffield and Company, 1906. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/36YIxRd