The date was July 4, 1831. On the sprawling Hacienda de San Marcos in the central Mexican state of Aguascalientes, a baby boy was born. The boy was the son of a common laborer on the hacienda’s land, a woman named Ignacia Chávez. Ignacia’s family welcomed the baby boy even though Ignacia had no husband. The boy’s father was the wealthy Don Juan Dávalos of the neighboring Hacienda de Peñuelas. Ignacia named the boy Juan in honor of his father but because he was what was termed at the time as a “natural” child, baby Juan could not inherit his real father’s name or any of the wealth associated with being a Dávalos by blood. The young Juan Chávez would grow up on the neighboring hacienda forever feeling frustrated that he could not partake in a life he felt he should have had living in the opulent ranch house and having command over land and laborers. Instead, the life that Juan imagined he should have had was lived by his half-brother Romualdo Dávalos whom Juan often saw riding his horse on the hacienda lands like a young prince. Juan’s frustrations and his feelings of thwarted greatness made thoughts of being a hacienda laborer unbearable to him by the time he was an adolescent. Sometime in his late teens, Juan Chávez took up with a small band of miscreants and left the ranchlands for a life as a petty highwayman, robbing travelers throughout the state of Aguascalientes and into the neighboring states of Jalisco and Zacatecas.

The date was July 4, 1831. On the sprawling Hacienda de San Marcos in the central Mexican state of Aguascalientes, a baby boy was born. The boy was the son of a common laborer on the hacienda’s land, a woman named Ignacia Chávez. Ignacia’s family welcomed the baby boy even though Ignacia had no husband. The boy’s father was the wealthy Don Juan Dávalos of the neighboring Hacienda de Peñuelas. Ignacia named the boy Juan in honor of his father but because he was what was termed at the time as a “natural” child, baby Juan could not inherit his real father’s name or any of the wealth associated with being a Dávalos by blood. The young Juan Chávez would grow up on the neighboring hacienda forever feeling frustrated that he could not partake in a life he felt he should have had living in the opulent ranch house and having command over land and laborers. Instead, the life that Juan imagined he should have had was lived by his half-brother Romualdo Dávalos whom Juan often saw riding his horse on the hacienda lands like a young prince. Juan’s frustrations and his feelings of thwarted greatness made thoughts of being a hacienda laborer unbearable to him by the time he was an adolescent. Sometime in his late teens, Juan Chávez took up with a small band of miscreants and left the ranchlands for a life as a petty highwayman, robbing travelers throughout the state of Aguascalientes and into the neighboring states of Jalisco and Zacatecas.

By his early 20s Juan Chávez was well on his way to becoming a legend in central Mexico. He had teamed up with other local legends, Dionisio Pérez and the Spanish-born Máximo González, and with these two Chávez’ raids became more daring and bolder. His band of outlaws started looting businesses and homes of towns in broad daylight, not restricting their activities to small farms or rural back roads. The Chávez bandits even rode into the capital of the state, also called Aguascalientes, and burned down the municipal archives in 1862. By the early 1860s the downtrodden and poor people of the state began to look up to Chávez and admired him for trying to upset the status quo by going after high profile targets among the government and the wealthy elite. Juan Chávez had a keen knack for evading justice and had spent well over a decade successfully dodging local and federal authorities. Around campfires throughout central Mexico, people began telling stories about him and sang songs to this clever outlaw. The many legends of Juan Chávez and corridos sung about his exploits survive to this day not only in Aguascalientes but into the broader Mexican national culture. The press at the time had two nicknames for him: “Ídolo de las Beatas” or “Rojas de los mochos.” The first nickname, “Ídolo de las Beatas,“ or “Idol of the Blessed Ones,” in English, came from his rejection of government reforms restricting the power of the Church in Mexico. The second nickname, “Rojas de los mochos” has no easy translation into 21st Century English and may loosely refer to the bloody end of a butt of a rifle. The liberal press at the time painted Juan Chávez as a conservative which he was. The legendary bandit seemed more aligned with the political beliefs of his natural father, the hacienda owner Juan Dávalos, and the landed gentry of the area which disliked ever-increasing control from the central government in Mexico City.

By his early 20s Juan Chávez was well on his way to becoming a legend in central Mexico. He had teamed up with other local legends, Dionisio Pérez and the Spanish-born Máximo González, and with these two Chávez’ raids became more daring and bolder. His band of outlaws started looting businesses and homes of towns in broad daylight, not restricting their activities to small farms or rural back roads. The Chávez bandits even rode into the capital of the state, also called Aguascalientes, and burned down the municipal archives in 1862. By the early 1860s the downtrodden and poor people of the state began to look up to Chávez and admired him for trying to upset the status quo by going after high profile targets among the government and the wealthy elite. Juan Chávez had a keen knack for evading justice and had spent well over a decade successfully dodging local and federal authorities. Around campfires throughout central Mexico, people began telling stories about him and sang songs to this clever outlaw. The many legends of Juan Chávez and corridos sung about his exploits survive to this day not only in Aguascalientes but into the broader Mexican national culture. The press at the time had two nicknames for him: “Ídolo de las Beatas” or “Rojas de los mochos.” The first nickname, “Ídolo de las Beatas,“ or “Idol of the Blessed Ones,” in English, came from his rejection of government reforms restricting the power of the Church in Mexico. The second nickname, “Rojas de los mochos” has no easy translation into 21st Century English and may loosely refer to the bloody end of a butt of a rifle. The liberal press at the time painted Juan Chávez as a conservative which he was. The legendary bandit seemed more aligned with the political beliefs of his natural father, the hacienda owner Juan Dávalos, and the landed gentry of the area which disliked ever-increasing control from the central government in Mexico City.

Banditry has existed throughout Mexican history in times and areas in which highly unequal socio-economic conditions existed combined with lax government law enforcement. Much of rural Mexico in the 19th Century was left to fend for itself and besides the clerical class there were basically two classes of people in most of the Mexican countryside: the landed gentry and the peones, the landless peasants who worked the land in a state of semi-servitude. Many clever men of low birth but with high ambition turned to banditry to become upwardly mobile and gain the wealth and status afforded to others by mere birth. The bandits became legends because many landless and powerless people in the countryside desired a better life and to break free from their circumstances but couldn’t for one reason or another. Bandits, while often violent and outside the law, became folk heroes, a resistance made up of ordinary people fighting an unjust system in all its dimensions. Local governments in Mexico tried combatting banditry, but it was an uphill battle. Juan Chávez’ own state of Aguascalientes issued a decree in October of 1859 compelling hacienda owners to do their part in helping keep the peace in the rural areas. The state required each hacienda owner to assign a contingent of men, “to protect the security of the respective farms and to constitute a useful force to carry out their defense and persecution of the bandits.” It took a year for Esteban Ávila, the governor of the state of Aguascalientes to enforce the rural militia law. The hacendados agreed reluctantly to contribute 3 or 4 men apiece to form what was called the “Reform Squadrons.” These forced volunteer squadrons proved ineffective. Governor Ávila came up with a new plan by 1862. The state of Aguascalientes would grant amnesty to all bandits who would turn themselves in, swear an oath to give up banditry, and return to private life. Governor Ávila had Juan Chávez in mind when he put forth the proposal. Surprisingly, upon hearing the offer, Juan Chávez accepted, and swore to remain, “peacefully in the domestic home.” Chávez’ adult life had never been peaceful, however, and the former bandit soon grew restless. While contemplating a return to his former ways, Juan Chávez received a proposition from the Aguascalientes governor to fill a new position. The governor offered Chávez a commission to head the Ocampo Squadron, a quasi-military force organized by the state to hunt down the remaining bandits who did not agree to Ávila’s terms of amnesty. In another surprise, Chávez accepted this, and the once-chief bandit of the state of Aguascalientes became its chief bandit hunter.

Banditry has existed throughout Mexican history in times and areas in which highly unequal socio-economic conditions existed combined with lax government law enforcement. Much of rural Mexico in the 19th Century was left to fend for itself and besides the clerical class there were basically two classes of people in most of the Mexican countryside: the landed gentry and the peones, the landless peasants who worked the land in a state of semi-servitude. Many clever men of low birth but with high ambition turned to banditry to become upwardly mobile and gain the wealth and status afforded to others by mere birth. The bandits became legends because many landless and powerless people in the countryside desired a better life and to break free from their circumstances but couldn’t for one reason or another. Bandits, while often violent and outside the law, became folk heroes, a resistance made up of ordinary people fighting an unjust system in all its dimensions. Local governments in Mexico tried combatting banditry, but it was an uphill battle. Juan Chávez’ own state of Aguascalientes issued a decree in October of 1859 compelling hacienda owners to do their part in helping keep the peace in the rural areas. The state required each hacienda owner to assign a contingent of men, “to protect the security of the respective farms and to constitute a useful force to carry out their defense and persecution of the bandits.” It took a year for Esteban Ávila, the governor of the state of Aguascalientes to enforce the rural militia law. The hacendados agreed reluctantly to contribute 3 or 4 men apiece to form what was called the “Reform Squadrons.” These forced volunteer squadrons proved ineffective. Governor Ávila came up with a new plan by 1862. The state of Aguascalientes would grant amnesty to all bandits who would turn themselves in, swear an oath to give up banditry, and return to private life. Governor Ávila had Juan Chávez in mind when he put forth the proposal. Surprisingly, upon hearing the offer, Juan Chávez accepted, and swore to remain, “peacefully in the domestic home.” Chávez’ adult life had never been peaceful, however, and the former bandit soon grew restless. While contemplating a return to his former ways, Juan Chávez received a proposition from the Aguascalientes governor to fill a new position. The governor offered Chávez a commission to head the Ocampo Squadron, a quasi-military force organized by the state to hunt down the remaining bandits who did not agree to Ávila’s terms of amnesty. In another surprise, Chávez accepted this, and the once-chief bandit of the state of Aguascalientes became its chief bandit hunter.

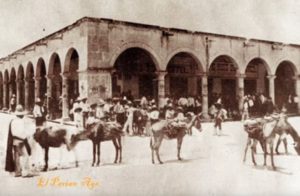

Things were going well for Juan Chávez. His Ocampo Squadron cleaned up the countryside and he was hailed as a different type of hero. This, too, would change within the year, though. Chávez’ relations with the state government deteriorated when the President of Mexico, Benito Juárez, forced Esteban Ávila to leave the government. President Juárez appointed the liberal-leaning Ponciano Arriaga to the position of governor until elections could be held later that year. On October 20, 1862, José María Chávez Alonso became the new governor. Chávez Alonso, a former editor of newspapers and magazines and one of the authors of the Aguascalientes state constitution, did not see eye to eye with the former bandit Juan Chávez. The month after the new governor took power, Juan Chávez was back to his former profession. The ex-bandit turned bandit hunter turned bandit saw a wider trajectory for the rest of his life, however. His taste of state and  national politics opened a broader world to him. This was all happening during a very volatile time in Mexican history. Earlier in 1862 – on May 5th, in fact – a French invasion force was defeated by the Mexicans in the Battle of Puebla, but the French had not given up on their designs for Mexico. The conservatives and the wealthy elites who despised the Juárez presidency wanted the French intervention in Mexico. Juan Chávez, who had always identified with the conservatives, thought of joining up with the French to help overthrow the liberal government of Aguascalientes. Without French help and together with dozens of his former bandit comrades, on November 23, 1862, Juan Chávez occupied the city of Aguascalientes, the biggest city and the capital of the state. His hold on the city didn’t last long and he retreated to the countryside. Powerful conservatives and those who backed the French intervention in Mexico had heard of Juan Chávez’ exploits in the state of Aguascalientes and sent a military advisor named Valeriano Larrúmbide to impose order and discipline on the different groups of rebels who had sympathy with the conservatives and interventionists. On February 13, 1863, the former bandit Juan Chávez along with Valeriano Larrúmbide and their small rebel army ransacked the city of Aguascalientes and left it in ruin. They did not occupy it, but Larrúmbide immediately began construction of military barracks and fortifications outside the city. Fighting continued between government-backed liberals and French-backed conservatives throughout 1863.

national politics opened a broader world to him. This was all happening during a very volatile time in Mexican history. Earlier in 1862 – on May 5th, in fact – a French invasion force was defeated by the Mexicans in the Battle of Puebla, but the French had not given up on their designs for Mexico. The conservatives and the wealthy elites who despised the Juárez presidency wanted the French intervention in Mexico. Juan Chávez, who had always identified with the conservatives, thought of joining up with the French to help overthrow the liberal government of Aguascalientes. Without French help and together with dozens of his former bandit comrades, on November 23, 1862, Juan Chávez occupied the city of Aguascalientes, the biggest city and the capital of the state. His hold on the city didn’t last long and he retreated to the countryside. Powerful conservatives and those who backed the French intervention in Mexico had heard of Juan Chávez’ exploits in the state of Aguascalientes and sent a military advisor named Valeriano Larrúmbide to impose order and discipline on the different groups of rebels who had sympathy with the conservatives and interventionists. On February 13, 1863, the former bandit Juan Chávez along with Valeriano Larrúmbide and their small rebel army ransacked the city of Aguascalientes and left it in ruin. They did not occupy it, but Larrúmbide immediately began construction of military barracks and fortifications outside the city. Fighting continued between government-backed liberals and French-backed conservatives throughout 1863.

While fighting continued sporadically throughout 1863 in the state of Aguascalientes there were massive changes underway in national politics. By June 1863 the French army had occupied Mexico City and proclaimed a military junta and then a provisional government. The Juárez government fled to El Paso, Texas to operate in exile. By October of 1863, after “The Catholic Empire of Mexico” had been proclaimed, the newly created Crown of Mexico was offered to Maximilian von Habsburg, a younger brother of the Emperor of Austria, Franz Josef the First. Napoleon the Third of France brokered this deal. With Mexico City under foreign occupation and the French army taking control of surrounding Mexican states, by the end of 1863 the legendary bandit Juan Chávez found himself in the middle of history. The French had complete control of the state of Aguascalientes by December of 1863, and the military commanders wanted to appoint a loyal local to administer their newly conquered territory. They turned to Juan Chávez. On December 21, 1863, Juan Chávez the bandit became governor of Aguascalientes. He immediately adopted the motto “Long Live Religion, Long Live the Regency of the Empire,” and proceeded to dismantle many of the supposed reforms enacted by the liberal government before him.

In February of 1864, the French army returned to Aguascalientes, thanked Juan Chávez for his service and replaced him with a man named Cayetano Basave. The former bandit did not feel slighted at the replacement. He did not prefer the life of a politician, so upon his leaving the governorship, he rejoined the interventionists led by the French, and pursued his former foes, the former liberal leaders of his home state. At the battle of Jerez, forces led by Juan Chávez captured the former Aguascalientes governor José María Chávez Alonso. The former governor was taken to the city of Zacatecas and faced a firing squad a few days later in the town of Malpaso. As a reward for his valor and dedication, in July of 1864 Emperor Maximilian called Juan Chávez to Mexico City to give his personal thanks to the former bandit. Juan Chávez knelt before the European monarch and accepted a jewel-encrusted sword for his service to the Empire. As history records, the empire would not last, and eventually forces loyal to the liberals and the Mexican Republic regained control of the country. By 1867 the French Intervention was over.

Juan Chávez again returned to his old ways and lived with the bandits in the hills of Aguascalientes, preying on travelers and occasionally looting businesses and government offices. In February of 1868, the new governor of the state, a man named Jesús Gómez Portugal offered a bounty for the head of Juan Chávez and issued a decree to seize all his assets to be sold off at auction. Juan Chávez proved as elusive as he always had been. Throughout 1868 the local Aguascalientes press speculated on his whereabouts. Some sightings put him in Jalisco, others in Zacatecas, while others said he had fled to the rugged mountains of San Luís Potosí. On February 15, 1869 the fans and foes of Juan Chávez would know of his fate. On the road to the town of Arrona, Chávez had an argument with two of the members of his bandit troop, Viviano Nieves and Agatón Chávez. On the night of February 14, 1869, the two murdered the famous bandit while he slept.

The story of the legendary bandit Juan Chávez does not end with his untimely death at the age of 37. Soon after his death, people began wondering what happened to the massive amounts of loot that Juan Chávez had acquired during his nearly two decades of being a bandit. What happened to some of his personal property, like the jeweled sword presented to him by Emperor Maximilian? Rumors swirled across Aguascalientes and the surrounding states and only grew more intense and far-fetched over time. One of the rumors persisting many years after his death which may have basis in fact, had to do with a secret tunnel system in two hilly areas the bandit frequented. The stories came out decades after Juan Chávez’ passing, mostly coming from deathbed tales from former bandit associates and surviving relatives of those who rode with him. In one account, the tunnels were large enough to ride into with a horse and they went into the hillsides for miles. While this supposed tunnel network may have been a system of yet-undiscovered caves, some have speculated that the tunnel system belonged to a lost indigenous race, or even an underground civilization of surviving ancient Maya. The tunnel system explains the ease by which Juan Chávez eluded authorities during the height of his bandit days. Many treasure hunters have tried to find these secret hiding places with no luck. Perhaps Juan Chávez gave orders to his associates to seal off the caves in the event of his untimely death. Perhaps the tunnel system is just part of the ever-growing legend of the bandit. We are still left with unanswered questions regarding the whereabout of the loot, if there was any hidden treasure to begin with. The secret wealth aside, Juan Chávez remains one of the most little-known but fascinatingly colorful figures in Mexican history.

The story of the legendary bandit Juan Chávez does not end with his untimely death at the age of 37. Soon after his death, people began wondering what happened to the massive amounts of loot that Juan Chávez had acquired during his nearly two decades of being a bandit. What happened to some of his personal property, like the jeweled sword presented to him by Emperor Maximilian? Rumors swirled across Aguascalientes and the surrounding states and only grew more intense and far-fetched over time. One of the rumors persisting many years after his death which may have basis in fact, had to do with a secret tunnel system in two hilly areas the bandit frequented. The stories came out decades after Juan Chávez’ passing, mostly coming from deathbed tales from former bandit associates and surviving relatives of those who rode with him. In one account, the tunnels were large enough to ride into with a horse and they went into the hillsides for miles. While this supposed tunnel network may have been a system of yet-undiscovered caves, some have speculated that the tunnel system belonged to a lost indigenous race, or even an underground civilization of surviving ancient Maya. The tunnel system explains the ease by which Juan Chávez eluded authorities during the height of his bandit days. Many treasure hunters have tried to find these secret hiding places with no luck. Perhaps Juan Chávez gave orders to his associates to seal off the caves in the event of his untimely death. Perhaps the tunnel system is just part of the ever-growing legend of the bandit. We are still left with unanswered questions regarding the whereabout of the loot, if there was any hidden treasure to begin with. The secret wealth aside, Juan Chávez remains one of the most little-known but fascinatingly colorful figures in Mexican history.

REFERENCES

paratodomexico web site

Wikipedia (Spanish version)