Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In February of 1881 Swiss-American archaeologist Adolph Bandelier left Cochití Pueblo in New Mexico for points south. Sponsored by the Archaeological Institute, he was to join the Lorillard Expedition headed by famous French anthropologist Désiré Charnay which was exploring major ruins in central Mexico. When the eager Bandelier arrived in Mexico City, he had found that Charnay had already left for France. Disappointed, Bandelier made the best of it and got the okay from his backers to explore the ancient ruins by himself. He spent 6 months doing so. He started in Cholula and spent months surveying the gigantic pyramid at the site described in Mexico Unexplained episode number 26: https://mexicounexplained.com/cholula-largest-pyramid-world/ From here Bandelier went to Mitla and then to the site of Tlacolula with his final destination being the gigantic pre-Hispanic city of Monte Albán located in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. He would return to the States in March of 1882 and would publish the first account in English about these mysterious ruins in 1884 in an Archaeological Institute paper titled “An Archaeological Tour in Mexico in 1881.” Interest in this site was sporadic in the coming decades with intensive study only beginning in the 1930s by the Mexicans and then resuming in the 1960s by the Americans. Today, Monte Albán is seen as one of the most important ancient cities in Mexico, although many people are unaware of it, and it misses the bucket lists of many tourists visiting Mexican archaeological zones.

In February of 1881 Swiss-American archaeologist Adolph Bandelier left Cochití Pueblo in New Mexico for points south. Sponsored by the Archaeological Institute, he was to join the Lorillard Expedition headed by famous French anthropologist Désiré Charnay which was exploring major ruins in central Mexico. When the eager Bandelier arrived in Mexico City, he had found that Charnay had already left for France. Disappointed, Bandelier made the best of it and got the okay from his backers to explore the ancient ruins by himself. He spent 6 months doing so. He started in Cholula and spent months surveying the gigantic pyramid at the site described in Mexico Unexplained episode number 26: https://mexicounexplained.com/cholula-largest-pyramid-world/ From here Bandelier went to Mitla and then to the site of Tlacolula with his final destination being the gigantic pre-Hispanic city of Monte Albán located in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. He would return to the States in March of 1882 and would publish the first account in English about these mysterious ruins in 1884 in an Archaeological Institute paper titled “An Archaeological Tour in Mexico in 1881.” Interest in this site was sporadic in the coming decades with intensive study only beginning in the 1930s by the Mexicans and then resuming in the 1960s by the Americans. Today, Monte Albán is seen as one of the most important ancient cities in Mexico, although many people are unaware of it, and it misses the bucket lists of many tourists visiting Mexican archaeological zones.

The ruins of Monte Albán are located in an elevated mountainous area in the middle of the Valley of Oaxaca where four branches of the valley meet. The site is only about 6 miles west of modern-day Oaxaca City and some of the outlying areas of Monte Albán are now being threatened by encroaching urban sprawl. The main ceremonial center of the city is 6,400 feet above sea level and about 1,300 feet above the valley floor which made it easy to defend against enemy attack. The site was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987. Modern indigenous people of Oaxaca often refer to the site as Danipaguache.

Monte Albán was one of the longest continually occupied sites in Mexico. Archaeologists believe that building began there sometime around 500 BC and the people who occupied it are known to history as the Zapotecs. During the city’s formative years, the powerhouse in the Valley of Oaxaca was a city now known as San José Mogte which was an independent kingdom which ruled a large portion of the valley for almost 1,000 years. It is unknown if the rulers of the much older San José Mogote moved their capital to Monte Albán, or if Monte Albán was a kingdom on the rise and supplanted San José Mogote as the dominant power in the region. There were other smaller kingdoms in and around the Valley of Oaxaca at the time and archaeologists believe, given fortifications  present at the ruins of their capitals, that these kingdoms warred with each other. Within 200 years Monte Albán would come to dominate the region and researchers believe that as many as 5,200 people lived in the city by 300 BC. Much of the population increase came from people migrating to the city from nearby villages and other major Oaxacan urban centers. The result was that by around the year 1 AD Monte Albán became one of the most populated cities in Mesoamerica with a population of well over 17,000 people. By 200 AD the Monte Albán state became so powerful that it began taking over and colonizing territories outside the Valley of Oaxaca and establishing its presence through commerce and diplomacy hundreds of miles away. In the early 1980s archaeologists identified a Zapotec barrio in the central Mexican city of Teotihuacán that dated to the first few centuries AD. This, researchers believe, is evidence of an alliance or a coexistence of mutual benefit existing between these powerful states. Some scholars believe that the noble families of Monte Albán and Teotihuacán were united through a system of marriages across time. Whatever the case may have been, the relations between these two polities were peaceful. The time between 500 AD and 1000 AD is very important for this site and those under the domination of Monte Albán. The city started its slow decline around 500 AD and those cities, villages, and agricultural areas under Monte Albán’s control slowly started to break away and assert their independence. We see a collapse of the older order throughout ancient Mexico at this time, which included the Zapotec ally of Teotihuacán in the central highlands and the entirety of Classic Maya civilization. After 1000 AD Monte Albán was largely abandoned save for a few squatters and those who returned to the site for ritualistic purposes. By the time the first Spaniards arrived in the Valley of Oaxaca in the 1520s, they found the region divided up into several independent kingdoms. The city of Monte Albán was a mysterious empty shell of what it once was with no permanent population, and no one could read the rudimentary inscriptions left on its monuments.

present at the ruins of their capitals, that these kingdoms warred with each other. Within 200 years Monte Albán would come to dominate the region and researchers believe that as many as 5,200 people lived in the city by 300 BC. Much of the population increase came from people migrating to the city from nearby villages and other major Oaxacan urban centers. The result was that by around the year 1 AD Monte Albán became one of the most populated cities in Mesoamerica with a population of well over 17,000 people. By 200 AD the Monte Albán state became so powerful that it began taking over and colonizing territories outside the Valley of Oaxaca and establishing its presence through commerce and diplomacy hundreds of miles away. In the early 1980s archaeologists identified a Zapotec barrio in the central Mexican city of Teotihuacán that dated to the first few centuries AD. This, researchers believe, is evidence of an alliance or a coexistence of mutual benefit existing between these powerful states. Some scholars believe that the noble families of Monte Albán and Teotihuacán were united through a system of marriages across time. Whatever the case may have been, the relations between these two polities were peaceful. The time between 500 AD and 1000 AD is very important for this site and those under the domination of Monte Albán. The city started its slow decline around 500 AD and those cities, villages, and agricultural areas under Monte Albán’s control slowly started to break away and assert their independence. We see a collapse of the older order throughout ancient Mexico at this time, which included the Zapotec ally of Teotihuacán in the central highlands and the entirety of Classic Maya civilization. After 1000 AD Monte Albán was largely abandoned save for a few squatters and those who returned to the site for ritualistic purposes. By the time the first Spaniards arrived in the Valley of Oaxaca in the 1520s, they found the region divided up into several independent kingdoms. The city of Monte Albán was a mysterious empty shell of what it once was with no permanent population, and no one could read the rudimentary inscriptions left on its monuments.

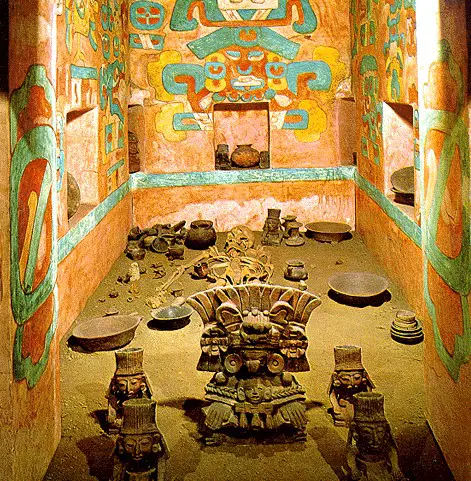

So, what does this city look like today? The site is aligned north-south and the heart of Monte Albán is its civic-ceremonial center dominated by the Central Plaza. This massive public space measures approximately 450 feet across by about 900 feet long. Researchers theorize that the entire population of the city could have fit in the plaza, which was created by leveling off part of the mountain and reinforcing the ground with plaster. At either end of the plaza, we find the North Platform and the South Platform, accessible by large, wide staircases. The larger of the two platforms is the South Platform. This pyramidal structure measures 300 feet across and 45 feet tall. Archaeologists theorize that on top of these platforms there were once temples. On the eastern and western  lanks of the Central Plaza are smaller platforms which also may have had some ritual significance. The buildings on top of these platforms have two rooms. It was Zapotec custom to construct small temples or shrines in this two-room fashion, with the front room serving as a sort of reception area and the back room serving to house sacred relics or other objects of veneration. All these temples had east-west openings, following the trajectory of the sun. Near the midway point on the eastern side of the plaza were elite residences. An expansive structure currently known as “The Palace” most likely housed the ruling family or other Monte Albán elites. The Palace is comprised of a series of maze-like corridors leading to secluded rooms that are difficult to access. North of the elite residences on the east side of the plaza is the largest of the city’s 2 known ballcourts. This ballcourt lacks stone rings and this was typical in the design of Oaxaca-area ballcourts. Instead of rings, two niches were placed in opposite diagonal corners. Researchers can’t agree as to what those niches were used for. Some believe they served as a proxy for the rings and were used in scoring. Others think that they merely served as niches to house figurines of gods or patron spirits who were watching over the game. Just to the northwest of the Central Plaza is the tomb complex, which once housed some of the most elaborate burials in all ancient Mexico. The thousands of artifacts found in these tombs now exist in museums, with most of the items to be found at the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. Of particular interest is Tomb number 7, excavated under the supervision of the “First Lady of Mexican Archaeology” Eulalia Guzmán in 1933. The tomb once held the remains and artifacts belonging to a prominent Monte Albán noble family but was also repurposed by the Mixtecs who used Tomb 7 as a burial for one of their elite families centuries later. While some of the structures around the site’s main plaza were reserved for members of the ruling families of Monte Albán, most of the population of the city lived on the slopes of the mountain on which the site was situated. The homes of the non-elites were not constructed of stone but of adobe, and the people who lived there mostly worked the fields in the valleys below.

lanks of the Central Plaza are smaller platforms which also may have had some ritual significance. The buildings on top of these platforms have two rooms. It was Zapotec custom to construct small temples or shrines in this two-room fashion, with the front room serving as a sort of reception area and the back room serving to house sacred relics or other objects of veneration. All these temples had east-west openings, following the trajectory of the sun. Near the midway point on the eastern side of the plaza were elite residences. An expansive structure currently known as “The Palace” most likely housed the ruling family or other Monte Albán elites. The Palace is comprised of a series of maze-like corridors leading to secluded rooms that are difficult to access. North of the elite residences on the east side of the plaza is the largest of the city’s 2 known ballcourts. This ballcourt lacks stone rings and this was typical in the design of Oaxaca-area ballcourts. Instead of rings, two niches were placed in opposite diagonal corners. Researchers can’t agree as to what those niches were used for. Some believe they served as a proxy for the rings and were used in scoring. Others think that they merely served as niches to house figurines of gods or patron spirits who were watching over the game. Just to the northwest of the Central Plaza is the tomb complex, which once housed some of the most elaborate burials in all ancient Mexico. The thousands of artifacts found in these tombs now exist in museums, with most of the items to be found at the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. Of particular interest is Tomb number 7, excavated under the supervision of the “First Lady of Mexican Archaeology” Eulalia Guzmán in 1933. The tomb once held the remains and artifacts belonging to a prominent Monte Albán noble family but was also repurposed by the Mixtecs who used Tomb 7 as a burial for one of their elite families centuries later. While some of the structures around the site’s main plaza were reserved for members of the ruling families of Monte Albán, most of the population of the city lived on the slopes of the mountain on which the site was situated. The homes of the non-elites were not constructed of stone but of adobe, and the people who lived there mostly worked the fields in the valleys below.

Monte Albán is known for its public art with hundreds of stone carvings cataloged. Of special note are the so-called “danzante” or “dancer” carvings which number about 300. The danzantes feature men in contorted positions with the designation “dancer” given to them by 19th Century archaeologists. Recent scholarship suggests that these illustrations may depict sacrificial victims or captives. Art historians who specialize in ancient Mexico are quick to point out a strong Olmec influence in this danzante art. Could these depict ancestors? Were they rulers of defeated and subjugated  kingdoms? These unique works of art are open to interpretation. The carvings on Building J are also worth mentioning. The building sits in the middle of the Central Plaza and seems out of place because of its distinctive arrow shape. 40 carved blocks make up the building, and according to Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso, these are “conquest slabs” celebrating victories in battle over competing kingdoms in the region. The carved slabs date from 100 BC to 200 AD which was during Monte Albán’s period of intensive military expansion. The slabs are carved with some elements of the Zapotec writing system and also include upside-down heads which may indicate subjugation. Also worth mentioning are the 4 stelae – the carved monoliths found throughout ancient Mexico – located in each of the four corners of the South Platform. The stelae depict two figures and hieroglyphs, and their messages seem to be the same. The identical scenes show a Teotihuacán ambassador leaving his home in Teotihuacán and traveling to Monte Albán where he is greeted by local elites. Archaeologists theorize that Teotihuacán ambassadors, or perhaps members of the faraway city’s royal family, were present at Monte Albán for the dedication of the South Platform. In any case, the stelae seem to solidify the theory that Monte Albán had excellent relations with its sister superpower in central Mexico.

kingdoms? These unique works of art are open to interpretation. The carvings on Building J are also worth mentioning. The building sits in the middle of the Central Plaza and seems out of place because of its distinctive arrow shape. 40 carved blocks make up the building, and according to Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso, these are “conquest slabs” celebrating victories in battle over competing kingdoms in the region. The carved slabs date from 100 BC to 200 AD which was during Monte Albán’s period of intensive military expansion. The slabs are carved with some elements of the Zapotec writing system and also include upside-down heads which may indicate subjugation. Also worth mentioning are the 4 stelae – the carved monoliths found throughout ancient Mexico – located in each of the four corners of the South Platform. The stelae depict two figures and hieroglyphs, and their messages seem to be the same. The identical scenes show a Teotihuacán ambassador leaving his home in Teotihuacán and traveling to Monte Albán where he is greeted by local elites. Archaeologists theorize that Teotihuacán ambassadors, or perhaps members of the faraway city’s royal family, were present at Monte Albán for the dedication of the South Platform. In any case, the stelae seem to solidify the theory that Monte Albán had excellent relations with its sister superpower in central Mexico.

In colonial days the biggest threat to Monte Albán was the removal of stones by people seeking easy access to building materials. Today, urban sprawl from Oaxaca City is a distinct threat, posing danger to undisturbed ruins found on the outskirts of Monte Albán. It seems like a race against the clock to preserve new finds from modern construction, and this is an important race as there is still so much more to learn about this intriguing and important ancient civilization.

REFERENCES

Porter Weaver, Muriel. The Aztecs, the Maya and their Predecessors. New York: Seminar Press, 1972. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3AqGkgt