Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was June 20th 2020 and the place was downtown Los Angeles, California. A few dozen people gathered at Father Serra Park, just south of Olvera Street, in the heart of old Mexican Los Angeles. Alan Salazar, an elder of both the Taviam and Chumash tribes of southern California, burned sage and invoked the spirits of his ancestors before he grabbed the megaphone. Near the end of Salazar’s speech, the crowd began to chant, “Tear it down! Tear it down!” and turned their focus to the bronze statue of Junipero Serra, the 18th Century Franciscan friar who is credited with starting the California mission system in the late 1760s. The members of the crowd grabbed sturdy ropes, wrapped them around the statue and began pulling. The bronze sculpture began to rock back and forth before it came crashing to the ground. Father Serra’s cross – held up above his head in his right hand – broke off as the statue hit the cement. Two members of the protesting group splashed red paint on the toppled statue. As the Franciscan lay there, two little girls climbed on his back and posed for photos. Their parents would post the images on social media later that day. The day before, a similar event took place up the coast in San Francisco. A group of nearly 100 people gathered at Golden Gate Park near the De Young Museum and the California Academy of Sciences at a place known as the Music Concourse. There, protestors tore down statues of President Ulysses S. Grant, “The Star Spangled Banner” author Francis Scott Key and Father Junipero Serra. Statues of Spanish author Miguel Cervantes’ characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza were also vandalized, but not taken down. In comments to news media later that day, San Francisco mayor London Breed would not take sides in the statue debate and would not seek to prosecute any of the people involved in the protests. She did say, “I have asked the Arts Commission, the Human Rights Commission, and the Recreation and Parks Department to work with the community to evaluate our public art and its intersection with our country’s racist history.” It’s not likely that the statues of Father Serra will ever return to Golden Gate Park or to the park named for him in downtown LA.

The date was June 20th 2020 and the place was downtown Los Angeles, California. A few dozen people gathered at Father Serra Park, just south of Olvera Street, in the heart of old Mexican Los Angeles. Alan Salazar, an elder of both the Taviam and Chumash tribes of southern California, burned sage and invoked the spirits of his ancestors before he grabbed the megaphone. Near the end of Salazar’s speech, the crowd began to chant, “Tear it down! Tear it down!” and turned their focus to the bronze statue of Junipero Serra, the 18th Century Franciscan friar who is credited with starting the California mission system in the late 1760s. The members of the crowd grabbed sturdy ropes, wrapped them around the statue and began pulling. The bronze sculpture began to rock back and forth before it came crashing to the ground. Father Serra’s cross – held up above his head in his right hand – broke off as the statue hit the cement. Two members of the protesting group splashed red paint on the toppled statue. As the Franciscan lay there, two little girls climbed on his back and posed for photos. Their parents would post the images on social media later that day. The day before, a similar event took place up the coast in San Francisco. A group of nearly 100 people gathered at Golden Gate Park near the De Young Museum and the California Academy of Sciences at a place known as the Music Concourse. There, protestors tore down statues of President Ulysses S. Grant, “The Star Spangled Banner” author Francis Scott Key and Father Junipero Serra. Statues of Spanish author Miguel Cervantes’ characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza were also vandalized, but not taken down. In comments to news media later that day, San Francisco mayor London Breed would not take sides in the statue debate and would not seek to prosecute any of the people involved in the protests. She did say, “I have asked the Arts Commission, the Human Rights Commission, and the Recreation and Parks Department to work with the community to evaluate our public art and its intersection with our country’s racist history.” It’s not likely that the statues of Father Serra will ever return to Golden Gate Park or to the park named for him in downtown LA.

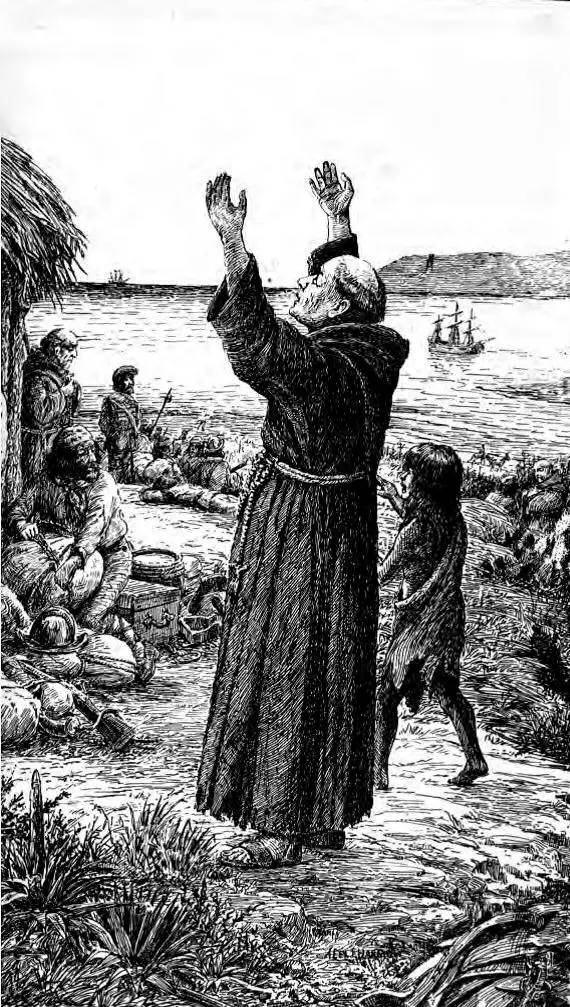

Who was Junipero Serra? He was born Miquel Josep Serra y Ferrer to a humble farming family on the island of Mallorca in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Spain on November 24, 1713. At age 16 he enrolled in a Franciscan school in the island’s capital, Palma de Mallorca, where he studied philosophy. A few days before his 17th birthday, the young aspiring priest joined the Franciscan Order at Palma. This branch of the order was called the Alcanterine Branch, also known as the “Observant Franciscans,” who strictly observed St. Francis’ teachings. The teenage boy adopted the name Junipero after an early follower and companion of St. Francis of Assissi known in Catholic history as Brother Juniper. In the 7 years it took for Serra to become a priest, he immersed himself in the usual tasks of monasterial life and also studied philosophy, metaphysics, theology and cosmology. In the years immediately after Serra became ordained as a priest, he taught philosophy at the Convento de San Francisco and later worked on a doctorate on theology. By 1748, Serra had decided that he wanted to pursue the life of a missionary overseas and in 1749 he was on a ship with a group of other Franciscans bound for the New World.

Who was Junipero Serra? He was born Miquel Josep Serra y Ferrer to a humble farming family on the island of Mallorca in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Spain on November 24, 1713. At age 16 he enrolled in a Franciscan school in the island’s capital, Palma de Mallorca, where he studied philosophy. A few days before his 17th birthday, the young aspiring priest joined the Franciscan Order at Palma. This branch of the order was called the Alcanterine Branch, also known as the “Observant Franciscans,” who strictly observed St. Francis’ teachings. The teenage boy adopted the name Junipero after an early follower and companion of St. Francis of Assissi known in Catholic history as Brother Juniper. In the 7 years it took for Serra to become a priest, he immersed himself in the usual tasks of monasterial life and also studied philosophy, metaphysics, theology and cosmology. In the years immediately after Serra became ordained as a priest, he taught philosophy at the Convento de San Francisco and later worked on a doctorate on theology. By 1748, Serra had decided that he wanted to pursue the life of a missionary overseas and in 1749 he was on a ship with a group of other Franciscans bound for the New World.

Serra landed at the Mexican port of Veracruz in late 1749. True to his vows, instead of using a horse, he walked to Mexico City on the Camino Real which stretched from Veracruz to the capital city through jungles and deserts and over mountains and high plains. He traveled with no money or supplies and depended on the kindnesses of those he encountered along the way. Before he left the tropical lowlands, he was bitten by a mosquito on his foot and that bite became infected, something that would remain with him for the rest of his life. Serra hobbled into Mexico City and took up residence at the Colegio de San Fernando de México, a training center for Franciscan missionaries. Serra was assigned to the missions to the Pame Indians located 90 miles north of the city of  Querétaro in the town of Jalpan, nestled in the rugged Sierra Gorda mountains. Serra found the missions in disarray, and along with other newly arrived missionaries he started to spruce up and develop the missions and surrounding lands. To Serra, his predecessors had been lax in converting the local indigenous people, so he endeavored to learn their language and preach the Gospel in Pame. Serra also oversaw the construction of a beautiful church which still stands in the town of Jalpan. He not only used local indigenous laborers and craftsmen to build the church, he had some of the finest carpenters and artists from Mexico to come to the remote outpost to work on this ornate place of worship. In 1752, on a return trip to Mexico City, Father Serra asked that a representative of the Holy Inquisition be appointed to the Sierra Gorda to help combat a rise in witchcraft and other non-churchly practices in the area. In a surprise move, Inquisition officials appointed Serra himself to the position of Inquisitor, and gave him the power to enforce the Holy Inquisition in all lands he served in or traveled to that did not already have a representative from the Inquisition working there. Serra returned to the north and filed reports – two of which survive to this day – of people whom he condemned for practicing sorcery. As indigenous people were exempt from the Inquisition unless they were already Christianized, the records show that Serra filed reports on two people of Afro-Mexican descent, a group which has been shown as overrepresented in the records of the Holy Inquisition in Mexico City. For a brief history of Afro-Mexicans, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 99. https://mexicounexplained.com//afro-mexicans-hidden-heritage/

Querétaro in the town of Jalpan, nestled in the rugged Sierra Gorda mountains. Serra found the missions in disarray, and along with other newly arrived missionaries he started to spruce up and develop the missions and surrounding lands. To Serra, his predecessors had been lax in converting the local indigenous people, so he endeavored to learn their language and preach the Gospel in Pame. Serra also oversaw the construction of a beautiful church which still stands in the town of Jalpan. He not only used local indigenous laborers and craftsmen to build the church, he had some of the finest carpenters and artists from Mexico to come to the remote outpost to work on this ornate place of worship. In 1752, on a return trip to Mexico City, Father Serra asked that a representative of the Holy Inquisition be appointed to the Sierra Gorda to help combat a rise in witchcraft and other non-churchly practices in the area. In a surprise move, Inquisition officials appointed Serra himself to the position of Inquisitor, and gave him the power to enforce the Holy Inquisition in all lands he served in or traveled to that did not already have a representative from the Inquisition working there. Serra returned to the north and filed reports – two of which survive to this day – of people whom he condemned for practicing sorcery. As indigenous people were exempt from the Inquisition unless they were already Christianized, the records show that Serra filed reports on two people of Afro-Mexican descent, a group which has been shown as overrepresented in the records of the Holy Inquisition in Mexico City. For a brief history of Afro-Mexicans, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 99. https://mexicounexplained.com//afro-mexicans-hidden-heritage/

In 1767 Serra’s life changed once again when the King of Spain, Charles the Third, issued a proclamation expelling the Jesuit Order from all Spanish territories. The Viceroy of New Spain, the French-born Carlos Francisco de Croix, carried out the king’s decree swiftly, but it took a while to expel all the members of the Order from the viceroy’s jurisdiction. For the previous 70 years the Jesuits had pretty much total control over the remote peninsula of Baja California. For more information about the Jesuit history in Baja, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 33 titled “The Lost Mission of Santa Isabel.” https://mexicounexplained.com//lost-mission-santa-isabel/ The Jesuit expulsion left a huge vacuum in the missions and towns of that region. Back at the Franciscan headquarters at the Colegio de San Fernando in Mexico City, the Franciscan friars drew up plans to fill that void left by the forced evacuation of the Jesuits. They quickly named Father Junipero Serra as President of the Missions of the Californias. Serra was soon on a ship from the Pacific port of San Blas to sail up the coast to the mission at Loreto on the eastern side of the Baja Peninsula. He was welcomed warmly by the governor of the province known as Las Californias, a man named Gaspar de Portolá, who had recently been appointed to his post. Again, Serra arrived at a place that was severely mismanaged. Since the expulsion of the Jesuits, the Spanish military had been in charge of all 13 Baja California missions. In 1768, New Spain’s Inspector General, José de Gálvez, who was appalled at the misadministration of the missions by the military, gave full control over the missions to the Franciscans. Inspector General Gálvez had grander plans for this remote corner of the Spanish Empire, and Serra would play an important role in these plans.

By the 1760s Spain grew concerned over the fragile hold they had over their claims to the western parts of North America. Russians from Alaska had established forts and trading outposts as far south as the northern part of the modern-day US state of California. The English, too, had stepped up their activity in the region. While Spain technically claimed those lands north of the peninsula of Baja California, they never settled any of it. From his offices in Mexico City, Inspector General Gálvez formulated plans to extend the mission system found in Baja up the coast, all the way to Monterey Bay. At the time, the territory of the present-day American state of California was known as Alta California, to distinguish it from the peninsula known as Baja California. The Spanish sent two ships up the California coast to scout for mission locations, and then a formal expedition of settlement and colonization began in 1769. Serra traveled overland from Loreto with his destination at San Diego Bay, where the city of San Diego, California is now located. It took him 52 days to make the overland trek and he almost died as the infection from his foot, from that mosquito bite in the jungles outside Veracruz, spread up his leg. Serra asked one of the indigenous young men who accompanied him on the trip if he could help with the infection. The young man gathered local plants, ground them up, mixed them with sheep fat and rubbed the ointment into the infection. While some call Serra’s recovery a miracle, others credit local indigenous plant knowledge with this rapid healing. Nonetheless, the 52-year-old friar reached his destination on July 1, 1769 and set to work on building a mission.

By the 1760s Spain grew concerned over the fragile hold they had over their claims to the western parts of North America. Russians from Alaska had established forts and trading outposts as far south as the northern part of the modern-day US state of California. The English, too, had stepped up their activity in the region. While Spain technically claimed those lands north of the peninsula of Baja California, they never settled any of it. From his offices in Mexico City, Inspector General Gálvez formulated plans to extend the mission system found in Baja up the coast, all the way to Monterey Bay. At the time, the territory of the present-day American state of California was known as Alta California, to distinguish it from the peninsula known as Baja California. The Spanish sent two ships up the California coast to scout for mission locations, and then a formal expedition of settlement and colonization began in 1769. Serra traveled overland from Loreto with his destination at San Diego Bay, where the city of San Diego, California is now located. It took him 52 days to make the overland trek and he almost died as the infection from his foot, from that mosquito bite in the jungles outside Veracruz, spread up his leg. Serra asked one of the indigenous young men who accompanied him on the trip if he could help with the infection. The young man gathered local plants, ground them up, mixed them with sheep fat and rubbed the ointment into the infection. While some call Serra’s recovery a miracle, others credit local indigenous plant knowledge with this rapid healing. Nonetheless, the 52-year-old friar reached his destination on July 1, 1769 and set to work on building a mission.

Serra’s job proved difficult as the indigenous Kumeyaay people wanted nothing to do with the San Diego mission. In the first six months of operatioin, with not a single native baptized, the two ships attached to the expedition plied up and down the California coast looking for other sites that would be perfect to establish more missions according to the directives of the inspector general. On April 16, 1770 Serra boarded one of those ships to head north to Monterey Bay to establish the mission there. It took 6 weeks on rough seas to get from San Diego to Monterey. The mission they would establish there would be called Mission San Carlos Borromeo, located in modern-day Carmel, California. Serra would be responsible for founding many of the 21 missions in the area and would later be called The Apostle of California.

21st Century people and history itself do not know what to make of the Spanish mission system. Contrary to popular belief, the Franciscan friars in California under Serra’s leadership never rounded up nor enslaved any of the indigenous people they encountered. Critics would argue that many of the natives were forced into the mission system – which they could never leave – through pressures put on their environments due to the Spanish presence. A small famine, for example, might drive natives to seek shelter in the mission system, but once in, they could not leave. On the other hand, the missions gave all who would accept the mission lifestyle food, security, and the opportunity to learn skills like new farming techniques or a trade, like carpentry. Those examining the system may also point to the cruelty involved that seemed to be built into it by course. In Serra’s defense, the Franciscan priest spoke out against abuses by members of the Spanish military who accompanied the missionaries. In many examples, the priests separated the missions from the military presidios, often relocating them away from the military presence to prevent abuses. The cruelty visited upon the Indians, some note, was the same visited on the Europeans at their own hands. The strict branch of the Franciscan order to which Serra belonged was known for its self-abuse to enact penance, including flagellation, the wearing of thorny garments, sleep deprivation, and so on. This is not to excuse any abuses brought upon the native populations of the Californias, only to put it all into context. This context and the overall history of the mission system in colonial New Spain is constantly being reexamined and reinterpreted.

In September of 2015, Father Junipero Serra became the first person to be declared a saint on American soil when Pope Francis made his first visit to the United States. In his speech about the new saint, the pope even suggested that Serra be considered as one of the Founding Fathers of the US for all his work done in California. The canonization of Junipero Serra was not, of course, without its share of controversy. While some members of California Indian tribes attended the canonization ceremonies and praised Serra’s works among their people’s ancestors, others did not hold such positive sentiments. in October of 2015, a week after Serra was declared a saint, his statue in Monterey was decapitated. This was the beginning of years of protests and statue destructions that continue to this day. In Mexico, Father Serra is more universally revered than in the United States. He is seen as a holy man who earned the right to be called “saint.” As times change and history continues to be reexamined, the final chapter may never be written in the legacy of Father Junipero Serra.

In September of 2015, Father Junipero Serra became the first person to be declared a saint on American soil when Pope Francis made his first visit to the United States. In his speech about the new saint, the pope even suggested that Serra be considered as one of the Founding Fathers of the US for all his work done in California. The canonization of Junipero Serra was not, of course, without its share of controversy. While some members of California Indian tribes attended the canonization ceremonies and praised Serra’s works among their people’s ancestors, others did not hold such positive sentiments. in October of 2015, a week after Serra was declared a saint, his statue in Monterey was decapitated. This was the beginning of years of protests and statue destructions that continue to this day. In Mexico, Father Serra is more universally revered than in the United States. He is seen as a holy man who earned the right to be called “saint.” As times change and history continues to be reexamined, the final chapter may never be written in the legacy of Father Junipero Serra.

REFERENCES

Miranda, Carolina. “At Los Angels Toppling of Junipero Serra Statue, Activists Want Full Story Told.” Los Angeles Times, 20 Jun 2020.

Richards, Irmagarde. California Yesterdays. Sacramento: Harr Wagner Publishing Company, 1957.