Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The night of November 20, 1751 would be forever remembered as a dark day for the Spanish Empire in the New World. On that night a man named Luis Oacpicagigua, also known to history as Luis de Sáric, led a coordinated assault on the Spanish missions of Pimería Alta that took months of planning. The attack involved hundreds of warriors from a variety of desert tribes that inhabited the remotest northern territories of Spain’s North American possessions. The attack took the Spanish by surprise. Outnumbered and overwhelmed, the remaining Spanish missionaries and settlers retreated hundreds of miles to the south, fleeing a burned out and utterly demolished disaster zone. The natives who rebelled celebrated, while those not participating in the uprising bided their time and knew that Spain would be back. Luis de Sáric and his men would only enjoy a temporary victory here.

The night of November 20, 1751 would be forever remembered as a dark day for the Spanish Empire in the New World. On that night a man named Luis Oacpicagigua, also known to history as Luis de Sáric, led a coordinated assault on the Spanish missions of Pimería Alta that took months of planning. The attack involved hundreds of warriors from a variety of desert tribes that inhabited the remotest northern territories of Spain’s North American possessions. The attack took the Spanish by surprise. Outnumbered and overwhelmed, the remaining Spanish missionaries and settlers retreated hundreds of miles to the south, fleeing a burned out and utterly demolished disaster zone. The natives who rebelled celebrated, while those not participating in the uprising bided their time and knew that Spain would be back. Luis de Sáric and his men would only enjoy a temporary victory here.

What led up to the Pima Revolt of 1751 and in what context did it occur? The revolt took place in what the Spanish called Pimería Alta, or the upper Pima territory which encompassed the northern part of the modern-day Mexican state of Sonora and the southern half of the US state of Arizona. Pimería Alta was part of the Spanish province of Sonora y Sinaloa, which belonged to the greater colony of New Spain. Besides very infrequent visits by Spanish explorers and fortune-hunters, Pimería Alta was of little interest to Europeans until 1687 when the Italian Jesuit Eusebio Kino founded the mission of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de Cósari, in what is now northern Sonora. Father Kino would establish some 20 other missions and visitas and many small rancherías in the region, with his northernmost outpost at San Xavier del Bac, which is still a functioning church run by the Franciscans located just 10 miles south of Tucson. Father Kino was declared “Venerable” by Pope Francis on July 11, 2020, thus putting him on the road to sainthood. After Kino’s death in 1711, the missions of Pimería Alta came under the control of a series of despotic and cruel European Jesuits who had very little to no experience with frontier life in New Spain. The indigenous people of Pimería Alta grew to resent mission life and the encroaching Spanish settlements that followed in the wake of Father Kino’s death.

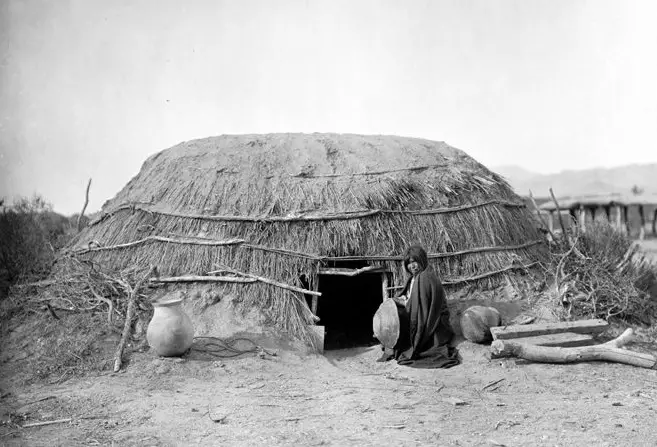

What indigenous groups called Pimería Alta home? The descendants of the original inhabitants of this region still call the area home. The territory was named after the Pima people, who call themselves the Akimel O’odham. At the time of the first Spanish contact the Pimas were living in villages along the rivers of what is now the central and southern parts of US state of Arizona and the northern part of the Mexican state of Sonora. Villages were comprised of familial housing clusters formed around a shared ramada and cooking area. There was no concept of central control or kingship among the O’odham peoples of Pimería Alta. The name Akimel O’odham literally means “The River People.” The word “Pima” comes from a phrase in the O’odham language pi mac which means “I don’t know,” and was frequently uttered by natives in the presence of the Spanish. The Pimas were related to another neighboring group in Pimería Alta with nearly the same language whom the Spanish called “Papago.” The Papago call themselves now – and have always called themselves – the Tohono O’odham, which means “The Desert People.” To the west of the Tohono O’odham, into the Gran Desierto de Altar in the northwestern part of the modern Mexican state of Sonora lived the Hia C-ed O’odham, also known as “The Sand Dune People.” Pimería Alta was also home to the more nomadic Apache tribes and what are now called the Colorado River Peoples in the far west of the territory. The more sedentary O’odham peoples lived a peaceful existence along the rivers, in the mountains and in the deserts of the region. The Pimas and related groups sometimes had to fight other tribes when resources became scarcer in the harsh desert environment, but they rarely engaged in war and had no traditional warrior culture. Resources in the area became more limited with the arrival of the missionaries and the Spanish settlers, however, which caused many native people in Pimería Alta to re-think the whole notion of “peaceful coexistence.” It was during the first decades of the 1700s that the Pima leader Oacpicagigua or Luis de Sáric emerged.

What indigenous groups called Pimería Alta home? The descendants of the original inhabitants of this region still call the area home. The territory was named after the Pima people, who call themselves the Akimel O’odham. At the time of the first Spanish contact the Pimas were living in villages along the rivers of what is now the central and southern parts of US state of Arizona and the northern part of the Mexican state of Sonora. Villages were comprised of familial housing clusters formed around a shared ramada and cooking area. There was no concept of central control or kingship among the O’odham peoples of Pimería Alta. The name Akimel O’odham literally means “The River People.” The word “Pima” comes from a phrase in the O’odham language pi mac which means “I don’t know,” and was frequently uttered by natives in the presence of the Spanish. The Pimas were related to another neighboring group in Pimería Alta with nearly the same language whom the Spanish called “Papago.” The Papago call themselves now – and have always called themselves – the Tohono O’odham, which means “The Desert People.” To the west of the Tohono O’odham, into the Gran Desierto de Altar in the northwestern part of the modern Mexican state of Sonora lived the Hia C-ed O’odham, also known as “The Sand Dune People.” Pimería Alta was also home to the more nomadic Apache tribes and what are now called the Colorado River Peoples in the far west of the territory. The more sedentary O’odham peoples lived a peaceful existence along the rivers, in the mountains and in the deserts of the region. The Pimas and related groups sometimes had to fight other tribes when resources became scarcer in the harsh desert environment, but they rarely engaged in war and had no traditional warrior culture. Resources in the area became more limited with the arrival of the missionaries and the Spanish settlers, however, which caused many native people in Pimería Alta to re-think the whole notion of “peaceful coexistence.” It was during the first decades of the 1700s that the Pima leader Oacpicagigua or Luis de Sáric emerged.

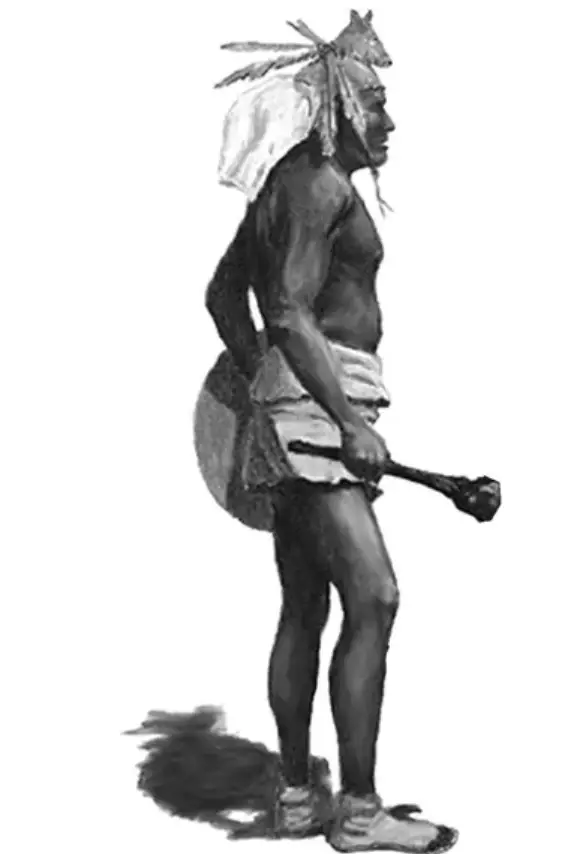

As a teenager Luis joined the Spanish in their wars against the desert-dwelling coastal Seri people, a group that still calls northwestern Sonora home. The Seri refused all contact with outsiders and fiercely resisted Spanish incursions in their territory. This led to a series of conflicts over many decades. For more about the Seris, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 209: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GCTFZJHl730 During the Seri campaigns Luis de Sáric honed his fighting skills and learned to strategize alongside some of Spain’s best military commanders at the time. The Pima contingent in the Seri Wars often had more success than the Spanish battalions and Spanish military officers noted Luis’ tactical and leadership skills. After the campaigns against the Seri ended, Luis was recognized more formally by the Spanish. The military authorities gave him a uniform and the rank of Captain-General, which was the equivalent of a military governor of a territory. The Spanish governor of the province of Sonora y Sinaloa, a man named Diego Ortiz Parrilla, even bestowed upon Luis de Sáric a fancy baton with a silver handle and afforded him special privileges and protections. While to the Spanish, the uniform, the title, and the baton seemed mostly symbolic, Luis took it all very  seriously and saw himself a sort of grand leader of all indigenous peoples of Pimería Alta. The Jesuit fathers and the rest of the mission clergy became concerned with the Spanish civil authorities giving Luis and other Pimas special powers and protections without consulting them. A padre of one of the Pimería Alta missions named Father Stiger wrote this in his diary in April of 1750, a year before the Pima Revolt of 1751: “The Governor told the Pimas that they would come to see their lands extend to the Rio Colorado. What we are seeing is that during the Seri campaign he flattered them greatly and they now return most haughty and averse to the Padres.” Although with a new sense of pride and self-importance, Luis de Sáric still did the bidding of the Spanish, and that included that of the civil and religious authorities. He encouraged the desert and dune-dwelling O’odham peoples to enter the mission system and the missions thus gained hundreds of new converts. As he had worked closely with the Spanish in military and missionary capacities, Luis de Sáric saw many vulnerabilities among the newcomers to his ancestral lands. For one, the Spanish army was spread out over a vast territory with presidios and other outposts staffed with sometimes little more than a dozen men. Also, the padres in the missions were at odds with the Spanish governmental authorities. In the years after Father Kino’s death, the mission system in Pimería Alta turned into something likened to a feudal system with individual padres running their missions and their surrounding lands like medieval lords. Brutality was common in the missions and many indigenous people who had gone into the mission system with open hearts expecting a better way of life were treated as little more than slaves to increase the wealth and power of the Jesuit fathers. A particularly autocratic padre was Father Ignacio Keller who was ethnically German and came to Pimería Alta directly from Moravia, now part of the Czech Republic. He was the head of the mission at Suamca. Luis de Sáric rode through Suamca on his way to the Presidio of San Felipe to join Spanish soldiers in their campaign against the Apache who had been raiding Spanish mining camps and other small settlements on the Pimería Alta frontier. When Father Keller saw Luis on a horse dressed in his Spanish captain-general uniform and carrying his silver-tipped baton, the padre laughed and had some things to say about the unusual scene. Father Keller said that Luis would probably be best suited to using native bows and arrows and said that he should probably trade the army uniform for coyote skins and a loincloth. Luis de Sáric did not respond kindly to the insults and Father Keller continued. The German Jesuit called the native leader a Chichimeca dog who was best suited to hunt rabbits and rodents in the hills. That was the last straw for the proud Luis. He quit the Apache campaign and went back home, and according to one historian he “nursed dark thoughts.” Luis would use what he knew of the Spanish weaknesses to drive the invaders out of his homeland, or so was the plan.

seriously and saw himself a sort of grand leader of all indigenous peoples of Pimería Alta. The Jesuit fathers and the rest of the mission clergy became concerned with the Spanish civil authorities giving Luis and other Pimas special powers and protections without consulting them. A padre of one of the Pimería Alta missions named Father Stiger wrote this in his diary in April of 1750, a year before the Pima Revolt of 1751: “The Governor told the Pimas that they would come to see their lands extend to the Rio Colorado. What we are seeing is that during the Seri campaign he flattered them greatly and they now return most haughty and averse to the Padres.” Although with a new sense of pride and self-importance, Luis de Sáric still did the bidding of the Spanish, and that included that of the civil and religious authorities. He encouraged the desert and dune-dwelling O’odham peoples to enter the mission system and the missions thus gained hundreds of new converts. As he had worked closely with the Spanish in military and missionary capacities, Luis de Sáric saw many vulnerabilities among the newcomers to his ancestral lands. For one, the Spanish army was spread out over a vast territory with presidios and other outposts staffed with sometimes little more than a dozen men. Also, the padres in the missions were at odds with the Spanish governmental authorities. In the years after Father Kino’s death, the mission system in Pimería Alta turned into something likened to a feudal system with individual padres running their missions and their surrounding lands like medieval lords. Brutality was common in the missions and many indigenous people who had gone into the mission system with open hearts expecting a better way of life were treated as little more than slaves to increase the wealth and power of the Jesuit fathers. A particularly autocratic padre was Father Ignacio Keller who was ethnically German and came to Pimería Alta directly from Moravia, now part of the Czech Republic. He was the head of the mission at Suamca. Luis de Sáric rode through Suamca on his way to the Presidio of San Felipe to join Spanish soldiers in their campaign against the Apache who had been raiding Spanish mining camps and other small settlements on the Pimería Alta frontier. When Father Keller saw Luis on a horse dressed in his Spanish captain-general uniform and carrying his silver-tipped baton, the padre laughed and had some things to say about the unusual scene. Father Keller said that Luis would probably be best suited to using native bows and arrows and said that he should probably trade the army uniform for coyote skins and a loincloth. Luis de Sáric did not respond kindly to the insults and Father Keller continued. The German Jesuit called the native leader a Chichimeca dog who was best suited to hunt rabbits and rodents in the hills. That was the last straw for the proud Luis. He quit the Apache campaign and went back home, and according to one historian he “nursed dark thoughts.” Luis would use what he knew of the Spanish weaknesses to drive the invaders out of his homeland, or so was the plan.

The strategizing for what would be known to history as the Pima Revolt of 1751 took months. Luis de Sáric, aka Oacpicagigua, had to rally people from various native groups to his cause. Many indigenous people in and out of the mission system had comfortable lives and were satisfied with the way things were. Many were wary of someone so boastful and egotistical as Luis and some accused of him of being too “Spanish.” He had a harder time recruiting than he thought, but over the months prior to the November 20, 1751 offensive, he had assembled an army of over 2,000 from various indigenous groups ranging all the way to the Colorado River. Luis’s strategy was to divide the new native army into several groups to attack several missions and military installations all at once, thus astonishing the unprepared Spaniards and causing them to abandon their settlements and ultimately the region. On the night of November 20th, the plan seemed to have been working. Most of the Spanish infrastructure had been burned to the ground, but the killing seemed to have been too indiscriminate and many people were killed by Luis’ battalions who were not Spanish or loyal to Spain. History records many innocent O’odham people at the missions who were killed mercilessly, as well as children of Spanish settlers and Afro-Mexican slaves who were bonded servants to the padres. The wholesale slaughter of all people did not go over well in a land full of divided loyalties. Luis found it very difficult to hold on to the territory after he had thoroughly scorched it and many knew the Spanish would return.

The strategizing for what would be known to history as the Pima Revolt of 1751 took months. Luis de Sáric, aka Oacpicagigua, had to rally people from various native groups to his cause. Many indigenous people in and out of the mission system had comfortable lives and were satisfied with the way things were. Many were wary of someone so boastful and egotistical as Luis and some accused of him of being too “Spanish.” He had a harder time recruiting than he thought, but over the months prior to the November 20, 1751 offensive, he had assembled an army of over 2,000 from various indigenous groups ranging all the way to the Colorado River. Luis’s strategy was to divide the new native army into several groups to attack several missions and military installations all at once, thus astonishing the unprepared Spaniards and causing them to abandon their settlements and ultimately the region. On the night of November 20th, the plan seemed to have been working. Most of the Spanish infrastructure had been burned to the ground, but the killing seemed to have been too indiscriminate and many people were killed by Luis’ battalions who were not Spanish or loyal to Spain. History records many innocent O’odham people at the missions who were killed mercilessly, as well as children of Spanish settlers and Afro-Mexican slaves who were bonded servants to the padres. The wholesale slaughter of all people did not go over well in a land full of divided loyalties. Luis found it very difficult to hold on to the territory after he had thoroughly scorched it and many knew the Spanish would return.

The revolt continued into the next year. On January 5, 1752, near the modern-day Arizona town of Arivaca, nearly 2,000 natives under the command of Luis de Sáric attacked 86 Spanish soldiers who had regrouped near the demolished visita, or stopover, located there. The native force was defeated, and Luis’ troops were demoralized. The governor of the province of Sonora y Sinaloa, once sympathetic enough to the Pimas to have given Luis the famous silver-tipped baton, called for the rebels’ capture and execution. Luis and his men retreated to the mountains to come up with a new plan, but the Pima leader’s charisma could not save him. Many of his fighters deserted, and other natives refused to join his cause. Luis sent a delegation to try to recruit the Chiricahua Apache, known for their zeal in raiding Spanish settlements, but the Apache leaders turned the Pima delegation away. Luis and his hundred or so followers then retreated north to the Catalina Mountains overlooking modern-day Tucson. The revolt seemed all but finished. On March 18, 1752 the great Pima leader arrived at the mission at Tubac, got off his horse, fell to his knees pledging loyalty to His Majesty King Ferdinand the Sixth of Spain, and humbly asked for mercy. The Spanish governor who was once his ally had been transferred to another post and could not advocate for him. Luis had also lost face with his own people and few Pimas had respect for him. He was arrested and died in prison in May of 1753 after an attempted suicide. The mission system continued, and the Spanish presence increased. Pimería Alta never again had an uprising like the one of 1751, and despite the long odds and many obstacles, the O’odham people continue to survive and thrive well into the 21st Century.

REFERENCES

National Parks Service online brochure about Tumacácori: https://www.nps.gov/tuma/learn/historyculture/luis-oacpicgigua-alias-luis-of-saric.htm