Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The young King Sisibotari knew he had to face the inevitable one day, and as one of the leaders of the Opata people he wanted to be the one to decide when to face the inevitable. The year was 1619 and the place was northwestern Mexico in the modern-day state of Sonora. Sisibotari had heard stories of the black-robed, pale-faced foreigners for years from his father and grandfather. The king had even seen a few of them from afar on his travels to neighboring lands. The presence of these foreigners had increased over the years and some of the tribes close to the Opata – both friends and foes – had made deals with these intruders and even let them establish themselves in their territories. The day had come when the young Opata king wished to meet with the foreigners face to face to get a sense of their intentions and to figure out a way to peacefully coexist with him. The historic meeting happened in Yaqui territory. At that time, most of the Yaquis had already converted to Christianity and had accepted many of the Spanish ways. King Sisibotari and a small entourage of Opata village leaders met with the middle-aged Spanish-born Jesuit Andrés Pérez de Ribas and a Spanish military captain. The meeting was friendly, and the Spanish and Opatans discussed many things. Later in his diaries, the Jesuit priest would describe King Sisibotari. Father Pérez de Ribas wrote:

The young King Sisibotari knew he had to face the inevitable one day, and as one of the leaders of the Opata people he wanted to be the one to decide when to face the inevitable. The year was 1619 and the place was northwestern Mexico in the modern-day state of Sonora. Sisibotari had heard stories of the black-robed, pale-faced foreigners for years from his father and grandfather. The king had even seen a few of them from afar on his travels to neighboring lands. The presence of these foreigners had increased over the years and some of the tribes close to the Opata – both friends and foes – had made deals with these intruders and even let them establish themselves in their territories. The day had come when the young Opata king wished to meet with the foreigners face to face to get a sense of their intentions and to figure out a way to peacefully coexist with him. The historic meeting happened in Yaqui territory. At that time, most of the Yaquis had already converted to Christianity and had accepted many of the Spanish ways. King Sisibotari and a small entourage of Opata village leaders met with the middle-aged Spanish-born Jesuit Andrés Pérez de Ribas and a Spanish military captain. The meeting was friendly, and the Spanish and Opatans discussed many things. Later in his diaries, the Jesuit priest would describe King Sisibotari. Father Pérez de Ribas wrote:

“He was handsome and still young. The king wore a long coat attached at his shoulder like a cape, and his loins were covered with a cloth, as was the custom of that nation. On the wrist of his left hand, which holds the bow when the hand pulls the cord to send the arrow, he wore a very becoming marten skin.”

At the end of the meeting, King Sisibotari invited the Jesuits to come into his territory. Was the king partly persuaded by the material enrichment of his neighbors by the Spanish? Did he just want an alliance with a stronger power? Did he see the eventual takeover of his lands and wanted a peaceful co-existence from the start? History is unclear as to the Opata king’s motives. The priest and that captain were not prepared for the invitation and did not cross the eastern mountains to visit Sisibotari’s kingdom at that time. They, instead, returned to their mission in Sinaloa. King Sisibotari was not satisfied and felt like the Spanish had left him hanging. In the following year, the king and a small group representing other Opatan kingdoms made the long journey to visit Father Andrés at his mission in Sinaloa. The day Sisbotari arrived, a young priest serving at the Sinaloa mission described the Opatan ruler as, “Handsome. Knightly in bearing and courtly in

At the end of the meeting, King Sisibotari invited the Jesuits to come into his territory. Was the king partly persuaded by the material enrichment of his neighbors by the Spanish? Did he just want an alliance with a stronger power? Did he see the eventual takeover of his lands and wanted a peaceful co-existence from the start? History is unclear as to the Opata king’s motives. The priest and that captain were not prepared for the invitation and did not cross the eastern mountains to visit Sisibotari’s kingdom at that time. They, instead, returned to their mission in Sinaloa. King Sisibotari was not satisfied and felt like the Spanish had left him hanging. In the following year, the king and a small group representing other Opatan kingdoms made the long journey to visit Father Andrés at his mission in Sinaloa. The day Sisbotari arrived, a young priest serving at the Sinaloa mission described the Opatan ruler as, “Handsome. Knightly in bearing and courtly in  manner.” As a gift for the Jesuit Superior the king brought with him a gigantic golden eagle used in hunting. As a further gesture of peace and good faith, he also gave the Jesuits 11 young men to instruct in the ways of the Spanish and to convert to Christianity. The king wanted to do what he could to hasten the Spanish alliance with his people and to hurry along the inevitable at his pace and hopefully under his terms. While in Sinaloa the king earned the nickname “Gran Sisibotari,” or “The Great Sisibotari.” The Spanish promised to send missionaries and the Opatan delegation returned north to their homeland. When the Spanish still didn’t follow through on their promises, King Sisibotari returned to the Sinaloa mission the following year, 1621. Perhaps never before in the colonial history of Mexico had an indigenous ruler so begged for Spanish involvement. A few months after the second visit, in the fall of 1621, the Spanish finally sent a contingent to the town of Saguaripa, the chief settlement among the 70 towns and villages in Sisibotari’s kingdom. This was partly to fulfill the promise to the Opata king and partly to ask for help. The harvest throughout Sinaloa was bad in 1621 and the Jesuit padres felt the region was on a verge of a famine. King Sisibotari saw this as an opportunity to ingratiate himself with the Spanish. The Spanish came with pack animals, so the king had his people load up the animals with food, which was plentiful in the Sisibotari’s realm. After the food arrived at the mission in Sinaloa, the Spanish sent more missionaries and other resources they promised. Over the next 5 or 6 years the majority of the Great Sisbotari’s kingdom had converted to Christianity. The king and the elites continued to enjoy high status and a higher quality of life under Spanish rule, as well as Spanish protection against their enemies. The great king would die some 30 years later during an epidemic that swept across his realm.

manner.” As a gift for the Jesuit Superior the king brought with him a gigantic golden eagle used in hunting. As a further gesture of peace and good faith, he also gave the Jesuits 11 young men to instruct in the ways of the Spanish and to convert to Christianity. The king wanted to do what he could to hasten the Spanish alliance with his people and to hurry along the inevitable at his pace and hopefully under his terms. While in Sinaloa the king earned the nickname “Gran Sisibotari,” or “The Great Sisibotari.” The Spanish promised to send missionaries and the Opatan delegation returned north to their homeland. When the Spanish still didn’t follow through on their promises, King Sisibotari returned to the Sinaloa mission the following year, 1621. Perhaps never before in the colonial history of Mexico had an indigenous ruler so begged for Spanish involvement. A few months after the second visit, in the fall of 1621, the Spanish finally sent a contingent to the town of Saguaripa, the chief settlement among the 70 towns and villages in Sisibotari’s kingdom. This was partly to fulfill the promise to the Opata king and partly to ask for help. The harvest throughout Sinaloa was bad in 1621 and the Jesuit padres felt the region was on a verge of a famine. King Sisibotari saw this as an opportunity to ingratiate himself with the Spanish. The Spanish came with pack animals, so the king had his people load up the animals with food, which was plentiful in the Sisibotari’s realm. After the food arrived at the mission in Sinaloa, the Spanish sent more missionaries and other resources they promised. Over the next 5 or 6 years the majority of the Great Sisbotari’s kingdom had converted to Christianity. The king and the elites continued to enjoy high status and a higher quality of life under Spanish rule, as well as Spanish protection against their enemies. The great king would die some 30 years later during an epidemic that swept across his realm.

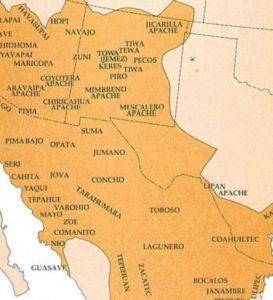

The word “Opata” has conflicting origins. Some researchers believe that the word comes from an extinct Pima dialect and means “enemy.” Others believe that the word comes from an extinct dialect of the Opata people themselves and means, “The iron people.” At the time of Spanish contact, the Opata were mining iron ore and tipping their spears with it, hence this possible name. Anthropologists and historians believe that the Opata started settling the river valleys of the deserts of modern-day Sonora and parts of the modern-day states of Arizona and New Mexico around 1300 AD. A complex civilization developed centered around irrigated agriculture. Communities of Opata were organized into small kingdoms with hereditary rulers which some political scientists would call “statelets” across a wide geographical area. Political units usually centered around a main town or an informal capital city which served as the home of the elites and as a center for trade. There were between 5 and 9 distinct Opata kingdoms which lived in peace with each other and sometimes would band together to fight a common enemy, such as raiding bands of Apaches coming at them from the northeast. The Opata had hot and cold relations with the other indigenous groups surrounding them. Their neighbors to the north were the O’odham, often called the Pima Alto by the Spanish. To the west of Opata territory lived the Seri and the Yaqui or Yoeme, also called the Pima Bajo by the Spanish. To the south and southeast of the Opata kingdoms lived the Tarahumara. Each small kingdom had an elite class and a large slave class. There was also a professional class of craftspeople to produce finished goods for local consumption or trade. As Opata culture emphasized farming, people grew corn, squash, beans and cotton. This was often supplemented with hunting and gathering. The Opata spoke a Uto-Aztecan language divided into three dialects, the Dohema, the Tehuima and the Jova. The Opata language group is closely related to the language of the O’odham of Arizona and those of the Yaqui and Tarahumara peoples.

The Spanish first heard of the Opata through the Cabeza de Vaca expedition that skirted their territory in the early 1530s. The first European contact with an Opatan village was in 1533 by members of the Diego de Guzmán expedition. They called the small Opatan town on the fringes of Yaqui territory, “Pueblo de Corazones,” or in English, “Town of Hearts.” This was a reference to the public cooking of deer hearts that the Spanish witnessed while there. In Spanish maps of northwestern Mexico starting in the 1540s, the vast blank territory inhabited by the Opatan kingdoms was generically called Opatería, or “the land of the Opata.” The next Spanish incursion into Opatería was in the early 1560s when the Francisco Ibarra expedition came through the territory. The Opata kings united their people against the Spanish and resisted Ibarra and his men, eventually driving them away. The Spanish had very little interest in Opatería until the time of the Great King Sisibotari, some 60 years later. Because of contact with the Spanish in the early 1500s, by the time of Sisibotari’s rule, the Opata population across the various kingdoms had declined dramatically due to European-introduced diseases. So, when they saw the handwriting on the wall, Sisibotari and the other rulers of Opatería knew they could not mount a resistance to the Spanish as their ancestors had 60 years prior. The world was changing, and the king and others just wanted a smooth and peaceful transition into whatever Spanish domination would bring them.

The Spanish first heard of the Opata through the Cabeza de Vaca expedition that skirted their territory in the early 1530s. The first European contact with an Opatan village was in 1533 by members of the Diego de Guzmán expedition. They called the small Opatan town on the fringes of Yaqui territory, “Pueblo de Corazones,” or in English, “Town of Hearts.” This was a reference to the public cooking of deer hearts that the Spanish witnessed while there. In Spanish maps of northwestern Mexico starting in the 1540s, the vast blank territory inhabited by the Opatan kingdoms was generically called Opatería, or “the land of the Opata.” The next Spanish incursion into Opatería was in the early 1560s when the Francisco Ibarra expedition came through the territory. The Opata kings united their people against the Spanish and resisted Ibarra and his men, eventually driving them away. The Spanish had very little interest in Opatería until the time of the Great King Sisibotari, some 60 years later. Because of contact with the Spanish in the early 1500s, by the time of Sisibotari’s rule, the Opata population across the various kingdoms had declined dramatically due to European-introduced diseases. So, when they saw the handwriting on the wall, Sisibotari and the other rulers of Opatería knew they could not mount a resistance to the Spanish as their ancestors had 60 years prior. The world was changing, and the king and others just wanted a smooth and peaceful transition into whatever Spanish domination would bring them.

What became of the Opata people after King Sisibotari’s invitation to the Spanish? As previously mentioned, the Spanish started by sending missionaries. By 1650 most of the Opata had converted to Christianity. Between 1650 and 1675 the Jesuits dismantled many of the Opatan towns and villages and created rancherías within the mission system. By 1700 most people in the former Opaería were speaking Spanish and had fully assimilated into European colonial culture. It was during the 1700s that many Opata people migrated out of the homeland, some heading south to work in the mines while some headed north to what is now the American Southwest. In fact, in 1692 a group of Opata accompanied Padre Kino to help found the mission of San Xavier del Bac, which still stands today about 10 miles south of downtown Tucson, Arizona. By 1700 the total population of Opata people was around 20,000, down from the hundreds of thousands that lived in the Opata kingdoms before the Spanish arrived. Throughout the 1700s Spanish settlement increased in Opata territory and sometimes, although infrequently, the settlers clashed with the natives. For the most part, though, the Opata people assimilated well into Spanish colonial society and offered little resistance. Despite the appearance of contentment, perhaps there were some unseen things brewing? An important piece of trivia pops up when investigating these seemingly cooperative and peaceful people. In the year 1820, just months before Spain granted Mexico its independence, 300 Opata warriors rose up and defeated a Spanish force of 1,000 soldiers, destroying the mining town of Tonichi. This Opata uprising, a mere footnote to history, may very well be the last military defeat of the Spanish Empire’s troops in the New World by an indigenous group. The Spanish went back to Opatería with 2,000 troops and put down the Opatan rebellion, executing many of the leaders and exiling others. Weeks later, the troops evacuated Opata territory when Mexico gained its independence from Spain.

The Opatan grievances that had built up throughout the 1700s and culminated in the revolts of 1820 did not end with the creation of the new country of Mexico. The new powers in Mexico City wanted greater central authority and treated the indigenous people of Sonora miserably. By the 1860s when France briefly occupied Mexico, the Opata people sided with the French. In fact, an Opata, Refugio Tanori, became a noted general in the Mexican army under the rule of Emperor Maximilian. Because of their support for the French, after the end of Maximilian’s rule the Mexican republican forces exacted revenge on the Opata. What was left of their traditional lands was taken away. The remaining Opata resistance to Mexican rule was snuffed out and dealt with harshly. By 1900 there were only about 500 or so full-blood Opatas left. Anthropologists visiting Sonora in the early 20th Century noted that most people who were descended from the Opata were indistinguishable from the larger Mexican mestizo society. Very little of the Opata culture and lifeways survived into the last century. Although some isolated words exist to this day in Mexican Sonoran vocabularies, the Opata language and its dialects have been dead since about the 1940s. Various linguistic texts exist from the early 1900s when anthropologists and language scholars desperately tried to understand and document the dying Opata dialects. These texts are now being used by people claiming Opata descent in Sonora and California in an attempt to revive the Opata language, but they are having very little success, mainly due to a lack of interest and an absence of any sort of intact tribal community. The DNA of the Opata may live on, but their complex culture is completely gone.

The Opatan grievances that had built up throughout the 1700s and culminated in the revolts of 1820 did not end with the creation of the new country of Mexico. The new powers in Mexico City wanted greater central authority and treated the indigenous people of Sonora miserably. By the 1860s when France briefly occupied Mexico, the Opata people sided with the French. In fact, an Opata, Refugio Tanori, became a noted general in the Mexican army under the rule of Emperor Maximilian. Because of their support for the French, after the end of Maximilian’s rule the Mexican republican forces exacted revenge on the Opata. What was left of their traditional lands was taken away. The remaining Opata resistance to Mexican rule was snuffed out and dealt with harshly. By 1900 there were only about 500 or so full-blood Opatas left. Anthropologists visiting Sonora in the early 20th Century noted that most people who were descended from the Opata were indistinguishable from the larger Mexican mestizo society. Very little of the Opata culture and lifeways survived into the last century. Although some isolated words exist to this day in Mexican Sonoran vocabularies, the Opata language and its dialects have been dead since about the 1940s. Various linguistic texts exist from the early 1900s when anthropologists and language scholars desperately tried to understand and document the dying Opata dialects. These texts are now being used by people claiming Opata descent in Sonora and California in an attempt to revive the Opata language, but they are having very little success, mainly due to a lack of interest and an absence of any sort of intact tribal community. The DNA of the Opata may live on, but their complex culture is completely gone.

REFERENCES

Basauri, Carlos. “Los Opatas.” In La población indìgena de México. Mexico City: Secretaria de Educación Pública, 1940. (in Spanish)

Dunne, Peter Masten. Pioneer Jesuits in Northern Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1944. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2JqXgcA

Hinton, Thomas B. “Remnant Tribes in Sonora: Opata, Pima, Papago, and Seri.” In Handbook of Middle American Indians, edited by Robert Wauchope. Vol. 8, Ethnology, Part Two, edited by Evon Z. Vogt, 879-888. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1969.

Johnson, Jean Bassett. The Opata: An Inland Tribe of Sonora. University of New Mexico Publications in Anthropology, no.6. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1950.