Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

As an adult, Bruno Alabau relates a story from the spring of 1982:

As an adult, Bruno Alabau relates a story from the spring of 1982:

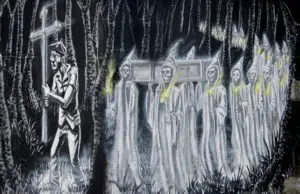

“I was a boy scout and was camping with my friends for the weekend. After dinner, at night, me and my friends played a game of hide-and-seek. I decided to skirt round the campsite through the forest and go downhill toward the trail, when I noticed some lights. I thought it might be one of my companions, so I hid behind one of the trees to give them a fright, but I turned out to be the frightened one: don’t ask me what it was, but I saw seven people in two rows of three led by another figure. All of them were dressed the same, wearing tunics that ended in hoods, like the ones worn during Holy Week. The first figure carried a large cross that seemed to be made of two flat boards, while the leaders of each row carried large tapers; the others were empty-handed. I just stood there, paralyzed, until they passed right in front of me and became lost among the trees. I ran back to the camp but didn’t dare tell anyone about what had happened, since they’d only say I was crazy.”

Sofia Pérez tells of seeing something similar:

“I was eight years old when this happened. My mother and I had gone out to visit a friend and we were walking down a trail behind my house, near the graveyard. It wasn’t very late in the day, but since it was winter, it became dark very early. Just as we reached the crossroads, I heard a strong sound of footsteps, as though many people were approaching. I asked my mother if she could hear it, and she said yes. My mother and I were paralyzed. I was very young and didn’t quite understand what I was seeing, but my mother was terrified. She held me close and told me not to make a sound… at the end of the long procession we saw a woman: ‘Tía Preciosa,’ one of our neighbors! She lived a few houses up from ours, and I recognized her way of walking, since she limped. We saw her clearly, though. She carried something like a stick in her hand and a kind of stone that looked like marble, but was very, very bright. She walked past us like a ghost, and went off with the strange procession.”

Both Bruno and Sofía were witnesses to the Santa Compaña, or the Procession of the Damned.

Both Bruno and Sofía were witnesses to the Santa Compaña, or the Procession of the Damned.

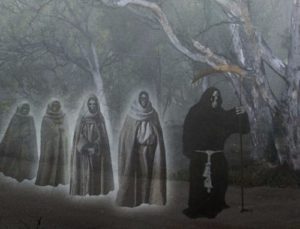

Modern-day sightings of the Santa Compaña, or “Holy Company” are now rare but were more common in the late colonial period through the 19th Century. Also known as La Güestia, La Estadea, La Estatinga or La Pantaruxada, among other names, the legend tells of a procession of figures hooded in white, sometimes two rows, sometimes in single file, with a leader carrying a cross and/or a cauldron of holy water. The march always begins at the stroke of midnight and ends at the break of dawn. The hooded figures are said to be tormented souls or souls momentarily released from eternal damnation to walk the earth to participate in this ritual. They carry candles and are sometimes accompanied by glowing orbs of light, often mistaken for UFOs. The smell of candle wax often precedes the sighting of the Santa Compaña. The procession moves quietly and is sometimes surrounded by a slightly luminescent fog. The leader of the procession, according to legend, may take on several different forms and serve different functions. Sometimes the leader is just one of the tormented souls enlisted to participate in the procession. In other versions of the legend, the leader of the Santa Compaña is a small child wearing the same clothing as the spirits he leads. If a witness looks into the hollow eyes of the child, it means death within 24 hours. The more common legend has a member of the living leading the procession. This living person is in a trance and compelled by supernatural forces to lead the Santa Compaña, unaware that he or she is a participant in this macabre event. When the procession ends at dawn, the human leader returns home to sleep and wakes up feeling extremely tired and spiritually drained and cannot remember what happened the night before. The human participant is officially under a curse and is condemned to lead the procession each day at midnight until the curse is broken. If the curse is not broken he or she will turn pale and wither away and die in a matter of weeks. The only way for the living leader of the procession to lift the curse is to pass off the cross and cauldron to an unsuspecting passerby while part of the ghostly march. The person who receives the cross and cauldron is now the victim of the curse and will also face death if he or she doesn’t pass on the Santa Compaña regalia to another unsuspecting victim.

Witnessing the passing of the Santa Compaña is never a good thing. The procession always indicates that something bad will happen, usually within 24 hours of seeing it. Most legends say that the Santa Compaña’s march ends up in a village or town or in front of a specific house where a death is about to occur. A witness to this strange group may experience anything from minor mishaps and just plain bad luck to a brutal and agonizing death. There are remedies for the person experiencing the passing of the Santa Compaña. The victim must immediately draw a chalk version of a Solomon’s Circle on the ground and lie face down in the middle of it. This drawing consists of a six-pointed star inside a circle. In some versions of the legend a black cat can be used to help prevent the curse of witnessing the Santa Compaña. The black cat is tied to a stake and put in the path of the procession. After leaving the cat if the witness runs away fast enough, there will be no curse. In some versions of the story, certain hand gestures also offer protection from all ills of being a witness. The hand gestures include making devil’s horns by extending the index and pinkie fingers and contracting the others, or by making your hand into a fist and putting your thumb in between your index and middle fingers. Some witnesses who are extremely sensitive can see the entire Santa Compaña in great detail, while some can only see the lights of the candles or the small orbs of light surrounding the procession. Others may just feel a slight breeze and smell the wax of the candles and experience feelings of fright or goosebumps.

Witnessing the passing of the Santa Compaña is never a good thing. The procession always indicates that something bad will happen, usually within 24 hours of seeing it. Most legends say that the Santa Compaña’s march ends up in a village or town or in front of a specific house where a death is about to occur. A witness to this strange group may experience anything from minor mishaps and just plain bad luck to a brutal and agonizing death. There are remedies for the person experiencing the passing of the Santa Compaña. The victim must immediately draw a chalk version of a Solomon’s Circle on the ground and lie face down in the middle of it. This drawing consists of a six-pointed star inside a circle. In some versions of the legend a black cat can be used to help prevent the curse of witnessing the Santa Compaña. The black cat is tied to a stake and put in the path of the procession. After leaving the cat if the witness runs away fast enough, there will be no curse. In some versions of the story, certain hand gestures also offer protection from all ills of being a witness. The hand gestures include making devil’s horns by extending the index and pinkie fingers and contracting the others, or by making your hand into a fist and putting your thumb in between your index and middle fingers. Some witnesses who are extremely sensitive can see the entire Santa Compaña in great detail, while some can only see the lights of the candles or the small orbs of light surrounding the procession. Others may just feel a slight breeze and smell the wax of the candles and experience feelings of fright or goosebumps.

Where did the legend of La Santa Compaña come from? Waves of immigrants from northern Spain brought the legend to the New World in the 17th Century. Mexico received three major influxes of people from Spain’s northern regions of Galicia, Asturias and the Basque Country. The first wave came in the late 1600s, a full century and a half after the Spanish Conquest. The next wave occurred in the newly independent Mexico of the 1830s, as economic conditions in the northern part of Spain compelled people to leave. The third influx happened in the 1880s when Mexico offered incentives to foreigners to settle sparsely inhabited parts of the country. With the settlers from northern Spain also came the legend and then came the reported sightings from people. Although coming to Mexico from northern Spain, the procession of the damned has its roots in the folklore of Europe’s Middle Ages. As mentioned earlier, one of the alternate names of the Santa Compaña is La Estatinga. This word may be derived from the Old English word Herlathingi, or “The Company of the Dead,” related to the mythical ancient British ruler King Herla. The Herlathingi was first described by the 13th Century Welsh-born archdeacon of Oxford named Walter Map who wrote about it in his book titled De nugis curialium. According to Map, King Herla and his entourage journeyed to a kingdom ruled by a red-haired dwarf with goat’s hooves to attend the dwarf king’s wedding. From what Map describes, the ancient British king slipped into what seems like another dimension to attend the wedding. The wedding over, King Herla returned to the human world and upon entering it his horsemen slowly turned into dust and then into ghosts. The king also succumbed to this fate. Thus, Herla and his men were condemned to walk the earth as eternal wanderers marching in ghostly form. For centuries people have claimed to see King Herla’s white-robed spectral procession. The Herlathingi is related to an older European folklore motif called “The Wild Hunt” found mostly in the Germanic and Scandinavian countries. The motif usually involves supernatural or ghostly hunters passing by in pursuit of game. The hunters can be either fairies, elves or the dead. The procession, much like the more modern-day Santa Compaña, has a leader. In the Germanic legend the leader is usually the god Woden. In other versions, the leader is a headless horseman. In rare cases, the spirits in the procession are carrying coffins. The Wild Hunt is usually preceded by the sounds of barking dogs, beating drums or blasts from trumpets. Just as in the Santa Compaña legend, living people may be pulled away out of their sleep to be part of the procession, and just like the Spanish/Mexican version of the story, seeing this strange group of marchers does not bode well for the witness. The witness can fall victim of bad luck or horrible death. Sometimes viewers of the procession were also abducted by members of the fairy realm and taken to the underworld. Similar myths of ghostly processions were found throughout ancient western Europe and reached as far east as modern-day Slovenia.

Where did the legend of La Santa Compaña come from? Waves of immigrants from northern Spain brought the legend to the New World in the 17th Century. Mexico received three major influxes of people from Spain’s northern regions of Galicia, Asturias and the Basque Country. The first wave came in the late 1600s, a full century and a half after the Spanish Conquest. The next wave occurred in the newly independent Mexico of the 1830s, as economic conditions in the northern part of Spain compelled people to leave. The third influx happened in the 1880s when Mexico offered incentives to foreigners to settle sparsely inhabited parts of the country. With the settlers from northern Spain also came the legend and then came the reported sightings from people. Although coming to Mexico from northern Spain, the procession of the damned has its roots in the folklore of Europe’s Middle Ages. As mentioned earlier, one of the alternate names of the Santa Compaña is La Estatinga. This word may be derived from the Old English word Herlathingi, or “The Company of the Dead,” related to the mythical ancient British ruler King Herla. The Herlathingi was first described by the 13th Century Welsh-born archdeacon of Oxford named Walter Map who wrote about it in his book titled De nugis curialium. According to Map, King Herla and his entourage journeyed to a kingdom ruled by a red-haired dwarf with goat’s hooves to attend the dwarf king’s wedding. From what Map describes, the ancient British king slipped into what seems like another dimension to attend the wedding. The wedding over, King Herla returned to the human world and upon entering it his horsemen slowly turned into dust and then into ghosts. The king also succumbed to this fate. Thus, Herla and his men were condemned to walk the earth as eternal wanderers marching in ghostly form. For centuries people have claimed to see King Herla’s white-robed spectral procession. The Herlathingi is related to an older European folklore motif called “The Wild Hunt” found mostly in the Germanic and Scandinavian countries. The motif usually involves supernatural or ghostly hunters passing by in pursuit of game. The hunters can be either fairies, elves or the dead. The procession, much like the more modern-day Santa Compaña, has a leader. In the Germanic legend the leader is usually the god Woden. In other versions, the leader is a headless horseman. In rare cases, the spirits in the procession are carrying coffins. The Wild Hunt is usually preceded by the sounds of barking dogs, beating drums or blasts from trumpets. Just as in the Santa Compaña legend, living people may be pulled away out of their sleep to be part of the procession, and just like the Spanish/Mexican version of the story, seeing this strange group of marchers does not bode well for the witness. The witness can fall victim of bad luck or horrible death. Sometimes viewers of the procession were also abducted by members of the fairy realm and taken to the underworld. Similar myths of ghostly processions were found throughout ancient western Europe and reached as far east as modern-day Slovenia.

As with most things paranormal and unexplained the serious researcher and the mildly curious are left asking the question, “Could the Santa Compaña have some basis in reality?” Many witnesses to the phenomenon have had no prior exposure to the legend, so what are they seeing? Cult activity? Imaginary religious processions? Pranks? Seldom investigated, for now the Santa Compaña will remain an enigma cloaked in mystery.

REFERENCES USED

Corrales, Scott and Manuel Carballal. “Night Wanderers: The Armies of Darkness.” Inexplicata website.

Matute, Alvaro. “A Century of Spanish Emigration to Mexico,” in The Splendor of Mexico, published by UNAM (no date available)

Pineda, Fran. “La Santa Compaña: The Most Widespread Galician Legend.” Vivecamino website.