Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

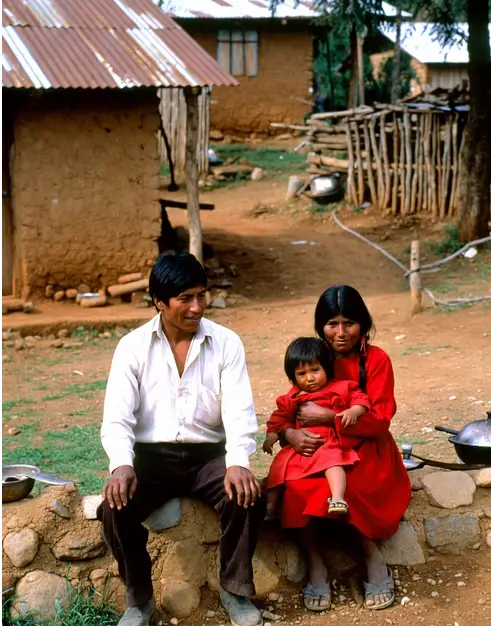

The Cora people, known to themselves as Náayerite in plural or Náayeri in singular, are an indigenous ethnic group deeply rooted in the rugged landscapes of western Mexico. Primarily inhabiting the Sierra Madre mountains and canyons in the state of Nayarit, with extensions into neighboring Durango, Jalisco, and Sinaloa, they have maintained a resilient cultural identity amidst centuries of external pressures. Their population, as recorded in early 21st-century censuses, hovers around 30,000 to 40,000 individuals. This number includes those who speak the Cora language and those who do not. The Cora’s homeland is characterized by steep hillsides, dry climates, and isolated communities, which have both protected and challenged their way of life. This episode of Mexico Unexplained explores their journey from ancient origins through historical upheavals to the modern era, highlighting their enduring traditions and the obstacles they face today.

The Cora people, known to themselves as Náayerite in plural or Náayeri in singular, are an indigenous ethnic group deeply rooted in the rugged landscapes of western Mexico. Primarily inhabiting the Sierra Madre mountains and canyons in the state of Nayarit, with extensions into neighboring Durango, Jalisco, and Sinaloa, they have maintained a resilient cultural identity amidst centuries of external pressures. Their population, as recorded in early 21st-century censuses, hovers around 30,000 to 40,000 individuals. This number includes those who speak the Cora language and those who do not. The Cora’s homeland is characterized by steep hillsides, dry climates, and isolated communities, which have both protected and challenged their way of life. This episode of Mexico Unexplained explores their journey from ancient origins through historical upheavals to the modern era, highlighting their enduring traditions and the obstacles they face today.

The ancient history of the Cora traces back to pre-Columbian times, when they were part of the broader Uto-Aztecan linguistic and cultural family that spanned much of northern and western Mexico. Linguistic evidence suggests connections to groups like the Tepehuanes, Huicholes, Pimas, Tarahumaras, and Yaquis, with shared roots in migratory patterns from the north. Archaeological findings indicate that the Cora developed sophisticated agricultural techniques suited to their mountainous terrain. They constructed terraces on steep slopes to prevent soil erosion, cultivating staple crops such as maize, beans, squash, amaranth, and cucumbers. This innovation allowed them to thrive in an otherwise unforgiving environment, where rainfall was seasonal and resources scarce. Hunting, fishing, and gathering wild foods supplemented their diet, including deer, rabbits, fish from rivers, and edible plants like agave and wild berries.

Socially, ancient Cora society was organized around extended family units and loose clusters of households known by their later Spanish name – rancherías – rather than large centralized villages. These dispersed settlements, typically consisting of one to a dozen homes, fostered a sense of communal interdependence while allowing flexibility in the rugged landscape. Leadership was often vested in religious figures, such as priests or shamans who mediated between the human world and the divine. Their belief system was animistic, revering natural elements like the sun, moon, rain,  and maize as deities. The supreme sun god, Tayau or “Our Father,” was central, depicted as traversing the sky and resting on a golden throne at noon, with clouds interpreted as smoke from his pipe. His wife, Tetewan or the moon goddess, governed the underworld, rain, and the western direction, while their son Sautari embodied maize and the afternoon, symbolizing growth and sustenance. Myths of creation, including the formation of the fifth sun and a great deluge where humanity descended from a man and a dog-woman survivor, echoed broader Mesoamerican narratives, suggesting cultural exchanges with distant civilizations like the Aztecs.

and maize as deities. The supreme sun god, Tayau or “Our Father,” was central, depicted as traversing the sky and resting on a golden throne at noon, with clouds interpreted as smoke from his pipe. His wife, Tetewan or the moon goddess, governed the underworld, rain, and the western direction, while their son Sautari embodied maize and the afternoon, symbolizing growth and sustenance. Myths of creation, including the formation of the fifth sun and a great deluge where humanity descended from a man and a dog-woman survivor, echoed broader Mesoamerican narratives, suggesting cultural exchanges with distant civilizations like the Aztecs.

Rituals played a pivotal role in ancient Cora life, reinforcing social bonds and ensuring harmony with nature. Peyote, a hallucinogenic cactus described in Mexico Unexplained episode number 49 https://youtu.be/kZvO-NUXCRA , was used in certain ceremonies to induce visions and connect with the spiritual realm. Artisans crafted simple pottery for daily use, wove sashes, bags, and blankets on backstrap looms, and created embroidered items and jewelry. Men typically wore muslin shirts, pants, sandals, and hats, sometimes adorned with sashes and shoulder bags; women donned long skirts, blouses, sandals, and capes known as quechquemitl. These practices not only met practical needs but also expressed cultural identity, with designs often incorporating symbolic motifs from their religious worldview.

The arrival of Europeans marked a turning point in Cora history. First contact occurred in 1524 when Spanish captain Francisco Cortés de San Buenaventura reached what is now Tepic, receiving gifts from local warriors. However, the brutal expedition of Nuño de Guzmán in 1530 unleashed atrocities, including the burning alive of a Cora governor and the slaughter of children, igniting widespread resistance. The Mixtón Rebellion described in Mexico Unexplained episode number 88 https://youtu.be/ZelnVjxcJJw erupted in 1540, uniting indigenous groups across southern Nayarit, Jalisco, and Zacatecas in a fierce uprising against Spanish encroachment. Lasting until 1542, it was ultimately quelled by superior Spanish forces, but it demonstrated the Cora’s warrior spirit. The challenging terrain of the Sierra Madre delayed full conquest for decades. In 1592, Captain Miguel Caldera attempted diplomacy, but rebellions persisted, including a joint effort with Tarahumaras and Tepehuanes from 1616 to 1618.

By the early 1700s, the Cora remained a “pagan island” in a sea of Christianized natives, having expelled or resisted Catholic missionaries. A 1716 Spanish expedition failed, but in 1721, Cora chief Tonati negotiated terms for submission, including land rights and self-governance. Betrayal followed, with Spanish forces under Viceroy Baltasar de Zuniga seizing Mesa del Nayar in 1722, confining the Cora to Jesuit-controlled villages by 1723. Drought, epidemics, and famine had weakened them, facilitating subjugation. The Jesuits established missions, but their expulsion in by the Spanish king 1767 led to intermittent Catholic influence, allowing the Cora to blend Christianity with their traditional indigenous beliefs in a unique syncretism.

By the early 1700s, the Cora remained a “pagan island” in a sea of Christianized natives, having expelled or resisted Catholic missionaries. A 1716 Spanish expedition failed, but in 1721, Cora chief Tonati negotiated terms for submission, including land rights and self-governance. Betrayal followed, with Spanish forces under Viceroy Baltasar de Zuniga seizing Mesa del Nayar in 1722, confining the Cora to Jesuit-controlled villages by 1723. Drought, epidemics, and famine had weakened them, facilitating subjugation. The Jesuits established missions, but their expulsion in by the Spanish king 1767 led to intermittent Catholic influence, allowing the Cora to blend Christianity with their traditional indigenous beliefs in a unique syncretism.

During the colonial period, the Cora were integrated into the Spanish empire as laborers in mines and haciendas, though many retreated to remote areas to preserve their autonomy. They adopted elements of Catholicism, such as patron saints, but reinterpreted them as native gods. Communities were reorganized into what was termed formally as “indigenous communities,” colonial land grants that evolved into modern ejidos, which are communal agricultural lands. Despite oppression, the Cora maintained core traditions, including their language with eight dialects—Rosarito, Dolores, Meseño, Jesús María, Francisqueño, Tereseño, Presideño, and Corapeño—reflecting regional variations. Bilingualism in Spanish emerged, but Cora remained the primary tongue in isolated rancherías.

The 1800s brought new turmoil with Mexico’s independence in 1821. The Cora joined independence movements, hoping for land reforms, but faced continued seizures by mestizos and Spaniards. In 1857, under native leader Manuel Lozada, they participated in a peasant rebellion commanding thousands, including Cora and Huichol fighters, occupying vast territories. Lozada, executed in 1873, is remembered as a precursor to agrarian reform. Nayarit, named after the legendary Cora warrior who founded the Kingdom of Xécora, became a state in 1917 after periods as a military district and territory.

In the post-independence era, the Cora navigated modernization while clinging to traditions. Their economy remained subsistence-based, with families keeping cows for milk and cheese, sheep for wool, and other animals, though meat consumption was minimal. Crafts like pottery, weaving, and embroidery persisted, as did ritual kinship, where godparents were chosen at key life events to strengthen social ties. Religion evolved into a hybrid: nominally Roman Catholic, with ceremonies centering on traditional native elements. Peyote rites continued, and myths intertwined Christian figures like Jesus with indigenous deities like Sautari. One of the most vivid expressions of this syncretism is the Holy Week celebration, known as Judea, in villages like Santa Teresa. This week-long event, devoid of priestly oversight, reenacts Christ’s passion through indigenous lenses as a battle between good and evil. It begins on Wednesday with men marking village boundaries to “close the glory.” Men and boys paint themselves black and white, transforming into what they call “The Erased Ones,” engaging in mock battles. Women decorate eggs and participate in symbolic rituals. Processions carry wooden saints on carts, accompanied by copal incense, drums, flutes, and Roman centurions on horseback. The climax on Good Friday involves “destroying” the church altar, symbolizing crucifixion, followed by intense combats. By Saturday, exhaustion leads to resolution, blending Catholic resurrection with pre-Hispanic themes of metamorphosis, nature worship, and communal renewal.

In modern times, the Cora face a blend of preservation and peril. In Mexico, they reside in municipios like El Nayar, where over 80% are indigenous, sustaining agriculture and crafts. However, declining language speakers—from nearly half in 1990 to well under 40% in 2010—signal cultural erosion, with high monolingualism among elders. Violence from drug cartels, tied to marijuana cultivation in Nayarit, has disrupted communities, prompting migration. Since the 1990s, many Cora, especially youth, have fled to the United States for economic opportunities and safety. Initial waves worked in sheep herding and construction, settling in states like Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Gunnison, Colorado, hosts the largest diaspora, around 350 individuals, drawn by mountainous familiarity and established networks. Here, they form tight-knit communities, preserving dialects and traditions, but face integration challenges.

In modern times, the Cora face a blend of preservation and peril. In Mexico, they reside in municipios like El Nayar, where over 80% are indigenous, sustaining agriculture and crafts. However, declining language speakers—from nearly half in 1990 to well under 40% in 2010—signal cultural erosion, with high monolingualism among elders. Violence from drug cartels, tied to marijuana cultivation in Nayarit, has disrupted communities, prompting migration. Since the 1990s, many Cora, especially youth, have fled to the United States for economic opportunities and safety. Initial waves worked in sheep herding and construction, settling in states like Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Gunnison, Colorado, hosts the largest diaspora, around 350 individuals, drawn by mountainous familiarity and established networks. Here, they form tight-knit communities, preserving dialects and traditions, but face integration challenges.

Contemporary challenges for the Cora people are multifaceted. In Mexico, land rights disputes, access to education, and healthcare persist, exacerbated by isolation. Cartel violence has led to family separations and trauma. In the U.S., language barriers hinder services; Cora dialects differ from Spanish, causing delays in medical care and reluctance to seek help. Health beliefs integrate Western medicine with indigenous practices—curanderos for spiritual ailments, herbalists, bone-setters, and masseurs—creating clashes with U.S. systems. Mental health stigma, rooted in views of it as weakness, compounds issues from migration trauma, depression, and cultural disconnection. Efforts to address these include community advocacy. In Gunnison, translators assist in courts, hospitals, and social services. Hospitals explore cultural competency training, telehealth links to Mexican healers, and training local doulas or midwives. In Mexico, autonomous communities like Jesús María maintain self-sufficiency, with hospitals offering dual Western and indigenous wings. Elders worry about youth migration eroding traditions, as younger generations adopt urban ways, potentially diluting rituals and language. Despite these hurdles, the Cora’s resilience shines. Their history of resistance—from ancient warriors to modern migrants—underscores a people adaptable yet steadfast. As they navigate globalization, preserving their náayeri identity amid mountains and migrations remains their greatest endeavor. In blending ancient wisdom with contemporary realities, the Cora continue to embody the spirit of the Sierra Madre, a testament to indigenous endurance in a changing world.

REFERENCES