Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Mexico Unexplained must return once again to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived at the magnificent city they were not met with hostility. The emperor knew Cortés was coming, and curious about the Spaniard’s intentions, he welcomed the visitor and his men as honored guests. Because of this cordial reception many first-hand European accounts exist of a living and breathing Aztec Empire. All of Cortés’ contingent was amazed at the city. The massive imperial palace complex drew much attention. There were swimming pools, lavish apartments for the emperor’s family and foreign dignitaries, lush gardens where thousands of flowers bloomed and the often-wrote-about legendary private zoo of Montezuma, explored in depth in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 43. https://mexicounexplained.com/montezumas-zoo/ The zoo was said to rival that of the Great Khan in China and contained animals from throughout the Aztec Empire and beyond. In the section devoted to beasts of prey, the Spanish were amazed to view what they called an oso plateado, or in English, “silvery bear,” better known by its scientific name Ursus arctos horribilis or more commonly, the Mexican Grizzly Bear.

Mexico Unexplained must return once again to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived at the magnificent city they were not met with hostility. The emperor knew Cortés was coming, and curious about the Spaniard’s intentions, he welcomed the visitor and his men as honored guests. Because of this cordial reception many first-hand European accounts exist of a living and breathing Aztec Empire. All of Cortés’ contingent was amazed at the city. The massive imperial palace complex drew much attention. There were swimming pools, lavish apartments for the emperor’s family and foreign dignitaries, lush gardens where thousands of flowers bloomed and the often-wrote-about legendary private zoo of Montezuma, explored in depth in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 43. https://mexicounexplained.com/montezumas-zoo/ The zoo was said to rival that of the Great Khan in China and contained animals from throughout the Aztec Empire and beyond. In the section devoted to beasts of prey, the Spanish were amazed to view what they called an oso plateado, or in English, “silvery bear,” better known by its scientific name Ursus arctos horribilis or more commonly, the Mexican Grizzly Bear.

The Aztecs called this gigantic creature a pissini, and that name came from the Opata language, spoken by the people with the same name, who lived and still live in what is now the northern Mexican state of Sonora. The Aztec Empire did not include the Opatería, or the homeland of the Opatas, so Emperor Montezuma’s zoo acquisition most likely occurred through long-distance trade, much as he acquired a buffalo, or North American bison. One can only imagine how difficult it must have been for the ancients to trap a grizzly and transport it over hundreds of miles without wheeled vehicles and without a way to sedate the bear. The Spanish first encountered the Mexican grizzly in the wild during the Coronado Expedition of 1540, just 21 years after Cortés and his group of conquistadors saw their first one in captivity in Montezuma’s Zoo. Coronado’s people most likely saw their first Mexican grizzly as they passed north through the Sierra Madre of Chihuahua on their way to New Mexico while searching for the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. For more on the Coronado Expedition and this legend, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 27 https://mexicounexplained.com/seven-cities-gold/

So, what was this bear like? The Mexican grizzly bear was a type of brown bear and was one of the largest known mammals in Mexico. It could stand 6 feet tall and could weigh up to 700 pounds, which made it a little smaller than its North American cousins in the US and Canada. It got the name oso plateado, or “silvery bear” because many of these bears have silver tints or silver undertones in their fur. Generally, though, the Mexican grizzly had a golden to dark brown appearance with darker underfur. The bear’s habitat was restricted to the mountains and grasslands of the northern states of Mexico: Chihuahua, Sonora, Coahuila, Durango and Baja California. The Mexican grizzly was an omnivore, so it ate both plants and animals. Its diet was comprised mostly of fruits and insects, and the bear had a particular fondness for ants. It ate small animals such as squirrels and would fish in rivers and lakes. Especially hungry bears would often kill livestock as large as cows, but generally the bears stayed away from human settlements. The Mexican grizzly had very little competition from other animals in the wild. Sometimes coyotes would eat the smaller mammals in the bears’ territory, but the grizzly could always make up for the lack of animals in its diet by eating plants. The Mexican grizzly didn’t hibernate, but restricted its winter activity, spending most of the time in the colder months in dens. The bears lived to be about 25 years old and female grizzlies would bear young once every three years or so.

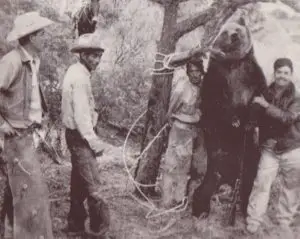

As ranchers and hacienda owners pushed into the northern territories of Mexico starting in the late 1600s, human and bear confrontations became more frequent. The ranchers and hacendados claimed that the Mexican grizzlies were killing their livestock, and sometimes whole villages would go on hunts to track down and kill renegade bears. By the late 1800s there were few grizzlies left in the wild, and they became sought after by American trophy hunters. The last documented Mexican grizzly in Baja was killed in 1899. By the 1930s there were said to be only a few dozen of the bears left, all of them living in three isolated mountain ranges in north-central Chihuahua, the Cerro Campana, Cerro Santa Clara, and Sierra del Nido. Although technically protected, the bears were still being trapped, shot, and poisoned well into the 1950s. By the mid-1960s wildlife officials in Mexico proclaimed the Mexican grizzly extinct. Rumors of the bears’ continued existence persisted, however, and in 1968 American biologist Dr. Carl Buckingham Koford went on a 49-day expedition into the Sierra del Nido looking for the elusive creatures. He found no bears, nor did he find any signs of them. In the spring and fall of 1974, Aubrey Stephen Johnson, the Southwest Representative of an American organization called the Defenders of Wildlife, also surveyed the Sierra del Nido area. Johnson searched for 6 weeks but found no evidence of grizzly bears. Perhaps Koford and Johnson were looking in the wrong place. In 1976, a rancher in Sonora shot a Mexican grizzly in a place aptly named: Arroyo el Oso, or in English, “Bear Stream” located about 50 miles south of the US-Mexico border outside the town of Ímuris. The habitat was mixed pine and oak woodland, and the bear was shot while feeding on a mountain lion kill. This location is a few hundred miles west of the Sierra del Nido in Chihuahua where much of the attention on rediscovering the bear had been focused. Although rumors of this

As ranchers and hacienda owners pushed into the northern territories of Mexico starting in the late 1600s, human and bear confrontations became more frequent. The ranchers and hacendados claimed that the Mexican grizzlies were killing their livestock, and sometimes whole villages would go on hunts to track down and kill renegade bears. By the late 1800s there were few grizzlies left in the wild, and they became sought after by American trophy hunters. The last documented Mexican grizzly in Baja was killed in 1899. By the 1930s there were said to be only a few dozen of the bears left, all of them living in three isolated mountain ranges in north-central Chihuahua, the Cerro Campana, Cerro Santa Clara, and Sierra del Nido. Although technically protected, the bears were still being trapped, shot, and poisoned well into the 1950s. By the mid-1960s wildlife officials in Mexico proclaimed the Mexican grizzly extinct. Rumors of the bears’ continued existence persisted, however, and in 1968 American biologist Dr. Carl Buckingham Koford went on a 49-day expedition into the Sierra del Nido looking for the elusive creatures. He found no bears, nor did he find any signs of them. In the spring and fall of 1974, Aubrey Stephen Johnson, the Southwest Representative of an American organization called the Defenders of Wildlife, also surveyed the Sierra del Nido area. Johnson searched for 6 weeks but found no evidence of grizzly bears. Perhaps Koford and Johnson were looking in the wrong place. In 1976, a rancher in Sonora shot a Mexican grizzly in a place aptly named: Arroyo el Oso, or in English, “Bear Stream” located about 50 miles south of the US-Mexico border outside the town of Ímuris. The habitat was mixed pine and oak woodland, and the bear was shot while feeding on a mountain lion kill. This location is a few hundred miles west of the Sierra del Nido in Chihuahua where much of the attention on rediscovering the bear had been focused. Although rumors of this  1976 bear shooting existed throughout the years the skull of the bear was only researched in the year 2005. Investigators concluded that the bear was young which may have indicated that its parents and/or siblings could have also been alive in the mid-1970s. If the bear had siblings, biologists believe, there could have been Mexican grizzlies living in the area at least through the mid-1980s if not into the early 1990s. No one followed up on the rumor of the 1976 shooting at the time, so researchers were still focused on the Sierra del Nido area just 50 or so miles north of the City of Chihuahua, the dense wilderness where the last handful of bears was spotted in the 1950s. So, in May of 1979, as part of a cooperative agreement between the US and Mexican governments to investigate the status of the Mexican grizzly bears, the University of Montana Border Grizzly Project conducted an extensive on-site investigation and live trapping program. The project spent 51 days on the eastern slopes of the Sierra del Nido. One of the snares was disturbed by what appeared to be a small bear, and that animal left behind tracks. The researchers on this expedition not only found claw marks on trees, and fur beside scratching poles, they saw two bears in the distance through binoculars. When they went to the location of their sighting they found no paw prints, claw marks or any tangible evidence of what they saw, but this visual evidence proved to them that the bears still existed. Charles Jonkel of the University of Montana’s School of Forestry, and his Mexican counterpart José Trevino, the Director of Forest Fauna for the State of Chihuahua, published a paper in 1980 summarizing their findings from the May 1979 expedition to find the bears. The two wrote this as part of the paper’s concluding remarks:

1976 bear shooting existed throughout the years the skull of the bear was only researched in the year 2005. Investigators concluded that the bear was young which may have indicated that its parents and/or siblings could have also been alive in the mid-1970s. If the bear had siblings, biologists believe, there could have been Mexican grizzlies living in the area at least through the mid-1980s if not into the early 1990s. No one followed up on the rumor of the 1976 shooting at the time, so researchers were still focused on the Sierra del Nido area just 50 or so miles north of the City of Chihuahua, the dense wilderness where the last handful of bears was spotted in the 1950s. So, in May of 1979, as part of a cooperative agreement between the US and Mexican governments to investigate the status of the Mexican grizzly bears, the University of Montana Border Grizzly Project conducted an extensive on-site investigation and live trapping program. The project spent 51 days on the eastern slopes of the Sierra del Nido. One of the snares was disturbed by what appeared to be a small bear, and that animal left behind tracks. The researchers on this expedition not only found claw marks on trees, and fur beside scratching poles, they saw two bears in the distance through binoculars. When they went to the location of their sighting they found no paw prints, claw marks or any tangible evidence of what they saw, but this visual evidence proved to them that the bears still existed. Charles Jonkel of the University of Montana’s School of Forestry, and his Mexican counterpart José Trevino, the Director of Forest Fauna for the State of Chihuahua, published a paper in 1980 summarizing their findings from the May 1979 expedition to find the bears. The two wrote this as part of the paper’s concluding remarks:

“We concur that grizzly bears may still exist in Mexico. We base our conclusions on the following key points:

1. Brown bear populations elsewhere demonstrate a special ability to remain viable even though isolated and at low population levels.

2. The longevity of grizzly bears (20-25 years in the wild) and the relatively recent records of grizzly bears in Mexico means that a few survivors could still exist, even if a viable population is not present.

3. Because of their remarkable ability to use cover, grizzly bears could survive without being detected.

4. Several likely areas for grizzly bears in Mexico have not been studied.

5. Grizzly bear habitat is adequate and abundant in Mexico.”

Despite the research done by the Border Grizzly Project, just two years after their findings were published, the IUCN – The International Union for Conservation of Nature – released a paper declaring that the Mexican grizzly bear is extinct. Since this second declaration of extinction there have been many alleged sightings or rumors of sightings of these animals in the remote mountains of Sonora and Chihuahua. In December of 2019, wildlife biologist Forrest Galante from Animal Planet’s “Extinct or Alive” appeared on the Joe Rogan Experience Podcast (episode #1403) talking about the Mexican grizzly: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCRjz1fyOE4&t=0s Galante said that it was possible that small groups of bears may still live in what biologists call “sky islands” of isolated habitats in the high sierras of northern Mexico. The possible existence of this extinct bear is so strange, Galante stated, that researchers are just not interested in pursuing this.

Despite the research done by the Border Grizzly Project, just two years after their findings were published, the IUCN – The International Union for Conservation of Nature – released a paper declaring that the Mexican grizzly bear is extinct. Since this second declaration of extinction there have been many alleged sightings or rumors of sightings of these animals in the remote mountains of Sonora and Chihuahua. In December of 2019, wildlife biologist Forrest Galante from Animal Planet’s “Extinct or Alive” appeared on the Joe Rogan Experience Podcast (episode #1403) talking about the Mexican grizzly: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCRjz1fyOE4&t=0s Galante said that it was possible that small groups of bears may still live in what biologists call “sky islands” of isolated habitats in the high sierras of northern Mexico. The possible existence of this extinct bear is so strange, Galante stated, that researchers are just not interested in pursuing this.

So, was that poor young bear shot in Sonora in 1976 the last Mexican grizzly bear? Maybe so, maybe not.

REFERENCES

4 thoughts on “The Last Mexican Grizzly Bear”

Hello,

Love your podcasts but some of them skip a lot. Is it an error on my browser or phone or is there a place to get them that they don’t skip? Thanks!

Steffanyaguilar2020@gmail.com

Hi Steffany and thanks for commenting. I have been hearing this for years and years from people. Some people have this problem and others don’t. I have tried testing this out myself and I never have the problem. I wish I could know what is going on and fix it, if I could. I really don’t know what to do. I know that no one has brought this up with YouTube, so I suggest you go there instead of trying to listen to it in the podcast format. Again, thanks for reaching out and thank you doubly for liking my work. Take care. —Robert

I want to know more about this beast. I am very curious to know about its cultural reverence in native mexico

The Montana Border Grizzly Project saw two bears from a distance in the Sierra del Nido mountains. There are black bears in that range as I have spent weeks there, I have seen four of them. A young one had an odd color/pattern that was dark and very light. I called it a Mexican Panda Bear. It came right up to my car early in the evening but I shined a flashlight on it. I also photographed a small bear skull and other bones with it in those mountains.