Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1633. A ship in the chilly north Atlantic near the ancient French city of Saint-Malo found itself under siege by pirates. Among the passengers captured by the buccaneers was a boy of 13 who was fleeing England. The teenage boy had no money or valuables but explained to the pirates that had escaped from an English prison and was heading for the European continent. The boy had been convicted of sedition by Crown authorities for publishing pamphlets against the English king and had been arrested and jailed. He escaped the prison and found himself on that captured ship. The pirates took him in and for several years the boy fought alongside them and distinguished himself in battle.

The year was 1633. A ship in the chilly north Atlantic near the ancient French city of Saint-Malo found itself under siege by pirates. Among the passengers captured by the buccaneers was a boy of 13 who was fleeing England. The teenage boy had no money or valuables but explained to the pirates that had escaped from an English prison and was heading for the European continent. The boy had been convicted of sedition by Crown authorities for publishing pamphlets against the English king and had been arrested and jailed. He escaped the prison and found himself on that captured ship. The pirates took him in and for several years the boy fought alongside them and distinguished himself in battle.

The boy’s name was William Lamport. He was born in County Wexford, Ireland, around 1610. His parents, Richard and Alonsa Lamport, were from English merchant families which had settled in southern Ireland centuries before. The Lamports, as with similar merchant families of the area, saw their  autonomy diminish throughout the 16th Century as English Tudor control over Ireland increased. Their Catholic faith was also threatened by new laws enacted by King Henry the Eighth of England starting in the 1530s. William Lamport’s grandfather, Patrick Lamport, aligned himself with the traditional Irish nobility against the increasing power of the English in Ireland and actively resisted rule from London. In 1617, when William was 7 years old, his grandfather was captured and executed on the personal orders of King James the First of England. Soon after the execution, William Lamport and his brother John left Wexford for a Jesuit school in Dublin. The tutelage of the Jesuit fathers lasted for a few years, William then went to school in England at Gresham College, located in central London. He excelled in mathematics and Greek and it was there, as a young teen, where Lamport expanded his political conscience. It was at this time, as previously mentioned, when his activities landed him in jail and eventually into the hands of the pirates.

autonomy diminish throughout the 16th Century as English Tudor control over Ireland increased. Their Catholic faith was also threatened by new laws enacted by King Henry the Eighth of England starting in the 1530s. William Lamport’s grandfather, Patrick Lamport, aligned himself with the traditional Irish nobility against the increasing power of the English in Ireland and actively resisted rule from London. In 1617, when William was 7 years old, his grandfather was captured and executed on the personal orders of King James the First of England. Soon after the execution, William Lamport and his brother John left Wexford for a Jesuit school in Dublin. The tutelage of the Jesuit fathers lasted for a few years, William then went to school in England at Gresham College, located in central London. He excelled in mathematics and Greek and it was there, as a young teen, where Lamport expanded his political conscience. It was at this time, as previously mentioned, when his activities landed him in jail and eventually into the hands of the pirates.

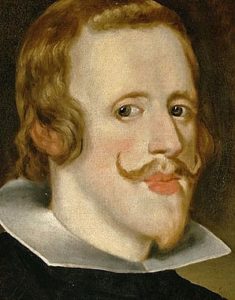

Young William said good-bye the pirates while harboring in Bordeaux, France sometime in the 1630s and made his way to a community of expatriate Irishmen living in La Coruña in northwestern Spain. He soon enrolled in the Colegio de Niños Nobles, a school for Irish exiles living in Spain located near the shrine of Santiago de Compostela, the notable destination of the Catholic World’s “Spanish Pilgrimage.” It was here in Spain where William Lamport Hispanicized his name to Don  Guillén Lombardo. It was also here where Lamport got the attention of Spanish and Irish nobles alike, and even the king of Spain, when he secured the allegiance to the Spanish king of the 250 members of the two pirate ships with whom he previously sailed. Thereafter, Lamport’s former pirate friends proved to be important mercenaries for the Spanish Crown and helped win victories in a few Spanish naval battles. Lamport was still a teenager when he received a scholarship to study at the College of the Irish in Salamanca. While at the college Lamport’s star seemed to be on the ascent and he was noticed by the Count-Duke of Olivares, the Spanish king’s principal minister. Lamport was then offered another scholarship to study at the elite Colegio de San Lorenzo de Escorial, a training ground for ambitious public servants of the Spanish government. When Lamport left his schooling he distinguished himself in the service of Spain’s King Phillip the Fourth on the battlefield, helping Spain win many campaigns in Europe. As the protégé of the Count-Duke of Olivares, the young Irishman also served in espionage and diplomatic missions on behalf of Spain throughout the European continent. Lamport even adopted Olivares’ principal last name, Guzmán, and later added that to his Hispanicized name thus becoming Don Guillén Lombardo de Guzmán. A favorite at the Spanish court in Madrid, Lamport became well connected with people in power and involved himself in politics. He became the chief architect of a plot to have the Spanish take over Ireland, which would have made the Emerald Isle a tribute-paying state within the Spanish Empire. Ultimately, Lamport’s plan was dismissed, but his ambitious nature was not squelched by this temporary setback.

Guillén Lombardo. It was also here where Lamport got the attention of Spanish and Irish nobles alike, and even the king of Spain, when he secured the allegiance to the Spanish king of the 250 members of the two pirate ships with whom he previously sailed. Thereafter, Lamport’s former pirate friends proved to be important mercenaries for the Spanish Crown and helped win victories in a few Spanish naval battles. Lamport was still a teenager when he received a scholarship to study at the College of the Irish in Salamanca. While at the college Lamport’s star seemed to be on the ascent and he was noticed by the Count-Duke of Olivares, the Spanish king’s principal minister. Lamport was then offered another scholarship to study at the elite Colegio de San Lorenzo de Escorial, a training ground for ambitious public servants of the Spanish government. When Lamport left his schooling he distinguished himself in the service of Spain’s King Phillip the Fourth on the battlefield, helping Spain win many campaigns in Europe. As the protégé of the Count-Duke of Olivares, the young Irishman also served in espionage and diplomatic missions on behalf of Spain throughout the European continent. Lamport even adopted Olivares’ principal last name, Guzmán, and later added that to his Hispanicized name thus becoming Don Guillén Lombardo de Guzmán. A favorite at the Spanish court in Madrid, Lamport became well connected with people in power and involved himself in politics. He became the chief architect of a plot to have the Spanish take over Ireland, which would have made the Emerald Isle a tribute-paying state within the Spanish Empire. Ultimately, Lamport’s plan was dismissed, but his ambitious nature was not squelched by this temporary setback.

While in Madrid Lamport fell in love with a minor noblewoman, Doña Ana de Cano y Leyva. It’s unclear whether Lamport married her of if they were in a state of unwed cohabitation. Doña Ana became pregnant with Lamport’s child at which point we see him flee Spain for the New World, perhaps to avoid a scandal or to leave an unhappy marriage. He was on a boat bound for Mexico on April 21st 1640, along with a new Viceroy, the Marqués de Villena. Some historical accounts state that Lamport was sent to Mexico City as a spy for his benefactor, the king’s chief minister the Count-Duke of Olivares. There was some unrest and dissatisfaction in Spain’s colonies in the Americas at the time and the minister needed someone whom he could trust to send accurate reports back to him in Spain. The causes of concern were coming from the population of New Spain’s criollos, or those of pure Spanish descent born in the New World. The criollos were protesting unfair treatment with regard to taxation and access to participation in government. In colonial Mexico, there existed a rigid social and racial hierarchy with peninuslares, or those newly arrived Spanish subjects born in Spain, at the top.

While in Madrid Lamport fell in love with a minor noblewoman, Doña Ana de Cano y Leyva. It’s unclear whether Lamport married her of if they were in a state of unwed cohabitation. Doña Ana became pregnant with Lamport’s child at which point we see him flee Spain for the New World, perhaps to avoid a scandal or to leave an unhappy marriage. He was on a boat bound for Mexico on April 21st 1640, along with a new Viceroy, the Marqués de Villena. Some historical accounts state that Lamport was sent to Mexico City as a spy for his benefactor, the king’s chief minister the Count-Duke of Olivares. There was some unrest and dissatisfaction in Spain’s colonies in the Americas at the time and the minister needed someone whom he could trust to send accurate reports back to him in Spain. The causes of concern were coming from the population of New Spain’s criollos, or those of pure Spanish descent born in the New World. The criollos were protesting unfair treatment with regard to taxation and access to participation in government. In colonial Mexico, there existed a rigid social and racial hierarchy with peninuslares, or those newly arrived Spanish subjects born in Spain, at the top.

In late 1640 Lamport arrived in Mexico City and rented a room from Don Fernando Carrillo, the Escribano Mayor, or Chief Clerk, for the Spanish government in Mexico City. The well-educated Lamport, who knew 14 languages, became the tutor to Carrillo’s son, Sebastián. It wasn’t long before Lamport began to move in influential circles among the criollo elite of New Spain, and sent a steady stream of well detailed reports to his benefactor the Count-Duke back at the Spanish Court in Madrid. Lamport appears to have gotten a little too close to his espionage subjects, though, and seemed to play a crucial role in the criollo conspiracy to overthrow the new Viceroy, the Marqués de Villena. The conspiracy was led by the Bishop of Puebla, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza. Lamport, who was sympathetic to the concerns of the criollos, served as a messenger between Bishop Palafox and Madrid, and eventually got the go-ahead from the Count-Duke of Olivares to oust Viceroy Villena. With the backing of Spanish troops, Bishop Palafox deposed the viceroy in June of 1642. Because of his pivotal role in this change of power, Lamport sought a position in the new regime of Bishop-Viceroy Palafox. As he was Irish and not a Spanish peninsular or even a criollo, Lamport was denied any role in the new Palafox government, and again his ambition was frustrated.

In late 1640 Lamport arrived in Mexico City and rented a room from Don Fernando Carrillo, the Escribano Mayor, or Chief Clerk, for the Spanish government in Mexico City. The well-educated Lamport, who knew 14 languages, became the tutor to Carrillo’s son, Sebastián. It wasn’t long before Lamport began to move in influential circles among the criollo elite of New Spain, and sent a steady stream of well detailed reports to his benefactor the Count-Duke back at the Spanish Court in Madrid. Lamport appears to have gotten a little too close to his espionage subjects, though, and seemed to play a crucial role in the criollo conspiracy to overthrow the new Viceroy, the Marqués de Villena. The conspiracy was led by the Bishop of Puebla, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza. Lamport, who was sympathetic to the concerns of the criollos, served as a messenger between Bishop Palafox and Madrid, and eventually got the go-ahead from the Count-Duke of Olivares to oust Viceroy Villena. With the backing of Spanish troops, Bishop Palafox deposed the viceroy in June of 1642. Because of his pivotal role in this change of power, Lamport sought a position in the new regime of Bishop-Viceroy Palafox. As he was Irish and not a Spanish peninsular or even a criollo, Lamport was denied any role in the new Palafox government, and again his ambition was frustrated.

A visit at the Carrillo residence from an indigenous miner from Taxco named Don Ignacio would change the course of Lamport’s life once again. Don Ignacio came seeking legal advice about the abuses the indigenous miners suffered at the hands of their Spanish overlords. Lamport met with Don Ignacio frequently and during one of the visits, the indigenous man introduced Lamport to peyote, the cactus with hallucinogenic properties. During one of the mescaline-induced peyote sessions, Don Ignacio claimed to see the future, where Lamport ruled over all of New Spain as an emperor. This fed Lamport’s ego and this ambitious young Irishman began a new project in the fall of 1642: laying out the first ever plan for Mexico’s independence from Spain.

A visit at the Carrillo residence from an indigenous miner from Taxco named Don Ignacio would change the course of Lamport’s life once again. Don Ignacio came seeking legal advice about the abuses the indigenous miners suffered at the hands of their Spanish overlords. Lamport met with Don Ignacio frequently and during one of the visits, the indigenous man introduced Lamport to peyote, the cactus with hallucinogenic properties. During one of the mescaline-induced peyote sessions, Don Ignacio claimed to see the future, where Lamport ruled over all of New Spain as an emperor. This fed Lamport’s ego and this ambitious young Irishman began a new project in the fall of 1642: laying out the first ever plan for Mexico’s independence from Spain.

Lamport worked diligently on his plan. His dream was to create a society in Mexico free of the rigid social and racial caste-like divisions imposed by the Spanish. Lamport envisioned Mexico as one of the most prosperous countries in the world if freedoms were granted and the economic restrictions from the mother country eliminated. As a colony of Spain, the Mexicans were required to send a fifth of everything mined back to Spain. Without the siphoning off of this “royal fifth,” or quinto, and with taxes imposed on New Spain kept in-country, Lamport imagined a land of unending prosperity. Additionally, there were severe trade restrictions in colonial Mexico that were hindering its progress. Under Lamport’s vision of an independent nation of Mexico, trade with the Orient and other nations of the world would flow freely, thus appealing to the sensibilities of the members of the wealthy criollo merchant class who had complained about trade restrictions for  generations. Social reforms would come with the economic ones. Lamport proposed complete legal equality under the law for all races and socio-economic classes, and in his plan he proposed the end of slavery and the elimination of forced labor drafts and tributes paid to the Crown by indigenous communities. Indian communities would be allowed to keep their languages, customs and laws. Popular assemblies would sprout up all over Mexico with an emphasis on decentralized power. The state would be ruled by a limited monarch, initially Lamport himself, who would be the first emperor of Mexico, who would lead the country with the consent of an active parliament elected by the people. If the monarch was a tyrant, he could be deposed by popular vote. In Lamport’s idyllic image of his new country, freed African slaves, wealthy peninsulares and marginalized members of impoverished indigenous communities would all participate in government and would have equal rights under a strictly codified law.

generations. Social reforms would come with the economic ones. Lamport proposed complete legal equality under the law for all races and socio-economic classes, and in his plan he proposed the end of slavery and the elimination of forced labor drafts and tributes paid to the Crown by indigenous communities. Indian communities would be allowed to keep their languages, customs and laws. Popular assemblies would sprout up all over Mexico with an emphasis on decentralized power. The state would be ruled by a limited monarch, initially Lamport himself, who would be the first emperor of Mexico, who would lead the country with the consent of an active parliament elected by the people. If the monarch was a tyrant, he could be deposed by popular vote. In Lamport’s idyllic image of his new country, freed African slaves, wealthy peninsulares and marginalized members of impoverished indigenous communities would all participate in government and would have equal rights under a strictly codified law.

Lamport was way ahead of his time with this line of thinking. What were his influences? Where did he get his sense of egalitarianism? Historians often credit Lamport’s sharp intellect and his ambitious nature for wanting to create a merit-based society free of ethnic and social barriers that he himself could not overcome in colonial New Spain. Others suggest that he was influenced by the writings of the 16th Century Dominican Friar Bartolomé de las Casas, an advocate for the rights of the indigenous in the Spanish colonies of the New World. What historians seem to overlook is Lamport’s time aboard the pirate ships in his formative teenage years. Modern-day historians and sociologists who have studied social organization and power structures on pirate ships in the 16th through 18th Centuries have discovered mini egalitarian, multicultural floating democracies among pirate communities during this time. Decisions were generally made collectively among the pirates whose crews were comprised of men of various races and ethnicities, social strata, ages and religious beliefs. Leaders arose in the pirate world not from noble birth or through courtly political connections but through ability. If leaders of pirate ships became tyrannical, they were deposed by popular consent, much like what Lamport proposed with regard to his limited monarchy. Perhaps Lamport formulated his ideas of creating an egalitarian society with merit and more democratic ideas replacing ancient social and racial norms as a result of his time as a teenage boy with the pirates.

In the fall of 1642, while working on his grand plans for an overhaul of Mexican society, Lamport tried to gain support for his plans from disgruntled criollo merchants, dissatisfied militia men and freed African slaves. He shared his vision and confided in a local criollo named Captain Méndez who eventually had Lamport arrested, but not on the charges of plotting against the Spanish government of New Spain. In October of 1642, Lamport was charged with heresy and arrested by the Spanish Inquisition for his use of peyote to invoke visions. The Spanish were generally appalled by indigenous drug use and saw it as something demonic and against the Catholic Church’s authority. Thus began Lamport’s lengthy incarceration, a full seventeen years behind bars. During his time in jail Lamport had access to pen and paper and was a prolific writer, authoring over 900 Latin psalms along with extensive political treatises and his own memoirs. During his time in jail it was rumored that Lamport was the illegitimate son of King Phillip the Third of Spain and thus the brother of the current Spanish king. Historians generally agree that this rumor was started – perhaps by Lamport himself – to give him a noble legitimacy in the eyes of the Mexican populace who had not yet been won over by his views of egalitarianism. Lamport escaped prison once, on Christmas of 1651. Many believe that the escape was allowed to happen and was helped along by Lamport’s cellmate who was acting as a spy. During his brief time free, Lamport tried contacting the Viceroy and also plastered central Mexico City with pamphlets denouncing the Spanish Inquisition which had imprisoned him. After his recapture, the escape was given as a justification to treat Lamport even more harshly and he was sent to solitary confinement. He was then sentenced to a public execution in 1659, to be burned at the stake as was customary for heretics under the rules of the Inquisition. Lamport remained defiant to the end, and before the flames of the executioner’s pyre could reach him, he strangled himself to death with the ropes they used to tie him to the stake, thus depriving the Inquisition of its public burning. So ended Mexico’s first, and perhaps most dramatic, bid for independence.

In the fall of 1642, while working on his grand plans for an overhaul of Mexican society, Lamport tried to gain support for his plans from disgruntled criollo merchants, dissatisfied militia men and freed African slaves. He shared his vision and confided in a local criollo named Captain Méndez who eventually had Lamport arrested, but not on the charges of plotting against the Spanish government of New Spain. In October of 1642, Lamport was charged with heresy and arrested by the Spanish Inquisition for his use of peyote to invoke visions. The Spanish were generally appalled by indigenous drug use and saw it as something demonic and against the Catholic Church’s authority. Thus began Lamport’s lengthy incarceration, a full seventeen years behind bars. During his time in jail Lamport had access to pen and paper and was a prolific writer, authoring over 900 Latin psalms along with extensive political treatises and his own memoirs. During his time in jail it was rumored that Lamport was the illegitimate son of King Phillip the Third of Spain and thus the brother of the current Spanish king. Historians generally agree that this rumor was started – perhaps by Lamport himself – to give him a noble legitimacy in the eyes of the Mexican populace who had not yet been won over by his views of egalitarianism. Lamport escaped prison once, on Christmas of 1651. Many believe that the escape was allowed to happen and was helped along by Lamport’s cellmate who was acting as a spy. During his brief time free, Lamport tried contacting the Viceroy and also plastered central Mexico City with pamphlets denouncing the Spanish Inquisition which had imprisoned him. After his recapture, the escape was given as a justification to treat Lamport even more harshly and he was sent to solitary confinement. He was then sentenced to a public execution in 1659, to be burned at the stake as was customary for heretics under the rules of the Inquisition. Lamport remained defiant to the end, and before the flames of the executioner’s pyre could reach him, he strangled himself to death with the ropes they used to tie him to the stake, thus depriving the Inquisition of its public burning. So ended Mexico’s first, and perhaps most dramatic, bid for independence.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

The Irish Zorro: The Extraordinary Adventures of William Lamport by Gerard Ronan

Between Court and Confessional: The Politics of Spanish Inquisitors by Kimberly Lynn

Memorias de un impostor: Don Guillén de Lampart, Rey de México by Vicente Riva Palacio (in Spanish)

2 thoughts on “William Lamport, Mexico’s Irish Would-Be King”

You could argue that he saw Mexico like the American Ireland: Both land conquered by outsiders, where their indigenous customs and languages were suppressed and they were subjected to a foreign king.

That’s great insight. I never thought of that angle before. Thanks for posting.