Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

From the larger cities to the small rural areas, most everyone in the country of Mexico today is glued to their electronic devices. Much like in other places on earth, on public transport, in bus stops and subway stations throughout the county people are wired into their smart phones, tablets and mp3 players. These devices help pass the time and occupy the mind and serve to ease the long wait of often unreliable transportation across long or short distances. In a time before the pervasiveness of electronics, Mexicans diverted themselves with historietas, novelas or romanticos, the terms used to describe cheap but artfully illustrated pulp comic books. While waiting for the many buses to take her across the wide expanse of Mexico City, for one peso a maid or factory worker could be transported back in time to a romance in colonial New Spain, or experience the trials and tribulations of an innocent Japanese girl, or laugh at the humorous antics of a mischievous Afro-Mexican boy. The little comic books were once everywhere, and at the height of their popularity, the Mexican presses cranked out hundreds of millions of these delightful pieces of popular culture every year. Those who remember the days of the pulp graphic novels might not know of the most influential person behind this amazing phenomenon. Her mind was a fantasy factory and she built a massive business empire founded on the sparkle of her own imagination. Her name was Yolanda Vargas Dulché.

From the larger cities to the small rural areas, most everyone in the country of Mexico today is glued to their electronic devices. Much like in other places on earth, on public transport, in bus stops and subway stations throughout the county people are wired into their smart phones, tablets and mp3 players. These devices help pass the time and occupy the mind and serve to ease the long wait of often unreliable transportation across long or short distances. In a time before the pervasiveness of electronics, Mexicans diverted themselves with historietas, novelas or romanticos, the terms used to describe cheap but artfully illustrated pulp comic books. While waiting for the many buses to take her across the wide expanse of Mexico City, for one peso a maid or factory worker could be transported back in time to a romance in colonial New Spain, or experience the trials and tribulations of an innocent Japanese girl, or laugh at the humorous antics of a mischievous Afro-Mexican boy. The little comic books were once everywhere, and at the height of their popularity, the Mexican presses cranked out hundreds of millions of these delightful pieces of popular culture every year. Those who remember the days of the pulp graphic novels might not know of the most influential person behind this amazing phenomenon. Her mind was a fantasy factory and she built a massive business empire founded on the sparkle of her own imagination. Her name was Yolanda Vargas Dulché.

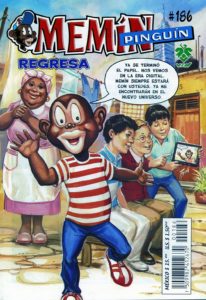

Yolanda Vargas Dulché was born on July 18, 1926 in the Guerrero neighborhood of Mexico City to poor, working class parents, Armando Vargas de la Maza and Josefina Dulché. Yolanda had one sibling a sister named Elba. The family’s unstable economic situation caused Yolanda to move around a lot and she changed schools repeatedly. Her frequent moves – including a brief stint in the United States – exposed Vargas to various elements of Mexican society and would later serve her well in the creation of her fictional characters. In her teen years, her first exposure to the world of the arts was at radio station XEW-AM singing along with her sister, Elba, in a duet called “Rubia y Morena.” Their act teemed up with Mexican songwriter Agustin Lara and the sisters performed in major venues throughout Mexico and in two places abroad: Los Angeles, California and Havana, Cuba. In her 16th year, Vargas began selling her writing, first to the Mexican newspaper El Universal. From there, she wrote full time for the publication Esto, where she started to become interested in the comics genre. In 1943, at the age of 17 she created the character Memín Pinguín, arguably the most popular comic book character of all time in Mexico. The  adventures of this mischievous Afro-Mexican boy appeared in the magazine Pepín, but Memín was so popular that by 1947 he had his own line of pulp comics on every newsstand in Mexico. Vargas had unparalleled success before the age of 20, already the main writer in the most important magazines in Mexico: Pepín and Chamaco. These magazines, of the García Valseca Chain, were daily periodic publications that not only appeared seven days a week, but they even had two Sunday editions each. While writing for these magazines in the 1940s, Yolanda Vargas Dulché also wrote for dramatic radio serials. In 1944 she composed her first complete radio drama called “Celos,” or “Jealousy,” in English. While doing her radio work, Vargas also caught the eye of the Mexican film industry. In 1946, at the age of 20, noted Mexican actor and director Gilberto Martínez Solares contacted Vargas to write the screenplay of the movie, “Cinco rostros de mujer,” or in English “Five Faces of a Woman.” Later that year, she would be asked to write the screenplay of the movie “Zorina.” Back in the world of print, by 1947 Vargas had two of the most popular serial comics in Mexico, Cumbres de ensueños, or “Dream Summits,” in English and Ladronzuela, which loosely translates to “The Pilferer.” The Mexican public was enraptured with Vargas’s work to such a degree that she eventually decided to break away from her employer and founded her own publishing company in 1955 called Editorial Argumentos, partnering with her husband, Guillermo de la Parra.

adventures of this mischievous Afro-Mexican boy appeared in the magazine Pepín, but Memín was so popular that by 1947 he had his own line of pulp comics on every newsstand in Mexico. Vargas had unparalleled success before the age of 20, already the main writer in the most important magazines in Mexico: Pepín and Chamaco. These magazines, of the García Valseca Chain, were daily periodic publications that not only appeared seven days a week, but they even had two Sunday editions each. While writing for these magazines in the 1940s, Yolanda Vargas Dulché also wrote for dramatic radio serials. In 1944 she composed her first complete radio drama called “Celos,” or “Jealousy,” in English. While doing her radio work, Vargas also caught the eye of the Mexican film industry. In 1946, at the age of 20, noted Mexican actor and director Gilberto Martínez Solares contacted Vargas to write the screenplay of the movie, “Cinco rostros de mujer,” or in English “Five Faces of a Woman.” Later that year, she would be asked to write the screenplay of the movie “Zorina.” Back in the world of print, by 1947 Vargas had two of the most popular serial comics in Mexico, Cumbres de ensueños, or “Dream Summits,” in English and Ladronzuela, which loosely translates to “The Pilferer.” The Mexican public was enraptured with Vargas’s work to such a degree that she eventually decided to break away from her employer and founded her own publishing company in 1955 called Editorial Argumentos, partnering with her husband, Guillermo de la Parra.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Editorial Argumentos produced dozens of titles with hundreds of characters that seemed to spring effortlessly from the brilliant mind of Yolanda Vargas Dulché. The most popular title at Editorial Argumentos, without a doubt, was Memín Pinguín. The comic about the sly little black boy was not without its share of controversy, however. At one point it was even boycotted by the Catholic Church. In one issue of the comic, a friend of Memín told him that he wasn’t going to go to Heaven because there were never any depictions of black angels in religious art. Memín responded by saying that if this were the case than he would cause whatever amount of trouble he wanted while he was alive and didn’t have to bother with going to church because he was going to go to hell anyway. Priests and other religious authorities throughout Mexico were outraged, called for the boycott and sales of the Memín comics plummeted. Vargas tried rescuing her brand by creating one comic in which Memín returns to church and together with his friend and a helpful priest, they paint an angel black in one of the church’s religious paintings. At the end of this installment Memín vowed to continue his religious instruction and promised he would behave properly from now on. Vargas’ plan worked, the Catholic Church in Mexico lifted its official boycott of the Memín comic, and sales came back stronger than before.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Editorial Argumentos produced dozens of titles with hundreds of characters that seemed to spring effortlessly from the brilliant mind of Yolanda Vargas Dulché. The most popular title at Editorial Argumentos, without a doubt, was Memín Pinguín. The comic about the sly little black boy was not without its share of controversy, however. At one point it was even boycotted by the Catholic Church. In one issue of the comic, a friend of Memín told him that he wasn’t going to go to Heaven because there were never any depictions of black angels in religious art. Memín responded by saying that if this were the case than he would cause whatever amount of trouble he wanted while he was alive and didn’t have to bother with going to church because he was going to go to hell anyway. Priests and other religious authorities throughout Mexico were outraged, called for the boycott and sales of the Memín comics plummeted. Vargas tried rescuing her brand by creating one comic in which Memín returns to church and together with his friend and a helpful priest, they paint an angel black in one of the church’s religious paintings. At the end of this installment Memín vowed to continue his religious instruction and promised he would behave properly from now on. Vargas’ plan worked, the Catholic Church in Mexico lifted its official boycott of the Memín comic, and sales came back stronger than before.

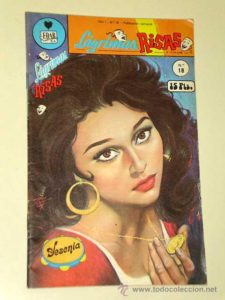

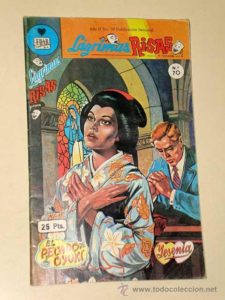

Vargas’ comics were recognizable throughout Mexico and were seen everywhere by the mid 1960s. Editorial Argumentos was selling over one million comic books per week at this time. To give an American number for comparison, the iconic US comic Superman was selling only one million copies per month with 4 times the reader base in the 1960s. Everyone across Mexico knew the titles and waited for the latest installments of their favorite comics to hit the newsstands. During this time, the most popular comic book series was Lágrimas, risas y amor, “Tears, Laughter and Love,” which contained several different stories with characters people followed eagerly every week. Despite the massive growth of her company, Vargas was very hands-on and still wrote the storylines to the multiple titles she created. Her work thoroughly energized her and because of her massive output, Yolanda Vargas Dulché eventually became the third most widely read author in the Spanish language in the world behind the Asturian romance novelist  Corin Tellado and the great Cervantes himself. In Mexico, she was number one. Her fame and more specifically, the medium in which she worked, generated harsh debate. Mexican intellectuals scorned the pulp comics and cheap graphic novels and claimed that the genre was a detriment to society. There was one major result of this comic book phenomenon that these critics were missing. Because of the intense national interest in these fascinating stories accompanied by excellent artwork, illiterate people across Mexico felt like they were missing out on something. Those Mexicans who were unable to read started to become interested in learning how to read. These pulp comics accomplished something that the Mexican Ministry of Education was unable to do. They helped lift tens of millions of Mexicans out of illiteracy. In an interview later in life, Yolanda Vargas Dulché would state, “My critics say they love the people, but they do nothing for them, not even entertain them. I started writing comics because I wanted to reach the masses by speaking to them in their own language, and by dramatizing their own feelings in my stories. I got it, because I looked for diversion and I managed, even for a few moments, to get them out of their great worries, their sorrows, the sadness of their daily lives.”

Corin Tellado and the great Cervantes himself. In Mexico, she was number one. Her fame and more specifically, the medium in which she worked, generated harsh debate. Mexican intellectuals scorned the pulp comics and cheap graphic novels and claimed that the genre was a detriment to society. There was one major result of this comic book phenomenon that these critics were missing. Because of the intense national interest in these fascinating stories accompanied by excellent artwork, illiterate people across Mexico felt like they were missing out on something. Those Mexicans who were unable to read started to become interested in learning how to read. These pulp comics accomplished something that the Mexican Ministry of Education was unable to do. They helped lift tens of millions of Mexicans out of illiteracy. In an interview later in life, Yolanda Vargas Dulché would state, “My critics say they love the people, but they do nothing for them, not even entertain them. I started writing comics because I wanted to reach the masses by speaking to them in their own language, and by dramatizing their own feelings in my stories. I got it, because I looked for diversion and I managed, even for a few moments, to get them out of their great worries, their sorrows, the sadness of their daily lives.”

Vargas and her husband started to kick things up a notch in the late 1960s. Editorial Argumentos became Grupo Editorial Vid and branched out into television soap operas, known in Mexico as telenovelas, and also into film. The plan was to take the comics to the small screen and the silver screen. As she did in the 1940s, Vargas had her hand in writing the screenplays and television scripts and oversaw key elements of the production processes. The titles of the telenovelas and films, which aired all the way through the nineties are familiar to Mexicans to this day: “Ecrucijada,” “Alondra,” “El Pecado de Oyuki,” “El Amor de María Isabel,” “Gabriel y Gabriela,” and “Rubí” among others. Yolanda Vargas’ pride and joy was a film called “Yesenia” about a young girl from an aristocratic family who is raised by a tribe of gypsies. “Yesenia” started as a pulp comic, was made into a telenovela in 1970 and then into a movie. In June of 1979, the film was one of three to be featured during “Mexican Cinema Week in China,” sponsored by the Chinese Ministry of Culture as part of a Chinese-Mexican cultural exchange. “Yesenia” was so popular that audiences lined up for hours to see  it. As it was only showing for a limited time during the Mexican Cinema Week, the Chinese government eventually worked out a deal with Vargas to buy the rights to the film. In 1979 “Yesenia” was the most popular foreign film in the entire People’s Republic. While working on the more cinematic aspects of the company, Grupo Editorial Vid expanded its printed products into foreign markets, notably the Philippines, Spain and the United States. At their peak of comic book production in the 1970s, Yolanda and Guillermo’s company was selling over 800 million copies per year in various parts of the world. The entrepreneurial snowball grew, and it was not before long that Vargas decided to expand her horizons once again.

it. As it was only showing for a limited time during the Mexican Cinema Week, the Chinese government eventually worked out a deal with Vargas to buy the rights to the film. In 1979 “Yesenia” was the most popular foreign film in the entire People’s Republic. While working on the more cinematic aspects of the company, Grupo Editorial Vid expanded its printed products into foreign markets, notably the Philippines, Spain and the United States. At their peak of comic book production in the 1970s, Yolanda and Guillermo’s company was selling over 800 million copies per year in various parts of the world. The entrepreneurial snowball grew, and it was not before long that Vargas decided to expand her horizons once again.

In the early 1980s, Vargas and her husband acquired a hotel chain based in Ixtapa-Zihuatenejo called Hoteles Krystal. Thinking creatively, Vargas assessed the status of this chain and decided to make some changes and expand. She opted to build their first new hotel in the fledgling development called Cancún, on the Caribbean shores of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. Vargas and her husband would also buy land there and in the adjacent communities of Playa del Carmen and Cozumel, believing that one day the area would grow and attract tourists. In the meantime, their hotel chain spread throughout Mexico, offering 4-star accommodations in places as diverse as Ciudad Juárez and Acapulco. With expert builders and contractors at the ready, Yolanda Vargas Dulché and her husband Guillermo decided to build a huge hacienda as a personal retreat. By 1985, the couple finished work on La Hacienda Mortero outside the town of Súchil in the Mexican state of Durango. As with every enterprise under her control, Vargas turned the retreat into a moneymaking venture. The hacienda produces to this day thousands of pounds of pecans from groves of trees across many acres. The raw nuts and finished products are exported all over the world. Some of the proceeds of this little side venture have gone to funding schools, hospitals and housing throughout the poorer parts of the state of Durango.

Incredibly, during the time of the most phenomenal growth of their various businesses, Yolanda and Guillermo were also raising 5 children. Their five children all became successful adults, and some of their children – Vargas’ grandchildren – have also gone on to live fruitful lives. A notable granddaughter, for example, Alondra de la Parra, is an accomplished musician and composer. She currently serves as the Musical Director of the Queensland Symphony Orchestra, the first ever female principal conductor of an Australian symphony orchestra. In addition to her many accomplishments in the worlds of the arts and business, Yolanda Vargas Dulché also managed to create and incredible home life and family.

Incredibly, during the time of the most phenomenal growth of their various businesses, Yolanda and Guillermo were also raising 5 children. Their five children all became successful adults, and some of their children – Vargas’ grandchildren – have also gone on to live fruitful lives. A notable granddaughter, for example, Alondra de la Parra, is an accomplished musician and composer. She currently serves as the Musical Director of the Queensland Symphony Orchestra, the first ever female principal conductor of an Australian symphony orchestra. In addition to her many accomplishments in the worlds of the arts and business, Yolanda Vargas Dulché also managed to create and incredible home life and family.

Sadly, many people in the United States, especially Mexican Americans, have never heard of Yolanda Vargas Dulché. At the time of her death in 1999 Vargas was one of the wealthiest Mexican women who ever lived. She influenced the popular culture of Mexico to a degree that has no equal among men or women. Her incredible mind enriched the lives of millions of people and in the end, she left Mexico a more magical place.

REFERENCES

Mexico’s Museo de Arte Popular web site (in Spanish) http://www.amigosmap.org.mx/2012/11/26/biografia-de-yolanda-vargas-dulche/

A great exploration of the art behind the comics in Mexico can be found here: https://amzn.to/2L9DqDl