Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

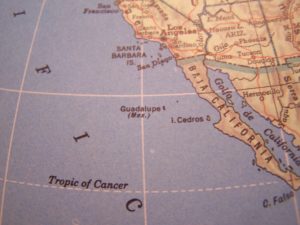

Very few people have heard of Mexico’s most western possession, Guadalupe Island or Isla Guadalupe in Spanish. In the Pacific Ocean, 150 miles off the coast of the Baja Peninsula and 261 miles south of San Diego, the island measures 22 miles long almost 6 miles across. Guadalupe has 11 small islands and rocks around it. Off the main island’s northwest coast at 118° 22” West longitude is Roca Elefante, which is not only the westernmost point in Mexico, but the westernmost point in all of Latin America. Millions of years old, the island was formed when two volcanoes erupted on the ocean floor. The two volcanoes make up the island’s tallest mountains, Mount Augusta at 4,259 feet and El Picacho at 3,199 feet. Being so isolated from the Mexican mainland, Guadalupe Island developed its own unique ecosystem and is home to many distinct animal and plant species. Pirates, naturalists, adventurers, crazy entrepreneurs, Yankee whalers, the Mexican military and most of all goats have all played starring roles in Isla Guadalupe’s interesting history.

Very few people have heard of Mexico’s most western possession, Guadalupe Island or Isla Guadalupe in Spanish. In the Pacific Ocean, 150 miles off the coast of the Baja Peninsula and 261 miles south of San Diego, the island measures 22 miles long almost 6 miles across. Guadalupe has 11 small islands and rocks around it. Off the main island’s northwest coast at 118° 22” West longitude is Roca Elefante, which is not only the westernmost point in Mexico, but the westernmost point in all of Latin America. Millions of years old, the island was formed when two volcanoes erupted on the ocean floor. The two volcanoes make up the island’s tallest mountains, Mount Augusta at 4,259 feet and El Picacho at 3,199 feet. Being so isolated from the Mexican mainland, Guadalupe Island developed its own unique ecosystem and is home to many distinct animal and plant species. Pirates, naturalists, adventurers, crazy entrepreneurs, Yankee whalers, the Mexican military and most of all goats have all played starring roles in Isla Guadalupe’s interesting history.

As Guadalupe Island is located far from the mainland, no Native American group ever visited the island or knew of its existence. The first documented visitor was Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaino who sighted the island and sent a party ashore in 1602. Vizcaino was looking for new stopover places for Spanish galleons making the Pacific crossing from the Spanish Philippines to New Spain. The next visitor to the island may have been Norfolk-born English pirate John Clipperton who history credits with discovering a volcanic outcrop of steep islets and rocks now known as the Rocas Alijos or Escollos Alijos some 300 miles south of Guadalupe Island. In the early years of the 1700s Clipperton preyed on the Spanish galleons carrying goods from the Far East, and some stories say that he may have stashed some of his pirate loot somewhere on Guadalupe Island. English pirates and other assorted castaways and miscreants would be the island’s only visitors until the early 1800s.

In 1807 while technically still geographically part of New Spain, American Samuel Chapman landed on Guadalupe and left an inscription along with a US flag and claimed the island for the young United States. Chapman and his crew spent a few months on the island before moving on. In the early part of the 1800s Isla Guadalupe saw the arrival of whaling vessels and those attracted to the island for its fur and elephant seal populations. Seal fur and oil were highly prized at this time. Those hunting whales and seals were either English, American, Japanese or Russians from Alaska. At the time before Mexico’s independence from Spain, only the Russians had a legal right to be on the island as they were the only ones allowed to trade with the Spanish colonies of California and what is now the Pacific coast of Mexico. It was sometime during the early 1800s when whalers and other passing ships may have released goats on the island to multiply and to ensure a future food source. By the 1830s, goats had taken over the island and were described by whalers and sealers as being of great size. The destruction of the fragile environment on Isla Guadalupe seemed like a sealed fate by this time.

After Mexican independence, the Mexicans claimed Isla Guadalupe as part of their national territory but did nothing with the island until 1839. On January 8, 1839 the central government in Mexico City sold this far-flung piece of its territory to two Mexican businessmen, José Castro and Florencio Ferrano. The two not only received Isla Guadalupe and its surrounding islands but the 3 islets and smaller rocks of the Rocas Alijos group hundreds of miles to the south. As the Mexican government was far away from these remote Pacific territories, Castro and Ferrano administered the islands as their own private country unmolested by authorities in Mexico City. The pair had exclusive rights to hunting seals and goats and could do whatever they wanted with the territory granted to them. The goat population was enormous at the time of the reign of Castro and Ferrano and the two had quite a business selling goat meat and hides to the Mexican mainland, using Indians from Sonora as a type of slave labor to kill goats and seals and to raise vegetables in the island’s fertile soil. They built a small town with several structures and workshops and christened it San José de Guadalupe. Castro and Ferrano also engaged in lucrative business with passing ships, whenever the opportunity arose. It was not for the lack of goats that the two eventually ceased their operations on Guadalupe Island. History does not record why, but by 1845 that José Castro sold off his share in the islands for the equivalent of $500 in gold. Sometime in the late 1840s the island was completely abandoned and left to the goats once again.

After Mexican independence, the Mexicans claimed Isla Guadalupe as part of their national territory but did nothing with the island until 1839. On January 8, 1839 the central government in Mexico City sold this far-flung piece of its territory to two Mexican businessmen, José Castro and Florencio Ferrano. The two not only received Isla Guadalupe and its surrounding islands but the 3 islets and smaller rocks of the Rocas Alijos group hundreds of miles to the south. As the Mexican government was far away from these remote Pacific territories, Castro and Ferrano administered the islands as their own private country unmolested by authorities in Mexico City. The pair had exclusive rights to hunting seals and goats and could do whatever they wanted with the territory granted to them. The goat population was enormous at the time of the reign of Castro and Ferrano and the two had quite a business selling goat meat and hides to the Mexican mainland, using Indians from Sonora as a type of slave labor to kill goats and seals and to raise vegetables in the island’s fertile soil. They built a small town with several structures and workshops and christened it San José de Guadalupe. Castro and Ferrano also engaged in lucrative business with passing ships, whenever the opportunity arose. It was not for the lack of goats that the two eventually ceased their operations on Guadalupe Island. History does not record why, but by 1845 that José Castro sold off his share in the islands for the equivalent of $500 in gold. Sometime in the late 1840s the island was completely abandoned and left to the goats once again.

By the early 1850s, Guadalupe Island attracted the attention of the Americans once again, but this time not for seals or whales but for guano, the calcified bird droppings highly prized in fertilizer manufacturing. The United States had recently acquired California in the Mexican Cession after the Mexican War and some Americans who saw Isla Guadalupe as a gold mine for guano claimed that the island belonged to the United States as a part of California. In November of 1850, U.S. Army Lt. George H. Derby passed Guadalupe Island on his expedition in the U.S. Transport Invincible. Ashore he planted the American flag and described the island in his diaries in great detail, noting the abundance of vegetation – including cypress and palm forests – the large elephant seal population, and of course, the huge population of goats. He described the animals as being of “unusual size.” While the Mexican government turned a blind eye to the seal harvesting on the island, it could not disregard the American interest in guano mining on Guadalupe. In 1856, the United States Congress passed the Guano Islands Act that enabled US citizens to take possession of any uninhabited and unclaimed islands containing guano deposits. The act also empowered the President of the United States to use the US military to defend any guano mining operations on any claimed guano island. The act states:

“Whenever any citizen of the United States discovers a deposit of guano on any island, rock, or key, not within the lawful jurisdiction of any other Government, and not occupied by the citizens of any other Government, and takes peaceable possession thereof, and occupies the same, such island, rock, or key may, at the discretion of the President, be considered as appertaining to the United States.”

Because of “guano mania” of the 1850s, some American guano mining companies believed that the Guano Islands Act applied to the uninhabited Guadalupe Island even though it was clearly part of Mexican territory and had permanent settlements inhabited by Mexicans in the 1840s. After twelve tons of guano had been mined on Guadalupe in 1857 without the permission of the Mexican government, authorities in Mexico City decided to crack down on all activities on the island. Rival companies each put about a dozen settlers on the island in an attempt to make solid claims to the Mexican government to obtain mining concessions. The bureaucracy in Mexico City moved very slowly on their remote island outpost and eventually the Americans withdrew their claims, tired of waiting for the bureaucrats to make up their minds.

Another historical chapter opened for Isla Guadalupe after the guano mania died down in the 1860s. The Mexican territory of Baja California saw a small revolution in its government. Governor Feliciano Esparza was ousted by Matias Moreno, and like Napoleon’s exile to Elba, Esparza was banished to Isla Guadalupe with his family. At the time, the Esparzas were the only inhabitants on the islands and lived a Robinson-Crusoe-like existence. The former governor and his family subsisted off meat from the wild goats, bird eggs, seal meat and the scant fruits and vegetables that were growing wild from the days of Castro and Ferrano 20 years before. The family spent almost two years in exile there until a passing schooner spotted their signal fire and rescued them, taking the Esparzas to San Diego. Local newspapers told the tale of the banishment and even described the clothes and shoes the family had managed to fashion out of “hides that were spotted with black and white and made very beautiful clothing.” The Esparzas eventually settled in Santa Barbara, California, and never returned to Mexico.

Another historical chapter opened for Isla Guadalupe after the guano mania died down in the 1860s. The Mexican territory of Baja California saw a small revolution in its government. Governor Feliciano Esparza was ousted by Matias Moreno, and like Napoleon’s exile to Elba, Esparza was banished to Isla Guadalupe with his family. At the time, the Esparzas were the only inhabitants on the islands and lived a Robinson-Crusoe-like existence. The former governor and his family subsisted off meat from the wild goats, bird eggs, seal meat and the scant fruits and vegetables that were growing wild from the days of Castro and Ferrano 20 years before. The family spent almost two years in exile there until a passing schooner spotted their signal fire and rescued them, taking the Esparzas to San Diego. Local newspapers told the tale of the banishment and even described the clothes and shoes the family had managed to fashion out of “hides that were spotted with black and white and made very beautiful clothing.” The Esparzas eventually settled in Santa Barbara, California, and never returned to Mexico.

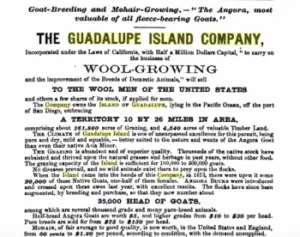

By 1870 the goat population on Isla Guadalupe had surpassed 50,000. The Mexican government at the time seemed disinterested in the activities on the island and Americans out of California made regular runs to the island to kill goats and sell their hides, tallow and meat in the markets of San Diego and San Francisco. Corrals and processing stations were built and between 3,000 and 10,000 goats were killed in any given year. This did not even put a dent in the goat population which seemed to ravage the landscape more and more with each passing year. In 1873, a lawsuit even appeared in the California newspapers between two rival entrepreneurs who allegedly had conflicting land claims on Guadalupe Island ending in a cash settlement even though the two parties had no formal permission by the Mexican government to operate on the island. In the same year, 1873, a group of businessmen in San Francisco issued $500,000 shares of stock, priced at $50 a share and formed the Guadalupe Island company. The scheme was to extract resources from the island, primarily focusing on the goats, which numbered around 100,000 at the time. Part of the plan was to import dozens of male goats of the angora variety to breed with the short-haired goats on the island and sell the meat and the fleece from the goats over the years. The president of the Guadalupe Island Company, William Landrum, owned a goat ranch in Santa Cruz, California and specialized in the angora variety. The principals of the company believed that the operation would net hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. By 1874 1,000 angora ewes and bucks were transported to Guadalupe Island and breeding commenced. In 1882 the Guadalupe Island Company sold their profitable venture and transferred their rights to the island to the Western Land and Live Stock Company which continued to operate on the island processing goats until the political situation in Mexico reversed their good fortune.

By 1870 the goat population on Isla Guadalupe had surpassed 50,000. The Mexican government at the time seemed disinterested in the activities on the island and Americans out of California made regular runs to the island to kill goats and sell their hides, tallow and meat in the markets of San Diego and San Francisco. Corrals and processing stations were built and between 3,000 and 10,000 goats were killed in any given year. This did not even put a dent in the goat population which seemed to ravage the landscape more and more with each passing year. In 1873, a lawsuit even appeared in the California newspapers between two rival entrepreneurs who allegedly had conflicting land claims on Guadalupe Island ending in a cash settlement even though the two parties had no formal permission by the Mexican government to operate on the island. In the same year, 1873, a group of businessmen in San Francisco issued $500,000 shares of stock, priced at $50 a share and formed the Guadalupe Island company. The scheme was to extract resources from the island, primarily focusing on the goats, which numbered around 100,000 at the time. Part of the plan was to import dozens of male goats of the angora variety to breed with the short-haired goats on the island and sell the meat and the fleece from the goats over the years. The president of the Guadalupe Island Company, William Landrum, owned a goat ranch in Santa Cruz, California and specialized in the angora variety. The principals of the company believed that the operation would net hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. By 1874 1,000 angora ewes and bucks were transported to Guadalupe Island and breeding commenced. In 1882 the Guadalupe Island Company sold their profitable venture and transferred their rights to the island to the Western Land and Live Stock Company which continued to operate on the island processing goats until the political situation in Mexico reversed their good fortune.

In 1885 the Mexican Consul-General in New York, Juan N. Navarro, demanded that the Guadalupe Island Company and the Western Land and Live Stock Company appear before a court in Baja California to determine the rights of ownership of Guadalupe Island and to prove a history of title. The companies refused, and later that year the Mexican military sent a gunboat to the island and occupied it, kicking out the Americans and shutting down all operations. The Mexicans built a military encampment with the goal of establishing a permanent government-controlled Mexican presence on Isla Guadalupe for the first time in the island’s history. Two years later, in 1887, the authorities in Mexico City granted the Mexican International Company the rights to exploit the island as others had in the past, primarily to make money from selling goat products to the Mexican mainland. The government banned all foreigners from its westernmost territory.

Sometime in the 1890s the Mexicans abandoned its garrison on Isla Guadalupe and the island again was left to the goats. The Mexican military occasionally would patrol the waters around the island looking for poachers and apprehended any people on and around Guadalupe. In the early 1900s the island had become a destination not only for goat and seal poachers but for explorers seeking pirate treasure and naturalists studying and collecting samples of exotic flora. In 1910 the Mexican government granted a concession to Los Angeles businessman Alfred Marcuson to take goats off the island and the Marcuson operation only lasted a few years. By 1928 the island became permanently off limits as a protected nature reserve, the oldest in Mexico, but the new restrictions did not deter visitors. An article in the September 6, 1931 edition of the San Bernardino Sun tells the woeful tale of 7 people stranded on the island for months. The party went there to poach goats and to search for pirate treasure. They were rescued by Los Angeles millionaire G. Allan Hancock who happened to sail by the island in his palatial yacht the Valero III.

Sometime in the 1890s the Mexicans abandoned its garrison on Isla Guadalupe and the island again was left to the goats. The Mexican military occasionally would patrol the waters around the island looking for poachers and apprehended any people on and around Guadalupe. In the early 1900s the island had become a destination not only for goat and seal poachers but for explorers seeking pirate treasure and naturalists studying and collecting samples of exotic flora. In 1910 the Mexican government granted a concession to Los Angeles businessman Alfred Marcuson to take goats off the island and the Marcuson operation only lasted a few years. By 1928 the island became permanently off limits as a protected nature reserve, the oldest in Mexico, but the new restrictions did not deter visitors. An article in the September 6, 1931 edition of the San Bernardino Sun tells the woeful tale of 7 people stranded on the island for months. The party went there to poach goats and to search for pirate treasure. They were rescued by Los Angeles millionaire G. Allan Hancock who happened to sail by the island in his palatial yacht the Valero III.

Throughout most of the 20th Century Isla Guadalupe received very few visitors. The Mexican government established a weather station there and built a landing strip in the center of the island. In the 1990s the island became a focus of intensive conservation efforts. 5 species of birds are native to this place, and 16% of the plants are found nowhere else on earth. By the final decade of the 20th Century non-profit organizations working with the Mexican government eradicated most of the invasive animals, including feral cats and mice. The goats remained a nagging problem and the only stumbling block to returning Guadalupe Island to its pre-human pristine state. By 2007, all the goats were either killed or relocated to the Mexican mainland. Now, the Mexican government only permits scientists to visit the island with a military escort. With the goats gone and human access severely limited, Guadalupe Island will soon heal itself and serve as an example of conservation for generations to come.

REFERENCES

Islapedia web site.

León-de la Luz, José & Rebman, Jon & Oberbauer, Thomas. (2003). “On the Urgency of Conservation on Guadalupe Island, Mexico: Is it a lost paradise?” Biodiversity and Conservation – 12. 1073-1082.

Smith, Gordon. “Guadalupe, 250 Miles South of San Diego, Eaten by Goats.” San Diego Reader. 10 Jul. 1980.