Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

I t was a hot and steamy day in the Yucatán. The date was July 12, 1562. In front of the Monastery of San Miguel Arcangel in the center of the Maya town of Maní a Franciscan friar named Diego de Landa was about to perform a great auto-de-fé, a ceremony commonly used in the Spanish Inquisition to punish heretics, but in this ceremony there were to be no people burned at the stake. Instead, in front of the freshly painted orange building which had only been built 13 years earlier by the Spanish from the stones of nearby Maya ruins, there was a massive pile of assorted artifacts. Among the 5,000 or so pieces – mostly what were described as wooden “idols” – were 27 bark paper books. These books, also called codices, were passed down through the centuries among the Maya elite and priestly classes. Beautifully illustrated, they were made of either bark paper or deer hide and contained historical accounts, astronomical observations and sacred instructions for the Maya priests. Diego de Landa could not read the books, and there were very few Maya left who could, but he knew that they had to be destroyed along with the physical remnants of the old Maya religion that were on that pile in front of the monastery waiting to be torched. The Franciscan would later recall the event with specific reference to the Maya codices. Years later in Spain de Landa would say,

t was a hot and steamy day in the Yucatán. The date was July 12, 1562. In front of the Monastery of San Miguel Arcangel in the center of the Maya town of Maní a Franciscan friar named Diego de Landa was about to perform a great auto-de-fé, a ceremony commonly used in the Spanish Inquisition to punish heretics, but in this ceremony there were to be no people burned at the stake. Instead, in front of the freshly painted orange building which had only been built 13 years earlier by the Spanish from the stones of nearby Maya ruins, there was a massive pile of assorted artifacts. Among the 5,000 or so pieces – mostly what were described as wooden “idols” – were 27 bark paper books. These books, also called codices, were passed down through the centuries among the Maya elite and priestly classes. Beautifully illustrated, they were made of either bark paper or deer hide and contained historical accounts, astronomical observations and sacred instructions for the Maya priests. Diego de Landa could not read the books, and there were very few Maya left who could, but he knew that they had to be destroyed along with the physical remnants of the old Maya religion that were on that pile in front of the monastery waiting to be torched. The Franciscan would later recall the event with specific reference to the Maya codices. Years later in Spain de Landa would say,

“These people also made use of certain characters or letters, with which they wrote in their books their ancient matters and their sciences, and by these and by drawings and by certain signs in these drawings, they understood their affairs and made others understand them and taught them. We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which there were not to be seen superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.”

Today, many Maya scholars and students of history liken de Landa’s acts to the burning of the Library of Alexandria. It is unknown what ancient knowledge was forever lost on that massive cultural funeral pyre on that hot summer day in 1562.

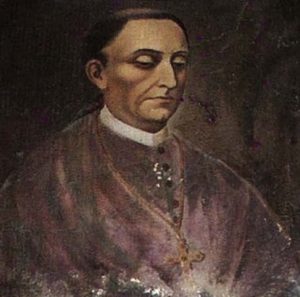

What would motivate a man to engage in such cultural destruction? Diego de Landa was born in the small town of Cifuentes in central Spain in November of 1524. He became a Franciscan monk in 1541 at the age of 17. Eight years later de Landa was sent to the Yucatán as part of one of the first contingents of Catholic clergy to enter the newly conquered territory. At the time of his arrival Christianity had been adopted by most of the indigenous population of the Yucatán, although rumors of human sacrifice and use of magic and sorcery pervaded the region. The young and enthusiastic de Landa was assigned to the mission of San Antonio at Izamal and was appointed assistant to the guardian of the mission. Besides a brief stint in Guatemala, Diego de Landa rose through the Franciscan hierarchy in the Yucatán and by September of 1561 de Landa was elected as the first “Ministro Provincial” and first “definidor” of the new Franciscan province of San José de Yucatán y Guatemala. From what is known, de Landa approached all of his tasks with zeal and invoked the full authority his various offices commanded. So, when accusations of idolatry and a return to the worship of the old Maya gods began to surface in the Spring of 1562 in and around the town of Maní, de Landa began an Inquisition, gathering information and physical evidence to make the case that the people under his ecclesiastical control had strayed away from the Catholic Church. While many examples of the auto-de-fé in the Spanish Inquisition included people being burned at the stake, de Landa thought it more fitting to erase all evidence of physical culture that would connect the Maya to their ancient past. The Maya elites and commoners alike protested the massive destruction of their religious carvings and their sacred books, and the harsh treatment of those allegedly involved in the practicing of the ancient rituals and those who kept hidden caches of idols secret. As a method of interrogation, de Landa and the inquisitors subjected those being examined to a practice known as “hoisting.” In hoisting, a victim’s bound hands were pulled above their heads until their body hung suspended off the ground. Often times the victim was weighted down with heavy stones or lashed with a whip in order to obtain more information. As word spread about what had happened in Maní, De Landa’s actions garnered special attention from other religious and civilian authorities throughout the Spanish territories. Decades before, Crown fiat had exempted the indigenous people of the New World from the Spanish Inquisition because, as it was reasoned, the Indians’ knowledge and understanding of Christianity was “too childish” and thus they were not to be held responsible for their own heresies and blasphemy. De Landa also refused to follow certain strict Inquisition protocols, including creating the proper documentation connected with the interrogation process. The emergency measures were justified, de Landa later claimed, because there existed a simmering movement

What would motivate a man to engage in such cultural destruction? Diego de Landa was born in the small town of Cifuentes in central Spain in November of 1524. He became a Franciscan monk in 1541 at the age of 17. Eight years later de Landa was sent to the Yucatán as part of one of the first contingents of Catholic clergy to enter the newly conquered territory. At the time of his arrival Christianity had been adopted by most of the indigenous population of the Yucatán, although rumors of human sacrifice and use of magic and sorcery pervaded the region. The young and enthusiastic de Landa was assigned to the mission of San Antonio at Izamal and was appointed assistant to the guardian of the mission. Besides a brief stint in Guatemala, Diego de Landa rose through the Franciscan hierarchy in the Yucatán and by September of 1561 de Landa was elected as the first “Ministro Provincial” and first “definidor” of the new Franciscan province of San José de Yucatán y Guatemala. From what is known, de Landa approached all of his tasks with zeal and invoked the full authority his various offices commanded. So, when accusations of idolatry and a return to the worship of the old Maya gods began to surface in the Spring of 1562 in and around the town of Maní, de Landa began an Inquisition, gathering information and physical evidence to make the case that the people under his ecclesiastical control had strayed away from the Catholic Church. While many examples of the auto-de-fé in the Spanish Inquisition included people being burned at the stake, de Landa thought it more fitting to erase all evidence of physical culture that would connect the Maya to their ancient past. The Maya elites and commoners alike protested the massive destruction of their religious carvings and their sacred books, and the harsh treatment of those allegedly involved in the practicing of the ancient rituals and those who kept hidden caches of idols secret. As a method of interrogation, de Landa and the inquisitors subjected those being examined to a practice known as “hoisting.” In hoisting, a victim’s bound hands were pulled above their heads until their body hung suspended off the ground. Often times the victim was weighted down with heavy stones or lashed with a whip in order to obtain more information. As word spread about what had happened in Maní, De Landa’s actions garnered special attention from other religious and civilian authorities throughout the Spanish territories. Decades before, Crown fiat had exempted the indigenous people of the New World from the Spanish Inquisition because, as it was reasoned, the Indians’ knowledge and understanding of Christianity was “too childish” and thus they were not to be held responsible for their own heresies and blasphemy. De Landa also refused to follow certain strict Inquisition protocols, including creating the proper documentation connected with the interrogation process. The emergency measures were justified, de Landa later claimed, because there existed a simmering movement  throughout the Yucatán which sought to take away religious authority from the Christians and reestablish a pagan way of life, including a return to rule by Maya kings. The month after de Landa’s book burning, the Yucatán got a new bishop, a man named Francisco Toral. De Landa’s reputation had preceded him and the new bishop knew he had to deal with de Landa or face discontent and possible unrest in his new bishopric. Bishop Toral called for de Landa’s resignation which then prompted the Franciscan friar to go to Mexico City to present his grievances to the church and civil authorities there. While de Landa was in Mexico City, Bishop Toral dispatched orders to the authorities in central Mexico and the Yucatán, demanding that Diego de Landa and other friars who participated in the Maní Inquisition be sent to Spain to face judgement of their actions before the Council of the Indies. It took de Landa 18 months to reach Spain, having been delayed by serious illness and a shipwreck. After almost 4 years of deliberation and changing jurisdictions, the Council of the Indies eventually handed de Landa off to the highest Franciscan authority in Castille. He was acquitted of all charges an exonerated of all wrongdoing in January of 1569. Not only that, on April 30, 1572, the Spanish king, Phillip the Second, made Diego de Landa the new Bishop of the Yucatán after the death of his bitter rival, Bishop Francisco Toral. Diego de Landa promptly returned to the New World to assume his new position of power and died almost exactly seven years later, on April 29, 1579, in the city of Mérida, at the age of 54.

throughout the Yucatán which sought to take away religious authority from the Christians and reestablish a pagan way of life, including a return to rule by Maya kings. The month after de Landa’s book burning, the Yucatán got a new bishop, a man named Francisco Toral. De Landa’s reputation had preceded him and the new bishop knew he had to deal with de Landa or face discontent and possible unrest in his new bishopric. Bishop Toral called for de Landa’s resignation which then prompted the Franciscan friar to go to Mexico City to present his grievances to the church and civil authorities there. While de Landa was in Mexico City, Bishop Toral dispatched orders to the authorities in central Mexico and the Yucatán, demanding that Diego de Landa and other friars who participated in the Maní Inquisition be sent to Spain to face judgement of their actions before the Council of the Indies. It took de Landa 18 months to reach Spain, having been delayed by serious illness and a shipwreck. After almost 4 years of deliberation and changing jurisdictions, the Council of the Indies eventually handed de Landa off to the highest Franciscan authority in Castille. He was acquitted of all charges an exonerated of all wrongdoing in January of 1569. Not only that, on April 30, 1572, the Spanish king, Phillip the Second, made Diego de Landa the new Bishop of the Yucatán after the death of his bitter rival, Bishop Francisco Toral. Diego de Landa promptly returned to the New World to assume his new position of power and died almost exactly seven years later, on April 29, 1579, in the city of Mérida, at the age of 54.

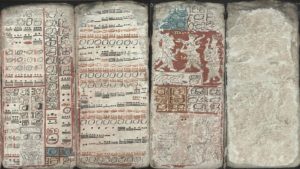

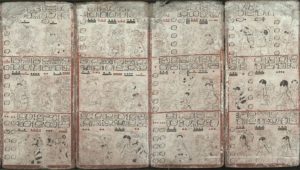

Although he thought he had gathered all of the ancient Maya books in his jurisdiction, de Landa missed a few, perhaps those that had already managed to get to Europe. There are three codices that have been accepted as authentic, and fragments of others found by archaeologists over the years, and rumors of others, and several fakes. The three known Maya codices surviving to this day include the Madrid Codex, the Paris Codex and the Dresden Codex. The National Archaeological Museum of Spain acquired the Madrid Codex from a collector in 1872. The book was originally called the Cortesianus Codex because it had been believed that Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés brought it back from Mexico in the mid-1500s. The Madrid Codex may date back to as early as 1250 AD and because of its stylistic variety, it was possible that it was authored by 8 or 9 different people, members of the priestly class who were also scribes. This codex features astronomical tables, almanacs and horoscope material and it is  theorized that it was used to help aid priests in divination. The Paris Codex was acquired by the Imperial Library of France in 1832. It was neglected for a few decades before it underwent serious study and is said to contain the Maya zodiac and predictions for the future. Of the three known codices, the Paris Codex is in the worst condition. It dates back to the Early Post-Classic period of Maya history and may have been created as early as 900 AD. Some theorize that it may be a copy of an earlier work made during the apex of Maya civilization centuries before. The Dresden Codex is the most detailed and the largest of the ancient Mayan codices. It is screen-folded, much like an accordion, and contains 39 pages, written on both sides. It contains a vast almanac of information about religious rituals in addition to having very detailed astronomical data including what has been called “the Venus tables” and information on eclipses. The Dresden Codex dates to around the year 1250. Because of its detail and quantity of information, the study of this codex played an instrumental role in deciphering the Maya script. For further information about the Maya writing system, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 16. As mentioned before, there have been fragments of Maya codices found at archaeological sites throughout Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and Belize. There have even been large clumps of calcified organic material discovered that scientists believe may be codices but the technology doesn’t exist yet to “open” the books to see what may be inside.

theorized that it was used to help aid priests in divination. The Paris Codex was acquired by the Imperial Library of France in 1832. It was neglected for a few decades before it underwent serious study and is said to contain the Maya zodiac and predictions for the future. Of the three known codices, the Paris Codex is in the worst condition. It dates back to the Early Post-Classic period of Maya history and may have been created as early as 900 AD. Some theorize that it may be a copy of an earlier work made during the apex of Maya civilization centuries before. The Dresden Codex is the most detailed and the largest of the ancient Mayan codices. It is screen-folded, much like an accordion, and contains 39 pages, written on both sides. It contains a vast almanac of information about religious rituals in addition to having very detailed astronomical data including what has been called “the Venus tables” and information on eclipses. The Dresden Codex dates to around the year 1250. Because of its detail and quantity of information, the study of this codex played an instrumental role in deciphering the Maya script. For further information about the Maya writing system, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 16. As mentioned before, there have been fragments of Maya codices found at archaeological sites throughout Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and Belize. There have even been large clumps of calcified organic material discovered that scientists believe may be codices but the technology doesn’t exist yet to “open” the books to see what may be inside.

While the great Maya book burning may be considered the greatest loss of ancient knowledge of the peoples of Mesoamerica, it is quite ironic that the person who created so much destruction of knowledge is also credited as being the greatest chronicler of the Maya and the one who can be credited with most of what we know today about the indigenous people of the Yucatán at the time of the Conquest and immediately before. While awaiting his judgment in Spain, Deigo de Landa wrote a book called, Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English, Reference of the Things of the Yucatán, in which he described in great detail the daily life, customs and beliefs of the Maya people he ministered to. Like many early members of the clergy in the New World, de Landa wanted to understand the people of his jurisdiction the best he could, so he observed things much like a cultural anthropologist would and took meticulous notes. He chronicled everything from the months and festivals of the Mayan calendar, to the significance of jewelry to Mayan women, to native military organization of the region, to genealogies of prominent Maya families. Some scholars believe that 90% of what we know of the Post-Classic and colonial-era Maya comes from de Landa’s Relación. In spite of whatever accolades de Landa will get for his keen anthropological eye and his attention to detail, we will never know what was destroyed in the great Maya book burning of 1562. The loss to Mexico and to the world is unmeasurable.

While the great Maya book burning may be considered the greatest loss of ancient knowledge of the peoples of Mesoamerica, it is quite ironic that the person who created so much destruction of knowledge is also credited as being the greatest chronicler of the Maya and the one who can be credited with most of what we know today about the indigenous people of the Yucatán at the time of the Conquest and immediately before. While awaiting his judgment in Spain, Deigo de Landa wrote a book called, Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English, Reference of the Things of the Yucatán, in which he described in great detail the daily life, customs and beliefs of the Maya people he ministered to. Like many early members of the clergy in the New World, de Landa wanted to understand the people of his jurisdiction the best he could, so he observed things much like a cultural anthropologist would and took meticulous notes. He chronicled everything from the months and festivals of the Mayan calendar, to the significance of jewelry to Mayan women, to native military organization of the region, to genealogies of prominent Maya families. Some scholars believe that 90% of what we know of the Post-Classic and colonial-era Maya comes from de Landa’s Relación. In spite of whatever accolades de Landa will get for his keen anthropological eye and his attention to detail, we will never know what was destroyed in the great Maya book burning of 1562. The loss to Mexico and to the world is unmeasurable.

REFERENCES

Coe, Michael D. Breaking the Maya Code. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1992.

Coe, Michael D. The Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Gates, William. Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. New York: Dover Publications, 1978.

One thought on “The Great Maya Book Burning”

A sad and tragic piece off history so well and interestingly written! It motivates me to search for more information. We have been deprived of so much very important information of a wonderful and impressive people!