Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

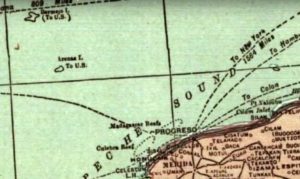

On the Mexico-Querétaro Highway, on August 4, 1998, a semi-truck slammed into the side of a car carrying two passengers. One, the driver, was unharmed. The other person in the car was killed instantly. The passenger was the 74-year-old José Ángel Conchello Dávila, a Mexican senator and former head of the Mexican political party known as the PAN. While holding many offices and posts in his long and distinguished political career, Senator Conchello was perhaps best known for what otherwise would have amounted to a footnote to history: He was a tireless defender of the existence of Isla Bermeja, a small island about 100 kilometers off the coast of the Yucatán which had appeared on maps off and on across the centuries and in recent times had not been confirmed as real. Conchello reasoned that if the island were proven real, it would extend Mexico’s maritime territorial claims much farther into the Gulf of Mexico and would secure Mexico’s rights to billions of barrels of petroleum and untold mineral resources within an expanded Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ, of Mexico. Senator Conchello advocated rediscovering the island, building a lighthouse or some other improvements there and establishing a permanent Mexican presence on Bermeja all the while Mexico was negotiating with the United States on how the two countries would divvy up the Gulf of Mexico’s resources. In September of 1997, the Secretary of the Navy of the Mexican government sent an oceanographic vessel to try to locate the island, covering over 300 square nautical miles in the general area of where Isla Bermeja had appeared on various maps. They found nothing. Senator Conchello accused the United States, specifically the CIA, of deliberately destroying the island so as to nullify any larger claims Mexico would have in the Gulf. Months before senator’s voice was permanently silenced in that fatal car crash in 1998, the US and Mexico signed the Clinton-Zedillo Treaty, which was heavily influenced by big American oil companies, and the partitioning of the Gulf of Mexico into economic zones was complete. The Clinton-Zedillo Treaty ignored the possible existence of Isla Bermeja and thus awarded the United States a lion’s share of the resources of the region.

On the Mexico-Querétaro Highway, on August 4, 1998, a semi-truck slammed into the side of a car carrying two passengers. One, the driver, was unharmed. The other person in the car was killed instantly. The passenger was the 74-year-old José Ángel Conchello Dávila, a Mexican senator and former head of the Mexican political party known as the PAN. While holding many offices and posts in his long and distinguished political career, Senator Conchello was perhaps best known for what otherwise would have amounted to a footnote to history: He was a tireless defender of the existence of Isla Bermeja, a small island about 100 kilometers off the coast of the Yucatán which had appeared on maps off and on across the centuries and in recent times had not been confirmed as real. Conchello reasoned that if the island were proven real, it would extend Mexico’s maritime territorial claims much farther into the Gulf of Mexico and would secure Mexico’s rights to billions of barrels of petroleum and untold mineral resources within an expanded Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ, of Mexico. Senator Conchello advocated rediscovering the island, building a lighthouse or some other improvements there and establishing a permanent Mexican presence on Bermeja all the while Mexico was negotiating with the United States on how the two countries would divvy up the Gulf of Mexico’s resources. In September of 1997, the Secretary of the Navy of the Mexican government sent an oceanographic vessel to try to locate the island, covering over 300 square nautical miles in the general area of where Isla Bermeja had appeared on various maps. They found nothing. Senator Conchello accused the United States, specifically the CIA, of deliberately destroying the island so as to nullify any larger claims Mexico would have in the Gulf. Months before senator’s voice was permanently silenced in that fatal car crash in 1998, the US and Mexico signed the Clinton-Zedillo Treaty, which was heavily influenced by big American oil companies, and the partitioning of the Gulf of Mexico into economic zones was complete. The Clinton-Zedillo Treaty ignored the possible existence of Isla Bermeja and thus awarded the United States a lion’s share of the resources of the region.

Is the island called Isla Bermeja a real place? Was it once real and now gone? Was it something misdescribed or was it reported to be in the wrong place? The search for truth begins in Florence, Italy, at the Archivo di Stato. In these archives there exists a map dating back to 1535, drawn by Gaspar Viegas, a Portuguese cartographer. On the map there is clear indication that an island exists in the Gulf of Mexico called Bermeja, which in older Iberian dialects means “reddish in color.” The English word “vermilion” comes from the same Latin root as “bermeja.” On this map and others, the island was supposedly located at 22 degrees, 33 minutes north latitude and 91 degrees, 22 minutes west longitude. Bermeja next appears in a 1544 map by Sebastian Cabot, the Italian explorer who sailed for England and charted many areas of North America. The map was printed in Antwerp and clearly shows Bermeja along with a small group of islands to the east of it called Negrillos. Over the centuries, like Isla Bermeja, the series of about 6 small coral islets and rocks known as Negrillos will appear and disappear, and to this day the existence of this small chain of islands is also in dispute. Cabot’s map was especially useful for his English overlords who encouraged piracy in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. As a consequence, Isla Bermeja was also known as a hiding place for English and Dutch buccaneers who would attack Spanish treasure ships and disrupt commerce in the area. At this time, it had been described as a lightly wooded island measuring roughly 80 square kilometers and with abundant bird life. The island first “disappears” in 1772. In a comprehensive map of New Spain by Alzate and Ramirez neither Bermeja nor the tiny islands of Negrillos are present. A few years after the publication of this map, official cartographers of the Spanish Crown, Miguel de Alderete and Andrés Valderrama, sought to prove the existence of islands rumored to be north of the Yucatán and hundreds of miles into the Gulf. From Alderete’s diary of July of 1775, he writes:

Is the island called Isla Bermeja a real place? Was it once real and now gone? Was it something misdescribed or was it reported to be in the wrong place? The search for truth begins in Florence, Italy, at the Archivo di Stato. In these archives there exists a map dating back to 1535, drawn by Gaspar Viegas, a Portuguese cartographer. On the map there is clear indication that an island exists in the Gulf of Mexico called Bermeja, which in older Iberian dialects means “reddish in color.” The English word “vermilion” comes from the same Latin root as “bermeja.” On this map and others, the island was supposedly located at 22 degrees, 33 minutes north latitude and 91 degrees, 22 minutes west longitude. Bermeja next appears in a 1544 map by Sebastian Cabot, the Italian explorer who sailed for England and charted many areas of North America. The map was printed in Antwerp and clearly shows Bermeja along with a small group of islands to the east of it called Negrillos. Over the centuries, like Isla Bermeja, the series of about 6 small coral islets and rocks known as Negrillos will appear and disappear, and to this day the existence of this small chain of islands is also in dispute. Cabot’s map was especially useful for his English overlords who encouraged piracy in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. As a consequence, Isla Bermeja was also known as a hiding place for English and Dutch buccaneers who would attack Spanish treasure ships and disrupt commerce in the area. At this time, it had been described as a lightly wooded island measuring roughly 80 square kilometers and with abundant bird life. The island first “disappears” in 1772. In a comprehensive map of New Spain by Alzate and Ramirez neither Bermeja nor the tiny islands of Negrillos are present. A few years after the publication of this map, official cartographers of the Spanish Crown, Miguel de Alderete and Andrés Valderrama, sought to prove the existence of islands rumored to be north of the Yucatán and hundreds of miles into the Gulf. From Alderete’s diary of July of 1775, he writes:

“We sailed for Havana trying to locate Bermeja and other islands. When we arrived at the location of Bermeja even though the visibility was clear and the sea calm, we didn’t discover anything, not a spot, nor a mark, nor variance in color, nothing.”

A few decades later, in another journey from Veracruz to Havana, the captains of the ships San Julian and the Buen Consejo, two men named Juan Moreno and Manuel Sandoval, respectively, reported the sighting of a large rock jutting out of the water east of where the maps put Isla Bermeja. The captains, and later researchers, determined this rock to be part of the Negrillos group, and somehow, although nearby, they had completely missed Bermeja. Reports like these were not uncommon in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

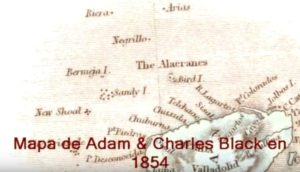

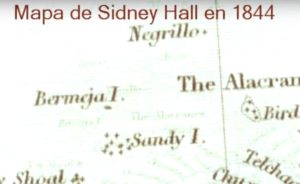

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Isla Bermeja was repeatedly shown on maps that were official or edited by or under the supervision of the Mexican government, but no maritime verification was known to have been carried out in the region during this time. The existence of the island is registered in the 1864 Ethnographic Charter of Mexico, governmental edition, and also in a book from that time called Islas Mexicanas officially published by the Secretariat of Public Education. On page 110 the book places the island at 22º 33’ North latitude, and 91º 22′ West. Some American and English maps of the 1800s not only showed the existence of Isla Bermeja and the similarly on-again, off-again Negrillos chain, they showed them as being territory of the United States, with a small “U.S” in parentheses under the name of the islands on maps. This was not uncommon to see, as many unclaimed or out-of-the-way small islands, reefs and atolls were claimed by the United States under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The first part of the act reads:

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Isla Bermeja was repeatedly shown on maps that were official or edited by or under the supervision of the Mexican government, but no maritime verification was known to have been carried out in the region during this time. The existence of the island is registered in the 1864 Ethnographic Charter of Mexico, governmental edition, and also in a book from that time called Islas Mexicanas officially published by the Secretariat of Public Education. On page 110 the book places the island at 22º 33’ North latitude, and 91º 22′ West. Some American and English maps of the 1800s not only showed the existence of Isla Bermeja and the similarly on-again, off-again Negrillos chain, they showed them as being territory of the United States, with a small “U.S” in parentheses under the name of the islands on maps. This was not uncommon to see, as many unclaimed or out-of-the-way small islands, reefs and atolls were claimed by the United States under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The first part of the act reads:

“Whenever any citizen of the United States discovers a deposit of guano on any island, rock, or key, not within the lawful jurisdiction of any other Government, and not occupied by the citizens of any other Government, and takes peaceable possession thereof, and occupies the same, such island, rock, or key may, at the discretion of the President, be considered as appertaining to the United States.”

Whether any American ever visited Bermeja or Negrillos and made territorial claims is not known. Cartographers may have just been following a convention of labeling any remote islands and rocks as being possessions of the United States.

By the 1920s Isla Bermeja had disappeared from most maps. Officials from Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs even declared before the Mexican Congress that the island had sunk and no longer existed. A Mexican senator at the time, Luis Coppola Joffroy, made statements to the media about the Foreign Affairs Ministry’s presentation to Congress. He said:

“Although since the sixteenth century the state of Yucatan was included as part of national and international maps, since 1920 (Isla Bermeja) is no longer taken into account as Mexican national territory, and at present, physically, its information is not found or hidden by different authorities and governmental entities.”

The last government-printed schoolbook showing Isla Bermeja was released in 1946. After that, interest in the island disappeared, it seems, along with the island.

It was only during the Clinton Administration in the United States during the 1990s when Mexican national attention focused once again on Isla Bermeja on the insistence of Senator Conchello. With the Clinton-Zedillo Treaty in force for over a decade, and with American oil companies already well established with gigantic platforms in the Gulf on agreed-to territory, interest in Isla Bermeja resurfaced, much like an island rising out of the sea. In 2009 there were 3 formal expeditions to find the island.

On March 20, 2009, the oceanographic vessel Justo Sierra of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, sailed from the port of Tuxpan, Veracruz, to conduct an on-site study. This vessel was equipped with the most modern scientific devices for marine research. The results of this expedition that were published in the UNAM Gazette of June 25, 2009, indicate that, “There are no vestiges of an island in the area studied.” It also points out that, “at the point of interest the sea has a depth of 1472 meters and is on a flat bottom.” The UNAM expedition did not rule out that the vestiges of the island are in different coordinates or if the island had existed in the past. Its disappearance could have been explained by geological forces causing it to sink.

On March 20, 2009, the oceanographic vessel Justo Sierra of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, sailed from the port of Tuxpan, Veracruz, to conduct an on-site study. This vessel was equipped with the most modern scientific devices for marine research. The results of this expedition that were published in the UNAM Gazette of June 25, 2009, indicate that, “There are no vestiges of an island in the area studied.” It also points out that, “at the point of interest the sea has a depth of 1472 meters and is on a flat bottom.” The UNAM expedition did not rule out that the vestiges of the island are in different coordinates or if the island had existed in the past. Its disappearance could have been explained by geological forces causing it to sink.

The second expedition was carried out between May 25 to June 1 of the same year, by the Mexican Navy vessel Rio Tuxpan, and was sponsored by the Mexican Society of Geography and Statistics. Although a definitive and official version of this expedition is not available, information was made public through the interviews published in the Diario de Yucatán and the notes published by the expedition participant Edwin Corona. The expedition’s mission was simple: “To clear up doubts and make known the whereabouts of the Bermeja Island.” The Rio Tuxpan traveled 1,500 kilometers and did not just inspect the island’s assumed coordinates but also explored much of the surrounding waters. This expedition found nothing and concluded that the existence of Isla Bermeja and of the small chain of islands called Negrillos was simple cartographic error repeated over time.

The third expedition was financed by Televisión Azteca. The ship Kalin Haa set sail on June 5, 2009, with several researchers on board, among them the historian and cartographer, a specialist in cartography of the Yucatan Peninsula, Michel Antochiw Kolpa. Although this trip was made in more precarious conditions than the previous two, from the point of view of the technical equipment available on board, the conclusions were similar. Antochiw stated, “La Bermeja is not the only ‘disappeared’ island. The small archipelago called in the old maps Negrillos Islands, or the Reef of Negrillo, does not exist, nor do the other keys or reefs such as the so-called Arias Bank.”

The third expedition was financed by Televisión Azteca. The ship Kalin Haa set sail on June 5, 2009, with several researchers on board, among them the historian and cartographer, a specialist in cartography of the Yucatan Peninsula, Michel Antochiw Kolpa. Although this trip was made in more precarious conditions than the previous two, from the point of view of the technical equipment available on board, the conclusions were similar. Antochiw stated, “La Bermeja is not the only ‘disappeared’ island. The small archipelago called in the old maps Negrillos Islands, or the Reef of Negrillo, does not exist, nor do the other keys or reefs such as the so-called Arias Bank.”

In addition to the sea expeditions, there have been attempts to locate the island by air and satellite. One notable attempt to locate the island by air was made by the Mexican television network Televisa which created a show about Isla Bermeja that considered the island to be a mystery along the lines of The Bermuda Triangle. Indeed, others have noted the existence of ley lines crossing the path of the island or mysterious vortexes nearby that may cause the island to pop in and out of existence. If the island once existed and indeed is now gone, there are many theories to explain its disappearance, from rising sea levels due to global warming, to destruction by hurricanes or other natural forces, to Senator Conchello’s theories about CIA obliteration of a tiny piece of very valuable Mexican territory.

The story of Isla Bermeja is not over. On April 4, 2012 a man named Marco Antonio Salvo Veloso uploaded a five-and-a-half-minute video to YouTube about a fishing trip that he and his two friends took to Isla Bermeja. The island has the reddish tones, ample birds and scrubby trees that were described in the 16th Century Spanish and pirate accounts. There were no compass coordinates accompanying the video, so there is no way of telling exactly where Salvo Veloso actually was, but it seems like it wasn’t his first trip out to this island. Whether real or imagined, sunk or destroyed, caught between vortexes or blinking out of space and time, Isla Bermeja remains a little-known but intriguing Mexican mystery.

REFERENCES

Breglia, Lisa. Living with Oil: Promises, Peaks, and Declines on Mexico’s Gulf Coast. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013.

Casares Cámara, Hernán. “Confirman la inmersión de una isla.” In Diario de Yucatán, 26 Nov. 2008. (in Spanish)

Dirección Hidrográfica. Derrotero de las islas Antillas: de las costas de Tierra Firme. Madrid: Imprenta Nacional, 1820. (in Spanish)

Méndez, Enrique and Robert Garduño. “No encuentran la Isla Bermeja.” La Jornada, 24 Jun 2009. (in Spanish)

3 thoughts on “Isla Bermeja, Mexico’s Disappearing Island”

Robert Bitto, thanks so much for the post.Really thank you! Keep writing.cheap custom essays

So interesting, with far more details than any other source I’ve found on the subject. Thank you so much!

I’m glad you found it helpful. Thanks for stopping by.