Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, one of the first Europeans to explore the eastern Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, arrived ashore in March of 1517. He was not alone but came with over 100 disgruntled Spanish settlers from Cuba. Hernández de Córdoba noted that on the island of Cozumel – known by the Maya as Kùutsmil – there was a shrine to the Maya moon goddess Ix-Chel. A priest would sit inside of a statue and give oracles to the women who would travel there to ask for blessings and advice regarding marriage and childbirth. Ix-Chel was usually represented as having a snake on her head and a skirt decorated in a crossbones pattern. Often times she was depicted as having claws for hands and feet and she was associated with jaguars, a very old animal symbol in ancient Mexico. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba also noticed that the small island north of Cozumel served as some sort of secondary pilgrimage site for the moon goddess and he found it littered in small statues and figurines, and other representations of Ix-Chel. The name Hernández de Córdoba gave to that small island to this day still bears the name he gave it: Isla Mujeres, or in English, The Island of Women. In the local Maya dialect, Ix-Chel literally meant, “Lady Rainbow,” and in addition to being the moon goddess, she had other aspects and functions. In the book written by the Archbishop of the Yucatán, Diego de Landa called Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English The List of Things in the Yucatán, the moon goddess Ix-Chel was associated with medicine, and according to de Landa in the month the Maya called Zip the Maya celebrated the feast of Ihcil Ix-Chel which honored physicians and shamans and included rituals involving divination stones and medicine bundles. De Landa also mentions that during what is called the “Ritual of the Bacabs,” the moon goddess is also referred to “grandmother.” In another Spanish source, the 16th Century historian and Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas relates a story of Ix-Chel and her husband Itzamna created the heaven and the earth, and together had 13 sons.

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, one of the first Europeans to explore the eastern Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, arrived ashore in March of 1517. He was not alone but came with over 100 disgruntled Spanish settlers from Cuba. Hernández de Córdoba noted that on the island of Cozumel – known by the Maya as Kùutsmil – there was a shrine to the Maya moon goddess Ix-Chel. A priest would sit inside of a statue and give oracles to the women who would travel there to ask for blessings and advice regarding marriage and childbirth. Ix-Chel was usually represented as having a snake on her head and a skirt decorated in a crossbones pattern. Often times she was depicted as having claws for hands and feet and she was associated with jaguars, a very old animal symbol in ancient Mexico. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba also noticed that the small island north of Cozumel served as some sort of secondary pilgrimage site for the moon goddess and he found it littered in small statues and figurines, and other representations of Ix-Chel. The name Hernández de Córdoba gave to that small island to this day still bears the name he gave it: Isla Mujeres, or in English, The Island of Women. In the local Maya dialect, Ix-Chel literally meant, “Lady Rainbow,” and in addition to being the moon goddess, she had other aspects and functions. In the book written by the Archbishop of the Yucatán, Diego de Landa called Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English The List of Things in the Yucatán, the moon goddess Ix-Chel was associated with medicine, and according to de Landa in the month the Maya called Zip the Maya celebrated the feast of Ihcil Ix-Chel which honored physicians and shamans and included rituals involving divination stones and medicine bundles. De Landa also mentions that during what is called the “Ritual of the Bacabs,” the moon goddess is also referred to “grandmother.” In another Spanish source, the 16th Century historian and Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas relates a story of Ix-Chel and her husband Itzamna created the heaven and the earth, and together had 13 sons.

It’s important to note that much of what researchers know about the old Maya gods has come to the present day in pieces and this is still a field of active research. The complete picture of the Mayan pantheon, or collection of gods, is still somewhat murky. Many gods and goddesses had different overlapping functions and exhibited great variety across place and time. In the case of Ix-Chel, for example, what we know about her comes from 16th Century accounts of the Maya who were living almost 5 centuries after Classic Maya civilization collapsed. When people like Diego de Landa and Francisco Hernández de Córdoba encountered this jaguar-looking moon goddess, they were looking at this deity in a fixed time and place. What this jaguar goddess meant to the ancient Maya is not completely known and researchers are not sure of her meaning across the various city states found throughout the Maya world. As researchers start to piece together the great number of Maya gods, they are seeing that this collection of deities is less like the old Greek gods and more like the modern-day collection of Catholic saints. When the average person does a quick internet lookup of the old Maya gods, most people want them to be carefully indexed and described like one would find for the gods of ancient Greece. Who is the ancient Greek god of the oceans? Simple: Poseidon. Who is the goddess of agriculture? Demeter, and so on. A simple, clean table like that for the Maya does not exist. As previously alluded to, although not a perfect comparison by any means, the Maya gods are a lot like the Catholic saints. They are expressions of the divine, there are many of them taking care of many different functions and some of those functions overlap. Like the Catholic saints, some of them vary by region, they are worshipped differently by different people and have different artistic representations. Modern-day researchers have tried to classify the ancient Mexican deities by appearance, function, place and what they are associated with. The story of the ancient Maya continues to be written and it will be a long time, if ever, before we get a complete picture of ancient Maya life and culture. Religion seems to be a very tricky element of this culture to understand. Take, for example, the gods associated with the jaguar. They go way beyond the 16th Century Maya moon goddess and her feminine catlike qualities.

It’s important to note that much of what researchers know about the old Maya gods has come to the present day in pieces and this is still a field of active research. The complete picture of the Mayan pantheon, or collection of gods, is still somewhat murky. Many gods and goddesses had different overlapping functions and exhibited great variety across place and time. In the case of Ix-Chel, for example, what we know about her comes from 16th Century accounts of the Maya who were living almost 5 centuries after Classic Maya civilization collapsed. When people like Diego de Landa and Francisco Hernández de Córdoba encountered this jaguar-looking moon goddess, they were looking at this deity in a fixed time and place. What this jaguar goddess meant to the ancient Maya is not completely known and researchers are not sure of her meaning across the various city states found throughout the Maya world. As researchers start to piece together the great number of Maya gods, they are seeing that this collection of deities is less like the old Greek gods and more like the modern-day collection of Catholic saints. When the average person does a quick internet lookup of the old Maya gods, most people want them to be carefully indexed and described like one would find for the gods of ancient Greece. Who is the ancient Greek god of the oceans? Simple: Poseidon. Who is the goddess of agriculture? Demeter, and so on. A simple, clean table like that for the Maya does not exist. As previously alluded to, although not a perfect comparison by any means, the Maya gods are a lot like the Catholic saints. They are expressions of the divine, there are many of them taking care of many different functions and some of those functions overlap. Like the Catholic saints, some of them vary by region, they are worshipped differently by different people and have different artistic representations. Modern-day researchers have tried to classify the ancient Mexican deities by appearance, function, place and what they are associated with. The story of the ancient Maya continues to be written and it will be a long time, if ever, before we get a complete picture of ancient Maya life and culture. Religion seems to be a very tricky element of this culture to understand. Take, for example, the gods associated with the jaguar. They go way beyond the 16th Century Maya moon goddess and her feminine catlike qualities.

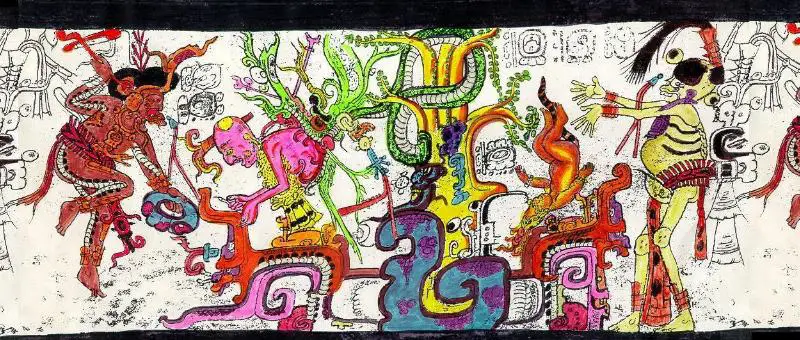

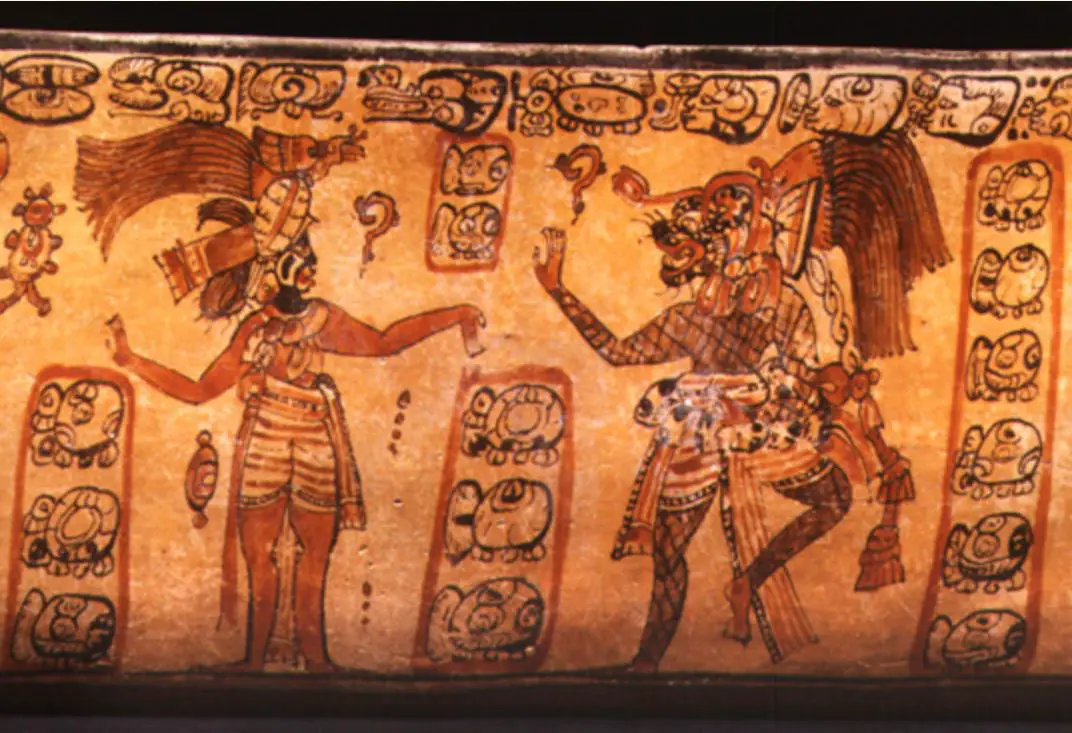

Because the classical ancient Maya civilization was long gone by the time the Spanish arrived, hard-core scholars and assorted researchers have little to go on to try to put together a story of the full range of Maya gods. Most of what is known today about the gods comes from representations in Maya art, and from what little investigators can glean from the hieroglyphic writing the ancient Maya left behind. The art ranges from beautifully painted murals to illustrations found on pottery, and from beautiful stone carvings to the scant few Maya books that survived colonial book burnings. Maya research is an exciting field in that new discoveries are made on a weekly basis and each new discovery adds to the knowledge of these fascinating people. From what is known now, the jaguar has always been an important symbol throughout ancient Mexico across time, cultures, and geographical regions. As an apex predator of the Mexican forests and jungles, the jaguar evokes a sense of mystery and power, even to this day. In the Maya area, gods exhibiting jaguar features and qualities have a special place among the ancient pantheon.

Because the classical ancient Maya civilization was long gone by the time the Spanish arrived, hard-core scholars and assorted researchers have little to go on to try to put together a story of the full range of Maya gods. Most of what is known today about the gods comes from representations in Maya art, and from what little investigators can glean from the hieroglyphic writing the ancient Maya left behind. The art ranges from beautifully painted murals to illustrations found on pottery, and from beautiful stone carvings to the scant few Maya books that survived colonial book burnings. Maya research is an exciting field in that new discoveries are made on a weekly basis and each new discovery adds to the knowledge of these fascinating people. From what is known now, the jaguar has always been an important symbol throughout ancient Mexico across time, cultures, and geographical regions. As an apex predator of the Mexican forests and jungles, the jaguar evokes a sense of mystery and power, even to this day. In the Maya area, gods exhibiting jaguar features and qualities have a special place among the ancient pantheon.

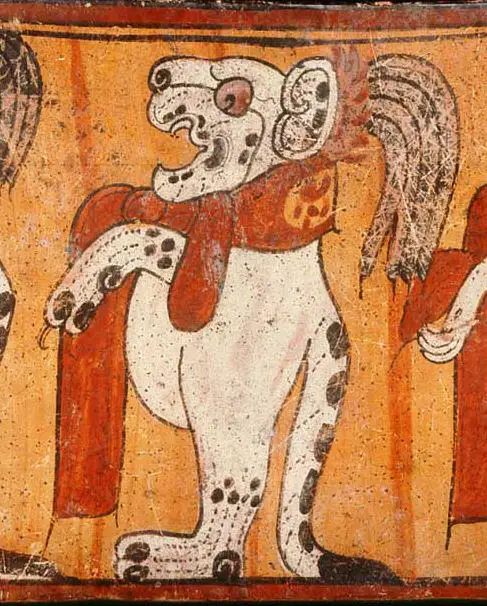

One of the oldest gods of the ancient Maya known to exhibit the qualities and attributes of the jungle cat is the deity known as God L. In the early part of the 20th Century, the ancient gods of the Maya were classified in a lettering system known as the Schellhas-Zimmermann-Taube Classification. Since the time of this god’s classification, scholars have successfully decoded the main name glyph above God L in a Maya bark-paper book called the Dresden Codex. The glyph consists of a drawing of an aged man painted in black. This may have been pronounced Ek Chuah. There is great debate as to this old god’s real name, but he is always depicted with jaguar traits, notably feline ears and a cape or mantle made out of jaguar pelts. Sometimes he has a long tail and has an owl on the top of his head. In his various depictions across the Maya world God L has been associated with three distinct functions. The owl on his head indicates an association with warfare and violence. In some parts of the Maya world God L could have been worshipped as a major war god. On a painted vase in a collection at Princeton University, he is shown decapitating bound captives in front of a jaguar palace. In the Dresden Codex God L spears his enemies. Another distinct function of this god has to do with his association with sorcery or shamanism. Researchers point to his owl headpiece and the jaguar symbolism as being connections to the underworld and the night and compare these attributes to similar gods in different parts of Mesoamerica, such as the Aztec “Man-Owl” god of sorcery. God L is sometimes depicted as smoking a cigar, which also points to shamanism and divination. Because this god is also found carrying a bundle and a fancy walking stick, some researchers believe that he is probably connected somehow to wealth and commerce. Artistic examples exist of God L depicted among maize plants and cacao trees which symbolize abundance. At the grand Maya city of Palenque, in a carving on the side of the Temple of the Sun, God L is shown with another jaguar deity, one commonly referred to by scholars as the Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire.

Associated with the number seven and the Maya day of the week called Ak’b’al, the Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire is easily recognizable throughout ancient Mayan art. This deity has very distinct jaguar features: catlike ears, fangs, and an eye shape reminiscent of the great forest predator. He has a twisted rope pattern on his face, usually surrounding his eyes. This cord is associated with the string used in making a fire with a stick. This god is also depicted on many clay incense burners in his association with fire. He has also been called the Jaguar God of the Underworld because in some artistic representations he is shown as the Night Sun, a form of the sun as it travels under the earth at night. In some cases, the Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire is depicted as a star or is associated with a constellation or planet. He is shown on one decorated vase as being attacked by a group of people bearing torches who captured him want to set him on fire. Even though in a submissive position on that specific piece of art, this god is often depicted on the shields of Maya warriors and so may also be associated with warfare. Scholars do not know what to make of this jaguar deity’s multiple functions and varied appearances across time and place. The Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire may have been many things to many people

Associated with the number seven and the Maya day of the week called Ak’b’al, the Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire is easily recognizable throughout ancient Mayan art. This deity has very distinct jaguar features: catlike ears, fangs, and an eye shape reminiscent of the great forest predator. He has a twisted rope pattern on his face, usually surrounding his eyes. This cord is associated with the string used in making a fire with a stick. This god is also depicted on many clay incense burners in his association with fire. He has also been called the Jaguar God of the Underworld because in some artistic representations he is shown as the Night Sun, a form of the sun as it travels under the earth at night. In some cases, the Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire is depicted as a star or is associated with a constellation or planet. He is shown on one decorated vase as being attacked by a group of people bearing torches who captured him want to set him on fire. Even though in a submissive position on that specific piece of art, this god is often depicted on the shields of Maya warriors and so may also be associated with warfare. Scholars do not know what to make of this jaguar deity’s multiple functions and varied appearances across time and place. The Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire may have been many things to many people

In addition to the main gods called God L and The Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire, there were other minor gods with jaguar qualities and attributes that are still subjects of curiosity and debate among even the most die-hard Maya researchers. Some of these gods may be localized spirits or elevated spirits of deceased ancestors; it is unclear. In a series of pottery pieces dating to around 700 AD a scene involving a baby jaguar is often repeated. Whether god or important spirit, Baby Jaguar is often associated in these scenes with the god of rain and the god of death. The scene occurs between sunrise and sunset and the death god is shown throwing Baby Jaguar to a mountain. In some pottery representations the rain god opens up the underworld for Baby Jaguar or is trying to cut off his head. There are a few interpretations of these scenes. Some researchers believe that Baby Jaguar must be sacrificed for something new to take his place. Others believe that Baby Jaguar doesn’t represent a spirit or god at all, but rather is symbolic and represents what a royal male child must do to become king.

Some other minor jaguar gods or powerful spirits include what archaeologists call the jaguar protectors and jaguar transformers. These supernatural beings have been seen infrequently in Maya art and some believe these are tied to important ancestors. Another infrequently seen image is that of the so-called Aged Jaguar Paddler. This god or spirit is seen in a canoe with the maize god and wears an elaborate jaguar headdress. He is associated with the night and may be linked to the Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire.

The jaguar has been a powerful symbol to the ancient Mexicans for thousands of years. The Maya, specifically, had many jaguar gods and spirits which played important roles in their formal religion and informal spiritual beliefs. Although still wrapped in mystery, the stories of these supernatural jaguar entities are becoming clearer with new interpretations and new discoveries giving modern people a more complete understanding of the world of the enigmatic Maya.

REFERENCES

Coe, Michael. The Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1993. We are an Amazon affiliate. Purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3h5DT8c

Gillespie, Susan D. and Rosemary A. Joyce. “Deity Relationships in Mesoamerican Cosmologies: The Case for the Maya God L.” In, Ancient Mesoamerica, 1998, pp. 279-296.

Morley, Sylvanus G. The Ancient Maya. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1956. We are an Amazon affiliate. Purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2XHV4oy

Sugiyama, Nawa, “Towards an Iconographic Concordance in Mesoamerican Art.” In, ICFA Dumbarton Oaks, 23 Jun 2014.

Thanks to Justin Kerr of the Maya Vase Database for the great photos!