Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In March of 1860, Alexander the Third, who was styled “Emperor and Autocrat of All Russia” was anticipating a visit from a diminutive and distinct-looking Mexican woman from Sinaloa named Julia Pastrana. His Imperial Majesty along with his subjects and most of Europe at the time were curious to be in the presence of this young Mexican woman who was sure to amaze them with her appearance and delight them with her beautiful voice. The performance before the royal court in Russia was not to be, however, as this woman’s life was cut short by tragedy. Julia was no stranger to tragedy, though, as she experienced much of it in her brief but amazing life. Although most Mexicans in the 21st Century have never heard of Julia Pastrana, she was undoubtedly the most famous Mexican woman in the world in the mid-1800s. This is the story of the life and times of Julia Pastrana, Mexico’s “Ape Woman.”

In March of 1860, Alexander the Third, who was styled “Emperor and Autocrat of All Russia” was anticipating a visit from a diminutive and distinct-looking Mexican woman from Sinaloa named Julia Pastrana. His Imperial Majesty along with his subjects and most of Europe at the time were curious to be in the presence of this young Mexican woman who was sure to amaze them with her appearance and delight them with her beautiful voice. The performance before the royal court in Russia was not to be, however, as this woman’s life was cut short by tragedy. Julia was no stranger to tragedy, though, as she experienced much of it in her brief but amazing life. Although most Mexicans in the 21st Century have never heard of Julia Pastrana, she was undoubtedly the most famous Mexican woman in the world in the mid-1800s. This is the story of the life and times of Julia Pastrana, Mexico’s “Ape Woman.”

Pastrana was born in August of 1834, somewhere in the sierras of the state of Sinaloa. Some researchers believe that it was in the village of Ocaroni in the western part of the state. She was born with multiple genetic conditions. Scientists now identify one of her conditions as “generalized hypertrichosis lanuginosa” also known as “hypertrichosis terminalis.” This condition was responsible for her body being almost completely covered in straight black hair. Her jaw was irregular, and this was because of another condition called “gingival hyperplasia” which also thickened her gums and lips, making her mouth have a protruding look. In addition to these two conditions, Julia Pastrana had unusually large ears and a wide protruding nose. She also stood at only about 4 feet 5 inches.

Many versions exist of Julia’s early years, and some of these may be later embellishments made to enhance the mystique surrounding her. Many sources claim that she was indigenous, even stating that Julia was either Yaqui or Mayo. One source cited claimed that she belonged to a semi-nomadic people which roamed the mountains and deserts near the US-Mexico border. In the literature that came out later in her life, it was claimed that the tribe Julia belonged to was called the “Root Diggers.” These people were supposedly more apelike than human, and they lived in caves. According to  this version of Pastrana’s origins, a Mexican woman only known as Señora Espinosa was kidnapped by members of this Root Digger tribe and held captive in one of the tribe’s caves. When Espinosa was able to evade her captors and escaped the cave, she took the young Julia with her. Yet another story claimed that Julia’s village rejected her, calling her the “wolf girl” and thought she was possessed by evil spirits or was transformed into her present state by a sorcerer from a rival village. Whatever the true story may be, it is known that Julia lived with her mother until her mother passed away at which time she began living with her uncle. Her uncle, by all credible accounts, then sold her off to a circus. In her early teens she was rescued from the circus by the governor of Sinaloa at the time, a man named Pedro Sánchez, and would live with the governor’s family in Culiacán. While with the Sánchez family, Julia lived the life of upper-class Mexican privilege. She even had private tutors and learned how to speak French and English and also received training in singing, eventually singing opera as a mezzo-soprano. She lived at the Sánchez home until the age of 20. In the year 1854, a customs official from Mazatlán named Francisco Sepúlveda purchased Julia from the Sánchez family and took her on the road doing song and dance shows in Guadalajara, Mexico City and Veracruz. According to one account it was a few months into her new life of touring when Julia and Sepúlveda went to New Orleans and met up with Theodore Lent who would partner with them to promote Julia in the United States. It was on a trip to Baltimore when Theodore Lent and Julia eloped, and Lent took over managing Julia’s career.

this version of Pastrana’s origins, a Mexican woman only known as Señora Espinosa was kidnapped by members of this Root Digger tribe and held captive in one of the tribe’s caves. When Espinosa was able to evade her captors and escaped the cave, she took the young Julia with her. Yet another story claimed that Julia’s village rejected her, calling her the “wolf girl” and thought she was possessed by evil spirits or was transformed into her present state by a sorcerer from a rival village. Whatever the true story may be, it is known that Julia lived with her mother until her mother passed away at which time she began living with her uncle. Her uncle, by all credible accounts, then sold her off to a circus. In her early teens she was rescued from the circus by the governor of Sinaloa at the time, a man named Pedro Sánchez, and would live with the governor’s family in Culiacán. While with the Sánchez family, Julia lived the life of upper-class Mexican privilege. She even had private tutors and learned how to speak French and English and also received training in singing, eventually singing opera as a mezzo-soprano. She lived at the Sánchez home until the age of 20. In the year 1854, a customs official from Mazatlán named Francisco Sepúlveda purchased Julia from the Sánchez family and took her on the road doing song and dance shows in Guadalajara, Mexico City and Veracruz. According to one account it was a few months into her new life of touring when Julia and Sepúlveda went to New Orleans and met up with Theodore Lent who would partner with them to promote Julia in the United States. It was on a trip to Baltimore when Theodore Lent and Julia eloped, and Lent took over managing Julia’s career.

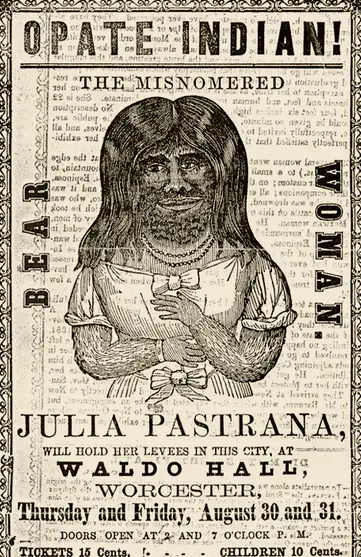

It was while touring the US appearing at freak shows, side shows and dance venues when Julia became famous, and her popularity began to soar. While on the road she had many names: “The Bear Woman,” “The Baboon Lady,” “The Hairy Woman,” “The Ape Woman,” “The Animal-Human Hybrid,” “The Nondescript” and “The Ugliest Woman in the World.” As some circus venues had their token “Bearded Lady,” Julia Pastrana was rarely advertised as such, because her looks went beyond the norm of ordinary freak show fare.

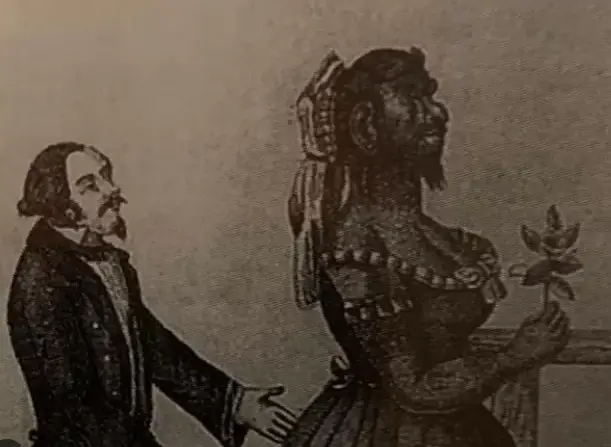

Her peculiar set of conditions attracted the attention of medical professionals and scientists. Julia’s manager and husband, Theodore Lent, encouraged curious doctors and academics to examine her, so that expert opinions and statements made to the press would enhance Julia’s aura of mystery and lead to an increase in her popularity. Famous New York surgeon Alexander B. Mott publicly declared that Julia was a cross between a human and an orangutan. The fact that orangutans are native to the jungles of southeast Asia and have no connection to Mexico didn’t seem to factor into this bizarre diagnosis. Others declared she was a “distinct species” of human, while different medical examiners stated that Julia was simply a “deformed Indian woman.” The most famous natural scientist of the 19th Century, Charles Darwin of “Theory of Evolution” fame, even chimed in, but after Julia’s death. Some sources claim that Darwin examined her while alive, but in truth he never met her in person, nor did he ever see her body after death. Dawin stated:

“Julia Pastrana, a Spanish dancer, was a remarkably fine woman, but she had a thick masculine beard and a hairy forehead; she was photographed, and her stuffed skin was exhibited as a show; but what concerns us is, that she had in both the upper and lower jaw an irregular double set of teeth, one row being placed within the other, of which Doctor Purland took a cast. From the redundancy of the teeth her mouth projected, and her face had a gorilla-like appearance.”

“Julia Pastrana, a Spanish dancer, was a remarkably fine woman, but she had a thick masculine beard and a hairy forehead; she was photographed, and her stuffed skin was exhibited as a show; but what concerns us is, that she had in both the upper and lower jaw an irregular double set of teeth, one row being placed within the other, of which Doctor Purland took a cast. From the redundancy of the teeth her mouth projected, and her face had a gorilla-like appearance.”

It’s doubtful that Darwin even saw this alleged cast of teeth. Pastrana’s condition of gingival hyperplasia, or overgrown gums, caused her mouth to jut out, giving her lower face the appearance of a primate. The multiple rows of teeth condition seems to have been just a rumor, perhaps perpetuated while Pastrana was still alive, once again, to add to her mystique in hopes of increasing her popularity.

In the late 1850s, Lent and Pastrana did a grand tour of Europe, playing to sold-out venues. In 1857 at Regent’s Gallery in London, she performed three times a day, always singing in Spanish and doing traditional Mexican dances. The couple would cross the continent and tour Germany and various cities in the Austro-Hungarian Empire before heading on to Moscow. It was in Vienna where Julia made friends with some important performers and showmen. Among them was Austrian circus owner Hermann Otto. In his book, Fahrend Volk, or “Traveling People” he has this to say about Julia Pastrana:

“She was a monster to the whole world, an abnormality put on display for money, someone who had been taught a few artistic turns, like a trained animal. [But] for the few who knew her better, she was a warm, feeling, thoughtful, spiritually very gifted being with a sensitive heart and mind. . . and it affected her very deeply in her heart with sadness, having to stand beside people, instead of with them, and to be shown as a freak for money, not sharing any of the everyday joys in a home filled with love.”

In the winter of 1859, Lent and Pastrana left Vienna and traveled to Moscow where Julia would be performing at the Circus Salomansky. It was On March 20, 1860, when Julia gave birth to her first child. The baby boy, who was unusually large, was born with the same conditions as she had. The baby died almost immediately, and Julia remained hospitalized after the birth. She would die a few days later and her official cause of death was determined to be peritonitis which was a complication brought on by a difficult childbirth. While Julia spent those last few days of her life in the Russian hospital, her husband, Theodore Lent, sold tickets to view her in her hospital bed. There was a line out the door.

After Julia Pastrana’s death, Theodore Lent sold her body and their son’s body to Moscow University professor named Sukolov who invented an embalming technique that combined mummification with taxidermy. After seeing how well-preserved the bodies were, and what a popular attraction Julia still was after death, Lent bought the bodies back from the professor and began exhibiting them throughout Europe at various circuses and freak shows. In 1862, Julia and the boy were on display for quite some time in London and the cost to see them was one shilling.

While Theodore Lent was in Karlsbad, a city in the modern-day Czech Republic, he met a woman named Marie Bartel with similar conditions to Julia’s. He married her and started passing her off as Julia’s younger sister, even billing her as “Zenora Pastrana.” The two eventually retired to Saint Petersburg, Russia. Soon after they moved there, Lent began exhibiting bizarre behaviors. Marie Bartel eventually had him committed and Lent later died in a Russian insane asylum. Marie returned to Karlsbad, with the taxidermy bodies of Julia and her son, and rented them out to fairs, side shows and chambers of horror throughout Germany and Austria-Hungary. It’s unknown when Marie Bartel, aka “Zenora Pastrana” died but by the early 1920s, the bodies were owned by an American who was living in Berlin. In 1921, the American sold them to a man named Haakon Lund who owned the largest freak show in Norway. Lund had a total of over 8,000 objects in what he called his Hygienic and Anatomical Exhibition, including Siamese twin embryos, various preserved heads and an extensive macabre wax museum. Throughout the 1920s the show toured throughout Norway. Lund’s slogan for his exhibition was, “Humanity, know thyself.”

The bodies survived World War II and Lund eventually put the Pastranas in storage as the post-war world looked less kindly on freak shows and bizarre exhibits of human deformities. In the 1970s some teenagers broke into this storage facility and vandalized the bodies. One of Julia’s arms was torn off and the body of the infant was so damaged that it ended up in the trash. In the 1990s Julia’s body found a more permanent place in the Institute of Basic Medical Science at the University of Oslo.

The bodies survived World War II and Lund eventually put the Pastranas in storage as the post-war world looked less kindly on freak shows and bizarre exhibits of human deformities. In the 1970s some teenagers broke into this storage facility and vandalized the bodies. One of Julia’s arms was torn off and the body of the infant was so damaged that it ended up in the trash. In the 1990s Julia’s body found a more permanent place in the Institute of Basic Medical Science at the University of Oslo.

In the year 2005, a Mexican artist named Laura Anderson Barbata who was doing a residency in Norway was moved by Julia Pastrana’s story. Anderson began petitioning various Norwegian government ministries to repatriate Julia’s body back to Mexico where she could have a formal burial in her native land. With the help of Mexico’s ambassador to Norway and the governor of Julia’s home state of Sinaloa, Anderson was successful in completing her quest. In February of 2013, in a white coffin covered in white roses, Julia Pastrana was laid to rest in the town of Sinaloa de Leyva, near where she was born. Although troubling and disturbing, the Julia Pastrana story had a happier ending than anything Julia could have imagined or expected while she was alive. May she rest in peace.

REFERENCES

Gylseth, Christopher Hals and Lars O. Tovrud. Julia Pastrana: The Tragic History of the Victorian Ape Woman. Cheltenham, UK: The History Press, 2001. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/49G8BQy