Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

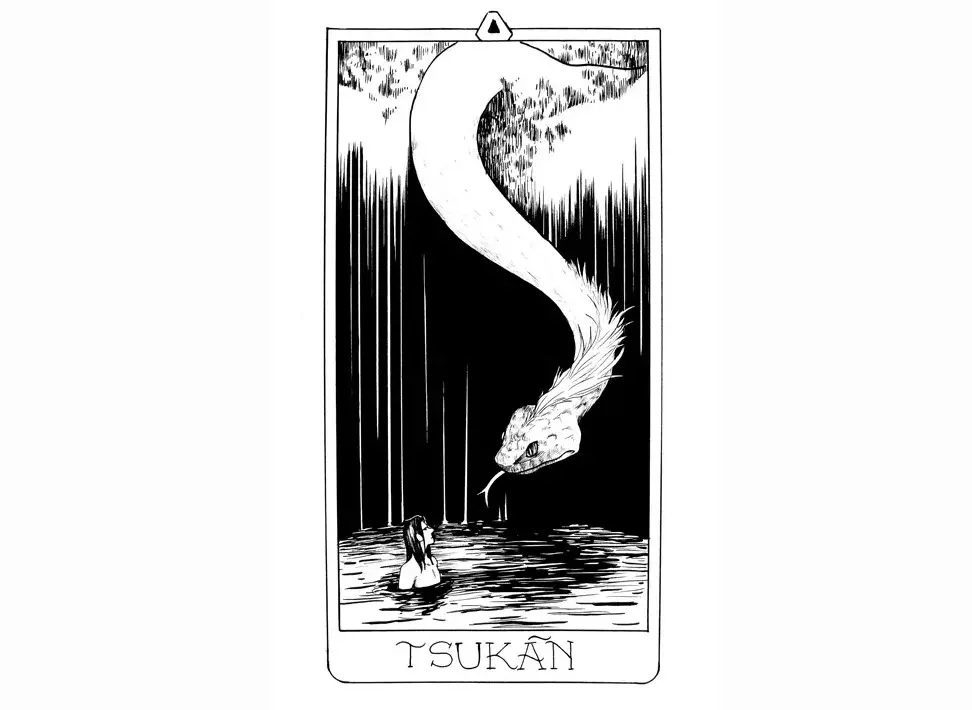

It was a warm August day in 2006. Gabriela Rivas Ochoa was walking home from helping her aunt at her small grocery and restaurant located on the outskirts of the town of Calcehtok about 25 miles southeast of Mérida, the capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán. Young Gabriela heard rustling in the dense vegetation on the side of the road and what she said she saw frightened her friends and family, but not the elders of the town. Gabriela claimed to have seen a dark green snake with a body as thick as a tree trunk with feathers or fur on the top of its head. She saw the creature only briefly as it slithered away rather quickly. Some in the town said Gabriela was making up the story for attention or was just seeing things. Others thought it was some sort of mutation or freak of nature, a snake that had grown abnormally large for some reason. The elders of this primarily indigenous town knew better though, and they were not afraid. Some chuckled and told those around them not to worry. Gabriela Rivas had seen a Tsukán, a very special ancient guardian of caves and cenotes, the limestone sinkholes discussed in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 251: https://mexicounexplained.com/cenotes-of-the-maya/. Some elders were delighted that the gigantic protector snake was still around as many had not heard stories of its appearance for many years.

It was a warm August day in 2006. Gabriela Rivas Ochoa was walking home from helping her aunt at her small grocery and restaurant located on the outskirts of the town of Calcehtok about 25 miles southeast of Mérida, the capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán. Young Gabriela heard rustling in the dense vegetation on the side of the road and what she said she saw frightened her friends and family, but not the elders of the town. Gabriela claimed to have seen a dark green snake with a body as thick as a tree trunk with feathers or fur on the top of its head. She saw the creature only briefly as it slithered away rather quickly. Some in the town said Gabriela was making up the story for attention or was just seeing things. Others thought it was some sort of mutation or freak of nature, a snake that had grown abnormally large for some reason. The elders of this primarily indigenous town knew better though, and they were not afraid. Some chuckled and told those around them not to worry. Gabriela Rivas had seen a Tsukán, a very special ancient guardian of caves and cenotes, the limestone sinkholes discussed in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 251: https://mexicounexplained.com/cenotes-of-the-maya/. Some elders were delighted that the gigantic protector snake was still around as many had not heard stories of its appearance for many years.

The word “Tsukán” is a combination of two words from Yucatec Maya: “tsuk,” meaning, “horse,” and “kaan,” meaning snake. The myth sometimes speaks of this snake as having a head as big as a horse’s, but language scholars point out that the word “horse” in this Maya language derives from the same word as the one used to describe the tufts of silk at the end of ripe corn on the stalk. When horses arrived in the Yucatán, the Maya people thought that the horse’s mane and tail looked like the tassels of silky fibers found at the end of cornhusks. So, while the Tsukán’s head may indeed be as big as a horse’s head, the “tsuk” part of the name probably comes from the pre-Hispanic word used to describe corn silk, which appears to be growing out of the creature’s head and back.

It is unknown how far back the story of Tsukán goes, although it is believed that the legend stretches back thousands of years. It is important to note that it is part of the current lore of the northern Yucatán and allegedly there have been modern sightings of this gigantic snake. As this creature is the guardian of caves and cenotes, there is not just one of them; according to the legend there is one Tsukán assigned to any given cenote or cave. The Tsukán is not considered to be a god or a spirit to the Maya, but it is more like a magical creature endowed with certain powers and special characteristics, much like the slender jungle Bigfoot creature of the Maya called the Sisimite described in Mexico Unexplained episode number 12: https://mexicounexplained.com/sisismite-mexicos-jungle-dwelling-bigfoot/ As guardian and protector of the cenotes and caves, it is the Tsukán’s job to make sure the cenotes and caves have ample water in them. The Tsukán is not hostile to humans and is indifferent to the presence of people in its territory. There is one story in northwestern Yucatán that tells of a farmer who wanted to rest and sat on what he thought was a big log, a  fallen tree. The log began to move and the farmer got up in fright, turned around and saw the Tsukán slowly slither away, seeming not to care that a human had been using it as an impromptu resting place. While the Tsukán will leave humans alone, it may attack if provoked in a very strong and obvious way, and bad luck is certain to befall the human who kills one. If one sees the Tsukán in the forest, it is best to have a live-and-let live approach. The experiencer should realize that there is nothing to fear from this gigantic creature whose primary mission is to help. The Tsukán eats smaller animals and particularly likes the taste of magpies, a bird called cheel by the Maya. When the Tsukán needs to eat, it opens its mouth and the heat of its breath kills and partially dissolves its food. Images of a fire-breathing dragon come to mind, but maybe on a milder scale. When the Tsukán becomes old, it grows wings and feathers and flies to the sea where it goes to die. A new, younger Tsukán will then take the place of the older one as the guardian of that specific cave or cenote.

fallen tree. The log began to move and the farmer got up in fright, turned around and saw the Tsukán slowly slither away, seeming not to care that a human had been using it as an impromptu resting place. While the Tsukán will leave humans alone, it may attack if provoked in a very strong and obvious way, and bad luck is certain to befall the human who kills one. If one sees the Tsukán in the forest, it is best to have a live-and-let live approach. The experiencer should realize that there is nothing to fear from this gigantic creature whose primary mission is to help. The Tsukán eats smaller animals and particularly likes the taste of magpies, a bird called cheel by the Maya. When the Tsukán needs to eat, it opens its mouth and the heat of its breath kills and partially dissolves its food. Images of a fire-breathing dragon come to mind, but maybe on a milder scale. When the Tsukán becomes old, it grows wings and feathers and flies to the sea where it goes to die. A new, younger Tsukán will then take the place of the older one as the guardian of that specific cave or cenote.

The story of the origins of the Tsukán is an interesting one and has been told and retold for generations. The legend involves the Maya rain god Chaac and begins in a time of a bad drought affecting the Maya homeland. Chaac was tasked with drawing water from below the earth and distributing it among the Maya settlements. The desperate rain god looked for water from above by flying on the back of a winged reptilian creature that looked somewhat like a Pteranodon or Pterodactyl. To Chaac’s dismay, all the rivers, lakes and cenotes were dry, and in despair he and his flying reptile decided to rest on a large log in a dried-out forest. Just like in the story involving the farmer previously mentioned, the log began to move, and Chaac and his winged reptilian companion soon realized they had been sitting on a huge snake. The two reacted in great shock, and that scared the gigantic serpent, causing it to become defensive. The snake opened its jaws and with one bite devoured the beast on which Chaac was riding. The rain god, filled with intense anger, climbed up the serpent’s back and lashed it with his whip. Suddenly, the snake began to sprout a mane from its neck, and Chaac held on to it as it tried to slither away rapidly.

“Who are you to whip me like that?” the enormous serpent Tsukán said, enraged.

“I am Chaac, Lord of Rain,” he replied. “And now I am your lord and master as well. You will take me to the sea to bring water to the cenotes that are empty, because surely you are the one who drank up all the water.”

Tsukán, even angrier, writhed violently to shake Chaac off his back, but all he did was make his mane catch fire. Suddenly, enormous wings appeared on the sides of Tsukán’s body, which he stretched out. He then took to the air and headed for the sea. When they arrived at the shore, Chaac filled hundreds of vessels with water and tied them to Tsukán’s back. The snake was amazed: it was the first time he had ever seen the ocean.

“I will not return to the caves,” said Tsukán. “I will stay at here at the sea. Here I have a lot of space and I can go wherever I want.”

“First you must finish your mission,” Chaac said.

“What mission?” Tsukán asked.

The mighty Chaac then proclaimed: “You are going to be in charge of watching over all the cenotes and caverns and they will never lack water. You will be the guardian of the water and only when you are old will I allow you to return to the sea.”

Chaac had deceived the gigantic serpent because he knew that Tsukán could rejuvenate forever. Heading back towards the cenotes, Tsukán knocked Chaac to the ground with a whip of his body, but the rain god waved his whip and caused a thunderclap that immediately killed the snake and turned him into thousands of drops of water that fell into the cenotes. The streams, caves and cenotes filled with water once again. Slowly, at the bottom of a cave, the drops of water condensed until they took the shape of a snake that grew and sprouted wings again. Tsukán left his refuge to go to the sea, but on his way, he found Chaac, who threw a powerful gust of wind at him. This sudden blast of air made Tsukán turn into rain once more. Although the maned and winged serpent always wanted to return to the sea, he was condemned, with his eternal death and reincarnation, to always keep the cenotes, caves and wells of the Yucatán supplied with ample water.

Chaac had deceived the gigantic serpent because he knew that Tsukán could rejuvenate forever. Heading back towards the cenotes, Tsukán knocked Chaac to the ground with a whip of his body, but the rain god waved his whip and caused a thunderclap that immediately killed the snake and turned him into thousands of drops of water that fell into the cenotes. The streams, caves and cenotes filled with water once again. Slowly, at the bottom of a cave, the drops of water condensed until they took the shape of a snake that grew and sprouted wings again. Tsukán left his refuge to go to the sea, but on his way, he found Chaac, who threw a powerful gust of wind at him. This sudden blast of air made Tsukán turn into rain once more. Although the maned and winged serpent always wanted to return to the sea, he was condemned, with his eternal death and reincarnation, to always keep the cenotes, caves and wells of the Yucatán supplied with ample water.

The northern Yucatán Peninsula is made of limestone and has no running surface water, so the people of the region have always relied upon liquid sustenance from cenotes, caves and wells. According to folklorists and other researchers, the purpose of the legend of the Tsukán is to help eliminate anxiety felt by people regarding the scarce resource of water. The story has a powerful and magical creature in charge of things serving as a guardian and protector. With something as important as water in the hands of such a capable creature, there is little need to worry because things will be well taken care of. By extension, by securing the water supply, the Tsukán ensures the survival of all life, including the plants and animals on which the Maya rely on for sustenance.

But what of contemporary stories of gigantic snakes spotted in the jungles and scrub forests of the Yucatán? Could the legend of the Tsukán be based on a cryptid, or previously unknown or unclassified animal? Does this huge serpent really exist? We will leave that discussion and investigation to the monster hunter shows, with the hope that an over-anxious investigator doesn’t kill a Tsukán, thus facing the consequences of constant bad luck or even worse.

REFERENCES

Evia Cervantes, Carlos. El mito de la serpiente Tsukán. Merida: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, 2007. (in Spanish)