Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

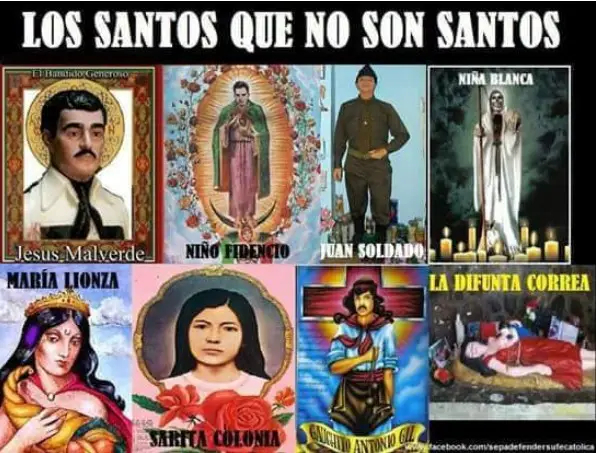

In March of 2023 a monsignor in Mexico City issued a colorful flyer that soon had widespread distribution on the internet. The flyer was called “Los Santos que no son santos,” or in English, “The saints that are not saints” and it warned “good Catholics” not to get caught up in idolatry or “false veneration.” The full-color flyer had images familiar to most Mexicans. Number one on the forbidden list was Jesus Malverde, discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 7 https://mexicounexplained.com/jesus-malverde-rogue-or-saint/ . Beside him was the Niño Fidencio, who was the topic of Mexico Unexplained episode 60 https://mexicounexplained.com/el-nino-fidencio-miraculous-healer-fake/ . The third one on the list was the famous folk saint of Tijuana, Juan Soldado whose life and miracles were examined in Mexico Unexplained episode number 143 https://mexicounexplained.com/juan-soldado-folk-saint-of-migrants-and-the-wrongly-accused/ . Alongside the martyr from Tijuana on this flyer of forbidden saints was none other than the Santa Muerte or Santisima Muerte, also known as the Niña Blanca, discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 9 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-santa-muerte-death-respected/ . Below Jesus Malverde was a somewhat unfamiliar image. The image is that of a voluptuous woman in a red cape. She has long black hair and is wearing a golden crown. She holds a cornucopia or horn of plenty full of tropical fruits. She is María Lionza and is relatively new among the pantheon of Mexico’s forbidden folk saints not recognized by the Catholic Church. She is said to represent love, peace, harmony, kindness, happiness, and abundance. Icons and statues dedicated to María Lionza have been popping up in the urban areas of Mexico just in the past 5 years or so and devotion to her is on the rise.

In March of 2023 a monsignor in Mexico City issued a colorful flyer that soon had widespread distribution on the internet. The flyer was called “Los Santos que no son santos,” or in English, “The saints that are not saints” and it warned “good Catholics” not to get caught up in idolatry or “false veneration.” The full-color flyer had images familiar to most Mexicans. Number one on the forbidden list was Jesus Malverde, discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 7 https://mexicounexplained.com/jesus-malverde-rogue-or-saint/ . Beside him was the Niño Fidencio, who was the topic of Mexico Unexplained episode 60 https://mexicounexplained.com/el-nino-fidencio-miraculous-healer-fake/ . The third one on the list was the famous folk saint of Tijuana, Juan Soldado whose life and miracles were examined in Mexico Unexplained episode number 143 https://mexicounexplained.com/juan-soldado-folk-saint-of-migrants-and-the-wrongly-accused/ . Alongside the martyr from Tijuana on this flyer of forbidden saints was none other than the Santa Muerte or Santisima Muerte, also known as the Niña Blanca, discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 9 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-santa-muerte-death-respected/ . Below Jesus Malverde was a somewhat unfamiliar image. The image is that of a voluptuous woman in a red cape. She has long black hair and is wearing a golden crown. She holds a cornucopia or horn of plenty full of tropical fruits. She is María Lionza and is relatively new among the pantheon of Mexico’s forbidden folk saints not recognized by the Catholic Church. She is said to represent love, peace, harmony, kindness, happiness, and abundance. Icons and statues dedicated to María Lionza have been popping up in the urban areas of Mexico just in the past 5 years or so and devotion to her is on the rise.

The title of this episode is “María Lionza: Mexico’s Imported Indigenous Folk Saint,” which begs the question: How can an indigenous saint be imported? The answer is that María Lionza was an indigenous woman who lived in Venezuela and her veneration began there. The 2020 Mexican census showed that Venezuelans made up the third largest immigrant group in Mexico behind Guatemalans and Americans. Statistics show that legal immigrants from Venezuela and their descendants number over 50,000 in Mexico. Demographers estimate that there could be over 10,000 more Venezuelans living in Mexico illegally with most of the immigration – both legal and illegal – happening within the last 15 years. The 60,000+ Venezuelans have brought their culture with them and that includes aspects of their folk religious beliefs. As culture is shared, some people in their new land have shown interest in this intriguing and powerful saint called María Lionza, and her following is growing in Mexico among non-Venezuelans. So, who is María Lionza and what is her story?

Like so many belief systems, or stories within those systems, there is more than one narrative of María Lionza’s origins. In the most popular story, she is the daughter of an indigenous chief who ruled in what is now the state of Yaracuy in the central-western region of Venezuela. At birth, María Lionza’s name was Yara, and when she was old enough to live on her own, her father sent her to live on Sorte Mountain until he was able to find a suitable husband for her. While drinking from a mountain stream, María Lionza was attacked by a gigantic anaconda that swallowed her whole. In this version of the story, she was still alive inside the huge serpent, and she asked the mountain for help. The spirits of the mountain freed her from the snake, but María disintegrated and thus became part of Sorte Mountain. This is why the mountain today is a pilgrimage spot for those believing in María Lionza, people who call themselves the “lionceros.” This first version of the origins of this folk saint has a slight variation: Instead of dissolving into the mountain, the mountain spirits made the anaconda explode and its remains rained down on the land, thus giving an explanation for the region’s torrential rainstorms. The second version of the María Lionza origin story has her as the daughter of a powerful indigenous chief and a European woman who was either captured by the natives or was shipwrecked. María’s mother died in childbirth. The European woman was very fair, and this is why María Lionza is often depicted as having lighter skin and light eyes mixed with some indigenous features. In this origin story, María went to Sorte Mountain as a young girl and at the side of a mountain stream, instead of being attacked by a snake, she saw her reflection in the water for the first time. When she saw that her eyes were green and so much different from the rest of her people, she realized that she was unique and decided to ask the mountain to help her become a shamanic leader. In either story, María Lionza worked many miracles during her long life and after death she became more powerful and people began to worship her. In early Spanish colonial days, her indigenous name of Yara transformed into “Santa María de la Onza,” or, loosely translated into English, “Saint Mary of the Wildcat.” For hundreds of years the Catholic Church looked the other way as a region of Venezuela had their old feminine spirit Yara take on aspects of the Virgin Mary. As a santo closely associated with nature and often depicted among wild animals, the forest wildcat, known in South America as “la onza” became part of her name. Over time, “La Onza” contracted to one word, “Lionza,” and so she became known as Santa María Lionza.

Like so many belief systems, or stories within those systems, there is more than one narrative of María Lionza’s origins. In the most popular story, she is the daughter of an indigenous chief who ruled in what is now the state of Yaracuy in the central-western region of Venezuela. At birth, María Lionza’s name was Yara, and when she was old enough to live on her own, her father sent her to live on Sorte Mountain until he was able to find a suitable husband for her. While drinking from a mountain stream, María Lionza was attacked by a gigantic anaconda that swallowed her whole. In this version of the story, she was still alive inside the huge serpent, and she asked the mountain for help. The spirits of the mountain freed her from the snake, but María disintegrated and thus became part of Sorte Mountain. This is why the mountain today is a pilgrimage spot for those believing in María Lionza, people who call themselves the “lionceros.” This first version of the origins of this folk saint has a slight variation: Instead of dissolving into the mountain, the mountain spirits made the anaconda explode and its remains rained down on the land, thus giving an explanation for the region’s torrential rainstorms. The second version of the María Lionza origin story has her as the daughter of a powerful indigenous chief and a European woman who was either captured by the natives or was shipwrecked. María’s mother died in childbirth. The European woman was very fair, and this is why María Lionza is often depicted as having lighter skin and light eyes mixed with some indigenous features. In this origin story, María went to Sorte Mountain as a young girl and at the side of a mountain stream, instead of being attacked by a snake, she saw her reflection in the water for the first time. When she saw that her eyes were green and so much different from the rest of her people, she realized that she was unique and decided to ask the mountain to help her become a shamanic leader. In either story, María Lionza worked many miracles during her long life and after death she became more powerful and people began to worship her. In early Spanish colonial days, her indigenous name of Yara transformed into “Santa María de la Onza,” or, loosely translated into English, “Saint Mary of the Wildcat.” For hundreds of years the Catholic Church looked the other way as a region of Venezuela had their old feminine spirit Yara take on aspects of the Virgin Mary. As a santo closely associated with nature and often depicted among wild animals, the forest wildcat, known in South America as “la onza” became part of her name. Over time, “La Onza” contracted to one word, “Lionza,” and so she became known as Santa María Lionza.

Over the centuries that she has been venerated, this localized indigenous mountain spirit grew more popular throughout Venezuela and merged with elements of Catholicism and west African religions brought to the Americas by enslaved people. By the late 1800s, the followers of María Lionza also adopted elements of European and North American spiritism, as this tradition began to move into the urban areas and started to permeate higher socio-economic classes. The religious traditions surrounding the adoration of María Lionza are now a mish-mash of various beliefs, customs and cultural perspectives. Scholars refer to this as syncretism.

In the Universe over which María Lionza presides as “La Reina,” or “The Queen,” she is one of what the Venezuelans call the “Tres Potencias,” or “Three Powerful Ones.” By her side, but having less power, are two formidable and influential spirits called Guaicaipuro and Negro Felipe who are both based on historical figures. Guaicaipuro is the spirit of a 16th Century leader of the Teques and Caracas tribes. He led a coalition of indigenous people which revolted against the Spanish but he was ultimately killed by conquistador Francisco de Infante in the year 1568. The other potencia seen on María Lionza’s side, Negro Felipe, is based on a combination of real-life men of African descent. He is said to be a blend of two people: Pedro Camejo, known to history as “Primero Negro” and a man named Negro Miguel. Camejo was a slave who earned his freedom by fighting with Simón Bolívar during Venezuela’s war of independence. Negro Miguel is often called Rey Miguel, or King Miguel. He led the first successful slave revolt in Venezuela’s history and ruled a small independent kingdom in the wilds of Venezuela called Buria from 1552 to 1555. As warrior spirits, both Negro Felipe and Guaicaipuro are thought to give balance to María Lionza’s femininity while also providing a sense of what modern people would call “equity” by representing different races. In this different take on the Trinity it is clear that María Lionza is the one who is the most powerful and most revered of the Tres Potencias and Negro Felipe and Guaicaipuro are seen as strong supporters. María Lionza and the other potencias preside over different “courts” or groupings of saints and spirits. This is where the María Lionza devotion shows its Afro-Venezuelan roots as is very similar to other syncretic or blended African-based spiritual movements found in the Americas such as Santería, Candomblé and Macumba. Some of the most popular groupings or “courts” of saints include indigenous, African, freedom fighters and Viking. In the María Lionza system of beliefs even the spirit of Eric the Red, the Viking who discovered Greenland, can be called upon to help in this world. These courts of santos are populated by a wide number of people who were once alive from a drug cartel leader who was seen as a Robin Hood figure to some of Venezuela’s ex-presidents. Although prayers and offerings can be made to the spirits in the courts, everything flows up through María Lionza.

In the Universe over which María Lionza presides as “La Reina,” or “The Queen,” she is one of what the Venezuelans call the “Tres Potencias,” or “Three Powerful Ones.” By her side, but having less power, are two formidable and influential spirits called Guaicaipuro and Negro Felipe who are both based on historical figures. Guaicaipuro is the spirit of a 16th Century leader of the Teques and Caracas tribes. He led a coalition of indigenous people which revolted against the Spanish but he was ultimately killed by conquistador Francisco de Infante in the year 1568. The other potencia seen on María Lionza’s side, Negro Felipe, is based on a combination of real-life men of African descent. He is said to be a blend of two people: Pedro Camejo, known to history as “Primero Negro” and a man named Negro Miguel. Camejo was a slave who earned his freedom by fighting with Simón Bolívar during Venezuela’s war of independence. Negro Miguel is often called Rey Miguel, or King Miguel. He led the first successful slave revolt in Venezuela’s history and ruled a small independent kingdom in the wilds of Venezuela called Buria from 1552 to 1555. As warrior spirits, both Negro Felipe and Guaicaipuro are thought to give balance to María Lionza’s femininity while also providing a sense of what modern people would call “equity” by representing different races. In this different take on the Trinity it is clear that María Lionza is the one who is the most powerful and most revered of the Tres Potencias and Negro Felipe and Guaicaipuro are seen as strong supporters. María Lionza and the other potencias preside over different “courts” or groupings of saints and spirits. This is where the María Lionza devotion shows its Afro-Venezuelan roots as is very similar to other syncretic or blended African-based spiritual movements found in the Americas such as Santería, Candomblé and Macumba. Some of the most popular groupings or “courts” of saints include indigenous, African, freedom fighters and Viking. In the María Lionza system of beliefs even the spirit of Eric the Red, the Viking who discovered Greenland, can be called upon to help in this world. These courts of santos are populated by a wide number of people who were once alive from a drug cartel leader who was seen as a Robin Hood figure to some of Venezuela’s ex-presidents. Although prayers and offerings can be made to the spirits in the courts, everything flows up through María Lionza.

María Lionza’s official feast day is October 12th. On that day, people make pilgrimages to Sorte Mountain in Venezuela, and in recent years, many Mexican devotees have been making this annual pilgrimage. People had been going to the mountain for centuries to show respect to the folk saint or to tap into her power but in the early 20th Century a man named Lino Valles built the first roads  to the mountain. Today, Valles is seen as the first apostle of María Lionza. He has his own statues and rituals dedicated to him in the context of this folk religion. Along the pilgrimage route are what are called perfumerias, little esoteric shops that sell spiritual supplies to the lionceros. As an aside, some of the articles at these shops can now be found at botanicas in some major Mexican cities. On the mountain, many ceremonies take place conducted by materias, or mediums, who channel spirits. Materias are exclusively men. After dark and by candlelight, the public gathers around as the mediums take on the spirit of an old Norse warrior or an African chief. The materias also conduct ceremonies to bless or cleanse participants which may include spraying them with alcoholic beverages from their mouths or asking them to lie in a circle of candles while they chant unintelligible prayers. While some of these rites may seem like “black magic” or may be called “satanic” by outsiders, followers will be quick to say that María Lionza represents love, abundance, balance and hope for a brighter future. There is no evil connected with her.

to the mountain. Today, Valles is seen as the first apostle of María Lionza. He has his own statues and rituals dedicated to him in the context of this folk religion. Along the pilgrimage route are what are called perfumerias, little esoteric shops that sell spiritual supplies to the lionceros. As an aside, some of the articles at these shops can now be found at botanicas in some major Mexican cities. On the mountain, many ceremonies take place conducted by materias, or mediums, who channel spirits. Materias are exclusively men. After dark and by candlelight, the public gathers around as the mediums take on the spirit of an old Norse warrior or an African chief. The materias also conduct ceremonies to bless or cleanse participants which may include spraying them with alcoholic beverages from their mouths or asking them to lie in a circle of candles while they chant unintelligible prayers. While some of these rites may seem like “black magic” or may be called “satanic” by outsiders, followers will be quick to say that María Lionza represents love, abundance, balance and hope for a brighter future. There is no evil connected with her.

The devotion to María Lionza has increased exponentially over the years. As seen in devotions to other folk saints, people will turn to the unconventional when they feel like traditional institutions have failed them. In Venezuela, the government is seen as a failure and the Catholic Church is doing little to relieve the misery of millions of people. The Venezuelans in Mexico have transplanted their powerful symbol of love and hope into new soil, and in this new country the devotion to María Lionza is growing. Sometime in 2024 a pilgrimage site to this imported indigenous folk saint is planned for someplace in the mountains outside Mexico City which will serve as a proxy for Sorte Mountain in Venezuela, the original home of the young indigenous woman named Yara who became a saint. Perhaps in 10 years’ time, or maybe sooner, María Lionza will occupy a very prominent position among Mexico’s pantheon of alternative religions.

REFERENCES

Varner, Gary. María Lionza: An Indigenous Goddess of Venezuela. Lulu.com, 2007. We are Amazon affiliates. To purchase the book on Amazon, go here: https://amzn.to/3JKHV4U