Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

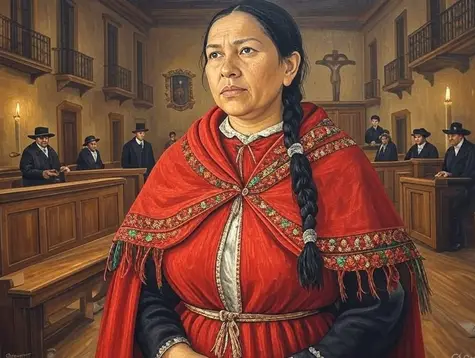

In the late 18th century, a woman named María Joaquina Uchu Túpac Inca Yupanqui emerged in Mexico City, claiming descent from the Inca emperors of Peru and seeking formal recognition of her noble status from Spanish colonial authorities. Born circa 1755 and active in New Spain during a period of shifting imperial policies, María Joaquina represents a fascinating intersection of Indigenous heritage and colonial adaptation. Her legal petition, initiated in 1787 and culminating in a royal pension in 1799, underscores the persistence of pre-Columbian noble lineages in the Spanish Americas long after the conquests of the 16th century. This episode will examine her life as a lens into the experiences of Indigenous elites under colonial rule, focusing on her genealogical claims, legal strategies, and integration into pre-independence Mexican society. Far from a mere curiosity, María Joaquina’s story illuminates the complex dynamics of identity, gender, and power in late colonial New Spain.

In the late 18th century, a woman named María Joaquina Uchu Túpac Inca Yupanqui emerged in Mexico City, claiming descent from the Inca emperors of Peru and seeking formal recognition of her noble status from Spanish colonial authorities. Born circa 1755 and active in New Spain during a period of shifting imperial policies, María Joaquina represents a fascinating intersection of Indigenous heritage and colonial adaptation. Her legal petition, initiated in 1787 and culminating in a royal pension in 1799, underscores the persistence of pre-Columbian noble lineages in the Spanish Americas long after the conquests of the 16th century. This episode will examine her life as a lens into the experiences of Indigenous elites under colonial rule, focusing on her genealogical claims, legal strategies, and integration into pre-independence Mexican society. Far from a mere curiosity, María Joaquina’s story illuminates the complex dynamics of identity, gender, and power in late colonial New Spain.

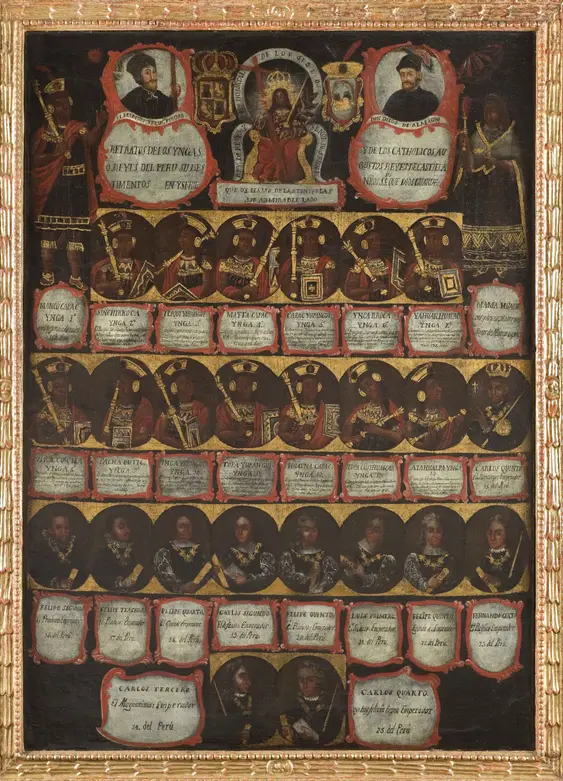

First, some historical context. The Inca Empire, once spanning much of western South America, fell to Spanish forces in 1533 with the execution of Emperor Atahualpa. Yet, the legacy of its ruling class endured through descendants who navigated the new colonial order. Following the Spanish conquest, Francisco Pizarro and subsequent viceroys recognized certain Inca nobles as allies, granting them specific privileges under Spanish law. King Philip the Second’s 1545 decree, for instance, extended mercedes reales—royal favors—to figures like Felipe Túpac Inca Yupanqui and Gonzalo Uchu Hualpa, whom María Joaquina later cited as ancestors. These privileges included land, tribute exemptions, noble titles, and sometimes even pensions, reflecting Spain’s strategy of co-opting Indigenous elites to stabilize colonial governance.

By the 18th century, however, the Bourbon Reforms initiated throughout the Spanish Empire tightened economic control and reduced the autonomy of indigenous elite lineages. In Peru, the 1780 rebellion of Túpac Amaru the Second—a self-proclaimed descendant of the Inca Empire’s rulers—highlighted the tensions between Indigenous nobility and colonial authorities, prompting harsher oversight by Spain. Meanwhile, some Inca descendants migrated beyond Peru, including to New Spain, where they leveraged legal mechanisms to assert their status. María Joaquina’s arrival in Mexico reflects this broader diaspora, situating her within a network of displaced elites seeking to preserve their heritage amid Spanish imperial transformation.

By the 18th century, however, the Bourbon Reforms initiated throughout the Spanish Empire tightened economic control and reduced the autonomy of indigenous elite lineages. In Peru, the 1780 rebellion of Túpac Amaru the Second—a self-proclaimed descendant of the Inca Empire’s rulers—highlighted the tensions between Indigenous nobility and colonial authorities, prompting harsher oversight by Spain. Meanwhile, some Inca descendants migrated beyond Peru, including to New Spain, where they leveraged legal mechanisms to assert their status. María Joaquina’s arrival in Mexico reflects this broader diaspora, situating her within a network of displaced elites seeking to preserve their heritage amid Spanish imperial transformation.

Details of María Joaquina’s early life remain sparse which is a common challenge in reconstructing the biographies of colonial Indigenous figures. She was likely born around 1755, possibly in Lima, Peru, a major administrative center of the Viceroyalty of Peru where Inca nobles maintained a presence. Her father, Miguel Uchu Inca, claimed descent from Huayna Capac, the last pre-conquest Sapa Inca, or supreme emperor of the Inca Empire. Miguel Uchu Inca traveled with María Joaquina and her brother to New Spain. The family’s relocation may have been driven by economic opportunity or political instability in Peru, though the precise motivations are lost to history. Miguel’s other sons followed the rest of the family to Mexico City a few years later.

Archival records indicate that Miguel Uchu Inca died during a trip to Europe, leaving María Joaquina and her siblings to establish lives for themselves on their own in Mexico City. This transition marked the beginning of María’s independent engagement with colonial society. Unlike the sensational narratives sometimes attached to such figures, her story lacks dramatic flourishes; instead, it reveals a pragmatic effort to secure a stable foothold in a new environment. By the 1780s, María Joaquina was a notable resident of the viceregal capital, poised to assert her inherited status in a context far removed from the Andes.

In 1787, María Joaquina initiated a formal petition to the Spanish Crown, seeking recognition of her noble lineage and the privileges tied to it. Her prueba de nobleza—a proof of nobility—claimed she was a fifth-generation descendant of Huayna Capac and Túpac Inca Yupanqui, supported by genealogical charts and textual evidence preserved in colonial archives. The documentation María presented to the courts was rather thorough, including everything from pension records to formal papers outlining exact services her ancestors provided to the Spanish Crown. She invoked the 1545 decree from the Spanish king Philip the Second, arguing that her ancestors’ rights extended to her as a legitimate heir. Following her brothers’ deaths, she assumed leadership of the family’s claim, a role that underscores her agency in a patriarchal legal system.

In 1787, María Joaquina initiated a formal petition to the Spanish Crown, seeking recognition of her noble lineage and the privileges tied to it. Her prueba de nobleza—a proof of nobility—claimed she was a fifth-generation descendant of Huayna Capac and Túpac Inca Yupanqui, supported by genealogical charts and textual evidence preserved in colonial archives. The documentation María presented to the courts was rather thorough, including everything from pension records to formal papers outlining exact services her ancestors provided to the Spanish Crown. She invoked the 1545 decree from the Spanish king Philip the Second, arguing that her ancestors’ rights extended to her as a legitimate heir. Following her brothers’ deaths, she assumed leadership of the family’s claim, a role that underscores her agency in a patriarchal legal system.

The petition process, spanning from 1787 to 1799, involved extensive documentation and scrutiny by colonial officials in both Mexico City and in the Viceroyalty of Peru. María Joaquina presented a coat of arms blending Inca and Spanish symbols—crimson tassels alongside helmets and castles—illustrating her strategic fusion of identities. Her case navigated the Bourbon-era emphasis on centralized authority, which often viewed Indigenous nobility with skepticism. Yet, her persistence paid off: in 1799, twelve years after she started her legal proceedings, she secured a royal pension of 300 pesos annually. This was a partial victory that affirmed her status without fully restoring the extensive privileges and wealth of earlier generations.

This legal effort highlights the adaptability of Indigenous elites, who used Spanish institutions to negotiate their place in colonial society. Unlike Túpac Amaru the Second’s armed rebellion in Peru, María Joaquina’s approach reflects a quieter form of resistance—one rooted in slow and systematic uses of documentation and dialogue rather than confrontation and violence.

María Joaquina’s life in Mexico City extended beyond her legal pursuits, revealing her integration into the colonial urban society of New Spain. She married twice, first to Juan Sánchez de Rojas, a minor official of the Holy Office of the Inquisition who could trace his lineage back to the early days of the Spanish Conquest in Mexico. With Sánchez de Rojas, María had three children. After Sánchez’s death, she wed Agustín de Estrada, a union that further embedded her in local networks and elite social circles. These marriages were strategic alliances and suggest a deliberate alignment with Spanish colonial structures. These unions enhanced María’s social standing while maintaining her Inca identity.

María Joaquina’s life in Mexico City extended beyond her legal pursuits, revealing her integration into the colonial urban society of New Spain. She married twice, first to Juan Sánchez de Rojas, a minor official of the Holy Office of the Inquisition who could trace his lineage back to the early days of the Spanish Conquest in Mexico. With Sánchez de Rojas, María had three children. After Sánchez’s death, she wed Agustín de Estrada, a union that further embedded her in local networks and elite social circles. These marriages were strategic alliances and suggest a deliberate alignment with Spanish colonial structures. These unions enhanced María’s social standing while maintaining her Inca identity.

Her residence in Mexico City, a bustling metropolis of diverse populations, placed her among other Indigenous nobles, such as descendants of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma, who similarly sought recognition from the Crown. Yet, María Joaquina’s status as an outsider from Peru distinguished her, requiring her to forge connections in a new cultural landscape. Her children’s fates are less documented, but their existence points to a legacy that bridged Inca heritage with colonial society in New Spain, a story that seems to complicate simplistic narratives of cultural erasure. There is no indication that María’s children ever relocated to Peru and most likely descendants of this Inca princess still live in parts of modern-day Mexico to this day. Modern Mexicans and Mexican-Americans might find it surprising when DNA tests reveal a minor portion of Andean ancestry, as the extent of the Inca diaspora across distant regions of the Spanish Empire is not widely known.

María Joaquina’s story offers valuable insights into the negotiation of Indigenous identity under colonial rule. Her claim to Inca nobility, validated through Spanish legal channels, exemplifies what scholars term “hidalguía indigena” which is a hybrid nobility that merged pre-Columbian prestige with European conventions. This hybrid nobility challenges often simplistic binary views of “colonizer” and “colonized” coming from mostly leftist/Marxist 21st Century academic circles and reveals more of a spectrum of agency among Indigenous elites in the Spanish colonies of the Americas.

María Joaquina’s story offers valuable insights into the negotiation of Indigenous identity under colonial rule. Her claim to Inca nobility, validated through Spanish legal channels, exemplifies what scholars term “hidalguía indigena” which is a hybrid nobility that merged pre-Columbian prestige with European conventions. This hybrid nobility challenges often simplistic binary views of “colonizer” and “colonized” coming from mostly leftist/Marxist 21st Century academic circles and reveals more of a spectrum of agency among Indigenous elites in the Spanish colonies of the Americas.

María Joaquina’s gender further enriches this narrative. As a woman leading her family’s legal efforts after her brothers’ deaths, this displaced Inca princess defied traditional expectations, aligning with other Indigenous noblewomen—like Beatriz Clara Coya in Peru—who asserted familial rights in colonial courts. María’s success, though limited, underscores the potential for women to influence colonial power dynamics, a theme often overshadowed by male-centric histories.

Within the context of late 18th-century New Spain, María’s petitions coincided with the Bourbon Reforms, which sought to streamline governance and extract greater revenue from colonial subjects. The Crown’s willingness to grant her a pension, however modest, suggests a lingering recognition of Indigenous nobility as a stabilizing force, even as broader policies marginalized such groups. Compared to the violent upheaval of Túpac Amaru the Second’s rebellion in her native Peru, María Joaquina’s approach illustrates a divergent strategy for preserving heritage: one that prioritized adaptation over resistance.

María’s legacy extends beyond her lifetime, contributing to historical understandings of the Inca diaspora and its reach into Mexico. While she did not spark a movement or leave a prominent lineage in the historical record, her case preserves a snapshot of Indigenous resilience. It invites reflection on how pre-Columbian identities persisted, reshaped by the colonial encounter, and how individuals like María Joaquina navigated this transformation.

María Joaquina Uchu Túpac Inca Yupanqui stood as a bridge between the Inca past and her colonial present of New Spain. Her life, marked by a determined pursuit of noble recognition, reflects the enduring significance of pre-conquest native heritage in the Americas. Through her legal victories, marriages, and integration into Mexico City’s society, she embodied the complexities of identity in a colonial world—neither fully assimilated nor wholly detached from her roots. For modern day people, her story offers a measured, evidence-based exploration of an Inca noblewoman’s journey to Mexico, illuminating the interplay of heritage, law, and survival in the late 18th century. Her pension of 300 pesos, secured in 1799, was more than a financial gain; it was a testament to the persistence of an Indigenous elite navigating the currents of empire.

REFERENCES

Quispe-Agnoli, Rocío. “Nobleza Andina y Escritura: La Construcción de la Identidad en el Virreinato del Perú (Siglos XVI-XVIII).” Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 25, no. 3, 2016, pp. 321–345.

Ramos, Gabriela, and Yanna Yannakakis, editors. Indigenous Intellectuals: Knowledge, Power, and Colonial Culture in Mexico and the Andes. Duke University Press, 2014.