Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the 1560s Friar Diego de Landa beheld a mighty structure in the jungle covered in trees and brush. Around him lay the ruins of a vanished civilization. The Maya guide told the Spanish-born priest that he stood in a place of great power and awesome significance and that the building in front of him still invoked a special reverence in the people who still lived in the area. The guide knew little more about the ancient city now called Chichén Itzá than Friar Diego, as much had been lost since the city had been abandoned some five centuries before. The Maya at the time of the Conquest called the ruined city Uuc-hab-nal, or in English, “Seven Places Full of Bushes.” New to the Yucatán, the future bishop knew he had to learn as much as possible about the new land’s past and present to make the conversion of the Indians go smoothly. In de Landa’s comprehensive work about the region called Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English, Reference of the Things of the Yucatán. he described in great detail the daily life, customs and beliefs of the Maya people to whom he ministered. Like many early members of the clergy in the New World, de Landa wanted to understand the people of his jurisdiction the best he could, so he observed things much like a cultural anthropologist would and took meticulous notes. He chronicled everything from the months and festivals of the Mayan calendar, to the significance of jewelry to Mayan women, to native military organization of the region, to genealogies of prominent Maya families. Some scholars believe that 90% of what we know of the Post-Classic and colonial-era Maya comes from de Landa’s Relación. In his book he described the great temple in the jungle and called it El Castillo, or “the castle” in English. We would know it later as the Temple of Kukulkan and it would become one of the most iconic and recognizable pyramids in the world.

In the 1560s Friar Diego de Landa beheld a mighty structure in the jungle covered in trees and brush. Around him lay the ruins of a vanished civilization. The Maya guide told the Spanish-born priest that he stood in a place of great power and awesome significance and that the building in front of him still invoked a special reverence in the people who still lived in the area. The guide knew little more about the ancient city now called Chichén Itzá than Friar Diego, as much had been lost since the city had been abandoned some five centuries before. The Maya at the time of the Conquest called the ruined city Uuc-hab-nal, or in English, “Seven Places Full of Bushes.” New to the Yucatán, the future bishop knew he had to learn as much as possible about the new land’s past and present to make the conversion of the Indians go smoothly. In de Landa’s comprehensive work about the region called Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English, Reference of the Things of the Yucatán. he described in great detail the daily life, customs and beliefs of the Maya people to whom he ministered. Like many early members of the clergy in the New World, de Landa wanted to understand the people of his jurisdiction the best he could, so he observed things much like a cultural anthropologist would and took meticulous notes. He chronicled everything from the months and festivals of the Mayan calendar, to the significance of jewelry to Mayan women, to native military organization of the region, to genealogies of prominent Maya families. Some scholars believe that 90% of what we know of the Post-Classic and colonial-era Maya comes from de Landa’s Relación. In his book he described the great temple in the jungle and called it El Castillo, or “the castle” in English. We would know it later as the Temple of Kukulkan and it would become one of the most iconic and recognizable pyramids in the world.

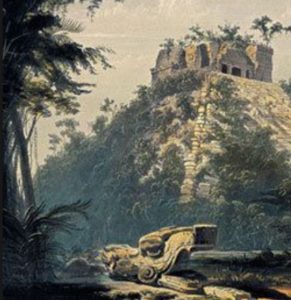

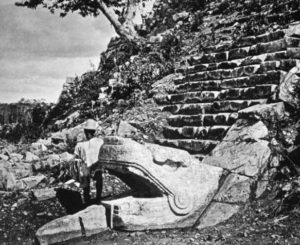

We next hear of the pyramid almost 3 centuries later from an American engineer named John Burke who went to the Yucatán in 1838 to help build a cotton factory in the town of Valladolid. In his time off, Burke explored the jungle and stumbled upon the overgrown city of Chichén Itzá along with other smaller ruins then located on large private land holdings. News of his findings made it to the larger newspapers in the United States and fueled the American imagination. A few years after Burke, John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood arrived at the site. The two were former adventure partners in the Middle East, and after US President Martin van Buren sent Stephens to the new Federal Republic of Central America as an ambassador of the United States, Stephens and Catherwood teamed up again. The two explored a total of 44 Maya sites throughout the region, including some of the larger cities like Uxmal, Copán, Palenque and Chichén Itzá. Stephens would eventually publish a book called Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán with all the illustrations done by Catherwood, who was an accomplished artist. The  two were the first to systematically survey Chichén Itzá and spent 18 days clearing, examining and documenting the ruins. For the first time since years after being abandoned the now-famous Temple of Kukulkan was stripped of most of its vegetation. Frederick Catherwood had much experience drawing and painting the monuments of the Near East and the Classical Mediterranean world, including those of the ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans. From this intimate knowledge of Old World architecture and design came Catherwood’s revolutionary declaration in the 1840s that the ruins of the Yucatán and Central America were made by people indigenous to the Americas and did not have any Old World Classical influence. It took some thirty more years before the next serious expedition to Chichén Itzá led by Augustus and Alice LePlongeon. The husband and wife team concentrated primarily on the Temple of Kukulkan and even discovered the famous reclining Chac-Mool sculpture, among other important finds. For more information about the LePlongeon discoveries at the pyramid, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 110 called “The Lost Continent of Mu and the Mexican Mother Civilization.” In the 1920s and 1930s, the El Castillo pyramid and other surrounding structures were restored by a joint effort between the Mexican government and the Carnegie Institute for Science in Washington DC. The 20th Century saw many other discoveries in, around and under the famous structure. Today, the northern and western faces of the pyramid have been completely restored along with the temple on top. The southern and eastern faces remain in ruin and are normally never seen in photographs.

two were the first to systematically survey Chichén Itzá and spent 18 days clearing, examining and documenting the ruins. For the first time since years after being abandoned the now-famous Temple of Kukulkan was stripped of most of its vegetation. Frederick Catherwood had much experience drawing and painting the monuments of the Near East and the Classical Mediterranean world, including those of the ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans. From this intimate knowledge of Old World architecture and design came Catherwood’s revolutionary declaration in the 1840s that the ruins of the Yucatán and Central America were made by people indigenous to the Americas and did not have any Old World Classical influence. It took some thirty more years before the next serious expedition to Chichén Itzá led by Augustus and Alice LePlongeon. The husband and wife team concentrated primarily on the Temple of Kukulkan and even discovered the famous reclining Chac-Mool sculpture, among other important finds. For more information about the LePlongeon discoveries at the pyramid, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 110 called “The Lost Continent of Mu and the Mexican Mother Civilization.” In the 1920s and 1930s, the El Castillo pyramid and other surrounding structures were restored by a joint effort between the Mexican government and the Carnegie Institute for Science in Washington DC. The 20th Century saw many other discoveries in, around and under the famous structure. Today, the northern and western faces of the pyramid have been completely restored along with the temple on top. The southern and eastern faces remain in ruin and are normally never seen in photographs.

When was the pyramid built? By whom? For what purpose? What else do we know about this structure? In the years after the Spanish Conquest, as mentioned previously, the local Maya insisted that the place was special, and certainly holy. The earliest pyramid structure built at the site of the Temple of Kukulkan dates to around 600 AD, but archaeologists theorize that older structures existed on the site before that and were razed to make way for more monumental architecture. The temple or successive temples appear to have been built over a sacred cenote, or sinkhole well, which are common throughout the Yucatán. The chasm underneath the pyramid measures 82 by 114 feet and has a depth of about 65 feet deep. The water filling this well is believed to run from north to south. Because of the existence of this cenote, only found in 2015 through a technique called electrical resistivity tomography, some scientists theorize that the site may have been considered sacred for many centuries before any physical structures were built there. Today, two distinct structures exist above the sacred cenote, both pyramids built on top of each other, with construction dates some three to four hundred years apart. The first pyramid, from about 600 AD dates from the Maya Classic period a century or so before the civilization’s overall collapse. The second structure, with its façade recognizable to many today, was constructed in the Eleventh Century after people from central Mexico, possibly the Toltecs, occupied and revived the city of Chichén Itzá. As a result of having a pyramid on top of a pyramid, there exists an interior gap between the buildings complete with the original structure’s staircase. Other tunnels and chambers exist inside the pyramid as well, including what has been dubbed the “Hall of Offerings,” the “Throne Room” and the “Chamber of Sacrifices.” Before the Mexican government closed the interior of El Castillo to tourists, one of the prized artifacts found inside the pyramid was still available for viewing by a curious public. A throne carved in a shape of a jaguar and painted red with cinnabar remains inside the pyramid where it was found. Scientists theorize that the jaguar throne, with its jade inlays and teeth made of mollusk shells, may have served as a ritual sacrifice to “decommission” the old temple before building the new pyramid on top of it.

When was the pyramid built? By whom? For what purpose? What else do we know about this structure? In the years after the Spanish Conquest, as mentioned previously, the local Maya insisted that the place was special, and certainly holy. The earliest pyramid structure built at the site of the Temple of Kukulkan dates to around 600 AD, but archaeologists theorize that older structures existed on the site before that and were razed to make way for more monumental architecture. The temple or successive temples appear to have been built over a sacred cenote, or sinkhole well, which are common throughout the Yucatán. The chasm underneath the pyramid measures 82 by 114 feet and has a depth of about 65 feet deep. The water filling this well is believed to run from north to south. Because of the existence of this cenote, only found in 2015 through a technique called electrical resistivity tomography, some scientists theorize that the site may have been considered sacred for many centuries before any physical structures were built there. Today, two distinct structures exist above the sacred cenote, both pyramids built on top of each other, with construction dates some three to four hundred years apart. The first pyramid, from about 600 AD dates from the Maya Classic period a century or so before the civilization’s overall collapse. The second structure, with its façade recognizable to many today, was constructed in the Eleventh Century after people from central Mexico, possibly the Toltecs, occupied and revived the city of Chichén Itzá. As a result of having a pyramid on top of a pyramid, there exists an interior gap between the buildings complete with the original structure’s staircase. Other tunnels and chambers exist inside the pyramid as well, including what has been dubbed the “Hall of Offerings,” the “Throne Room” and the “Chamber of Sacrifices.” Before the Mexican government closed the interior of El Castillo to tourists, one of the prized artifacts found inside the pyramid was still available for viewing by a curious public. A throne carved in a shape of a jaguar and painted red with cinnabar remains inside the pyramid where it was found. Scientists theorize that the jaguar throne, with its jade inlays and teeth made of mollusk shells, may have served as a ritual sacrifice to “decommission” the old temple before building the new pyramid on top of it.

As the pyramid is dedicated to the Mayan feathered serpent god Kukulkan – known in central Mexico as Quetzalcoatl – sculptures of plumed serpents run down the sides of the northern staircase terminating with heads at ground level. On the spring and autumnal equinoxes, the sun casts a shadow of a serpent on the northwestern staircase giving the illusion that a snake is crawling down the side of the pyramid. Ironically, some researchers chalk this up to coincidence noting that a snake-like shadow reveals itself for several weeks around the equinoxes. Others affirm that this phenomenon is because of the use of “sacred geometry” which is the purposeful positioning of sacred buildings so that they have spiritual meaning in their layout or location. Not only is the Temple of Kukulkan located on a cenote, the underground chasm is at the center of the intersection between four other sacred wells: the great “Sacred Cenote” of Chichén Itzá and the three others called Xtoloc, Kanjuyum and Holtún. Archaeologists believe that the temple is also aligned to the sun to indicate traditional planting and harvesting seasons. The eastern side of the temple is angled to the nadir sunrise and the western side is angled to the zenith sunset. This is not uncommon in Mesoamerican architecture. The entire structure is 79 feet high, not including the 20 more feet at the top for the box-like temple where rituals to the god Kukulkan were performed. Each side measures 181 feet across with 9 levels and each side has a staircase with 91 steps. When the steps are added together, and if we include the final “step” being the temple platform on top, we have a total of 365 steps, which equals the number of days in a year.

As the pyramid is dedicated to the Mayan feathered serpent god Kukulkan – known in central Mexico as Quetzalcoatl – sculptures of plumed serpents run down the sides of the northern staircase terminating with heads at ground level. On the spring and autumnal equinoxes, the sun casts a shadow of a serpent on the northwestern staircase giving the illusion that a snake is crawling down the side of the pyramid. Ironically, some researchers chalk this up to coincidence noting that a snake-like shadow reveals itself for several weeks around the equinoxes. Others affirm that this phenomenon is because of the use of “sacred geometry” which is the purposeful positioning of sacred buildings so that they have spiritual meaning in their layout or location. Not only is the Temple of Kukulkan located on a cenote, the underground chasm is at the center of the intersection between four other sacred wells: the great “Sacred Cenote” of Chichén Itzá and the three others called Xtoloc, Kanjuyum and Holtún. Archaeologists believe that the temple is also aligned to the sun to indicate traditional planting and harvesting seasons. The eastern side of the temple is angled to the nadir sunrise and the western side is angled to the zenith sunset. This is not uncommon in Mesoamerican architecture. The entire structure is 79 feet high, not including the 20 more feet at the top for the box-like temple where rituals to the god Kukulkan were performed. Each side measures 181 feet across with 9 levels and each side has a staircase with 91 steps. When the steps are added together, and if we include the final “step” being the temple platform on top, we have a total of 365 steps, which equals the number of days in a year.

And what will become of this monument in the 21st Century? In 2006, after a woman fell to her death while ascending a staircase on El Castillo, the Mexican government prohibited all climbing on monuments at Chichén Itzá, cordoned off the pyramid and forbade tourists access to the inside of the structure. In the mild frenzy connected with the supposed end of the Mayan calendar in December of 2012, Chichén Itzá saw multitudes of visitors with even some local folklorico groups performing the “Doomsday Dance” to herald a cataclysm that never came to pass. With a modern-day revival in old Mayan beliefs and a growth in traditional indigenous shamanism, the Mexican government has granted limited access to the Temple of Kukulkan to those practicing the old rituals. Declared one of the New 7 Wonders of the World in 2007, The Chichén Itzá archaeological zone gets about 1.5 million visitors a year and El Castillo is the most photographed building in all the ancient Maya sites. The popularity of this iconic pyramid and the increasing numbers of tourists coming to see it has generated more interest in restoration efforts at Chichén Itzá and will undoubtedly lead to more discoveries in and around the majestic sacred monument.

And what will become of this monument in the 21st Century? In 2006, after a woman fell to her death while ascending a staircase on El Castillo, the Mexican government prohibited all climbing on monuments at Chichén Itzá, cordoned off the pyramid and forbade tourists access to the inside of the structure. In the mild frenzy connected with the supposed end of the Mayan calendar in December of 2012, Chichén Itzá saw multitudes of visitors with even some local folklorico groups performing the “Doomsday Dance” to herald a cataclysm that never came to pass. With a modern-day revival in old Mayan beliefs and a growth in traditional indigenous shamanism, the Mexican government has granted limited access to the Temple of Kukulkan to those practicing the old rituals. Declared one of the New 7 Wonders of the World in 2007, The Chichén Itzá archaeological zone gets about 1.5 million visitors a year and El Castillo is the most photographed building in all the ancient Maya sites. The popularity of this iconic pyramid and the increasing numbers of tourists coming to see it has generated more interest in restoration efforts at Chichén Itzá and will undoubtedly lead to more discoveries in and around the majestic sacred monument.

REFERENCES

Stephens, John L. Incidents of Travel in Yucatan. New York: Dover Publications, 1963.

Weaver, Muriel Porter. The Aztecs, Maya and Their Predecessors. San Francisco: Academic Press, 1981.

The INAH Website (In Spanish)

One thought on “The Temple of Kukulkan, Pyramid of Mystery”

This will all end in crying