Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hernán Cortés and his band of Spanish conquistadors finally made it to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán as honored guests of the great tlatoani of the Aztecs, Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, better known to history as Emperor Montezuma. The date was November 8, 1519. The Europeans marveled at the city in the middle of the lake connected to the mainland by a series of causeways. Some Spaniards accompanying Cortés had been to many of the magnificent cities of the Old World – Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem – and had never seen a place quite like Tenochtitlán. When the Spaniards entered the city, they were greeted by Montezuma in an elaborate display, as noted in the writings of one of the soldiers present, Bernal Díaz del Castillo. In his work published years later, he described the scene after they crossed the causeway:

Hernán Cortés and his band of Spanish conquistadors finally made it to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán as honored guests of the great tlatoani of the Aztecs, Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, better known to history as Emperor Montezuma. The date was November 8, 1519. The Europeans marveled at the city in the middle of the lake connected to the mainland by a series of causeways. Some Spaniards accompanying Cortés had been to many of the magnificent cities of the Old World – Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem – and had never seen a place quite like Tenochtitlán. When the Spaniards entered the city, they were greeted by Montezuma in an elaborate display, as noted in the writings of one of the soldiers present, Bernal Díaz del Castillo. In his work published years later, he described the scene after they crossed the causeway:

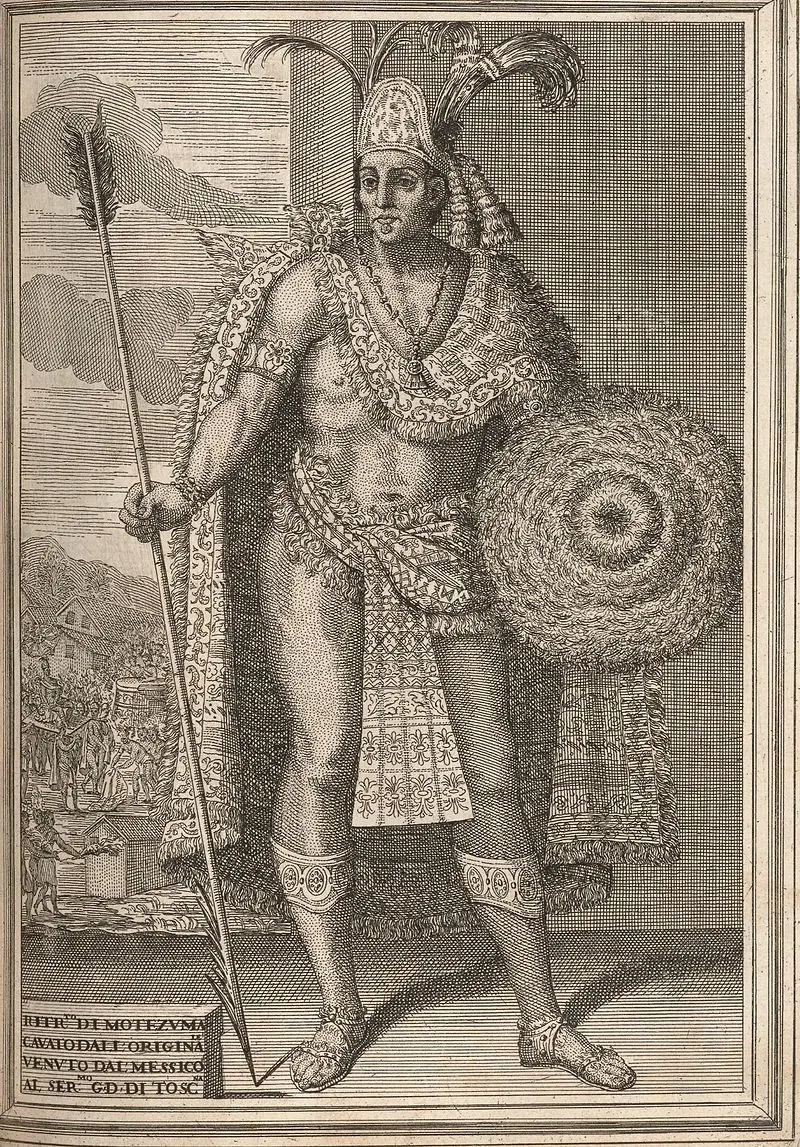

“There we halted for a good while, and Cacamatzin, the Lord of Texcoco, and the Lord of Iztapalapa and the Lord of Tacuba and the Lord of Coyoacan went on in advance to meet the great Montezuma, who was approaching in a rich litter accompanied by other great lords and caciques, who owned vassals. When we arrived near to Tenochtitlán, where there were some other small towers, the great Montezuma got down from his litter, and those great caciques supported him with their arms beneath a marvelously rich canopy of green-colored feathers with much gold and silver embroidery and with pearls and emeralds suspended from a sort of bordering, which was wonderful to look at. The great Montezuma was richly attired according to his usage, and he was shod with sandals, the soles were of gold and the upper part adorned with precious stones. The four chieftains who supported his arms were also richly clothed according to their usage, in garments which were apparently held ready for them on the road to enable them to accompany their prince, for they did not appear in such attire when they came to receive us. Besides these four chieftains, there were four other great caciques who supported the canopy over their heads, and many other lords who walked before the great Montezuma, sweeping the ground where he would tread and spreading cloths on it, so that he should not tread on the earth. Not one of these chieftains dared even to think of looking him in the face, but kept their eyes lowered with great reverence, except those four relations, his nephews, who supported him with their arms.”

So went the first formal encounter between two civilizations, the Aztec and the Spanish, inarguably one of the most important events in human history. Within a few years one of these civilizations would be completely destroyed and before that, its great leader would die at the hands of his own people.

In the language of the Aztecs, Nahuatl, Montezuma’s formal name, has two parts, “Motecuhzoma” and “Xocoyotzin”. “Motecuhzoma” means, “He who is angry in a noble way.” Xocoyotzin, means, “Honored young one.” In most histories he is known as Montezuma the Second. Even though the Aztecs did not number their rulers the way Europeans did, there was another Montezuma who ruled the Aztec empire before the one who encountered the Spanish. Motecuhuzoma Ilhuicamina, literally, “The older one who is angry in a noble way,” ruled over the Aztecs from 1440 to 1469, and is known in histories as Montezuma the First. In the royal line of Tenochtitlán, Montezuma the First was succeeded in 1469 by his cousin Emperor Axayacatl who would later father a child to inherit his realm, later known as Montezuma the Second. When scholars usually use the name “Montezuma,” they are referring to the emperor who met with Cortés and oversaw the clash of civilizations. In Aztec writings, Montezuma was often written in a glyph depicting a small crown called a xiuhuitzolli draped with hair braids and an earspool next to a speech scroll. The speech scroll in Montezuma’s name glyph was important because one of the emperor’s titles was tlatoani, or literally “speaker,” because he spoke for his people and spoke directly to the gods. Often times tlatoani was used to signify “ruler” or “king” in everyday Nahuatl speech, but it became used as a formal title for the Aztec emperor.

In the language of the Aztecs, Nahuatl, Montezuma’s formal name, has two parts, “Motecuhzoma” and “Xocoyotzin”. “Motecuhzoma” means, “He who is angry in a noble way.” Xocoyotzin, means, “Honored young one.” In most histories he is known as Montezuma the Second. Even though the Aztecs did not number their rulers the way Europeans did, there was another Montezuma who ruled the Aztec empire before the one who encountered the Spanish. Motecuhuzoma Ilhuicamina, literally, “The older one who is angry in a noble way,” ruled over the Aztecs from 1440 to 1469, and is known in histories as Montezuma the First. In the royal line of Tenochtitlán, Montezuma the First was succeeded in 1469 by his cousin Emperor Axayacatl who would later father a child to inherit his realm, later known as Montezuma the Second. When scholars usually use the name “Montezuma,” they are referring to the emperor who met with Cortés and oversaw the clash of civilizations. In Aztec writings, Montezuma was often written in a glyph depicting a small crown called a xiuhuitzolli draped with hair braids and an earspool next to a speech scroll. The speech scroll in Montezuma’s name glyph was important because one of the emperor’s titles was tlatoani, or literally “speaker,” because he spoke for his people and spoke directly to the gods. Often times tlatoani was used to signify “ruler” or “king” in everyday Nahuatl speech, but it became used as a formal title for the Aztec emperor.

The future ruler of the Aztecs was born in the imperial palace at Tenochtitlán in 1466. When he was three years old his father Axayacatl became emperor of the Aztecs. From an early age, Montezuma was groomed to rule the empire and as a young teenager he accompanied his uncles – Tizoc and Ahuizotl – on military campaigns giving him valuable experience in the field. One of the campaigns in which the young Montezuma proved his leadership ability was during the conquest of Xoconochco, under the command of his uncle Emperor Ahuizotl. Xoconochco was a valuable region for the empire to secure and often difficult to govern as it was 550 miles from the Aztec capital. For more on Xoconocho, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 162. https://mexicounexplained.com//xoconochco-the-remotest-aztec-province/ Montezuma’s uncle and predecessor, Emperor Ahuizotl, expanded the Aztec Empire to the greatest extent it had ever been. This gave the future Emperor Montezuma a great deal of experience not only in military matters, but the campaigns made the young noble familiar with the various lands and peoples of his future realm. Whether fighting the Zapotecs or the Chichimecs, or traveling overland to meet the enemy in an unfamiliar territory, the young Montezuma got to know the deserts, dense jungles, high mountains and sandy coastal beaches of a land that one day would be his to rule. By 1502, upon the death of his uncle, the Emperor Ahuizotl, Montezuma was more than ready to take charge of this vast empire.

At the time of the Spanish contact, Bernal Díaz describe Montezuma thus:

“He was of good height and well proportioned, slender and spare of flesh, not very swarthy. With the self-command of a prince, he could seem cheerful as well as grave and severe when necessary.”

The 33-year-old Emperor Montezuma took his role seriously and one of his first moves as ruler of the Aztec Empire was to get rid of merit-based promotions in the military and in government service throughout the Aztec world. Nobles alone could serve in high positions, with close blood relatives given special consideration. Montezuma dismissed all military and bureaucratic appointees hand-picked by his uncle and predecessor Emperor Ahuizotl. Even though these people were deemed highly competent and promoted to their positions by ability, Montezuma was more interested in securing the loyalty of those serving in the highest ranks through family connections. The young Montezuma continued the far-reaching military campaigns of his uncle but ruled his subjects in a different way. While Emperor Ahuizotl was considered more affectionate and warmhearted to his people, Montezuma was colder and more distant. He ruled his vassals in a way that would be considered more oppressive and domineering. This new style of rule did not make him loved among the millions he subjugated, and his leadership style caused great discontent throughout the empire. While his uncle was more hands-on and involved in all aspects of matters of state, Montezuma spent a great deal of time meditating, communing with the gods and engaging in solitary pursuits. Under his rule, he expanded the imperial palace and with it came a more elaborate and luxurious life at court. The Spanish marveled at the sumptuous banquets and lavish entertainment at the Aztec court. The emperor personally tended to the beautiful palace gardens and oversaw one of the largest private zoos in the history of the world. For more information about Montezuma’s Zoo, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 43. https://mexicounexplained.com//montezumas-zoo/

The 33-year-old Emperor Montezuma took his role seriously and one of his first moves as ruler of the Aztec Empire was to get rid of merit-based promotions in the military and in government service throughout the Aztec world. Nobles alone could serve in high positions, with close blood relatives given special consideration. Montezuma dismissed all military and bureaucratic appointees hand-picked by his uncle and predecessor Emperor Ahuizotl. Even though these people were deemed highly competent and promoted to their positions by ability, Montezuma was more interested in securing the loyalty of those serving in the highest ranks through family connections. The young Montezuma continued the far-reaching military campaigns of his uncle but ruled his subjects in a different way. While Emperor Ahuizotl was considered more affectionate and warmhearted to his people, Montezuma was colder and more distant. He ruled his vassals in a way that would be considered more oppressive and domineering. This new style of rule did not make him loved among the millions he subjugated, and his leadership style caused great discontent throughout the empire. While his uncle was more hands-on and involved in all aspects of matters of state, Montezuma spent a great deal of time meditating, communing with the gods and engaging in solitary pursuits. Under his rule, he expanded the imperial palace and with it came a more elaborate and luxurious life at court. The Spanish marveled at the sumptuous banquets and lavish entertainment at the Aztec court. The emperor personally tended to the beautiful palace gardens and oversaw one of the largest private zoos in the history of the world. For more information about Montezuma’s Zoo, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 43. https://mexicounexplained.com//montezumas-zoo/

Fifteen years into his reign, in 1517, Montezuma received strange reports of floating temples seen off the coast in the kingdom of the Totonacs, a people the Aztecs conquered in the mid-1400s. The temples came ashore and strange pale-colored men with hairy faces set foot on the land. Some of the men were made of metal and rode gigantic deer. The messengers arriving at the imperial palace at Tenochtitlán with the news of the visitors were describing the Juan de Grijalva Expedition which had set off from Cuba, landed in the Yucatán and skirted the Gulf Coast, exploring the shores of the modern Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. Hernán Cortés would stay at Grijalva’s house in Trinidad, Cuba the following year where he would learn about the large landmass to the west. By the time Cortés had arrived on Mexican shores, Montezuma had been mentally prepared for this new potential threat and while the Spaniard plotted his march to the interior the Aztec emperor formulated a plan. Montezuma wanted to size up the newcomers, so he sent emissaries bearing gifts along with a warm invitation to come to Tenochtitlán as honored guests.

In popular histories of the Spanish arrival in Mexico, some sources claim that Montezuma thought Cortés was the returning god Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent found throughout ancient Mesoamerica. This is the reason why the emperor welcomed the conquistador to his capital, so the story goes. Recent scholarship suggests that this story was inserted into Mexican history a few generations after the Conquest to give some sort of legitimacy to the initial Spanish interactions with the Aztec Empire. The Aztecs thinking the Europeans as gods sent a powerful message about status and power to those conquered Indians living in subsequent generations. With the Grijalva Expedition and reports of other Europeans shipwrecked on Mexican shores before the arrival of Cortés, Europeans were not new to the Aztecs when Cortés showed up. The Aztecs knew that this was no god. For more information about the Cortés-Quetzalcoatl connection, please see Mexico Unexplained episode 100. https://mexicounexplained.com//quetzalcoatl-man-myth-god/

Historians debate whether Montezuma knew the real intentions of the Spanish from the start, but the Aztec ruler played it cool and got to know the visitors in the few months they were allowed to stay in the capital. When Cortés’ intentions became clearer, Montezuma tried to buy him off to get him to leave, but that was not enough for the conquistador who wanted the whole Aztec Empire for the Spanish king. Historians are unsure when Montezuma became under a sort of house arrest in his own palace and subject to Spanish authority. Some believe that this took place when Cortés left the Aztec capital to fight Pánfilo de Narváez, a man sent by Spanish authorities to arrest him. When Cortés was away from Tenochtitlán the situation between his soldiers and the Aztecs in the capital became tense. In May 1520, the Spanish soldiers massacred a group of elites engaged in ceremonies in the Great Temple and with the city in revolt against the foreigners because of that, the conquistadors took Montezuma hostage to ensure their own safety. This hostage situation shook the empire to its core. Many Aztec subjects, from the highest ranks of the nobility to the everyday commoners, blamed Montezuma for inviting the Europeans into their city as guests. They saw him as a weak an ineffective ruler. When Cortés returned to the capital, he found Tenochtitlán in a state of anarchy. The old social order had been upended and turmoil existed throughout the very heart of the empire. Dissatisfied with their leader, when Montezuma tried to address an angry mob in the center of the city, his own people turned on him and stoned him to death. The Spanish immediately selected a new emperor in name only from Montezuma’s family, Cuahutémoc, but he served as a puppet and had no real power. A few years later the Spanish ended the farce and there were no more tlatoanis to rule over one of the most expansive and diverse empires of the ancient world. Montezuma was truly the last real ruler of the Aztecs.

Historians debate whether Montezuma knew the real intentions of the Spanish from the start, but the Aztec ruler played it cool and got to know the visitors in the few months they were allowed to stay in the capital. When Cortés’ intentions became clearer, Montezuma tried to buy him off to get him to leave, but that was not enough for the conquistador who wanted the whole Aztec Empire for the Spanish king. Historians are unsure when Montezuma became under a sort of house arrest in his own palace and subject to Spanish authority. Some believe that this took place when Cortés left the Aztec capital to fight Pánfilo de Narváez, a man sent by Spanish authorities to arrest him. When Cortés was away from Tenochtitlán the situation between his soldiers and the Aztecs in the capital became tense. In May 1520, the Spanish soldiers massacred a group of elites engaged in ceremonies in the Great Temple and with the city in revolt against the foreigners because of that, the conquistadors took Montezuma hostage to ensure their own safety. This hostage situation shook the empire to its core. Many Aztec subjects, from the highest ranks of the nobility to the everyday commoners, blamed Montezuma for inviting the Europeans into their city as guests. They saw him as a weak an ineffective ruler. When Cortés returned to the capital, he found Tenochtitlán in a state of anarchy. The old social order had been upended and turmoil existed throughout the very heart of the empire. Dissatisfied with their leader, when Montezuma tried to address an angry mob in the center of the city, his own people turned on him and stoned him to death. The Spanish immediately selected a new emperor in name only from Montezuma’s family, Cuahutémoc, but he served as a puppet and had no real power. A few years later the Spanish ended the farce and there were no more tlatoanis to rule over one of the most expansive and diverse empires of the ancient world. Montezuma was truly the last real ruler of the Aztecs.

REFERENCES:

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1972. We are an Amazon Affiliate. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2Wf5wTg

Stuart, Gene S. The Might Aztecs. Washington, DC: The National Geographic Society, 1981. We are an Amazon Affiliate. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/32c24ws