Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

“I was born where solar rays

stared down at me from overhead

not squint-eyed as in other climes.”

So wrote the nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz about her humble birth, in the small town of San Miguel Nepantla, in the fertile foothills of the Mexican volcano Popocatépetl. The person who would later become one of the most renown and controversial women in colonial Mexico was born on November 12, 1648 in this sunny place between Cuernavaca and Puebla in central New Spain. While lost to history for the better part of two hundred years, it was only in the 20th century that scholars and biographers began examining the life and times of this fascinating historical figure. One of the giants of Spanish literature of her time, and read from Spain to India to the Philippines, many people do not know much about this woman other than wondering casually who is behind the face on the Mexican 200-peso note.

So wrote the nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz about her humble birth, in the small town of San Miguel Nepantla, in the fertile foothills of the Mexican volcano Popocatépetl. The person who would later become one of the most renown and controversial women in colonial Mexico was born on November 12, 1648 in this sunny place between Cuernavaca and Puebla in central New Spain. While lost to history for the better part of two hundred years, it was only in the 20th century that scholars and biographers began examining the life and times of this fascinating historical figure. One of the giants of Spanish literature of her time, and read from Spain to India to the Philippines, many people do not know much about this woman other than wondering casually who is behind the face on the Mexican 200-peso note.

Juana Inés de Asbaje Ramírez de Santillana was born in colonial Mexico a full century after the Aztec Conquest. Juana’s mother, Isabel Ramírez de Santillana, never married and had five other children from two different men. Although somewhat scandalous for 17th Century New Spain, Juana’s mother made do as she was from a family of modest means. Young Juana’s maternal grandfather, the Andalusia-born Pedro Ramírez de Santillana owned two profitable haciendas. Juana’s mother, Isabel, managed the hacienda at Panoayán. Juana never knew her father, a Spanish military captain from the Basque region named Pedro Manuel de Asbaje. As Juana’s father was from Spain and her mother was Spanish born in the New World, Juana was considered criolla in the social hierarchy of colonial Mexico.

As a young girl Juana spent a great deal of time in her grandfather’s very extensive library. Her yearning for knowledge led her to follow her older sister to school to eavesdrop on lessons. By the age of three Juana could read Latin and by five she was able to understand the various ledgers and accounts connected with the finances of the hacienda. The budding poet wrote her first poem by the age of 8. In her grandfather’s vast book collection Juana discovered a work on the grammar of Nahuatl, the native language of the Aztecs. Within a year, likely with some help of native speakers in her life, Juana mastered this indigenous language and would later even write poetry in it. Modern-day authors who want to classify Juana as “oppressed” or “marginalized” claim that she learned Nahuatl to get a better understanding of her indigenous roots. This is not true. As stated earlier, the Ramírez and Asbaje families were pure Spanish. Juana learned the Aztec language because it was widely used around her and depending on the viceroy in charge at any given time, Nahuatl was an official language of New Spain, alongside Spanish. Besides, in that massive library of her grandfather’s there was most likely a book or two of poetry written in Nahuatl. Many do not realize that in Mexico there was a highly refined Aztec literary tradition that predated the Spanish and continued well after the Conquest. Juana was simply continuing the Nahuatl tradition and was adding work to it, respectfully paying homage to an ancient art form of the land to which she was born.

As a young girl Juana spent a great deal of time in her grandfather’s very extensive library. Her yearning for knowledge led her to follow her older sister to school to eavesdrop on lessons. By the age of three Juana could read Latin and by five she was able to understand the various ledgers and accounts connected with the finances of the hacienda. The budding poet wrote her first poem by the age of 8. In her grandfather’s vast book collection Juana discovered a work on the grammar of Nahuatl, the native language of the Aztecs. Within a year, likely with some help of native speakers in her life, Juana mastered this indigenous language and would later even write poetry in it. Modern-day authors who want to classify Juana as “oppressed” or “marginalized” claim that she learned Nahuatl to get a better understanding of her indigenous roots. This is not true. As stated earlier, the Ramírez and Asbaje families were pure Spanish. Juana learned the Aztec language because it was widely used around her and depending on the viceroy in charge at any given time, Nahuatl was an official language of New Spain, alongside Spanish. Besides, in that massive library of her grandfather’s there was most likely a book or two of poetry written in Nahuatl. Many do not realize that in Mexico there was a highly refined Aztec literary tradition that predated the Spanish and continued well after the Conquest. Juana was simply continuing the Nahuatl tradition and was adding work to it, respectfully paying homage to an ancient art form of the land to which she was born.

By sixteen, Isabel Ramírez decided to send Juana to Mexico City. Juana wanted to go beyond the family library and receive a formal higher education which was not permitted for girls at the time. She even told her mother that she would cut her hair and dress as a boy just to get into school. Isabel Ramírez used some old family connections to get Juana a position as a lady-in-waiting at the viceregal court. She immediately came under the protection of the viceroy’s wife, Leonor del Carretto, the daughter of the esteemed Italian Marquess of Grana and Knight of the Golden Fleece, Francesco del Carretto. Leonor and Juana became fast friends. The viceroy’s wife was impressed with the teenager’s broad and deep knowledge of many subjects. While at court, the young Juana dazzled courtesans with her plays and poetry. The viceroy at the time, Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, Marquess of Mancera, decided to put the girl to a test. He gathered together a group of highly respected mathematicians, theologians, jurists and philosophers to ask Juana a series of questions. She solved every math problem correctly and answered every query to the experts’ satisfaction. An observer of this literal inquisition remarked that seeing Juana match wits with this learned group was like watching “a royal galleon fending off a few canoes.” By her late teens Juana caught the eye of many potential suitors of very high station in colonial society and her writings started to become popular among the educated class of New Spain. Some of what she wrote was considered controversial and way ahead of its time, especially her writings about sexist double standards and the unequal treatment of men and women. Given her outspoken observations, some consider Juana to be the New World’s very first feminist.

Following are stanzas from Sor Juana’s poem “You Foolish Men”:

You foolish men who lay

the guilt on women,

not seeing you’re the cause

of the very thing you blame;

if you invite their disdain

with measureless desire

why wish they well behave

if you incite to ill.

You fight their stubbornness,

then, weightily,

you say it was their lightness

when it was your guile.

In all your crazy shows

you act just like a child

who plays the bogeyman

of which he’s then afraid.

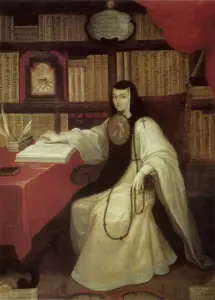

Juana’s primary concern was learning, and since formal higher education and university life were off limits to her, she found refuge in the only other place available to her: The Church, where she set out on a path to become a cloistered nun. In the year 1667 Juana de Asbaje entered the Convent of Saint Joseph, a community of discalced Carmelite nuns and stayed there for a few months. As the community had very strict rules, Juana transferred to another convent belonging the hermetical Order of Saint Jerome, also known as the Hieronymites. With their more relaxed rules, Juana was allowed to indulge in her intellectual curiosities, write and study for hours on end. It was there, after she took her vows, where she became Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. While cloistered in the convent, she turned her cell into a library and a salon where she received intellectuals, nobles and other elites of New Spain. The viceroy and his wife continued their contact with Sor Juana and became her loyal patrons, helping her writings get broad exposure in Spain and throughout the Spanish Empire. She also had the unlimited financial support of Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, the daughter of a powerful Italian duke. Although Sor Juana couldn’t leave the convent she had the best of all worlds: She had intense periods of solitude for writing, learning and contemplation, and because she had a degree of fame from her writings, she interacted with fascinating people who visited her and enriched her, causing her to grow even more intellectually.

Juana’s primary concern was learning, and since formal higher education and university life were off limits to her, she found refuge in the only other place available to her: The Church, where she set out on a path to become a cloistered nun. In the year 1667 Juana de Asbaje entered the Convent of Saint Joseph, a community of discalced Carmelite nuns and stayed there for a few months. As the community had very strict rules, Juana transferred to another convent belonging the hermetical Order of Saint Jerome, also known as the Hieronymites. With their more relaxed rules, Juana was allowed to indulge in her intellectual curiosities, write and study for hours on end. It was there, after she took her vows, where she became Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. While cloistered in the convent, she turned her cell into a library and a salon where she received intellectuals, nobles and other elites of New Spain. The viceroy and his wife continued their contact with Sor Juana and became her loyal patrons, helping her writings get broad exposure in Spain and throughout the Spanish Empire. She also had the unlimited financial support of Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, the daughter of a powerful Italian duke. Although Sor Juana couldn’t leave the convent she had the best of all worlds: She had intense periods of solitude for writing, learning and contemplation, and because she had a degree of fame from her writings, she interacted with fascinating people who visited her and enriched her, causing her to grow even more intellectually.

Sor Juana wrote volumes and her favorite form was poetry, specifically in silvas and villancicos. A silva is a poem using 7- and 11-syllable lines, the majority of which rhyme, although there is no fixed order or rhyme, and there are no fixed number of lines. This poetry form is considered very aristocratic and for people of higher rank. These poems are often full of high emotion and detailed description. A villancico is a more common type of verse which traces its origins back to music from medieval dance forms in Spain and Portugal. This poetry includes a repeatable refrain in between stanzas. In Sor Juana’s time, villancicos were mostly religious and recited or sung during saints’ days or other church feasts. The only musical work of Sor Juana’s to survive to the present day is a four-part villancico now in the archives in the Metropolitan Cathedral in Guatemala City. The name of the composition is Madre, la de los primores, or loosely translated into English, “Mother, the one of the most delicate.” In addition to the massive amount of poetry she left behind, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz composed many plays. Besides her many dramas, Sor Juana’s notable comedies include, Pawns of a House and Love is but a Labyrinth. Critics consider Pawns of a House to be Sor Juana’s greatest work. The story is a comedy of errors about two couples who are in love but cannot yet be together. It involves marital intrigue and explores complicated relationships all set to the background of the ever-evolving complex society of urban colonial Mexico. In addition to the poems, the plays and the music, Sor Juana also wrote essays on society and religion that sometimes caught the eyes of those in authority.

One private essay she wrote critiquing the sermon of a powerful Portuguese Jesuit got the famous nun into a bit of trouble when it was made public. The Bishop of Puebla at the time, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, published Sor Juana’s essay without her permission under a pseudonym, Sor Filotea. The essay was seen as a criticism of the hierarchical structure of the church. In a somewhat passive-aggressive move, after he published Sor Juana’s essay under a fake name, the bishop published his critique of that essay. In this critique he said that the female writer, as a woman, should devote her life to prayer and service and should give up her writing. Sor Juana watched this play out and decided to write a public response called, Reply to Sister Filotea. In this response she defended a woman’s right to an education and insisted that women be leaders in higher education, among other things. The response caught the attention of the Archbishop of Mexico and other higher-up church officials who then wished to censure Sor Juana. By 1693 the literary nun stopped writing as part of her penance to atone for her “waywardness.” A document dating to 1694 describing Sor Juana’s atonement is signed by the nun. She doesn’t use her name, but writes, “Yo, la Peor de todas,” “I, the worst of all women.” As part of her penance, she sold off all of her books, said to have numbered over 4,000 volumes. She also had to get rid of all of her scientific and musical instruments, all drawings, charts, and assorted papers, including over 100 unpublished works, most of which do not survive to this day. Stripped to nothing, Sor Juana was tasked with tending to the sick, specifically the most ill of her own order in the convent. A little over a year after she was forced to give up everything, on April 17, 1695, she was stricken with the plague and died. The poet and controversial thinker once known throughout the Spanish literary world had passed away in obscurity. Centuries later, scholars and literary critics are still trying to understand thoroughly this monumental intellectual and important underrated historical figure.

One private essay she wrote critiquing the sermon of a powerful Portuguese Jesuit got the famous nun into a bit of trouble when it was made public. The Bishop of Puebla at the time, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, published Sor Juana’s essay without her permission under a pseudonym, Sor Filotea. The essay was seen as a criticism of the hierarchical structure of the church. In a somewhat passive-aggressive move, after he published Sor Juana’s essay under a fake name, the bishop published his critique of that essay. In this critique he said that the female writer, as a woman, should devote her life to prayer and service and should give up her writing. Sor Juana watched this play out and decided to write a public response called, Reply to Sister Filotea. In this response she defended a woman’s right to an education and insisted that women be leaders in higher education, among other things. The response caught the attention of the Archbishop of Mexico and other higher-up church officials who then wished to censure Sor Juana. By 1693 the literary nun stopped writing as part of her penance to atone for her “waywardness.” A document dating to 1694 describing Sor Juana’s atonement is signed by the nun. She doesn’t use her name, but writes, “Yo, la Peor de todas,” “I, the worst of all women.” As part of her penance, she sold off all of her books, said to have numbered over 4,000 volumes. She also had to get rid of all of her scientific and musical instruments, all drawings, charts, and assorted papers, including over 100 unpublished works, most of which do not survive to this day. Stripped to nothing, Sor Juana was tasked with tending to the sick, specifically the most ill of her own order in the convent. A little over a year after she was forced to give up everything, on April 17, 1695, she was stricken with the plague and died. The poet and controversial thinker once known throughout the Spanish literary world had passed away in obscurity. Centuries later, scholars and literary critics are still trying to understand thoroughly this monumental intellectual and important underrated historical figure.

REFERENCES

Paz, Octavio. Sor Juana. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. We are an Amazon affiliate. Purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2wdkrnc