Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1998. In the eastern Sierra Madre of Mexico in a small indigenous village thirtysomething British adventurer Benedict Allen had been given permission by Huichol elders to take part in a month-long sacred pilgrimage to the mythical land of Wirikuta. The square-jawed, blond, Cheshire-born Allen stood head and shoulders above the Huichol elders who had also given permission to film parts of his journey to share his experiences with the outside world in a future BBC television show called “Last of the Medicine Men.” The future Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, who would later be rescued from peril in the jungles of New Guinea in late 2017, pioneered the technique of self-filming with a camcorder. Allen’s pilgrimage to Wirikuta was one of the first self-filmed and later televised adventures of its kind. He later wrote a book in the year 2000 with the same title as the television show and in it included a chapter dedicated to his Mexican adventure. In spite of what many considered a very public intrusion into the practices and lives of the largely undisturbed indigenous Huichol people, the outside world still seems to pass by these people who continue to live as their ancestors had for thousands of years.

The year was 1998. In the eastern Sierra Madre of Mexico in a small indigenous village thirtysomething British adventurer Benedict Allen had been given permission by Huichol elders to take part in a month-long sacred pilgrimage to the mythical land of Wirikuta. The square-jawed, blond, Cheshire-born Allen stood head and shoulders above the Huichol elders who had also given permission to film parts of his journey to share his experiences with the outside world in a future BBC television show called “Last of the Medicine Men.” The future Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, who would later be rescued from peril in the jungles of New Guinea in late 2017, pioneered the technique of self-filming with a camcorder. Allen’s pilgrimage to Wirikuta was one of the first self-filmed and later televised adventures of its kind. He later wrote a book in the year 2000 with the same title as the television show and in it included a chapter dedicated to his Mexican adventure. In spite of what many considered a very public intrusion into the practices and lives of the largely undisturbed indigenous Huichol people, the outside world still seems to pass by these people who continue to live as their ancestors had for thousands of years.

The Huichol call themselves the Wixáritari and currently live primarily in the Mexican states of Durango, Zacatecas, Jalisco and Nayarit. Most of the 10,000 or so Hiuichols living a somewhat traditional existence in the mountains of west Mexico are divided into 5 different rancherías or collections of ranchos, a system imposed upon them by the Spaniards during colonial times. It is very difficult to get to the 5 Huichol communities as the roads to them are unimproved and their locations are considered “remote.” Because of their isolation, the Huichols are considered to be one of the most  culturally intact native groups in the country of Mexico; they have maintained most of their culture and traditions well into modern times. Their religion has survived centuries of Catholicism and their language has survived generations of Huichols attending Mexican schools. Throughout their history this formidable people has had to deal with many pressures from the outside world, first from Chichimec marauders from the north, then from the Aztec Empire which tried to expand into their territory and finally from the Spanish royal and church authorities and then the government of the new nation of Mexico. The Huichols were not always mountain dwellers. Their oral history tells of a time when the tribe lived in the desert as hunters and gathers some 400 miles from their current homeland, emerging from a place called Wirikuta immediately after the heavens and the earth were created. Unlike many religions around the world whose followers believe in a mythical starting point – whether it be Eden or Aztlán – the Huichols can tell you the exact location of their primeval paradise. It is an area of the modern-day state of San Luis Potosí, an inhospitable piece of desert full of sacred spaces and where the magical peyote cactus grows. A pilgrimage is made to Wirikuta each year, taking between the harvesting and planting of maize.

culturally intact native groups in the country of Mexico; they have maintained most of their culture and traditions well into modern times. Their religion has survived centuries of Catholicism and their language has survived generations of Huichols attending Mexican schools. Throughout their history this formidable people has had to deal with many pressures from the outside world, first from Chichimec marauders from the north, then from the Aztec Empire which tried to expand into their territory and finally from the Spanish royal and church authorities and then the government of the new nation of Mexico. The Huichols were not always mountain dwellers. Their oral history tells of a time when the tribe lived in the desert as hunters and gathers some 400 miles from their current homeland, emerging from a place called Wirikuta immediately after the heavens and the earth were created. Unlike many religions around the world whose followers believe in a mythical starting point – whether it be Eden or Aztlán – the Huichols can tell you the exact location of their primeval paradise. It is an area of the modern-day state of San Luis Potosí, an inhospitable piece of desert full of sacred spaces and where the magical peyote cactus grows. A pilgrimage is made to Wirikuta each year, taking between the harvesting and planting of maize.

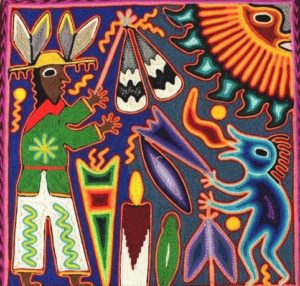

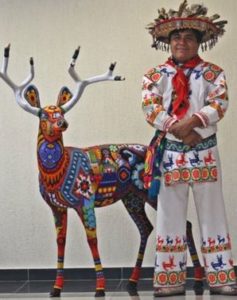

The Huichol pantheon is full of close to 120 “gods” but they are not the “gods” in the Christian or Western sense of the word. They are more like essences and energies of the things in the Huichol universe, some more powerful and more important than others. Everything possesses a certain life force or spirit, from rocks to animals to plants. It all started with Tatemari, or “Grandfather Fire,” who was present at the start of creation. He first created the sun whom the Huichols call Tayau. Tayau, or “Father Sun,” first emerged as a gigantic heart and is seen as a very powerful force who doles out various misfortunes as punishment or to serve as warnings. After the sun was made, Tatemari joined forces with Tatusi Nakawé, the Huichol great-grandmother creator deity, and finished creating the rest of the universe, putting various spirits and essences in charge of things. There is, for example, Tatei Utuanaka, the corn goddess who is also represented by the earth made fertile by rain, and Kauyumari, a sort of spiritual interface between man and the unseen realm personified in a deer. Kauyumari is seen as sort of a trickster who behaved questionably before becoming sacred. He is the one responsible for leading the Huichol to the sacred peyote plant which is then in turn responsible for the Huichol people becoming more in touch with the unseen spirit world. It is to Kauyumari they pray when they are on the final approach to the sacred land of Wikituri to ensure a good “hunt” of the peyote plant. In general, female spirits or deities are attached to things having to do with water, like rain, lakes and rivers. They also personify agriculture and growth, along with human and animal fertility. The male-oriented spirits or deities are attached to the hunt, the dry season and animals. Divine ancestors are also revered and respected. With the arrival of the first Catholic missionaries to Huichol territory in 1722 came incorporations of Christian elements into the Huichol religious system. The Virgin of Guadalupe, Jesus and some of the Christian saints, such as Saint Joseph, entered the religious pantheon of the Huichol and took their places among the animal and nature spirits. Each Huichol community, like most other towns throughout Mexico, has its respective patron saint, and that saint is celebrated with a feast day which incorporates all the other aspects of the Huichol belief system. The complex Huichol religion takes physical form in clothing and crafts. Artists weave supernatural stories into cloth used to make blouses, shirts and hats. Colorful Huichol yarn art and intricately fashioned beaded crafts are highly sought after by collectors not only throughout Mexico but around the world.

The Huichol pantheon is full of close to 120 “gods” but they are not the “gods” in the Christian or Western sense of the word. They are more like essences and energies of the things in the Huichol universe, some more powerful and more important than others. Everything possesses a certain life force or spirit, from rocks to animals to plants. It all started with Tatemari, or “Grandfather Fire,” who was present at the start of creation. He first created the sun whom the Huichols call Tayau. Tayau, or “Father Sun,” first emerged as a gigantic heart and is seen as a very powerful force who doles out various misfortunes as punishment or to serve as warnings. After the sun was made, Tatemari joined forces with Tatusi Nakawé, the Huichol great-grandmother creator deity, and finished creating the rest of the universe, putting various spirits and essences in charge of things. There is, for example, Tatei Utuanaka, the corn goddess who is also represented by the earth made fertile by rain, and Kauyumari, a sort of spiritual interface between man and the unseen realm personified in a deer. Kauyumari is seen as sort of a trickster who behaved questionably before becoming sacred. He is the one responsible for leading the Huichol to the sacred peyote plant which is then in turn responsible for the Huichol people becoming more in touch with the unseen spirit world. It is to Kauyumari they pray when they are on the final approach to the sacred land of Wikituri to ensure a good “hunt” of the peyote plant. In general, female spirits or deities are attached to things having to do with water, like rain, lakes and rivers. They also personify agriculture and growth, along with human and animal fertility. The male-oriented spirits or deities are attached to the hunt, the dry season and animals. Divine ancestors are also revered and respected. With the arrival of the first Catholic missionaries to Huichol territory in 1722 came incorporations of Christian elements into the Huichol religious system. The Virgin of Guadalupe, Jesus and some of the Christian saints, such as Saint Joseph, entered the religious pantheon of the Huichol and took their places among the animal and nature spirits. Each Huichol community, like most other towns throughout Mexico, has its respective patron saint, and that saint is celebrated with a feast day which incorporates all the other aspects of the Huichol belief system. The complex Huichol religion takes physical form in clothing and crafts. Artists weave supernatural stories into cloth used to make blouses, shirts and hats. Colorful Huichol yarn art and intricately fashioned beaded crafts are highly sought after by collectors not only throughout Mexico but around the world.

The keeper of the sacred traditions is called a marakame, but it is estimated that one half to one third of all Huichol people possess enough sacred knowledge to conduct curing rituals and to communicate with the divine through prayer and low-level ceremonies. The marakames practice their rites in a variety of sacred spaces. A round house or tuki which translates to “big house” in the Huichol language, serves as a sort of temple. The tuki always has a door facing east and a fireplace to honor the god Tatemari. There is usually a hole in the center of the roof and a hole at the center of the floor of the tuki to allow the flow of celestial and underground spirits into the temple. People can leave offerings or light candles in the tuki much as they would in a church. Every small Huichol community also has a sanctuary called an urukame. The urukame houses a sacred bundle comprised of an arrow and a bound rock crystal which is used as a representation of an important deceased member of the community, usually a shaman. This bundle serves as a sort of guardian of the community. In addition to the temples and sanctuaries known as tukis and urukames, there are many other smaller sacred shrines located throughout Huichol country with some found as far away as Lake Pátzcuaro in Michoacán.

The keeper of the sacred traditions is called a marakame, but it is estimated that one half to one third of all Huichol people possess enough sacred knowledge to conduct curing rituals and to communicate with the divine through prayer and low-level ceremonies. The marakames practice their rites in a variety of sacred spaces. A round house or tuki which translates to “big house” in the Huichol language, serves as a sort of temple. The tuki always has a door facing east and a fireplace to honor the god Tatemari. There is usually a hole in the center of the roof and a hole at the center of the floor of the tuki to allow the flow of celestial and underground spirits into the temple. People can leave offerings or light candles in the tuki much as they would in a church. Every small Huichol community also has a sanctuary called an urukame. The urukame houses a sacred bundle comprised of an arrow and a bound rock crystal which is used as a representation of an important deceased member of the community, usually a shaman. This bundle serves as a sort of guardian of the community. In addition to the temples and sanctuaries known as tukis and urukames, there are many other smaller sacred shrines located throughout Huichol country with some found as far away as Lake Pátzcuaro in Michoacán.

The biggest Huichol religious ritual is the annual pilgrimage to the mythical land of Wirikuta located in the deserts of the state of San Luis Potosí. It is in Wirikuta where the pilgrims gather the sacred peyote cactus which has mild mind-altering properties used to connect the Huichol to the divine. As the cactus grows hundreds of miles from home, the participants in the pilgrimage must bring back enough of the peyote to last the whole year. In years past the trek to Wirikuta was made on foot or by donkey. Since the 1960s the pilgrimage route has been crisscrossed by some major freeways and land along the way has been fenced off by farmers and ranchers who have denied Huichol passage through their lands. The Huichol have found a modern-day solution to these problems: to make the annual pilgrimage to Wirikuta, they charter a bus. While not a direct route, the bus stops at all of the important sacred sites along the way and shaves a few months off of the journey, allowing pilgrims to walk part of the way and ride part of the way. The first stop is near the border of the states of Jalisco and Zacatecas. At this stop, first-time pilgrims called primeros, who make most of the journey blindfolded, are encouraged to confess their sins to purify their souls. The marakanes symbolically whip the initiates to punish them for their transgressions and to aid in the purification process. The period of confession lasts the entire journey and everyone participates, even the most  seasoned marakane or shaman. As part of the purification, pilgrims also eat very little, sometimes just one orange and one tortilla per day. Along the journey the marakanes start to rename physical features and plants and animals to get the pilgrims to change the way they think about their physical reality. A shaman may proclaim that a tree is now called a whale, a bird is now called a pig. They leave their old world behind and enter a new one by renaming their physical reality. The head shaman or marakane on this pilgrimage even calls himself Tatemari, the grandfather fire god who started it all. The nighttime stops along the journey see the building of ritual fires and the continuation of the confessions of sins. As the group gets closer and closer to the sacred land of Wirikuta, the pilgrims have no secrets from one another and there is a great sense of cohesion among them. The last stop before they reach that part of Wirikuta where the sacred cactus grows is a sacred spring which has been fenced off by the Mexican government with special access afforded to the Huichols for their ceremonies. Even in spite of the fences and signs, people from the local town have used the area as a dumping ground and sometimes the water is too polluted to drink. Since the water is sacred, it is still gathered up to take back to the Huichol villages as a tangible piece of Wirikuta to be used in ceremonies. When the pilgrims arrive in the area of the peyote, called hikuri in the Huichol language, they pray to the deer spirit for a successful harvest. They gather up the cactus in huge baskets to make sure they have enough for the whole year back in the villages. After gathering sufficient quantities of the cactus, the marakanes lead the group in a ceremonial eating of the cactus, but only after elaborately decorated sacred arrows carrying the prayers from people back home, are placed in the ground. The plant produces mild mind-altering effects and pilgrims are left to their own visions and dreams after the initial ingestion of the cactus. When the effects wear off, in some hours’ time, the pilgrims board the bus and head for home, but not before climbing a sacred mountain at dawn and greeting the sun god. The sun then follows them west from Wirikuta to their respective villages in the western sierras.

seasoned marakane or shaman. As part of the purification, pilgrims also eat very little, sometimes just one orange and one tortilla per day. Along the journey the marakanes start to rename physical features and plants and animals to get the pilgrims to change the way they think about their physical reality. A shaman may proclaim that a tree is now called a whale, a bird is now called a pig. They leave their old world behind and enter a new one by renaming their physical reality. The head shaman or marakane on this pilgrimage even calls himself Tatemari, the grandfather fire god who started it all. The nighttime stops along the journey see the building of ritual fires and the continuation of the confessions of sins. As the group gets closer and closer to the sacred land of Wirikuta, the pilgrims have no secrets from one another and there is a great sense of cohesion among them. The last stop before they reach that part of Wirikuta where the sacred cactus grows is a sacred spring which has been fenced off by the Mexican government with special access afforded to the Huichols for their ceremonies. Even in spite of the fences and signs, people from the local town have used the area as a dumping ground and sometimes the water is too polluted to drink. Since the water is sacred, it is still gathered up to take back to the Huichol villages as a tangible piece of Wirikuta to be used in ceremonies. When the pilgrims arrive in the area of the peyote, called hikuri in the Huichol language, they pray to the deer spirit for a successful harvest. They gather up the cactus in huge baskets to make sure they have enough for the whole year back in the villages. After gathering sufficient quantities of the cactus, the marakanes lead the group in a ceremonial eating of the cactus, but only after elaborately decorated sacred arrows carrying the prayers from people back home, are placed in the ground. The plant produces mild mind-altering effects and pilgrims are left to their own visions and dreams after the initial ingestion of the cactus. When the effects wear off, in some hours’ time, the pilgrims board the bus and head for home, but not before climbing a sacred mountain at dawn and greeting the sun god. The sun then follows them west from Wirikuta to their respective villages in the western sierras.

That sacred mountain which is the last stop for the pilgrims in Wirikuta before returning home, was recently purchased by a Canadian mining company. Even though the United Nations through UNESCO has declared the Wirikuta area a protected cultural zone and the state of San Luis Potosí has stepped in to try to stop mining operations in the area, the mining company is continuing with their plans for strip mining the sacred lands. The Huichol plan on making their annual pilgrimage to Wirikuta anyway, as they have for untold years. Neither trash in their sacred springs, nor fences from landowners nor threats from international corporations will extinguish the flaming spirit of Tatemari and the Huichol’s sacred journey to the mythical land of Wirikuta.

REFERENCES

Allen, Benedict. Last of the Medicine Men. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2000.

Schaefer, Stacy B., and Peter T. Furst. People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, and Survival. Albuquerque, N.M: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.