Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Pope Francis had made his decision. The date was March 23rd 2017. This first Latin American pope, the outgoing and unconventional Jesuit argentino decided he would fast-track to sainthood three Mexican indigenous children who died in the early decades of the 1500s. The Christian names of the three who would be known to the world as the “Child Martyrs of Tlaxcala” were Cristobal, Antonio and Juan. The case for sainthood for these three began on January 7th 1982 when Pope John Paul the Second declared them to be “Servants of God.” On his second visit to Mexico in May of 1990, Pope John Paul the Second furthered the cause of the Tlaxcalan martyred children and announced their beatification at the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico City. The Congregation for the Causes of Saints met in Vatican City on March 4th 2017 to approve the cause and to continue the children along the path to sainthood. This would require further investigation into their lives and whether or not they were associated with any miracles. The Congregation knew that Pope Francis had taken a special interest in the cause of sainthood for these children and its members were not surprised when the Holy Father bypassed the normal route taken for Catholic saints by issuing a papal decree stating that no customary confirmation of associated miracles would be required. The children had been killed in what is termed in odium fidei – in hatred of the faith – and had thus become the first people in the New World to die as martyrs for Christendom. That, apparently, was enough to warrant such special consideration for sainthood.

Pope Francis had made his decision. The date was March 23rd 2017. This first Latin American pope, the outgoing and unconventional Jesuit argentino decided he would fast-track to sainthood three Mexican indigenous children who died in the early decades of the 1500s. The Christian names of the three who would be known to the world as the “Child Martyrs of Tlaxcala” were Cristobal, Antonio and Juan. The case for sainthood for these three began on January 7th 1982 when Pope John Paul the Second declared them to be “Servants of God.” On his second visit to Mexico in May of 1990, Pope John Paul the Second furthered the cause of the Tlaxcalan martyred children and announced their beatification at the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico City. The Congregation for the Causes of Saints met in Vatican City on March 4th 2017 to approve the cause and to continue the children along the path to sainthood. This would require further investigation into their lives and whether or not they were associated with any miracles. The Congregation knew that Pope Francis had taken a special interest in the cause of sainthood for these children and its members were not surprised when the Holy Father bypassed the normal route taken for Catholic saints by issuing a papal decree stating that no customary confirmation of associated miracles would be required. The children had been killed in what is termed in odium fidei – in hatred of the faith – and had thus become the first people in the New World to die as martyrs for Christendom. That, apparently, was enough to warrant such special consideration for sainthood.

To understand the Three Martyred Children of Tlaxcala it is important to examine the world in which they lived. Where did they come from? What was life like in the area known as Tlaxcala? What was it like to be an indigenous child in the early days of colonial New Spain?

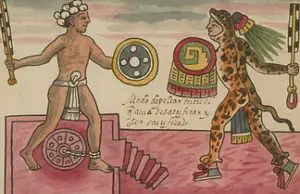

At the time of the first Spanish contact in 1519, Tlaxcala was an independent state and had been for about 150 years. It consisted of the cities of Tepetícpac Texcallan – also called Tlaxcala – Ocotelulco and Tizatlán just east of the Valley of Mexico, and the city of Quiahuitzlan which was founded later within the boundaries of the Valley of Mexico. The surrounding lands were fertile and supported a rather large population. The Tlaxcalan people were originally a conglomeration of 3 different ethnic groups speaking Nahuatl, Otomi and Pinome. Early on, the Nahua people dominated the state of Tlaxcala. This group of Tlaxcalans were closely related to the Aztecs whose empire nearly surrounded them. Tlaxcalan government was a very early example of a republic. As in the Aztec Empire there existed two classes in Tlaxcalan society, the pilli, or noble class, and the macehualli, or  commoners. Whether pilli or macehualli, Tlaxcalans could be elected to the government council of teteuctin, which consisted of anywhere between 50 and 200 men who proved their loyalty through service to the state. The Tlaxcalan council of teteuctin made a variety of decisions based on popular vote and is one of the earliest examples of representative government in the Americas. A constant in pre-Hispanic Tlaxcalan society was perpetual war with the Aztecs. Historians theorize that the small state of Tlaxcala could have easily been gobbled up by the Aztecs who had one of the most powerful military forces in the world, but the Aztec Empire preferred the never-ending state of war with their smaller neighbor. One of the captains of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés named Andres de Tapia once asked Emperor Montezuma why his empire just didn’t defeat this small state and be done with them. The Aztec emperor replied that wars with Tlaxcala provided excellent military training for his soldiers and ample captives for human sacrifices. Anthropologists refer to these series of conflicts between the Aztecs and Tlaxcalans as the “Flower Wars.” Both sides would fight according to a set of conventions including predetermined spots for battles and limited use of weapons so that fighters would engage in more hand-to-hand combat. For whatever reasons these wars occurred, the Tlaxcalans were worn down by them and when the Spanish arrived in their territory asking for men to march to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán to take on the Aztec Empire, thousands of Tlaxcalans volunteered to join the fight. As history shows, with Tlaxcalan help, the Spanish were the ultimate victors.

commoners. Whether pilli or macehualli, Tlaxcalans could be elected to the government council of teteuctin, which consisted of anywhere between 50 and 200 men who proved their loyalty through service to the state. The Tlaxcalan council of teteuctin made a variety of decisions based on popular vote and is one of the earliest examples of representative government in the Americas. A constant in pre-Hispanic Tlaxcalan society was perpetual war with the Aztecs. Historians theorize that the small state of Tlaxcala could have easily been gobbled up by the Aztecs who had one of the most powerful military forces in the world, but the Aztec Empire preferred the never-ending state of war with their smaller neighbor. One of the captains of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés named Andres de Tapia once asked Emperor Montezuma why his empire just didn’t defeat this small state and be done with them. The Aztec emperor replied that wars with Tlaxcala provided excellent military training for his soldiers and ample captives for human sacrifices. Anthropologists refer to these series of conflicts between the Aztecs and Tlaxcalans as the “Flower Wars.” Both sides would fight according to a set of conventions including predetermined spots for battles and limited use of weapons so that fighters would engage in more hand-to-hand combat. For whatever reasons these wars occurred, the Tlaxcalans were worn down by them and when the Spanish arrived in their territory asking for men to march to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán to take on the Aztec Empire, thousands of Tlaxcalans volunteered to join the fight. As history shows, with Tlaxcalan help, the Spanish were the ultimate victors.

Colonial life in Tlaxcala, the context in which we find the three martyred children, was slightly different from most of the rest of New Spain. As a reward for their help during the conquest of the Aztecs, the Spanish king granted the Tlaxcalans special privileges. The old republic of Tlaxcala remained somewhat intact for the next 300 years with the practice of limited self-government within the structure of the teteuctin which was allowed to continue. The Spanish had divided the Tlaxcalan homeland into 4 fiefdoms or, in Spanish, señoríos based loosely on the administrative regions that already existed in connection to the main cities of the old independent Tlaxcalan state and renamed the capital city of Tepetícpac Texcallan,  Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. The Tlaxcalans were given the highest status among all the indigenous people of New Spain. They had the right to carry guns and to ride horses. They could retain their noble titles and indigenous names. The first archbishopric established in colonial Mexico was in Tlaxcala, and the first archbishop, a 73-year old Dominican from Aragón named Julián Garcés, assumed the post in 1525 when the martyrs Cristobal, Antonio and Juan were still alive. In addition to his primary mission of evangelization, Archbishop Garcés fought for the rights of the indigenous, established welfare services, built a hospital, and started construction of the cathedral at Puebla. Much of what Julián Garcés wrote in his diaries and letters survives to this day. He wrote this general statement about the children found throughout his immediate ministry in Tlaxcala:

Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. The Tlaxcalans were given the highest status among all the indigenous people of New Spain. They had the right to carry guns and to ride horses. They could retain their noble titles and indigenous names. The first archbishopric established in colonial Mexico was in Tlaxcala, and the first archbishop, a 73-year old Dominican from Aragón named Julián Garcés, assumed the post in 1525 when the martyrs Cristobal, Antonio and Juan were still alive. In addition to his primary mission of evangelization, Archbishop Garcés fought for the rights of the indigenous, established welfare services, built a hospital, and started construction of the cathedral at Puebla. Much of what Julián Garcés wrote in his diaries and letters survives to this day. He wrote this general statement about the children found throughout his immediate ministry in Tlaxcala:

“The children of the Indians… learn more rapidly and with greater joy than the Spanish children the articles of faith in their order and the other prayers. They are not chattering or quarrelsome, nor stubborn, nor restless, nor arrogant, nor disapproving, nor ill-tempered, but agreeable, and very obedient to their teachers.

“They are very intelligent, so that they can be easily taught anything. When they are ordered to count, or read or write, paint, perform any type of manual or artisan work or art, they show great clarity, quickness and facility of mind in learning the basic principles.

“No one objects, no one mumbles, nor complains because all of the care and concern of the parents is to make sure that their sons make good progress in teachings of Christianity. They learn perfectly ecclesiastical song, as well as that of the organ and Gregorian chant and harmony to such a degree that foreign musicians are not needed.”

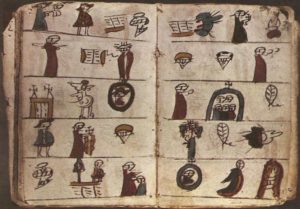

It was the Spanish king himself who suggested that the clergy in New Spain start the evangelization process with the children of native noble houses first and that their conversion to Christianity would set an example for others living under Spanish rule who had not yet completely accepted the new faith. Great effort was made by early missionaries to focus on children with two primary objectives in mind: Conversion to Christianity and to transmit useful knowledge and skills. The first thing clerics did was to try to learn the local indigenous languages by day through playing with the children, then compiling dictionaries and grammars at night. There were some 20 major and 100 minor languages in New Spain at the time of the conquest and this was a formidable task for the friars and priests, but as a whole, this group was very well educated and very patient. One of the first  of the clergy to arrive was a relative of the king of Spain himself, a Franciscan from Flanders named Pedro de Gante. De Gante came up with a catechism for the Indians done in the style of the old Aztec bark-paper pictographic books called codices. He also set up the first school to educate indigenous children called San José de Belén in the former Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. Many native noble families did not follow the Spanish king’s orders and instead of sending their sons off to be educated by the Dominicans and Franciscans, they sent young household servant boys in their places. This had the unintended effect of evangelizing the lower classes along with the upper classes. The king of Spain’s idea had the intended effect. As Archbishop Garcés said, the youngsters were quick learners and helpful, obedient students. More learned children often instructed other children. Bilingual children often worked closely with the clergy when it came to translation. And so, the children of New Spain adopted their new faith with zeal and spread it to their families. The evangelized became the evangelists. The newfound faith included with it the complete rejection of the old, and this caused strife within indigenous families. Here is where the story of the three Tlaxcalan martyrs begins.

of the clergy to arrive was a relative of the king of Spain himself, a Franciscan from Flanders named Pedro de Gante. De Gante came up with a catechism for the Indians done in the style of the old Aztec bark-paper pictographic books called codices. He also set up the first school to educate indigenous children called San José de Belén in the former Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. Many native noble families did not follow the Spanish king’s orders and instead of sending their sons off to be educated by the Dominicans and Franciscans, they sent young household servant boys in their places. This had the unintended effect of evangelizing the lower classes along with the upper classes. The king of Spain’s idea had the intended effect. As Archbishop Garcés said, the youngsters were quick learners and helpful, obedient students. More learned children often instructed other children. Bilingual children often worked closely with the clergy when it came to translation. And so, the children of New Spain adopted their new faith with zeal and spread it to their families. The evangelized became the evangelists. The newfound faith included with it the complete rejection of the old, and this caused strife within indigenous families. Here is where the story of the three Tlaxcalan martyrs begins.

Cristobal was born into a minor Tlaxcalan noble family in about 1514 or 1515, just a few years before the Spanish arrived in Mexico. When he was a young boy, Cristobal’s father, Acxotécatl, reluctantly sent him away to a Franciscan school. Acxotécatl didn’t concern himself too much with Cristobal’s evangelism until the boy started to destroy idols to the old gods that were still being venerated in the home. At that point, the boy’s father told him to stop immediately, but Cristobal continued with his personal crusade to eliminate all physical representations of the Nahua belief systems in the house. Acxotécatl grew more infuriated with his son the more “Spanish” he became and had thoughts of killing him. These thoughts were further encouraged by his second wife, Xochipapalotzin, Cristobal’s step mother. After one of Cristobal’s idol-smashing tirades, sometime in the year 1527, Acxotécatl took his son by the hair, dragged him through the house and beat him terribly so as to cause many broken bones. In his fury, the father took his son outside and threw him on to a pile of burning wood. Cristobal did not die immediately but suffered with his wounds until the next day. From his deathbed, Cristobal’s last words to Acxotécatl were, “Father, I forgive you.” Acxotécatl hastily buried Cristobal’s body in a room in their house but word quickly spread among the Tlaxcalans about what he had done. The Spanish authorities got involved and then sentenced Cristobal’s father to death for his crime.

Cristobal was born into a minor Tlaxcalan noble family in about 1514 or 1515, just a few years before the Spanish arrived in Mexico. When he was a young boy, Cristobal’s father, Acxotécatl, reluctantly sent him away to a Franciscan school. Acxotécatl didn’t concern himself too much with Cristobal’s evangelism until the boy started to destroy idols to the old gods that were still being venerated in the home. At that point, the boy’s father told him to stop immediately, but Cristobal continued with his personal crusade to eliminate all physical representations of the Nahua belief systems in the house. Acxotécatl grew more infuriated with his son the more “Spanish” he became and had thoughts of killing him. These thoughts were further encouraged by his second wife, Xochipapalotzin, Cristobal’s step mother. After one of Cristobal’s idol-smashing tirades, sometime in the year 1527, Acxotécatl took his son by the hair, dragged him through the house and beat him terribly so as to cause many broken bones. In his fury, the father took his son outside and threw him on to a pile of burning wood. Cristobal did not die immediately but suffered with his wounds until the next day. From his deathbed, Cristobal’s last words to Acxotécatl were, “Father, I forgive you.” Acxotécatl hastily buried Cristobal’s body in a room in their house but word quickly spread among the Tlaxcalans about what he had done. The Spanish authorities got involved and then sentenced Cristobal’s father to death for his crime.

The martyring of the second and third Tlaxcalan children – Antonio and Juan – happened together two years later. Antonio was the grandson of a prominent Tlaxcalan noble named Xiochténacti, and as the eldest grandson, Antonio was set to inherit his titles and lands. Juan was a servant to Antonio and around the same age; both boys were born in 1516 or 1517. Both also converted to Christianity at the same time and were evangelists for their new faith. They found themselves in a similar situation as Cristobal: The two were destroying indigenous idols in the name of Christianity and they were caught by disapproving adults. An angry mob formed, surrounded the two and clubbed the boys to death. This was 1529. Their bodies were hurled off a high cliff but were later recovered by a Domincan friar known to history only as Bernardino.

In a gathering of cardinals at Vatican City on April 20th 2017, it was announced that Cristobal, Antonio and Juan would be canonized in Rome on October 15th 2017. It was decided by the Pope that they would be the patron saints of Mexican childhood, serving as an example of piety for generations to come.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibilography)

Children in Colonial America by James Alan Marten

The Catholic Forum (online)

Santi e Beati (online)

4 thoughts on “The Child Martyrs of Tlaxcala”

Much enjoyed this, Robert. Appreciate your broad and thorough background information on early New Spain, and rich storytelling- not to mention your interest in the specific topic here. It definitely helped add to my thin knowledge about life in the early colonial days. Good stuff.

Thank you very much Bruce! I appreciate the comments and support.

This is really wonderful to read. I believe that I may have an apostolate to boys and men…somehow, somewhere. Meanwhile do these boys have a feast day? Where and when? Thank you for attracting my curiosity. May grace and peace be multiplied in you and all whom you love. Yours in Christ , Peter

Hi Peter, Their feast day is coming up: September 23. Thanks for your comments.