Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Sometime in the mid-1800s, in the sleepy town of San Miguel Coatlinchán between the Valley of Mexico and the Sierra Nevadas a man was gathering firewood near the Barranca de Santa Clara, a creek bed just outside of town. He stumbled on a massive stone carving, partially buried, that appeared to be Aztec. Little did he know, but the villager was face to face with the largest ancient monolith ever discovered in the Americas. Before the Spanish arrived and added the “San Miguel” to the town’s name, the indigenous village was simply called “Coatlinchán,” which in the Aztec language Nahuatl translates to “House of snakes.” The gigantic monolith drew the attention of townsfolk and others throughout the region who nicknamed the sculpture “La Piedra de los Tecomates,” or, in English, “The Stone of the Tecomates.” They named it this after the scooped-out carvings in the center of the piece which reminded the locals of tecomates, the gourd-like bowls used in the area. In 1889, with the monument fully cleaned and completely visible, Mexican artist and polymath José María Velasco painted the sculpture and declared the monolith to be a rendition of Chalchiuhtlicue, an Aztec goddess of rivers, streams, springs and baptism. In 1903 the pioneer Mexican archaeologist Leopoldo Batres identified it as Tlaloc, one of the principal Aztec gods and one of the oldest gods in ancient Mexico associated with rain and all things water-related. The people in the town soon started to ascribe magical powers to the statue and went to it much as they would a Catholic saint or virgin. If the small, scooped out parts of the statue – the tecomotes – were wet, or had some small amounts of water in them, that meant that it would rain. People made offerings to the monolith to ensure they had enough rain for their crops or to prevent flooding. Further study put the statue as having been made at around 800 AD, predating the Aztecs in the area by over 500 years. With a break of a few hundred years, the 20th Century villagers thus picked up where their ancestors left off, using the statue as it had been used for many centuries before the Spanish or even the Aztecs arrived in the area. All archaeologists know is that this sculpture of Tlaloc pre-dates the Aztecs by several centuries. They do not know which pre-Aztec culture is responsible for it, or why it was in this location. Although most likely in the same spot for over a thousand years, the modern Mexican government had other plans for Tlaloc. In 1963, with the building of the new National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, government officials wanted to move the statue from San Miguel Coatlinchán to the nation’s capital to serve as a focal point in front of the new museum. Very few people in the town wanted to part with the sculpture. The town council met and worked

Sometime in the mid-1800s, in the sleepy town of San Miguel Coatlinchán between the Valley of Mexico and the Sierra Nevadas a man was gathering firewood near the Barranca de Santa Clara, a creek bed just outside of town. He stumbled on a massive stone carving, partially buried, that appeared to be Aztec. Little did he know, but the villager was face to face with the largest ancient monolith ever discovered in the Americas. Before the Spanish arrived and added the “San Miguel” to the town’s name, the indigenous village was simply called “Coatlinchán,” which in the Aztec language Nahuatl translates to “House of snakes.” The gigantic monolith drew the attention of townsfolk and others throughout the region who nicknamed the sculpture “La Piedra de los Tecomates,” or, in English, “The Stone of the Tecomates.” They named it this after the scooped-out carvings in the center of the piece which reminded the locals of tecomates, the gourd-like bowls used in the area. In 1889, with the monument fully cleaned and completely visible, Mexican artist and polymath José María Velasco painted the sculpture and declared the monolith to be a rendition of Chalchiuhtlicue, an Aztec goddess of rivers, streams, springs and baptism. In 1903 the pioneer Mexican archaeologist Leopoldo Batres identified it as Tlaloc, one of the principal Aztec gods and one of the oldest gods in ancient Mexico associated with rain and all things water-related. The people in the town soon started to ascribe magical powers to the statue and went to it much as they would a Catholic saint or virgin. If the small, scooped out parts of the statue – the tecomotes – were wet, or had some small amounts of water in them, that meant that it would rain. People made offerings to the monolith to ensure they had enough rain for their crops or to prevent flooding. Further study put the statue as having been made at around 800 AD, predating the Aztecs in the area by over 500 years. With a break of a few hundred years, the 20th Century villagers thus picked up where their ancestors left off, using the statue as it had been used for many centuries before the Spanish or even the Aztecs arrived in the area. All archaeologists know is that this sculpture of Tlaloc pre-dates the Aztecs by several centuries. They do not know which pre-Aztec culture is responsible for it, or why it was in this location. Although most likely in the same spot for over a thousand years, the modern Mexican government had other plans for Tlaloc. In 1963, with the building of the new National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, government officials wanted to move the statue from San Miguel Coatlinchán to the nation’s capital to serve as a focal point in front of the new museum. Very few people in the town wanted to part with the sculpture. The town council met and worked  out a deal with federal officials. In exchange for surrendering Tlaloc to the national authorities, the town of San Miguel Coatlinchán would receive several public works projects, among them a paved junction with the Mexico-Texcoco highway, a new primary school, a health center, new water wells and state-of-the art pumping equipment for existing wells. The locals, who never wanted to part with this monumental piece of ancient art, were wary of the promises made by Mexico City politicians. When it came time to move the statue in 1964, the task was met with resistance at various stages. On February 23 of that year, a group of people destroyed the structures built to move the statue. They also deflated the tires on the massive flatbed truck that was specially created for the purpose of moving this 168-ton giant. After successive acts of sabotage, the government postponed the move. On April 16, 1964, the Mexican government sent in the army to occupy San Miguel Coatlinchán amid the protests of the locals. Dozens of workers using the most modern equipment labored for over an hour just to get the statue on the back of the flatbed truck. Ironically, on the short journey to Mexico City, the skies opened up, and it poured. The freak torrential rainstorm lasted for days. As it was not the rainy season, it was highly unusual for the area to experience what was then called one of the biggest storms ever to hit Mexico City in April. The people of San Miguel Coatlinchán were not surprised. This is what happens when you remove an old god from his happy home of 1,100 years. Tlaloc was obviously angry.

out a deal with federal officials. In exchange for surrendering Tlaloc to the national authorities, the town of San Miguel Coatlinchán would receive several public works projects, among them a paved junction with the Mexico-Texcoco highway, a new primary school, a health center, new water wells and state-of-the art pumping equipment for existing wells. The locals, who never wanted to part with this monumental piece of ancient art, were wary of the promises made by Mexico City politicians. When it came time to move the statue in 1964, the task was met with resistance at various stages. On February 23 of that year, a group of people destroyed the structures built to move the statue. They also deflated the tires on the massive flatbed truck that was specially created for the purpose of moving this 168-ton giant. After successive acts of sabotage, the government postponed the move. On April 16, 1964, the Mexican government sent in the army to occupy San Miguel Coatlinchán amid the protests of the locals. Dozens of workers using the most modern equipment labored for over an hour just to get the statue on the back of the flatbed truck. Ironically, on the short journey to Mexico City, the skies opened up, and it poured. The freak torrential rainstorm lasted for days. As it was not the rainy season, it was highly unusual for the area to experience what was then called one of the biggest storms ever to hit Mexico City in April. The people of San Miguel Coatlinchán were not surprised. This is what happens when you remove an old god from his happy home of 1,100 years. Tlaloc was obviously angry.

While the statue had been dated to around 800 AD, the worship of Tlaloc goes back centuries before that into the pre-Classic era of ancient Mexican history. When the Aztecs arrived in central Mexico from the north in around the year 1300 Tlaloc was already being worshipped there and the newcomers added the old rain god to their existing pantheon. The main pyramid temple in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán represents a sort of compromise between the old and new religions. Like many ancient Mexican pyramids, it had at its summit a platform of stone, on which two sanctuaries stood. The Aztecs dedicated the north one to the old god Tlaloc and the south one to their patron god Huitzilopochtli. So, the two forces that represented the prosperity of the earth, the rain and the sun, had equal footing on the top of the pyramid. Although Tlaloc imagery can be found as far back as 100 BC at sites such as Teotihuacán most of what researchers know of this god comes from Aztec accounts at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

While the statue had been dated to around 800 AD, the worship of Tlaloc goes back centuries before that into the pre-Classic era of ancient Mexican history. When the Aztecs arrived in central Mexico from the north in around the year 1300 Tlaloc was already being worshipped there and the newcomers added the old rain god to their existing pantheon. The main pyramid temple in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán represents a sort of compromise between the old and new religions. Like many ancient Mexican pyramids, it had at its summit a platform of stone, on which two sanctuaries stood. The Aztecs dedicated the north one to the old god Tlaloc and the south one to their patron god Huitzilopochtli. So, the two forces that represented the prosperity of the earth, the rain and the sun, had equal footing on the top of the pyramid. Although Tlaloc imagery can be found as far back as 100 BC at sites such as Teotihuacán most of what researchers know of this god comes from Aztec accounts at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

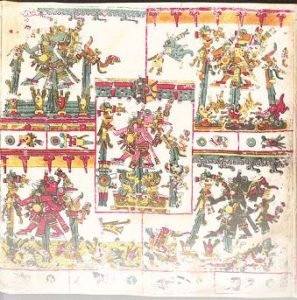

In most representations, Tlaloc has bulging eyes and fangs. He wears a headdress of feathers from the heron, one of the largest water birds found in the Mexican lake areas. Tlaloc also wears a garment of clouds and a necklace of jade. He carries a rattle said to make the sound of thunder and in some artistic representations he is surrounded by lightning bolts. In addition to bringing rain, Tlaloc also brought fertility to crops and people. Many ancient Mexican peoples referred to him as “the provider” because crops depended on whether or not he gave the earth valuable rains. Early Spanish chroniclers noticed the Aztecs’ mix of reverence and fear of the great god Tlaloc. While the god could bless crops with rain and smile down on the people and give them an abundant harvest, Tlaloc also could be very temperamental. He had the power to withhold rain and thus cause drought and famine. He could also punish man through floods, hailstorms and hurricanes. If a specific person angered him, Tlaloc could aim with precision and strike him down with a lightening bolt. Tlaloc ruled the fourth layer of heaven called Tlalocan, which the Aztecs described as a place of eternal springtime full of lush green vegetation and flowers. Tlalocan was the destination of people who died from water-related causes such as by drowning or from water-borne diseases. Those who died from a long list of specific diseases also went to Tlaloc’s level of heaven after death, included but not limited to, gout, scabies, sores, leprosy and venereal diseases. The souls of sacrificed children also found eternal rest among the green fields of Tlaloc’s fourth layer of heaven. Tlaloc was also the lord of the Third Sun, or the third incarnation of the physical universe. Tlaloc’s rule as the Third Sun ended with a great rain of fire which destroyed the earth and forced the gods to create everything anew, thus ushering in the epoch of the Fourth Sun.

As previously mentioned, Tlaloc played a major role in the pantheon of Aztec gods. Some sources claim that Tlaloc was the son of the principal creator god, Ometeotl. Most other sources at least put Tlaloc alongside Ometeotl in the earliest days of creation, dwelling with him in his paradise. Tlaloc’s first wife was Xochiquetzal, the beautiful goddess of youth and fertility. After the god Xipe Totec stole Xochiquetzal away from him, Tlaloc then married the minor water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue. The goddess helped Tlaloc, when broken down into his four aspects, to control the weather and water-related activities on earth. The Aztecs called four aspects of Tlaloc the Tlaloque, and each Tlaloque served a specific purpose. In English, the Tlaloque were the Western Rain, the Southern Rain, the Eastern Rain and the Northern Rain. The Western Rain, often depicted in red in illustrations, created the autumn rain. The Southern Rain, usually colored in green, created growth and plenty during the summer months. The Eastern Rain was responsible for the light rains of the springtime. The Aztecs represented this Tlaloque as the golden-colored Tlaloc. The Northern Rain aspect of Tlaloc created powerful storms, floods, hurricanes, hail and snow. This was the most feared Tlaloque and was revered as a destructive aspect of Tlaloc.

As previously mentioned, Tlaloc played a major role in the pantheon of Aztec gods. Some sources claim that Tlaloc was the son of the principal creator god, Ometeotl. Most other sources at least put Tlaloc alongside Ometeotl in the earliest days of creation, dwelling with him in his paradise. Tlaloc’s first wife was Xochiquetzal, the beautiful goddess of youth and fertility. After the god Xipe Totec stole Xochiquetzal away from him, Tlaloc then married the minor water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue. The goddess helped Tlaloc, when broken down into his four aspects, to control the weather and water-related activities on earth. The Aztecs called four aspects of Tlaloc the Tlaloque, and each Tlaloque served a specific purpose. In English, the Tlaloque were the Western Rain, the Southern Rain, the Eastern Rain and the Northern Rain. The Western Rain, often depicted in red in illustrations, created the autumn rain. The Southern Rain, usually colored in green, created growth and plenty during the summer months. The Eastern Rain was responsible for the light rains of the springtime. The Aztecs represented this Tlaloque as the golden-colored Tlaloc. The Northern Rain aspect of Tlaloc created powerful storms, floods, hurricanes, hail and snow. This was the most feared Tlaloque and was revered as a destructive aspect of Tlaloc.

For such an important god, the Aztecs observed many complex rites and rituals. As mentioned previously, they dedicated part of their great temple in the center of their capital to Tlaloc. The overseer of this part of the temple was a high priest with the title of Quetzalcoatl Tlaloc Tlamacazqui. Within the temple the priests made sure that the special bowl dedicated to Tlaloc always contained the heart of a sacrificial victim. Like many of the major Aztec gods, Tlaloc demanded human sacrifice, and he preferred children. Some researchers believe that this is because children had a greater tendency to cry before they were offered up to the gods, thus invoking the power of the water in the tears of children. Forty-four miles to the east of the great temple dedicated to Tlaloc in the center of the Aztec capital, the rain god had another sacred place on top of a mountain called Mount Tlaloc. In one of rare times during the year he ever left his palaces at Tenochtitlan, the Aztec emperor  himself would travel to Mount Tlaloc in the middle of February to attend the 3-week Tlaloc celebration called the Altcahualo. During the Altcahualo festival the Aztecs sacrificed thousands of children to Tlaloc on many mountaintops throughout the Aztec Empire, as the Aztecs believed that the spirit of the Tlaloque dwelled in mountain caves. Children were dressed elaborately, adorned with flowers and carried on wooden litters to the places of offering. The young victims were usually the children of slaves or the selected second-born offspring of the noble class. As the Tlaloc rituals took place at the same time on various mountaintops throughout the Aztec heartland, the Aztecs had a similar Tlaloc sacrificial ceremony on the shores of Lake Texcoco, limited to seven children. All the children who were sacrificed were destined for the fourth level of heaven, the green and flowery paradise of Tlalocan, and therefore were not cremated. Their bodies were dressed in paper, their foreheads were painted blue and seeds covered their faces before they were buried. In their hands, the priests placed digging sticks, to help them with planting in the afterlife. The winter festival to Tlaloc called Atemoztli did not include human sacrifice but rather involved a sacrifice performed on effigies. People created dolls out of amaranth and fashioned the dolls’ teeth out of pumpkin seeds and eyes out of beans. During the three-week festival, celebrants adorned the dolls with fineries and made small offerings to them much like a modern-day Catholic Mexican would do for a saint. At the end of the Atemoztli festival, participants would cut open the doll and ceremonially extract the heart, then the doll would be cut into pieces and was eaten. The shrine-like offerings surrounding the doll during the weeks of Atemoztli would then be burned.

himself would travel to Mount Tlaloc in the middle of February to attend the 3-week Tlaloc celebration called the Altcahualo. During the Altcahualo festival the Aztecs sacrificed thousands of children to Tlaloc on many mountaintops throughout the Aztec Empire, as the Aztecs believed that the spirit of the Tlaloque dwelled in mountain caves. Children were dressed elaborately, adorned with flowers and carried on wooden litters to the places of offering. The young victims were usually the children of slaves or the selected second-born offspring of the noble class. As the Tlaloc rituals took place at the same time on various mountaintops throughout the Aztec heartland, the Aztecs had a similar Tlaloc sacrificial ceremony on the shores of Lake Texcoco, limited to seven children. All the children who were sacrificed were destined for the fourth level of heaven, the green and flowery paradise of Tlalocan, and therefore were not cremated. Their bodies were dressed in paper, their foreheads were painted blue and seeds covered their faces before they were buried. In their hands, the priests placed digging sticks, to help them with planting in the afterlife. The winter festival to Tlaloc called Atemoztli did not include human sacrifice but rather involved a sacrifice performed on effigies. People created dolls out of amaranth and fashioned the dolls’ teeth out of pumpkin seeds and eyes out of beans. During the three-week festival, celebrants adorned the dolls with fineries and made small offerings to them much like a modern-day Catholic Mexican would do for a saint. At the end of the Atemoztli festival, participants would cut open the doll and ceremonially extract the heart, then the doll would be cut into pieces and was eaten. The shrine-like offerings surrounding the doll during the weeks of Atemoztli would then be burned.

Because Tlaloc was such an important god for so long in the history of ancient Mexico, the Spanish had a very difficult time eradicating devotion to this powerful deity. Modern-day visitors to Mexican churches built in the 1500s may see Tlaloc imagery incorporated with the traditional Catholic imagery. This may seem strange given that the accepted version of history tells us that the Spanish did everything they could to eradicate ancient Aztec practices. Perhaps in the early days of the Conquest Tlaloc was folded into the new religion just as the Aztecs had done when they entered the Valley of Mexico centuries before, but this time in a more subtle way. There is no denying the power of the belief surrounding this god however, as evidenced by the Tlaloc revival that seemed to spring out of nowhere in connection with the discovery of the gigantic statue at San Miguel Coatlinchán. Why this strong belief in this single god across thousands of years persists so strongly is an enduring mystery of ancient Mexico.

Because Tlaloc was such an important god for so long in the history of ancient Mexico, the Spanish had a very difficult time eradicating devotion to this powerful deity. Modern-day visitors to Mexican churches built in the 1500s may see Tlaloc imagery incorporated with the traditional Catholic imagery. This may seem strange given that the accepted version of history tells us that the Spanish did everything they could to eradicate ancient Aztec practices. Perhaps in the early days of the Conquest Tlaloc was folded into the new religion just as the Aztecs had done when they entered the Valley of Mexico centuries before, but this time in a more subtle way. There is no denying the power of the belief surrounding this god however, as evidenced by the Tlaloc revival that seemed to spring out of nowhere in connection with the discovery of the gigantic statue at San Miguel Coatlinchán. Why this strong belief in this single god across thousands of years persists so strongly is an enduring mystery of ancient Mexico.

REFERENCES

Clayton, Matt. Aztec Mythology. Independently published, 2018. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2Xy9vID

Díaz, Bernal. The Conquest of New Spain. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1963. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2XyBcpy

Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1961. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2JhYIya

Thomas, Hugh. Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés and the Fall of Old Mexico. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2xKsKUZ

2 thoughts on “Tlaloc, Beyond the Rain God”

I learned so much about Tlaloc thank you and I love your podcast.

Thank you!