Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés bowed before the Spanish King Charles the Fifth in his first formal reception in Spain since his conquest of the Aztecs. The year was 1528. Cortés went to the Spanish court at Madrid not only to receive his titles of nobility from his king but to plead his case to continue governing the new territories of the Spanish Empire in Mexico. In the aftermath of the brutal destruction of the Aztec Empire many had questioned Cortés’ tactics and motives and the conquistador knew he had to appear before King Charles to remove all doubt about his loyalty to the Crown. He wanted also to reassure his king that he indeed was sending more than the required royal fifth, or quinto, of all the riches discovered in the new territories he conquered. Part of Cortés’ plan to ingratiate himself was to put on a pageant at the Spanish Court to showcase the marvels of the New World. Cortés had quite a show planned, full of exotic animals and a show of Native Indian talents and abilities. Part of this show was a demonstration of the ballgame played throughout Mexico at the time of the Conquest. The large hall in the royal palace filled with gasps of amazement when the Aztec ball players got on with their demonstration. The players, clad in full ball game regalia, bounced the rubber ball off their hips and the palace floor so rapidly and with so much prowess that it caused great delight among the crowd of nobles, visiting dignitaries and members of the clergy. The Spanish king’s beautiful wife, the 25-year-old Queen Isabella of Portugal, laughed along with her ladies in waiting for they had never seen something so unusual as the bouncing rubber ball. The members of the Catholic Church present were not so amused. The dour-faced clergymen had heard that the rubber balls used in this game often had human skulls in their centers. The game would have to be examined under the rules of the Spanish Inquisition and as with all pagan practices of the New World, the ballgame would most likely have to be abolished. The members of the priestly class in attendance at the Cortés event held their tongues and let the nobles have their momentary enjoyment.

Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés bowed before the Spanish King Charles the Fifth in his first formal reception in Spain since his conquest of the Aztecs. The year was 1528. Cortés went to the Spanish court at Madrid not only to receive his titles of nobility from his king but to plead his case to continue governing the new territories of the Spanish Empire in Mexico. In the aftermath of the brutal destruction of the Aztec Empire many had questioned Cortés’ tactics and motives and the conquistador knew he had to appear before King Charles to remove all doubt about his loyalty to the Crown. He wanted also to reassure his king that he indeed was sending more than the required royal fifth, or quinto, of all the riches discovered in the new territories he conquered. Part of Cortés’ plan to ingratiate himself was to put on a pageant at the Spanish Court to showcase the marvels of the New World. Cortés had quite a show planned, full of exotic animals and a show of Native Indian talents and abilities. Part of this show was a demonstration of the ballgame played throughout Mexico at the time of the Conquest. The large hall in the royal palace filled with gasps of amazement when the Aztec ball players got on with their demonstration. The players, clad in full ball game regalia, bounced the rubber ball off their hips and the palace floor so rapidly and with so much prowess that it caused great delight among the crowd of nobles, visiting dignitaries and members of the clergy. The Spanish king’s beautiful wife, the 25-year-old Queen Isabella of Portugal, laughed along with her ladies in waiting for they had never seen something so unusual as the bouncing rubber ball. The members of the Catholic Church present were not so amused. The dour-faced clergymen had heard that the rubber balls used in this game often had human skulls in their centers. The game would have to be examined under the rules of the Spanish Inquisition and as with all pagan practices of the New World, the ballgame would most likely have to be abolished. The members of the priestly class in attendance at the Cortés event held their tongues and let the nobles have their momentary enjoyment.

The Aztecs called it ollamaliztli, to the Maya, it was pitz. The Spanish conquerors called it juego de pelota. In English we refer to it as the Mesoamerican ballgame. This game, in various forms, dates back to around 1600 BC and is recognized as the first team sport ever played on earth. It originated among the Olmec people in the lowland jungle forest areas of Mexico where rubber for the balls was cultivated from the sap of a tree. The game spread from this area all the way south to Nicaragua and as far north, through trade, to the Hohokam civilization in the area of modern-day Phoenix, Arizona, which played it from about 600 AD to 1200 AD. Over 1,300 ancient ball courts have been uncovered spanning the geographical area previously mentioned. Every culture in ancient Mexico played the ballgame, except for the ancient city-state of Teotihuacán. Although depicted on murals at the city, no ball courts have been found at Teotihuacán or in those cities that fell under its sphere of control. The playing of the game was largely snuffed out by the Spanish, who regarded it as a pagan practice, with some forms of the game surviving in the rural areas of the state of Sinaloa where a ballgame similar to that of the ancients called ulama is still played to this day.

The Aztecs called it ollamaliztli, to the Maya, it was pitz. The Spanish conquerors called it juego de pelota. In English we refer to it as the Mesoamerican ballgame. This game, in various forms, dates back to around 1600 BC and is recognized as the first team sport ever played on earth. It originated among the Olmec people in the lowland jungle forest areas of Mexico where rubber for the balls was cultivated from the sap of a tree. The game spread from this area all the way south to Nicaragua and as far north, through trade, to the Hohokam civilization in the area of modern-day Phoenix, Arizona, which played it from about 600 AD to 1200 AD. Over 1,300 ancient ball courts have been uncovered spanning the geographical area previously mentioned. Every culture in ancient Mexico played the ballgame, except for the ancient city-state of Teotihuacán. Although depicted on murals at the city, no ball courts have been found at Teotihuacán or in those cities that fell under its sphere of control. The playing of the game was largely snuffed out by the Spanish, who regarded it as a pagan practice, with some forms of the game surviving in the rural areas of the state of Sinaloa where a ballgame similar to that of the ancients called ulama is still played to this day.

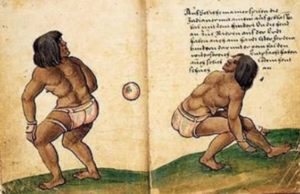

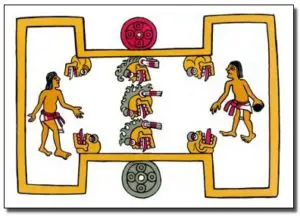

Although the Spanish came into contact with the living Aztec Empire which played the ballgame at the time of the Conquest, little is known about the rules of the game, and there were most likely different types of games using the ubiquitous rubber ball across time and across cultures. Archeologists have discovered different sizes of balls which would indicate different types of games. From what the Spanish observed of the Aztecs, the game was played by teams of 2 to 4 people on a masonry court called a tlachtli that was in the shape of the letter I. The ball was hit to the other team and points were deducted if the ball bounced on the ground more than twice. Points were also lost if the ball went out of bounds or if an attempt was made to pass the ball through the stone ring which was midway in the court and about 6 feet above the ground. A ball passing through the ring was an instant win. Although the Spanish were keen on chronicling everything in their newly conquered domains, they seemed not to be very interested in the meaning of the game or saw it as unimportant. As noted before with the demonstration for the king of Spain, the ball itself seemed to garner the most attention because its properties were so unusual. According to the Franciscan missionary, Toribio de Benevente, “The balls of this land are very heavy. The Indians run and jump so much that it as if the balls have quicksilver.” Besides noting the severe injuries ball players suffered from being hit by the quick flying rubber balls, there is very little more about this game from firsthand Spanish observers. Most of what we know today about the Mesoamerican ballgame comes from the archaeological record.

Although the Spanish came into contact with the living Aztec Empire which played the ballgame at the time of the Conquest, little is known about the rules of the game, and there were most likely different types of games using the ubiquitous rubber ball across time and across cultures. Archeologists have discovered different sizes of balls which would indicate different types of games. From what the Spanish observed of the Aztecs, the game was played by teams of 2 to 4 people on a masonry court called a tlachtli that was in the shape of the letter I. The ball was hit to the other team and points were deducted if the ball bounced on the ground more than twice. Points were also lost if the ball went out of bounds or if an attempt was made to pass the ball through the stone ring which was midway in the court and about 6 feet above the ground. A ball passing through the ring was an instant win. Although the Spanish were keen on chronicling everything in their newly conquered domains, they seemed not to be very interested in the meaning of the game or saw it as unimportant. As noted before with the demonstration for the king of Spain, the ball itself seemed to garner the most attention because its properties were so unusual. According to the Franciscan missionary, Toribio de Benevente, “The balls of this land are very heavy. The Indians run and jump so much that it as if the balls have quicksilver.” Besides noting the severe injuries ball players suffered from being hit by the quick flying rubber balls, there is very little more about this game from firsthand Spanish observers. Most of what we know today about the Mesoamerican ballgame comes from the archaeological record.

What are found in most abundance in the archaeological record are the rubber balls. They were hollow or solid, and sometimes were comprised of a human skull covered in strips of rubber. Each ball weighed between 6 and 10 pounds. The rubber was made from the sap of the rubber tree and was mixed with the juice of a type of morning glory to give the ball extra bounce. The surfaces of the balls were always without decoration and were mostly smooth.

What are found in most abundance in the archaeological record are the rubber balls. They were hollow or solid, and sometimes were comprised of a human skull covered in strips of rubber. Each ball weighed between 6 and 10 pounds. The rubber was made from the sap of the rubber tree and was mixed with the juice of a type of morning glory to give the ball extra bounce. The surfaces of the balls were always without decoration and were mostly smooth.

The most obvious structural remnant of the ballgame found in the ancient Mexican archaeological sites is the ball court. The court could be of varying sizes but it always had the same shape. From above, it looked like the letter I with a playing alley and two end zones. On either side of the playing alley were gently sloping brick or cement walls. On the  walls in the later phases of Classic culture there also appeared a large stone ring through which the rubber ball was passed. The masonry walls of the playing alley sloped down to a bench-like structure that was flat and about two feet tall. On these two-foot tall miniature walls we find illustrations and relief sculptures that give us some clues as to what happened in connection to the game. These sculptures show the ball players, the priests and nobles and often sacrificial victims with their hearts being torn out or with decapitated torsos. It is surmised that many times the members of the losing teams were sacrificed but not always. Some theorize that the ball games could have been used instead of wars to settle disputes among rival political entities. Spectators stood at the tops of the walls of the playing alleys. Ball games were a family affair. Clay dioramas of ball courts have been discovered showing parents with children attending the games. In addition to the prized spots on top of the court walls, many spectators could witness the games from adjacent buildings that were higher than the ball courts which averaged between two to five meters high.

walls in the later phases of Classic culture there also appeared a large stone ring through which the rubber ball was passed. The masonry walls of the playing alley sloped down to a bench-like structure that was flat and about two feet tall. On these two-foot tall miniature walls we find illustrations and relief sculptures that give us some clues as to what happened in connection to the game. These sculptures show the ball players, the priests and nobles and often sacrificial victims with their hearts being torn out or with decapitated torsos. It is surmised that many times the members of the losing teams were sacrificed but not always. Some theorize that the ball games could have been used instead of wars to settle disputes among rival political entities. Spectators stood at the tops of the walls of the playing alleys. Ball games were a family affair. Clay dioramas of ball courts have been discovered showing parents with children attending the games. In addition to the prized spots on top of the court walls, many spectators could witness the games from adjacent buildings that were higher than the ball courts which averaged between two to five meters high.

Unearthed figurines, murals and other illustrations give us insight into the uniforms worn by ball game players and some of the equipment used. Players wore what are called yuquitos, leather or cloth pads which may have been used to protect the wrists, knees or shins. They were often decorated with a skull or human face. They would also wear a yoke around the waist that was almost like a girdle. This was made of heavy fabric, leather or wicker wood and may have also been used as protection against the fast-moving ball. Carved stone yokes were used ceremoniously before and after the ball games in place of the fabric, leather or wicker ones. The stone yokes are the only types that have survived and they are often elaborately decorated and inlaid with semi-precious stones. An hacha was a carved stone decoration in a shape of a hatchet blade that was attached to the yoke and was personalized to the player. Another stone accessory was a palma which was either held in place in the hand or attached to the yoke. Many times the palma was carved in the shape of maize stalks. A manopla was another stone accoutrement that was held in the hand and may have been used to hit the ball in a variation of the ballgame. We see in murals that sometimes sticks and bats were also used in smaller types of the game that were possibly played in areas away from the main courts. In some cases helmets were used to protect the head. Before and after the games we also see that elaborate headdresses were also worn by some of the ball players. Many players wore items that had certain animals in common, such as jaguars or deer. This leads many scholars to believe that ballgame teams had mascots not unlike modern sports teams. Figurines from the archaeological record show us that ball players were not always men. While the Mesoamerican ballgame was exclusively a male-dominated activity at the time of the Spanish conquest, clay figurines unearthed from the Olmec period in the Gulf Coast and the modern-day state of Guerrero show female players. The figurines date from 1300 BC to 100 BC. No female figurines or depictions of female ball players are found after that time.

Unearthed figurines, murals and other illustrations give us insight into the uniforms worn by ball game players and some of the equipment used. Players wore what are called yuquitos, leather or cloth pads which may have been used to protect the wrists, knees or shins. They were often decorated with a skull or human face. They would also wear a yoke around the waist that was almost like a girdle. This was made of heavy fabric, leather or wicker wood and may have also been used as protection against the fast-moving ball. Carved stone yokes were used ceremoniously before and after the ball games in place of the fabric, leather or wicker ones. The stone yokes are the only types that have survived and they are often elaborately decorated and inlaid with semi-precious stones. An hacha was a carved stone decoration in a shape of a hatchet blade that was attached to the yoke and was personalized to the player. Another stone accessory was a palma which was either held in place in the hand or attached to the yoke. Many times the palma was carved in the shape of maize stalks. A manopla was another stone accoutrement that was held in the hand and may have been used to hit the ball in a variation of the ballgame. We see in murals that sometimes sticks and bats were also used in smaller types of the game that were possibly played in areas away from the main courts. In some cases helmets were used to protect the head. Before and after the games we also see that elaborate headdresses were also worn by some of the ball players. Many players wore items that had certain animals in common, such as jaguars or deer. This leads many scholars to believe that ballgame teams had mascots not unlike modern sports teams. Figurines from the archaeological record show us that ball players were not always men. While the Mesoamerican ballgame was exclusively a male-dominated activity at the time of the Spanish conquest, clay figurines unearthed from the Olmec period in the Gulf Coast and the modern-day state of Guerrero show female players. The figurines date from 1300 BC to 100 BC. No female figurines or depictions of female ball players are found after that time.

The ballgame features prominently in the Maya creation story, as found in the Popol Vuh, the Postclassic Quiché Maya religious text from western Guatemala dictated to a Spanish priest. According to the creation story, the first humans on earth were two brothers, Vucub Hunahpu and Hun Hunahpu. They loved to play ball so much that the bouncing of their rubber ball disturbed the gods who lived in Xibalba, the underworld. The gods wanted to end this noise, so they invited the brothers to a game down in the netherworld. When the two arrived, they were killed and decapitated. Their heads were displayed in a tree. When the underworld goddess Xquic walked by, the head of Hun Hunahpu spat on her and she became pregnant. After this, she was exiled to the earth’s surface and gave birth to two boys who would later be called the “Hero Twins” named Hunahpu and Xbalanque. These half-god, half-human boys discovered the ball game equipment of their father and uncle and began playing the game. This again angered the gods below. The angry underworld lords tried to trick and kill the twins by luring them to the underworld and they escaped every time. In one of their visits below the twins recovered the bodies of their father and uncle, and placed them in the sky to become the sun and the moon.

The ballgame features prominently in the Maya creation story, as found in the Popol Vuh, the Postclassic Quiché Maya religious text from western Guatemala dictated to a Spanish priest. According to the creation story, the first humans on earth were two brothers, Vucub Hunahpu and Hun Hunahpu. They loved to play ball so much that the bouncing of their rubber ball disturbed the gods who lived in Xibalba, the underworld. The gods wanted to end this noise, so they invited the brothers to a game down in the netherworld. When the two arrived, they were killed and decapitated. Their heads were displayed in a tree. When the underworld goddess Xquic walked by, the head of Hun Hunahpu spat on her and she became pregnant. After this, she was exiled to the earth’s surface and gave birth to two boys who would later be called the “Hero Twins” named Hunahpu and Xbalanque. These half-god, half-human boys discovered the ball game equipment of their father and uncle and began playing the game. This again angered the gods below. The angry underworld lords tried to trick and kill the twins by luring them to the underworld and they escaped every time. In one of their visits below the twins recovered the bodies of their father and uncle, and placed them in the sky to become the sun and the moon.

While not much is known about the specifics of how the Mesoamerican ballgame was played, we do know that it remained important for thousands of years and was found across many cultures and geographies. There may not be one thing other than this game that can be found so consistently throughout ancient Mexico. As the world’s first team sport we can only imagine what would have happened if the Spanish hadn’t put an end to its widespread practice and the game, like maize, squash and tobacco, had been exported to other parts of the world. We will never know if this game would have become popular in other countries and would have become the first international competitive team sport. Instead, we have an important part of ancient Mexican life remaining somewhat mysterious and exclusively Mexican.

While not much is known about the specifics of how the Mesoamerican ballgame was played, we do know that it remained important for thousands of years and was found across many cultures and geographies. There may not be one thing other than this game that can be found so consistently throughout ancient Mexico. As the world’s first team sport we can only imagine what would have happened if the Spanish hadn’t put an end to its widespread practice and the game, like maize, squash and tobacco, had been exported to other parts of the world. We will never know if this game would have become popular in other countries and would have become the first international competitive team sport. Instead, we have an important part of ancient Mexican life remaining somewhat mysterious and exclusively Mexican.

REFERENCES (this is not a formal bibliography)

“El Ullamaliztli en el Siglo XVI”. Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl by Mercedes de la Garza Camino and Ana Luisa Izquierdo (in Spanish)

The Aztecs, the Maya and Their Predecessors by Muriel Porter Weaver

The Anthropology of Sport by Kendall Blanchard

Ancient Mesoamerica by Richard E. Blanton

2 thoughts on “The Mesoamerican Ballgame”

Once again Mr. Bitto you have made my week with this new chapter of Mexico Unesplained. The Mesoamerican Ballplayers was music to my ears.

A great idea has come through my head…. I Wil have my advanced English students listen to those podcasts of Mexico Unexplained and give them additional points with every shows they listen to.

Thank you Señor García. 🙂