Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1943 and the world was at war. Troops of Hitler’s Third Reich occupied the Ukraine and a special unit commanded by Heinz Brucher was sent to retrieve the samples, papers and experiments of a Soviet botanist and geneticist by the name of Nikolai Vasilov. Ironically, Vasilov had been arrested by Soviet leader Josef Stalin two years earlier for disagreeing with a type of science supported by the state, and while Brucher’s men crated up Vasilov’s work the famous scientist languished in a Siberian gulag where he would not live to see the end of 1943 or the completion of his work. The Germans carted up everything they could and transported it to a 16th Century castle just outside of Graz in Nazi-occupied Austria where Heinrich Himmler had established the SS Institute for Plant Genetics. Among the tens of thousands of seeds seized by the Third Reich and taken to Austria were many varieties of maize, known to North American English speakers as “corn,” along with samples of a Mexican grass-like grain called teosinte. Vasilov had collected the seeds from 1924-1935 while serving as head of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Leningrad. He had sent expeditions all over the world to gather the seeds for his collection and had special interest in Mexico and in tracing the origins of maize. In 1931 he was the first person to propose that maize had a wild ancestor known to the Aztecs as teosinte and set out to discover the exact geographic location of the first domesticated corn ever grown by man. The following year, 1932, Vasilov’s work was supported and confirmed by American Nobel Prize winner George Beadle. Modern genetic research combined with archaeological studies also support Vasilov’s conclusions and has further determined the exact part of Mexico where corn was first raised as a domesticated crop.

The year was 1943 and the world was at war. Troops of Hitler’s Third Reich occupied the Ukraine and a special unit commanded by Heinz Brucher was sent to retrieve the samples, papers and experiments of a Soviet botanist and geneticist by the name of Nikolai Vasilov. Ironically, Vasilov had been arrested by Soviet leader Josef Stalin two years earlier for disagreeing with a type of science supported by the state, and while Brucher’s men crated up Vasilov’s work the famous scientist languished in a Siberian gulag where he would not live to see the end of 1943 or the completion of his work. The Germans carted up everything they could and transported it to a 16th Century castle just outside of Graz in Nazi-occupied Austria where Heinrich Himmler had established the SS Institute for Plant Genetics. Among the tens of thousands of seeds seized by the Third Reich and taken to Austria were many varieties of maize, known to North American English speakers as “corn,” along with samples of a Mexican grass-like grain called teosinte. Vasilov had collected the seeds from 1924-1935 while serving as head of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Leningrad. He had sent expeditions all over the world to gather the seeds for his collection and had special interest in Mexico and in tracing the origins of maize. In 1931 he was the first person to propose that maize had a wild ancestor known to the Aztecs as teosinte and set out to discover the exact geographic location of the first domesticated corn ever grown by man. The following year, 1932, Vasilov’s work was supported and confirmed by American Nobel Prize winner George Beadle. Modern genetic research combined with archaeological studies also support Vasilov’s conclusions and has further determined the exact part of Mexico where corn was first raised as a domesticated crop.

In the April 2002 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Japanese researcher Yoshohiro Matsuoka and colleagues published a paper of a study conducted to answer two questions: Where did maize specifically first originate? And, did maize have one point of origin or several points of origin? Because of the many modern varieties of corn throughout the world it has long been proposed that maize developed in different areas and across time. Matsuoka and his research team sampled 193 corn plants from “eastern North America, the deserts of Arizona, the highlands and lowlands of Mexico and Guatemala, the Caribbean Islands, the rainforest of the Amazon Basin, and regions of the Andes Mountains that exceed 3,500 meters in elevation.” The team also looked at 71 teosinte plants from various regions of Mexico and Guatemala, where the grain exists as a native plant species. Their analysis concluded that maize had only one domestication, and this occurred somewhere in the Balsas River drainage area in the modern Mexican states of Puebla and Guerrero around 7200 BC. In a cave near Iguala, Guerrero, archaeologists found stone milling tools with corn residue on them dating back to 6700 BC. By 5000 BC, maize had spread throughout most of Mexico, Central America and northern South America. Corn became a major staple food in these areas and with agriculture came a settled population and later urbanization and complex societies. By 1400 BC we see the beginnings of the Olmec civilization on the gulf coast of Mexico, which is considered ancient Mexico’s first civilization, and it would have never been possible without a stable food source.

In the April 2002 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Japanese researcher Yoshohiro Matsuoka and colleagues published a paper of a study conducted to answer two questions: Where did maize specifically first originate? And, did maize have one point of origin or several points of origin? Because of the many modern varieties of corn throughout the world it has long been proposed that maize developed in different areas and across time. Matsuoka and his research team sampled 193 corn plants from “eastern North America, the deserts of Arizona, the highlands and lowlands of Mexico and Guatemala, the Caribbean Islands, the rainforest of the Amazon Basin, and regions of the Andes Mountains that exceed 3,500 meters in elevation.” The team also looked at 71 teosinte plants from various regions of Mexico and Guatemala, where the grain exists as a native plant species. Their analysis concluded that maize had only one domestication, and this occurred somewhere in the Balsas River drainage area in the modern Mexican states of Puebla and Guerrero around 7200 BC. In a cave near Iguala, Guerrero, archaeologists found stone milling tools with corn residue on them dating back to 6700 BC. By 5000 BC, maize had spread throughout most of Mexico, Central America and northern South America. Corn became a major staple food in these areas and with agriculture came a settled population and later urbanization and complex societies. By 1400 BC we see the beginnings of the Olmec civilization on the gulf coast of Mexico, which is considered ancient Mexico’s first civilization, and it would have never been possible without a stable food source.

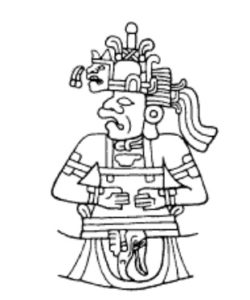

As corn was vitally important to the ancient Mexicans, we see corn emphasized in the various religions of pre-Hispanic peoples. The Olmecs, Zapotecs, Maya, Aztecs and many other groups had dedicated corn deities. Because the Maya left behind a written language along with many ruins and because the Aztecs were a living civilization at the time of the Spanish contact, much is known about the corn deities of these two peoples. To the Maya, corn was a very important part of the creation story. We see in the Popol Vuh, that it took the gods three attempts to create man. They first tried mud, then wood, but man was only fully human when they combined two types of cornmeal and breathed life into him. The Maya maize god was male but the spirit of the corn in oral tradition was female. In the monumental architecture and in the Mayan bark books called codices, the god of corn was depicted in two ways: with a shaved head like a medieval Christian friar, or covered in leaves. When the god is represented as foliated, or covered in leaves, he tends to serve limited functions. When the shaved-head depiction is present, the maize god takes on a wide variety of attributes and functions. It is in this form where the maize deity is associated with Maya queens and this may tie in to the oral tradition of the spirit of the corn plant being female. The purpose of this shaved head deity is still being debated by archaeologists and other researchers.

As corn was vitally important to the ancient Mexicans, we see corn emphasized in the various religions of pre-Hispanic peoples. The Olmecs, Zapotecs, Maya, Aztecs and many other groups had dedicated corn deities. Because the Maya left behind a written language along with many ruins and because the Aztecs were a living civilization at the time of the Spanish contact, much is known about the corn deities of these two peoples. To the Maya, corn was a very important part of the creation story. We see in the Popol Vuh, that it took the gods three attempts to create man. They first tried mud, then wood, but man was only fully human when they combined two types of cornmeal and breathed life into him. The Maya maize god was male but the spirit of the corn in oral tradition was female. In the monumental architecture and in the Mayan bark books called codices, the god of corn was depicted in two ways: with a shaved head like a medieval Christian friar, or covered in leaves. When the god is represented as foliated, or covered in leaves, he tends to serve limited functions. When the shaved-head depiction is present, the maize god takes on a wide variety of attributes and functions. It is in this form where the maize deity is associated with Maya queens and this may tie in to the oral tradition of the spirit of the corn plant being female. The purpose of this shaved head deity is still being debated by archaeologists and other researchers.

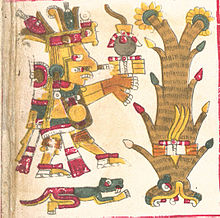

According to the Aztecs, corn was brought to the earth by the god Quetzalcoatl and is associated with the star cluster we call the Pleiades. The Aztec god of maize is named Centeotl, which comes from two Nahuatl words, cintli, which means, “dried corn on the cob,” and teotl, which means “deity.” In one version of the maize god myth, Centeotl is the son of the earth goddess and the planet Mercury. In another version, he is the son of Xochiquetzal, the Aztec goddess of fertility, beauty and feminine power. He is associated with days that have the number 7 in them and on the Aztec  calendar he is the Fourth Lord of the Night. Centeotl is usually represented to be a young man of yellow color with maize in his headdress and black lines going down either side of his face. The black lines are also found on the foliated depiction of the Maya corn god. To appease Centeotl and to ensure a good corn crop, 5 older women from a village would go out to the cornfields at the beginning of the harvest to pick one corn cob each, wrapping it carefully and carrying it on her back as she would a newborn baby. In the village the 5 cobs would be placed in a basket for the whole year as an offering to Centeotl and to insure good harvests in the future. Each of the five ears of corn were dedicated to a separate goddess involved in the growing and harvesting of corn or they may have been connected to the spirits of the cornfield, researchers are not quite sure. The Aztec goddess of agriculture, Chicomecoatl, logically, is also associated with the growing of corn and she is often referred to as “the princess of the unripe maize.” Dances were usually performed by the Aztecs at planting time and also around the time of the harvest. Corn was such an important part of life in ancient Mexico that it is not surprising that so much myth and ritual surround this essential source of food.

calendar he is the Fourth Lord of the Night. Centeotl is usually represented to be a young man of yellow color with maize in his headdress and black lines going down either side of his face. The black lines are also found on the foliated depiction of the Maya corn god. To appease Centeotl and to ensure a good corn crop, 5 older women from a village would go out to the cornfields at the beginning of the harvest to pick one corn cob each, wrapping it carefully and carrying it on her back as she would a newborn baby. In the village the 5 cobs would be placed in a basket for the whole year as an offering to Centeotl and to insure good harvests in the future. Each of the five ears of corn were dedicated to a separate goddess involved in the growing and harvesting of corn or they may have been connected to the spirits of the cornfield, researchers are not quite sure. The Aztec goddess of agriculture, Chicomecoatl, logically, is also associated with the growing of corn and she is often referred to as “the princess of the unripe maize.” Dances were usually performed by the Aztecs at planting time and also around the time of the harvest. Corn was such an important part of life in ancient Mexico that it is not surprising that so much myth and ritual surround this essential source of food.

When Columbus and other early European explorers first arrived in the Caribbean, corn then became known for the first time outside the Americas. The Taíno Indians of the West Indies called the plant mahiz and it entered the Spanish language as maíz and later English as “maize.” In the first few years of their encounter with maize the Spanish were reluctant to eat it. They believed that if they ate as the Indians did and lived as they did that they might actually turn into Indians themselves. Perhaps out of practicality, these notions evaporated and corn cultivation quickly spread to southern Europe and West Africa. Within 200 years of its leaving the Americas, maize was found growing in all parts of the world that would sustain it. By weight, today corn is the most widely produced grain in all the world, with the United States, China and Brazil being the top corn producers. Mexico is the world’s 7th largest producer of maize and because of the North American Free Trade Agreement and farm subsidies given to American farmers, Mexico actually imports corn from the United States at a lower price than what it costs to produce it in Mexico.

When Columbus and other early European explorers first arrived in the Caribbean, corn then became known for the first time outside the Americas. The Taíno Indians of the West Indies called the plant mahiz and it entered the Spanish language as maíz and later English as “maize.” In the first few years of their encounter with maize the Spanish were reluctant to eat it. They believed that if they ate as the Indians did and lived as they did that they might actually turn into Indians themselves. Perhaps out of practicality, these notions evaporated and corn cultivation quickly spread to southern Europe and West Africa. Within 200 years of its leaving the Americas, maize was found growing in all parts of the world that would sustain it. By weight, today corn is the most widely produced grain in all the world, with the United States, China and Brazil being the top corn producers. Mexico is the world’s 7th largest producer of maize and because of the North American Free Trade Agreement and farm subsidies given to American farmers, Mexico actually imports corn from the United States at a lower price than what it costs to produce it in Mexico.

To this day corn remains the basis for Mexican cuisine and a staple in the Mexican diet. There is no meal served that doesn’t include some sort of corn product or byproduct. Tortillas, posole and tamales are all familiar around the world and so are the dishes including them such as enchiladas, tacos and quesadillas. Maize is so important in the daily life of Mexicans that the price of cornmeal used in making tortillas is a main economic indicator in Mexico, much like the price of gasoline is for people in the United States. A byproduct of corn growing seen as a delicacy in Mexico but seen as a blight in the US is huitlacoche, called “corn smut” in English. Huitlacoche grows on the kernels of the corn and as it is a fungus it looks somewhat like a mushroom. It is used by Mexicans in soups, tacos and quesadillas and has been described as having a “woody”, “earthy” and “mushroom-like” flavor to it. In the United States, where corn smut has been mostly eradicated, there was a movement in the late 1980s during a wave of “fusion cuisine” that an attempt was made to rename huitlacoche from “corn smut” to “Mexican truffle.” This name did not stick.

The selective breeding over thousands of years for more desirable crops of maize, starting with human changes to teosinte many millennia ago, has entered a new era in recent times. One of the biggest controversies in the past few decades with regard to the food supply has been the use of genetically modified organisms or GMOs. Because corn is such an important crop worldwide, it has been subject to many different types of genetic modifications. These modifications are made to resist pests and herbicides and to create a larger yield. GMO use has raised controversy for supposedly having adverse health effects on humans and a destructive impact on insect populations. Cross-contamination with non-GMO crops is also an issue. Mexico has banned companies like Monsanto from importing GMO corn seeds and has forbidden companies from starting “pilot projects” of small farms to “test” the growing of GMO corn in Mexico. The process has been bogged down in Mexican bureaucracy for years, but the truth be told, most people in Mexico don’t want to have anything to do with growing genetically altered versions of their iconic staple crop. Currently there are no GMO corn crops growing in the country where maize originated and Mexicans, for the most part, are happy with that. Perhaps the Aztec god Centeotl can keep the American companies at bay for just a little while longer.

The selective breeding over thousands of years for more desirable crops of maize, starting with human changes to teosinte many millennia ago, has entered a new era in recent times. One of the biggest controversies in the past few decades with regard to the food supply has been the use of genetically modified organisms or GMOs. Because corn is such an important crop worldwide, it has been subject to many different types of genetic modifications. These modifications are made to resist pests and herbicides and to create a larger yield. GMO use has raised controversy for supposedly having adverse health effects on humans and a destructive impact on insect populations. Cross-contamination with non-GMO crops is also an issue. Mexico has banned companies like Monsanto from importing GMO corn seeds and has forbidden companies from starting “pilot projects” of small farms to “test” the growing of GMO corn in Mexico. The process has been bogged down in Mexican bureaucracy for years, but the truth be told, most people in Mexico don’t want to have anything to do with growing genetically altered versions of their iconic staple crop. Currently there are no GMO corn crops growing in the country where maize originated and Mexicans, for the most part, are happy with that. Perhaps the Aztec god Centeotl can keep the American companies at bay for just a little while longer.

REFERENCES

Taube, Karl. “The Olmec Maize God: The Face of Corn in Formative Mesoamerica.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 29/30, 1996, pp. 39–81.

, et al. “A Single Domestication for Maize Shown by Multilocus Microsatellite Genotyping” PNAS 2002 99 (9) 6080–6084; doi:10.1073/pnas.052125199

Wikipedia

2 thoughts on “The Story of Maize, Mexico’s Gift to the World”

I enjoyed this episode and the podcast in general! A friendly suggestion to seek out the research of Richard MacNeish on the subject of the domestication of corn in the Tehuacán Valley region.

Will do. Thanks for the suggestion!