Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

It was January of 1656. The English frigate Marston Moor arrived at Port Royal, Jamaica, after a few rough months at sea. The ship had left England for the West Indies a few months before with a new commander, a 30-year-old man from Norfolk named Christopher Myngs. The months at sea for the crew of the Marston Moor were rough not because of bad weather or run-ins with the Spanish fleet, but because their new commander was a harsh disciplinarian. The crew were at various stages of mutiny throughout the voyage and Captain Myngs – who had been at sea since the age of 13 -had a flair for quelling the insubordinate spirit of those who served under him. It was this type of person that the English government under the rule of Oliver Cromwell had wanted in their new possessions in the Caribbean. Jamaica, known as Santiago for over a century while under Spanish rule, had just come under English control the previous year in the early stages of the Anglo-Spanish War. Myngs had already proven himself during the First Anglo-Dutch War in the early 1650s, even capturing two Dutch men-of-war as prizes after attacking a fleet of Dutch ships. As England looked at expanding its possessions in the New World, it needed people like Myngs to deal with the Spanish. While stationed at Jamaica, Christopher Myngs became subcommander of the English naval flotilla based there and by 1658 he was promoted to full commander acting as what the English called a “commerce raider.” As a “commerce raider” Myngs led English naval vessels and ships manned by buccaneers to attack Spanish galleons and merchant vessels and he led a series of brutal attacks on Spanish settlements throughout the Caribbean. Myngs raided the coast of South America, sacking and burning the towns of Tolú and Santa María, then part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in the modern-day nation of Colombia. In 1659 he attacked a Spanish treasure fleet but failed to capture it and continued to plunder the Spanish colonies in northern South America, known collectively as the Spanish Main. Myngs was seen by the Spanish government as nothing less than a mass murderer or pirate and Spanish authorities appealed to the Cromwell government in England to have Myngs cease his activities in Spanish-controlled areas of the New World. The authorities in London turned a blind eye to Myngs’ misdeeds until word reached them that he had been sharing the loot from his plundering adventures 50-50 with the pirates who had sailed with him on his raids. Under the orders of Edward D’Oyley, the English commander of Jamaica, Myngs was arrested for embezzlement and sent back to England in 1660.

It was January of 1656. The English frigate Marston Moor arrived at Port Royal, Jamaica, after a few rough months at sea. The ship had left England for the West Indies a few months before with a new commander, a 30-year-old man from Norfolk named Christopher Myngs. The months at sea for the crew of the Marston Moor were rough not because of bad weather or run-ins with the Spanish fleet, but because their new commander was a harsh disciplinarian. The crew were at various stages of mutiny throughout the voyage and Captain Myngs – who had been at sea since the age of 13 -had a flair for quelling the insubordinate spirit of those who served under him. It was this type of person that the English government under the rule of Oliver Cromwell had wanted in their new possessions in the Caribbean. Jamaica, known as Santiago for over a century while under Spanish rule, had just come under English control the previous year in the early stages of the Anglo-Spanish War. Myngs had already proven himself during the First Anglo-Dutch War in the early 1650s, even capturing two Dutch men-of-war as prizes after attacking a fleet of Dutch ships. As England looked at expanding its possessions in the New World, it needed people like Myngs to deal with the Spanish. While stationed at Jamaica, Christopher Myngs became subcommander of the English naval flotilla based there and by 1658 he was promoted to full commander acting as what the English called a “commerce raider.” As a “commerce raider” Myngs led English naval vessels and ships manned by buccaneers to attack Spanish galleons and merchant vessels and he led a series of brutal attacks on Spanish settlements throughout the Caribbean. Myngs raided the coast of South America, sacking and burning the towns of Tolú and Santa María, then part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in the modern-day nation of Colombia. In 1659 he attacked a Spanish treasure fleet but failed to capture it and continued to plunder the Spanish colonies in northern South America, known collectively as the Spanish Main. Myngs was seen by the Spanish government as nothing less than a mass murderer or pirate and Spanish authorities appealed to the Cromwell government in England to have Myngs cease his activities in Spanish-controlled areas of the New World. The authorities in London turned a blind eye to Myngs’ misdeeds until word reached them that he had been sharing the loot from his plundering adventures 50-50 with the pirates who had sailed with him on his raids. Under the orders of Edward D’Oyley, the English commander of Jamaica, Myngs was arrested for embezzlement and sent back to England in 1660.

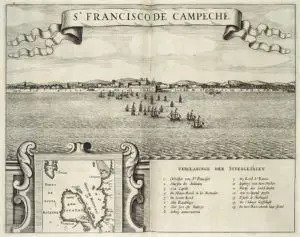

By 1662, after the monarchy was restored in England under Charles the Second, Myngs once again was sent to the West Indies in service of his country, this time as part of a covert operation to undermine Spanish power in the area. Even though the Anglo-Spanish War had ended, England still had plans to expand its possessions in the Caribbean and parts of the mainland of the Americas, and the Crown wanted Myngs to continue his strategy of employing pirates to assist him in attacking Spanish ships and towns, to seize wealth and destroy infrastructure. The new English governor of Jamaica, Thomas Hickman-Windsor, First Earl of Plymouth, completely supported Myngs’ endeavors and supplied him with ships and able-bodied men. By the end of 1662, Myngs and his small fleet of pirate ships attacked the heavily fortified city of Santiago de Cuba, a settlement on the southern part of the island of Cuba founded by the Spanish in 1515. The English commander made good on his promise and shared the wealth he plundered from Cuba with the pirates who helped him. After his Cuban victory Christopher Myngs announced a daring plan to sack the Spanish city of San Francisco de Campeche, now the capital of the Mexican state of Campeche, a somewhat unprotected but very wealthy town in the western Yucatán on the Gulf of Mexico. As news of Myngs’ attack on Santiago de Cuba spread throughout the Caribbean, he had no problem recruiting pirate volunteers from all parts of the region for his planned assault on Campeche. When the attack fleet gathered at Port Royal, Jamaica – including ships of French and Dutch privateers – it was the largest contingent of pirates ever assembled. Myngs would command over 1,400 pirates on over 20 vessels. In January of 1663, the fleet set sail for Mexico.

By 1662, after the monarchy was restored in England under Charles the Second, Myngs once again was sent to the West Indies in service of his country, this time as part of a covert operation to undermine Spanish power in the area. Even though the Anglo-Spanish War had ended, England still had plans to expand its possessions in the Caribbean and parts of the mainland of the Americas, and the Crown wanted Myngs to continue his strategy of employing pirates to assist him in attacking Spanish ships and towns, to seize wealth and destroy infrastructure. The new English governor of Jamaica, Thomas Hickman-Windsor, First Earl of Plymouth, completely supported Myngs’ endeavors and supplied him with ships and able-bodied men. By the end of 1662, Myngs and his small fleet of pirate ships attacked the heavily fortified city of Santiago de Cuba, a settlement on the southern part of the island of Cuba founded by the Spanish in 1515. The English commander made good on his promise and shared the wealth he plundered from Cuba with the pirates who helped him. After his Cuban victory Christopher Myngs announced a daring plan to sack the Spanish city of San Francisco de Campeche, now the capital of the Mexican state of Campeche, a somewhat unprotected but very wealthy town in the western Yucatán on the Gulf of Mexico. As news of Myngs’ attack on Santiago de Cuba spread throughout the Caribbean, he had no problem recruiting pirate volunteers from all parts of the region for his planned assault on Campeche. When the attack fleet gathered at Port Royal, Jamaica – including ships of French and Dutch privateers – it was the largest contingent of pirates ever assembled. Myngs would command over 1,400 pirates on over 20 vessels. In January of 1663, the fleet set sail for Mexico.

Campeche, originally known as San Francisco de Campeche, was founded by the Salamanca-born conquistador Francisco Montejo in 1540. When Montejo arrived to the area a Maya town had already existed at the site. The Maya called their settlement Ah Kim Pech, and it was first visited by the Spanish in 1517. Soon after the Spanish conquest of the area, San Francisco de Campeche became an important port on its own unique path of development as it was located far from the centralized Spanish authority in Mexico City. As trade with the Orient increased, Campeche became a point of embarkation for Asian valuables that crossed overland after landing on Mexico’s Pacific Coast. Galleons made regular runs to Spain out of Campeche and the city grew to be a regional center for trade. By the middle of the 1600s Campeche had become one of the wealthiest cities in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, but it lacked proper defenses which made it subject to small pirate raids and petty attacks from ships of other European powers. Famous pirates and privateers such as Sir Francis Drake, John Hawkins and Jean Lafitte had their runs at attacking Campeche, but nothing was to prepare the city for the huge armada of pirates which amassed at Jamaica in January of 1663.

Campeche, originally known as San Francisco de Campeche, was founded by the Salamanca-born conquistador Francisco Montejo in 1540. When Montejo arrived to the area a Maya town had already existed at the site. The Maya called their settlement Ah Kim Pech, and it was first visited by the Spanish in 1517. Soon after the Spanish conquest of the area, San Francisco de Campeche became an important port on its own unique path of development as it was located far from the centralized Spanish authority in Mexico City. As trade with the Orient increased, Campeche became a point of embarkation for Asian valuables that crossed overland after landing on Mexico’s Pacific Coast. Galleons made regular runs to Spain out of Campeche and the city grew to be a regional center for trade. By the middle of the 1600s Campeche had become one of the wealthiest cities in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, but it lacked proper defenses which made it subject to small pirate raids and petty attacks from ships of other European powers. Famous pirates and privateers such as Sir Francis Drake, John Hawkins and Jean Lafitte had their runs at attacking Campeche, but nothing was to prepare the city for the huge armada of pirates which amassed at Jamaica in January of 1663.

The flagship of the pirate fleet was the HMS Centurion captained by Christopher Myngs and its vice-flagship was named the Griffin. Among the pirates onboard the 20 or so ships in this flotilla were legends in their own time: Henry Morgan, Abraham Blauvelt and Edward Mansvelt. Along with these famous pirates were younger and lesser-known ones who would go on to become accomplished in the world of piracy after cutting their teeth with the Myngs Campeche fleet. Part of the pirate contingent arrived in Campeche Bay on the night of February 8, 1663, and 1,000 men landed a short distance from San Francisco de Campeche to take part in an overland raid. As word spread throughout the Caribbean of Myngs planned sacking of the city, the Spanish officials of the city had also known of the imminent attack but had little time to prepare. The city had always been very poorly fortified. At first light on the morning of February 9th, Spanish lookouts noticed the pirate ships in the bay and sounded the alarm, but it was already too late. The pirates attacked with their land-based forces at around 8:00 in the morning and the Spanish militia at Campeche, which numbered only about 150 armed men, did their best to repel the pirates which had surprised them by first attacking by land. The many pirate ships in the harbor fired their cannons and laid waste to coastal buildings as the land battle ensued. Many inhabitants of the city had fled and those who remained in the city fought fiercely. The entire affair lasted only about two hours. At the end of the morning the Spanish suffered 50 casualties with hundreds wounded, and the pirates had lost only 30

The flagship of the pirate fleet was the HMS Centurion captained by Christopher Myngs and its vice-flagship was named the Griffin. Among the pirates onboard the 20 or so ships in this flotilla were legends in their own time: Henry Morgan, Abraham Blauvelt and Edward Mansvelt. Along with these famous pirates were younger and lesser-known ones who would go on to become accomplished in the world of piracy after cutting their teeth with the Myngs Campeche fleet. Part of the pirate contingent arrived in Campeche Bay on the night of February 8, 1663, and 1,000 men landed a short distance from San Francisco de Campeche to take part in an overland raid. As word spread throughout the Caribbean of Myngs planned sacking of the city, the Spanish officials of the city had also known of the imminent attack but had little time to prepare. The city had always been very poorly fortified. At first light on the morning of February 9th, Spanish lookouts noticed the pirate ships in the bay and sounded the alarm, but it was already too late. The pirates attacked with their land-based forces at around 8:00 in the morning and the Spanish militia at Campeche, which numbered only about 150 armed men, did their best to repel the pirates which had surprised them by first attacking by land. The many pirate ships in the harbor fired their cannons and laid waste to coastal buildings as the land battle ensued. Many inhabitants of the city had fled and those who remained in the city fought fiercely. The entire affair lasted only about two hours. At the end of the morning the Spanish suffered 50 casualties with hundreds wounded, and the pirates had lost only 30  men of their attack force of 1,400. The lone Spanish governmental official who survived the battle negotiated the terms of surrender and the pirates were allowed to sack the city. The tally of the pirate booty included 150,000 Spanish pieces of eight, 14 vessels that were anchored in Campeche harbor and untold riches from private homes and merchants in the wealthy city. The pirate fleet left after 2 weeks and as soon as it sailed out of Campeche Bay many of the pirates went their own ways to various parts of the Caribbean and secret hideaways on the Spanish Main. Christopher Myngs had been injured during the Sack of Campeche and returned to England to recover. He was later named a vice admiral and was eventually knighted by the English king. Myngs died at sea in battle during the Second Anglo-Dutch War in 1666.

men of their attack force of 1,400. The lone Spanish governmental official who survived the battle negotiated the terms of surrender and the pirates were allowed to sack the city. The tally of the pirate booty included 150,000 Spanish pieces of eight, 14 vessels that were anchored in Campeche harbor and untold riches from private homes and merchants in the wealthy city. The pirate fleet left after 2 weeks and as soon as it sailed out of Campeche Bay many of the pirates went their own ways to various parts of the Caribbean and secret hideaways on the Spanish Main. Christopher Myngs had been injured during the Sack of Campeche and returned to England to recover. He was later named a vice admiral and was eventually knighted by the English king. Myngs died at sea in battle during the Second Anglo-Dutch War in 1666.

The pirate raid on Campeche had some lasting effects. The attack was so severe that the king of England, Charles the Second, forbade all future military adventures involving English naval officers and pirates. The city of Campeche rebuilt itself, and the Spanish, realizing the need for better fortifications invested in massive defensive works for the city. Work began in 1686 and would be finished decades later. French architect Louis Bouchard de Becour was hired to unify the fortifications and to supervise building the 2,650-meter-long wall which enclosed the city in an irregular hexagonal shape. At the corners of the hexagon were 8 defensive bastions named after saints or religious figures. The wall had two gates, a sea gate and a land gate. Two small forts were also built on hills outside the city.  The beefed up defenses did the trick and Campeche enjoyed a peaceful existence for most of the rest of its history. Many of the fortifications built in the 17th and 18th Centuries still survive to this day and are well preserved. The preservation of the parts of the city from the pirate era earned Campeche the status of a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. And what of the 1,400 pirates who took part in the Sack of Campeche? Many of them gained valuable experience and continued their careers as pirates on the open seas or as mercenary fighters for foreign governments. Many took their Mexican loot and settled down in England or made new lives for themselves in the recently-founded English colonies on the eastern shores of North America. Some set up little colonies of their own in the Caribbean region settling in places like the Mosquito Coast, the Bay Islands and the modern nation of Belize. Many descendants of these pirates still live in these areas today. Over 350 years after the raid on Campeche the pirate stories and legends survive in popular culture, and continue to evoke feelings of adventure and romance.

The beefed up defenses did the trick and Campeche enjoyed a peaceful existence for most of the rest of its history. Many of the fortifications built in the 17th and 18th Centuries still survive to this day and are well preserved. The preservation of the parts of the city from the pirate era earned Campeche the status of a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. And what of the 1,400 pirates who took part in the Sack of Campeche? Many of them gained valuable experience and continued their careers as pirates on the open seas or as mercenary fighters for foreign governments. Many took their Mexican loot and settled down in England or made new lives for themselves in the recently-founded English colonies on the eastern shores of North America. Some set up little colonies of their own in the Caribbean region settling in places like the Mosquito Coast, the Bay Islands and the modern nation of Belize. Many descendants of these pirates still live in these areas today. Over 350 years after the raid on Campeche the pirate stories and legends survive in popular culture, and continue to evoke feelings of adventure and romance.

REFERENCES

Konstam, Angust. Buccaneers 1620–1700, Oxford, 2000.

Marley, David. Historic cities of the Americas: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, Volume 1 p.223. ABC-CLIO, 2005.

Marley, David. Pirates of the Americas. ABC-CLIO, 2010.