Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

It was a warm day in Mexico City. The date was July 31, 2002. The aged Catholic pope, John Paul the Second, arrived at the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe, after passing hundreds of thousands of people lining the streets to catch a glimpse of the 82-year-old pontiff. Hunched over, Su Santidad, or His Holiness, slowly made his way to a special altar set up in front of the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. That holy place, the destination of tens of millions of pilgrims throughout the years, was the setting for a very special event: the canonization of the first indigenous saint of the Americas by the aged Polish pope who was loved by all Mexican Catholics. Although his body was frail, the pope’s voice was surprisingly strong, and he read flawlessly in Spanish his prepared speech. It was his 5th visit to Mexico and by the end of the day, Mexicans had their 4th saint, officially known as San Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin.

It was a warm day in Mexico City. The date was July 31, 2002. The aged Catholic pope, John Paul the Second, arrived at the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe, after passing hundreds of thousands of people lining the streets to catch a glimpse of the 82-year-old pontiff. Hunched over, Su Santidad, or His Holiness, slowly made his way to a special altar set up in front of the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. That holy place, the destination of tens of millions of pilgrims throughout the years, was the setting for a very special event: the canonization of the first indigenous saint of the Americas by the aged Polish pope who was loved by all Mexican Catholics. Although his body was frail, the pope’s voice was surprisingly strong, and he read flawlessly in Spanish his prepared speech. It was his 5th visit to Mexico and by the end of the day, Mexicans had their 4th saint, officially known as San Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin.

So, who was Juan Diego and why did the Catholic Church make him a saint? In short, he played a crucial role in the story of the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a series of miraculous events occurring just 10 years after the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs. As all of this happened nearly 5 centuries ago, much of the story of Juan Diego’s life and times is shrouded in mystery. Some people today allege that Juan Diego never existed, and although the Catholic Church investigated his life thoroughly and people within the church still had serious doubts, after the 2002 proclamation of sainthood, according to the Vatican the case is officially closed.

The man known now as San Juan Diego was born in the year 1474 with the name Cuauhtlatoatzin, which means in Nahuatl, “Eagle Who Speaks.” According to the official story, he lived in the town of Cuautitlán which is presently located in the Mexican state of México just north of the norther tip of the Federal District. Cuautitlán, which means, “The Place Between the Trees,” was once a village of Chichimecas who had since given up their nomadic ways for a more sedentary existence. A few generations before Juan Diego’s birth the future saint’s hometown was conquered by the Kingdom of Tlacopan, whose capital city lay on the western shores of Lake Texcoco. When Tlacopan joined with the city-state of Tenochtitlán and the Kingdom of Texcoco to become what scholars call the Aztec Triple Alliance, Juan Diego’s place of birth became part of what would later be considered the Aztec Empire. By the time he was born he would live in a fully Aztec world, and he grew up speaking Nahuatl. The house in which Juan Diego lived with his wife, María Lucia, still stands in the town of Cuautitlán and today is visited by many tourists and pilgrims alike. In the early 1520s, when Juan Diego was already in his mid-40s, the Franciscans arrived in the area and started baptizing the natives. According to the story, Juan Diego and his wife were among the very first people baptized in Cuautitlán. María Lucia died in 1529. After his wife’s death Juan Diego, now in his 50s, moved to a small village near Tepeyac Hill, closer to Mexico City, and lived with his uncle Juan Bernardino. It’s important to note that just a decade before, Tepeyac was a sacred place, said to be the home of the Aztec goddess Tonantzin, an earth deity also known as “The Bringer of Corn” or “The Mother of Sustenance.”

The man known now as San Juan Diego was born in the year 1474 with the name Cuauhtlatoatzin, which means in Nahuatl, “Eagle Who Speaks.” According to the official story, he lived in the town of Cuautitlán which is presently located in the Mexican state of México just north of the norther tip of the Federal District. Cuautitlán, which means, “The Place Between the Trees,” was once a village of Chichimecas who had since given up their nomadic ways for a more sedentary existence. A few generations before Juan Diego’s birth the future saint’s hometown was conquered by the Kingdom of Tlacopan, whose capital city lay on the western shores of Lake Texcoco. When Tlacopan joined with the city-state of Tenochtitlán and the Kingdom of Texcoco to become what scholars call the Aztec Triple Alliance, Juan Diego’s place of birth became part of what would later be considered the Aztec Empire. By the time he was born he would live in a fully Aztec world, and he grew up speaking Nahuatl. The house in which Juan Diego lived with his wife, María Lucia, still stands in the town of Cuautitlán and today is visited by many tourists and pilgrims alike. In the early 1520s, when Juan Diego was already in his mid-40s, the Franciscans arrived in the area and started baptizing the natives. According to the story, Juan Diego and his wife were among the very first people baptized in Cuautitlán. María Lucia died in 1529. After his wife’s death Juan Diego, now in his 50s, moved to a small village near Tepeyac Hill, closer to Mexico City, and lived with his uncle Juan Bernardino. It’s important to note that just a decade before, Tepeyac was a sacred place, said to be the home of the Aztec goddess Tonantzin, an earth deity also known as “The Bringer of Corn” or “The Mother of Sustenance.”

On December 9, 1531, Juan Diego was walking near the hill at Tepeyac Hill on his way to Mexico City when he heard beautiful music that sounded like the singing of birds. A cloud appeared and then an image of the sun formed around what appeared to be a young woman dressed like an Aztec princess wearing a cloak full of stars. The woman spoke to Juan Diego in his own language, and told him not to be afraid. She also requested that a chapel in her honor be built on the top of the hill. Juan Diego went down into Mexico City to tell the Bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga, of what he saw and heard, which would be later referred to as the First Apparition.

The Second Apparition occurred later that day when Juan Diego returned to the hill. He told the Virgin that he had failed on his mission to the bishop, but she told him to persist. The Virgin was emphatic that a temple devoted to her must be built on that hill and that he could not fail again. Juan Diego promised to try again and then retired to his home.

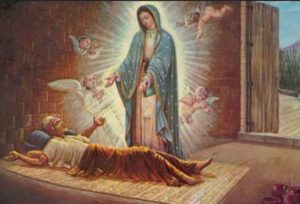

The next day Juan Diego returned to the bishop’s residence to plead with him again to do as the Lady on the hill requested. Zumárraga told Juan Diego that he needed a sign from this mysterious woman, something that would prove to him that this was Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ. When Juan Diego left, the bishop had him followed but the people following him lost track of him when he crossed a ravine. Juan Diego’s trackers went back to the bishop with no information about the hill or the mysterious woman. When Juan Diego returned to Tepeyac, the Virgin was waiting for him there. This is known as the Third Apparition. Juan Diego expressed his regret for not being able to convince the bishop for the second time and told the shimmering woman that Zumárraga requested some sort of sign to prove that what he was saying was true. The Virgin then told Juan Diego to return in the morning and she would provide him with what was needed.

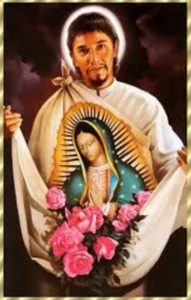

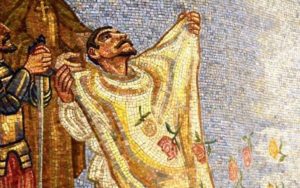

Juan Diego did not return in the morning, however. His uncle, Juan Bernardino, was very sick and Juan Diego tended to him and even arranged for a doctor’s visit. The visit to the lady on the hill was on his mind, but he couldn’t tear himself away from his family responsibilities. The following morning, Juan Bernardino was not feeling better and asked Juan Diego to go into town and get a priest to make his last confession and to absolve him of all his sins before he died. Juan Diego did as his uncle wished, but in order to go into town, he had to pass by the hill at Tepeyac. He was a little reluctant to do so because he missed his meeting time with the lady on the hill the previous morning. When Juan Diego skirted the hill the woman appeared again, behind the rays of the sun and in a cloudburst as she had done the other times. This encounter is known as the Fourth Apparition. The Virgin consoled Juan Diego and told him that there was no need for him to get a priest or any more doctors because his uncle had already been healed. On the matter of the sign to present to the bishop, the lady told Juan Diego to climb to the top of the hill and to gather the flowers at its crest. Juan Diego ascended Tepeyac Hill and was surprised to see vibrantly colored Castilian roses in full bloom at the top of the hill. This was strange because it was December and the frosts had already come and the area was desolate and devoid of flowers. Juan Diego gathered some of the beautiful dew-covered roses in his cactus-fiber cloak, known as a tilma, and went down to the heart of Mexico City to deliver this celestial sign to Bishop Zumárraga. When he got to the bishop’s palace to request an audience, the people there knew him as “the pestering Indian,” and refused to acknowledge him. When one of the guards saw that Juan Diego was carrying something bunched up in his cloak, he went towards him and saw the beautiful flowers. The guard reached in to take one, but couldn’t. The rose he tried to grab looked more like an illustration than a real flower. Convinced that Juan Diego had something of importance, the guard granted him access to the bishop. When Zumárraga asked Juan Diego what he had for him, the humble indigenous man unfurled his cloak and a variety of beautiful roses cascaded to the ground. The bishop and those present dropped to their knees, not just because of the flowers but because of the image that appeared on the front of Juan Diego’s cloak: the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the one known to reverent Catholics to this day. The church authorities removed Juan Diego’s cloak, and that same piece of cactus cloth, which should have lasted no more than 20 years, hangs now in the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe which now stands on the top of that hill at Tepeyac where the apparitions appeared.

Juan Diego did not return in the morning, however. His uncle, Juan Bernardino, was very sick and Juan Diego tended to him and even arranged for a doctor’s visit. The visit to the lady on the hill was on his mind, but he couldn’t tear himself away from his family responsibilities. The following morning, Juan Bernardino was not feeling better and asked Juan Diego to go into town and get a priest to make his last confession and to absolve him of all his sins before he died. Juan Diego did as his uncle wished, but in order to go into town, he had to pass by the hill at Tepeyac. He was a little reluctant to do so because he missed his meeting time with the lady on the hill the previous morning. When Juan Diego skirted the hill the woman appeared again, behind the rays of the sun and in a cloudburst as she had done the other times. This encounter is known as the Fourth Apparition. The Virgin consoled Juan Diego and told him that there was no need for him to get a priest or any more doctors because his uncle had already been healed. On the matter of the sign to present to the bishop, the lady told Juan Diego to climb to the top of the hill and to gather the flowers at its crest. Juan Diego ascended Tepeyac Hill and was surprised to see vibrantly colored Castilian roses in full bloom at the top of the hill. This was strange because it was December and the frosts had already come and the area was desolate and devoid of flowers. Juan Diego gathered some of the beautiful dew-covered roses in his cactus-fiber cloak, known as a tilma, and went down to the heart of Mexico City to deliver this celestial sign to Bishop Zumárraga. When he got to the bishop’s palace to request an audience, the people there knew him as “the pestering Indian,” and refused to acknowledge him. When one of the guards saw that Juan Diego was carrying something bunched up in his cloak, he went towards him and saw the beautiful flowers. The guard reached in to take one, but couldn’t. The rose he tried to grab looked more like an illustration than a real flower. Convinced that Juan Diego had something of importance, the guard granted him access to the bishop. When Zumárraga asked Juan Diego what he had for him, the humble indigenous man unfurled his cloak and a variety of beautiful roses cascaded to the ground. The bishop and those present dropped to their knees, not just because of the flowers but because of the image that appeared on the front of Juan Diego’s cloak: the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the one known to reverent Catholics to this day. The church authorities removed Juan Diego’s cloak, and that same piece of cactus cloth, which should have lasted no more than 20 years, hangs now in the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe which now stands on the top of that hill at Tepeyac where the apparitions appeared.

Soon after a small church was built on Tepeyac in 1532, masses of Indians converted to Christianity and word spread throughout New Spain of the miraculous apparitions, the curing of Juan Diego’s uncle, and the beautiful roses that served as the sign from Heaven. Critics claim that the whole story was made up and that the image is a fake. The fact that the “lady on the hill” appeared in a place that had been connected to a former Aztec goddess, that the woman supposedly spoke the Indian language and looked like a Native has some people wondering if this wasn’t an elaborate trick to make the process of conquest easier. To the world’s billion or so Catholics, there is no doubt that the Mother of God, the “mother of us all” appeared to a humble servant that day on a hill in Mexico.

Soon after a small church was built on Tepeyac in 1532, masses of Indians converted to Christianity and word spread throughout New Spain of the miraculous apparitions, the curing of Juan Diego’s uncle, and the beautiful roses that served as the sign from Heaven. Critics claim that the whole story was made up and that the image is a fake. The fact that the “lady on the hill” appeared in a place that had been connected to a former Aztec goddess, that the woman supposedly spoke the Indian language and looked like a Native has some people wondering if this wasn’t an elaborate trick to make the process of conquest easier. To the world’s billion or so Catholics, there is no doubt that the Mother of God, the “mother of us all” appeared to a humble servant that day on a hill in Mexico.

In 1984 the Archbishop of Mexico, Ernesto Corripio Ahumada, appointed a Postulator to start an inquiry to initiate the formal process to make Juan Diego a saint. The making of a Catholic saint is a lengthy and complicated procedure. The saintly candidate goes through many stages. Juan Diego was pronounced “venerable” on January 9, 1987. He was moved to the level of “beatified” by Pope John Paul the Second on May 6, 1990, during the pontiff’s second visit to Mexico. To make it to the “beatified” stage, a prospective saint must have a miracle attributed to him or her. The Vatican overlooked this detail stating that since Juan Diego had been revered by Mexicans for so long, the investigation into miracles was unnecessary. A miracle connected to Juan Diego involving the survival of a drug addict who tried to commit suicide in Querétaro was later investigated and confirmed which led the pope to put Juan Diego on a list for canonization in December of 2001. The next year, 2002, the aged pontiff arrived in Mexico City for the formal sainthood ceremonies and it was one of the most popular visits of the 100+ foreign trips that John Paul made during his nearly 27 years as pope. With his canonization, interest in San Juan Diego grew and many more miracles have been attributed to him since. While some may debate this man’s very existence, no one doubts the enormous faith San Juan Diego continues to generate among true believers.

REFERENCES

Chavez, Eduardo. Our Lady of Guadalupe and Saint Juan Diego: The Historical Evidence. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006. We are Amazon affiliates. Purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3D9b9FS