Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was September 1, 1519. On their overland march to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, Hernán Cortés and the Spaniards, accompanied by dozens of indigenous allies, had just crossed into Tlaxcalan territory. The Tlaxcalans had known of the approach of the newcomers for days and were ready to receive them. The welcome of the strangers was mixed. Being hospitable, the Tlaxcalans gave Cortés a beautifully fashioned gold necklace along with bolts of handwoven cloth and two slave girls. As the Tlaxcalans were at perpetual war with the Aztec Empire, they were wary of the strangers who had among them natives from Cempoala and Xocotlan which were towns that were part of a kingdom that paid tribute to the Aztecs. Many Tlaxcalans believed that the Spanish were intent on attacking them, and thus prepared for war. The Spanish had a single-minded goal, though, and that was to pass through the Tlaxcalan lands to get to the Aztec capital. As Cortés marched deeper into Tlaxcalan territory, he met with more resistance, until he and his men were attacked by a few dozen Tlaxcalan warriors and their Otomí allies. The skirmish soon involved others. One of Cortés’ men, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, wrote about this battle in his diaries that later were published into a book. Díaz writes:

The date was September 1, 1519. On their overland march to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, Hernán Cortés and the Spaniards, accompanied by dozens of indigenous allies, had just crossed into Tlaxcalan territory. The Tlaxcalans had known of the approach of the newcomers for days and were ready to receive them. The welcome of the strangers was mixed. Being hospitable, the Tlaxcalans gave Cortés a beautifully fashioned gold necklace along with bolts of handwoven cloth and two slave girls. As the Tlaxcalans were at perpetual war with the Aztec Empire, they were wary of the strangers who had among them natives from Cempoala and Xocotlan which were towns that were part of a kingdom that paid tribute to the Aztecs. Many Tlaxcalans believed that the Spanish were intent on attacking them, and thus prepared for war. The Spanish had a single-minded goal, though, and that was to pass through the Tlaxcalan lands to get to the Aztec capital. As Cortés marched deeper into Tlaxcalan territory, he met with more resistance, until he and his men were attacked by a few dozen Tlaxcalan warriors and their Otomí allies. The skirmish soon involved others. One of Cortés’ men, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, wrote about this battle in his diaries that later were published into a book. Díaz writes:

“A squadron of Tlaxcalans, more than three thousand strong, which was lying in ambush, fell on our men all of a sudden, with great fury and began to shower arrows on our horsemen who were now all together; and they made a good fight with their arrows and fire-hardened darts, and did wonders with their two-handed swords. At this moment we came up with artillery, muskets and crossbows, and little by little the Indians gave way, but they had kept their ranks and fought well for a considerable time.”

Díaz mentions a second battle, much larger than the first that took place a few days later. In this battle the Tlaxcalans managed to muster tens of thousands of warriors under the leadership of a person Díaz called Xicotenga whose Nahuatl name was Xicontencatl. This war leader is referred to “Xicontencatl the Younger” in the history books because he was son of a great Tlaxcalan cacique by the same name which history has labeled “Xicontencatl the Elder.” The Elder, who was well into his 90s when the Spanish arrived, had a plan to involve the foreigners that didn’t involve war, at least not with the Republic of Tlaxcala. After the second major confrontation between the Spaniards and Tlaxalans, the Spanish sent emissaries of peace to the Tlaxcalan capital city. Xicontencatl the Elder and other senior statesmen were wanting peace with these invaders, too, and they also saw Cortés’ arrival as an opportunity. The Tlaxcalans knew these strangers were headed to the  Aztec capital to see Montezuma, their sworn enemy. The Xicontencatl told his son to cease all hostilities at once and to invite the Spaniards to the capital city. In a matter of days, the Spanish and the Tlaxcalan State formed an alliance. Cortés marched with his new allies to Tenochtitlán and with his tens of thousands of helpers, he eventually captured the Aztec capital and toppled the mighty empire. Xicontencatl the Elder was 97 years old when the Spanish gained full control of the Valley of Mexico and one of Mesoamerica’s most important and beloved leaders died soon after. Xicontencatl’s legacy was immediate: The King of Spain granted the Tlaxcalans special privileges for their role in the Conquest of Mexico. While most indigenous people were not allowed to carry firearms or ride horses, the Spanish granted the Tlaxcalans the rights to do those things. Members of the Tlaxcalan nobility were allowed to keep their titles and their lands, and the Tlaxcalan state was allowed to retain a great degree of autonomy within the Spanish Empire. This is one of the reasons why the modern Mexican state of Tlaxcala is so small: it has maintained the same borders as it had since ancient times.

Aztec capital to see Montezuma, their sworn enemy. The Xicontencatl told his son to cease all hostilities at once and to invite the Spaniards to the capital city. In a matter of days, the Spanish and the Tlaxcalan State formed an alliance. Cortés marched with his new allies to Tenochtitlán and with his tens of thousands of helpers, he eventually captured the Aztec capital and toppled the mighty empire. Xicontencatl the Elder was 97 years old when the Spanish gained full control of the Valley of Mexico and one of Mesoamerica’s most important and beloved leaders died soon after. Xicontencatl’s legacy was immediate: The King of Spain granted the Tlaxcalans special privileges for their role in the Conquest of Mexico. While most indigenous people were not allowed to carry firearms or ride horses, the Spanish granted the Tlaxcalans the rights to do those things. Members of the Tlaxcalan nobility were allowed to keep their titles and their lands, and the Tlaxcalan state was allowed to retain a great degree of autonomy within the Spanish Empire. This is one of the reasons why the modern Mexican state of Tlaxcala is so small: it has maintained the same borders as it had since ancient times.

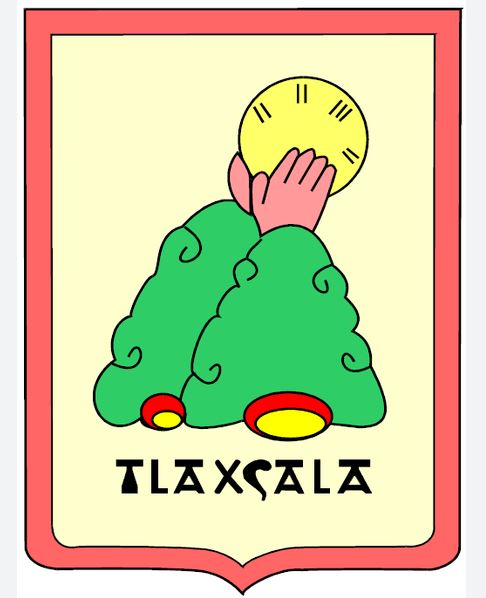

What is the history of this unique and special place? The Tlaxcalans are a Nahua-speaking people who arrived in central Mexico with what would later be called the Aztecs and related groups. The Tlaxcalans settled on the eastern shores of Lake Texcoco. After several generations of living in that area, competing groups drove most of the Tlaxcalans east, and they split into three separate bands along the way. One small group remained in the Valley of Mexico but later joined the other three bands in the territory that would later become the political entity called the State of Tlaxcala. When this ethnic group was all settled down and established, they started calling themselves Tlaxcaltecas which came from the name of the valley where they had moved to, Tlaxcala, which loosely translates from Nahuatl to English as “The Place of the Corn Tortillas.” The name glyph for Tlaxcala shows two hands making a corn tortilla between two green mountains.

Many historians refer to this independent state as a “confederation,” a “confederacy,” or a “republic” instead of a “kingdom” or “empire” because of its structure that was somewhat unique in ancient Mexico. The Tlaxcalans themselves referred to their country as Tlahtōlōyān Tlaxcallan. The four bands each had a capital city. The first three bands were headquartered at Tepeticpac, Ocotelolco and Tizatlan. The fourth group which later joined the first three established themselves at Quiahuiztlan. Each of these cities administered smaller villages, forts, trading posts and communal areas. The four groups came together as the State or Republic of Tlaxcala in their national administrative council sometimes referred to in history books as the Tlaxcala Senate. This body was comprised of 50 to 200 teteuctin, who were appointed representatives and met periodically to discuss matters that affected the whole of Tlaxcala. The singular version of the word teteuctin is teuctli. A teuctli may have been selected from either the noble or commoner classes and his appointment was usually made because of his service to the state. A teuctli usually was elected to the council because of distinguished service in warfare, but not always. Village leaders or even engineers could serve as representatives to the national council. There were respected elder leaders from old noble families in the administrative body of the Tlaxcala Republic such as the ninety-something-year-old Xicontencatl mentioned previously, but the whole point of the council was to ensure that all voices throughout the republic were heard, and major issues were discussed and debated thoroughly. The de-facto capital of the Republic of Tlaxcala was Tizatlan where the council met and where the noble family headed by Xicontencatl ruled. When the Spanish arrived, they just assumed that Xicontencatl the Elder was King of Tlaxcala, but he technically was not. He was just a senior noble member of the Tlaxcala Senate.

Many historians refer to this independent state as a “confederation,” a “confederacy,” or a “republic” instead of a “kingdom” or “empire” because of its structure that was somewhat unique in ancient Mexico. The Tlaxcalans themselves referred to their country as Tlahtōlōyān Tlaxcallan. The four bands each had a capital city. The first three bands were headquartered at Tepeticpac, Ocotelolco and Tizatlan. The fourth group which later joined the first three established themselves at Quiahuiztlan. Each of these cities administered smaller villages, forts, trading posts and communal areas. The four groups came together as the State or Republic of Tlaxcala in their national administrative council sometimes referred to in history books as the Tlaxcala Senate. This body was comprised of 50 to 200 teteuctin, who were appointed representatives and met periodically to discuss matters that affected the whole of Tlaxcala. The singular version of the word teteuctin is teuctli. A teuctli may have been selected from either the noble or commoner classes and his appointment was usually made because of his service to the state. A teuctli usually was elected to the council because of distinguished service in warfare, but not always. Village leaders or even engineers could serve as representatives to the national council. There were respected elder leaders from old noble families in the administrative body of the Tlaxcala Republic such as the ninety-something-year-old Xicontencatl mentioned previously, but the whole point of the council was to ensure that all voices throughout the republic were heard, and major issues were discussed and debated thoroughly. The de-facto capital of the Republic of Tlaxcala was Tizatlan where the council met and where the noble family headed by Xicontencatl ruled. When the Spanish arrived, they just assumed that Xicontencatl the Elder was King of Tlaxcala, but he technically was not. He was just a senior noble member of the Tlaxcala Senate.

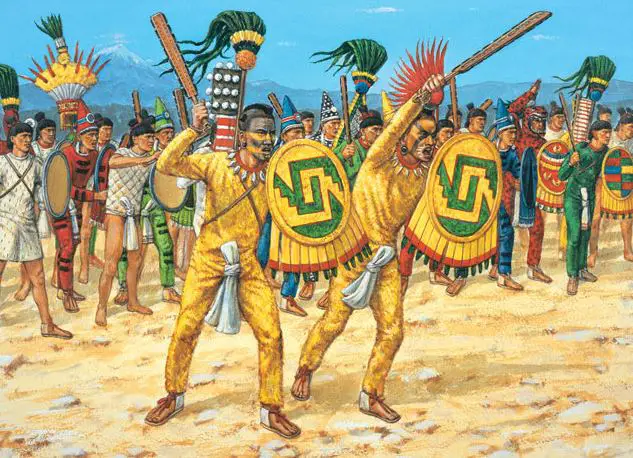

The ancient Republic of Tlaxcala was surrounded by the Aztec Empire and was in a constant state of war with them. Researchers call this series of wars the Flower Wars or the Garland Wars. They had their origins during a great famine that plagued the Aztec capital and the Valley of Mexico in the early 1450s. The priests at Tenochtitlán claimed that the gods needed human sacrifices to end the famine, and regular sacrifices after the famine’s end to ensure that more catastrophes would not come to the Aztec Empire. So, the Aztecs made war against the Tlaxcalans in designated places at designated times for the sole purpose of getting captives for sacrifices. The Tlaxcalans agreed to these periodic Flower Wars instead of risking an all-out assault and takeover from their more powerful and much larger neighbor. The Republic of Tlaxcala was allowed to maintain its status as an independent country as long as it participated in these wars. The combat itself in these wars was different from regular warfare beyond just agreeing to a place and time for the battle. In the Flower War battles darts, throwing spears and bows and arrows were prohibited. Warriors engaged each other in battle with clubs and obsidian knives in a more personal, hand-to-hand sort of way. Unlike traditional warfare, numbers of warriors were also decided upon ahead of time.  The Aztecs and Tlaxcalans matched each other one for one. The battle sites were called cuauhtlalli or yaotlalli and were thought by both sides to be sacred or holy spaces. The Aztecs considered a warrior’s death in a flower war to be more noble than dying in a typical war. The word in Nahuatl for a death during a flower war was, xochimiquiztli, which translates to “flowery death, blissful death, or fortunate death.” Some modern scholars debate the idea that the Flower Wars were used to gather captives for sacrifices. Some researchers believe that the Aztecs wanted to conquer the Tlaxcalans but could not for some reason, and the Flower Wars were used to wear down the Tlaxcalan State. When the Spanish arrived in the Aztec capital as honored guests of Emperor Montezuma, one of Cortés’ officers asked the ruler why the Aztecs didn’t just overrun Tlaxcala, incorporate it into their empire and end the perpetual state of war. The emperor stated that the empire could take over Tlaxcala if it wanted to, but the Flower Wars provided inexperienced soldiers with much-needed real-life training that they could use to fight enemies in other parts of the empire. The Tlaxcalans saw the arrival of the Spanish as an opportunity to end this constant state of war once and for all, and that was one of the reasons why the Tlaxcalan Senate decided to stop fighting with the Spanish and ally with them instead in order to topple their old enemy. Their alliance worked because without the help from the Republic of Tlaxcala and other indigenous allies, the Aztec Empire may never have fallen, at least not from the efforts of Cortés and the Spanish at that time.

The Aztecs and Tlaxcalans matched each other one for one. The battle sites were called cuauhtlalli or yaotlalli and were thought by both sides to be sacred or holy spaces. The Aztecs considered a warrior’s death in a flower war to be more noble than dying in a typical war. The word in Nahuatl for a death during a flower war was, xochimiquiztli, which translates to “flowery death, blissful death, or fortunate death.” Some modern scholars debate the idea that the Flower Wars were used to gather captives for sacrifices. Some researchers believe that the Aztecs wanted to conquer the Tlaxcalans but could not for some reason, and the Flower Wars were used to wear down the Tlaxcalan State. When the Spanish arrived in the Aztec capital as honored guests of Emperor Montezuma, one of Cortés’ officers asked the ruler why the Aztecs didn’t just overrun Tlaxcala, incorporate it into their empire and end the perpetual state of war. The emperor stated that the empire could take over Tlaxcala if it wanted to, but the Flower Wars provided inexperienced soldiers with much-needed real-life training that they could use to fight enemies in other parts of the empire. The Tlaxcalans saw the arrival of the Spanish as an opportunity to end this constant state of war once and for all, and that was one of the reasons why the Tlaxcalan Senate decided to stop fighting with the Spanish and ally with them instead in order to topple their old enemy. Their alliance worked because without the help from the Republic of Tlaxcala and other indigenous allies, the Aztec Empire may never have fallen, at least not from the efforts of Cortés and the Spanish at that time.

As briefly mentioned before, the reward for loyalty to the Spanish against the Aztecs was the granting of privileged or hidalgo status to the Tlaxcalans. Tlaxcala was spared the destruction and pillaging that other parts of Mexico experienced during the Spanish Conquest, and the Tlaxcalans were allowed to preserve their culture, their institutions and their titles of nobility. The Spanish divided the former Tlaxcalan Republic into four señoríos, or fiefdoms, which were ruled by the noble families that had always resided in their respective señorío. As the Tlaxalans were excellent warriors and loyal to the Spanish Crown, the Spanish used them to fight hostile groups such as the Chichimeca, or to serve as examples in other parts of Mexico to other indigenous people. Often, they accompanied new settlers to faraway parts of New Spain. There was even a small Tlaxcalan barrio in Santa Fe, New Mexico in the 1600s. There is no doubt that the influence of this tiny republic could be felt far and wide and had a long-lasting impact on Mexican history.

REFERENCES

Diaz del Castillo, Bernal. Conquest of New Spain. New York: The Folio Society, 1974. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3ZmOP7y