Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

By the late 1700s the Office of the Holy Inquisition in Mexico threw its hands in the air and began questioning the reasons behind investigating so many instances of magical practices and supposed pacts with the devil that had come across its desks at its headquarters in Mexico City. Long the gatekeeper of official Catholicism and morality in New Spain, the Inquisition was being overrun with cases of sorcery and witchcraft and reports of written pacts with the Devil on the eve of Mexican Independence. Inquisitors often ignored these reports and did not even bother investigating them. Society in late colonial Mexico had become too diverse, too complex and too spread out over a vast geographical area for the Inquisition to keep up. The records from this time left behind for scholars to study are numerous, and before examining a few case studies, we will offer a bit of context and background.

By the late 1700s the Office of the Holy Inquisition in Mexico threw its hands in the air and began questioning the reasons behind investigating so many instances of magical practices and supposed pacts with the devil that had come across its desks at its headquarters in Mexico City. Long the gatekeeper of official Catholicism and morality in New Spain, the Inquisition was being overrun with cases of sorcery and witchcraft and reports of written pacts with the Devil on the eve of Mexican Independence. Inquisitors often ignored these reports and did not even bother investigating them. Society in late colonial Mexico had become too diverse, too complex and too spread out over a vast geographical area for the Inquisition to keep up. The records from this time left behind for scholars to study are numerous, and before examining a few case studies, we will offer a bit of context and background.

What exactly was the Office of the Holy Inquisition? What is known today by historians as the Mexican Inquisition was an extension of the Spanish Inquisition in the New World, arriving to New Spain officially in 1571, some 50 years after the fall of the Aztec Empire. The Inquisition was established primarily to root out heretics who would challenge the dogma and authority of the Catholic Church. Despite its horrible reputation, the Inquisition in Mexico was more lenient and somewhat paternal in the way it dealt with the accused. According to some researchers, only about 50 people were executed by the Office of the Holy Inquisition in Mexico City out of the thousands of cases brought before the office during its entire time in existence from 1571 to 1820. Even though the indigenous of Mexico suffered greatly at the hands of priests, missionaries and Spanish government officials during the colonial period, they were not subject to the Office of the Holy Inquisition. This rule was in place at the  Inquisition’s inception in 1571 when the King of Spain declared: “That the inquisitors should never proceed against the Indians, but against the old Christians and their descendants and other persons against whom in these kingdoms of Spain it is customary to proceed.” This included Spanish peninsulares, or immigrants from Spain in the New World, as well as criollos, or Spaniards born in Mexico, and a whole host of other castes and racial classifications excluding those who identified as being indigenous or who lived in indigenous communities. Researchers have cited the overwhelming number of women of African descent who show up in the records of the Inquisition in colonial Mexico. Many enslaved people, their descendants and the offspring of those who intermarried with other ethnic groups in Mexico, continued to practice African folk medicine and traditional African magic generations removed from their African origins, and were often quizzed by the minions of the Holy Office to see if what they were doing violated church dogma. Because there was a lot of cultural diffusion during the colonial era in Mexico, it was not uncommon for people of different ethnic backgrounds to share folk religious traditions and magical practices. An example of this would be the use of hummingbirds or hummingbird bones in rituals or magic potions. In colonial Mexico, the breeding of hummingbirds was controlled by indigenous people and the birds were sold in mercados throughout central Mexico. African practitioners and others would use the hummingbirds in rituals dealing with power or love. In ancient Mexico the hummingbird was not only the symbol of the Aztec war god Huitzilopochtli, but other ancient indigenous groups in Mexico saw the hummingbird as a representation of their local love goddess or feminine spirit. It’s interesting that the use of the hummingbird would be so important in the rituals of those of African descent who were using the birds as they had been used in Mexico for hundreds or thousands of years before African slaves arrived in the New World. Often, what was found centuries into Spain’s colonial experiment in the New World was a blending and morphing of many practices and beliefs with no one knowing where it all came from.

Inquisition’s inception in 1571 when the King of Spain declared: “That the inquisitors should never proceed against the Indians, but against the old Christians and their descendants and other persons against whom in these kingdoms of Spain it is customary to proceed.” This included Spanish peninsulares, or immigrants from Spain in the New World, as well as criollos, or Spaniards born in Mexico, and a whole host of other castes and racial classifications excluding those who identified as being indigenous or who lived in indigenous communities. Researchers have cited the overwhelming number of women of African descent who show up in the records of the Inquisition in colonial Mexico. Many enslaved people, their descendants and the offspring of those who intermarried with other ethnic groups in Mexico, continued to practice African folk medicine and traditional African magic generations removed from their African origins, and were often quizzed by the minions of the Holy Office to see if what they were doing violated church dogma. Because there was a lot of cultural diffusion during the colonial era in Mexico, it was not uncommon for people of different ethnic backgrounds to share folk religious traditions and magical practices. An example of this would be the use of hummingbirds or hummingbird bones in rituals or magic potions. In colonial Mexico, the breeding of hummingbirds was controlled by indigenous people and the birds were sold in mercados throughout central Mexico. African practitioners and others would use the hummingbirds in rituals dealing with power or love. In ancient Mexico the hummingbird was not only the symbol of the Aztec war god Huitzilopochtli, but other ancient indigenous groups in Mexico saw the hummingbird as a representation of their local love goddess or feminine spirit. It’s interesting that the use of the hummingbird would be so important in the rituals of those of African descent who were using the birds as they had been used in Mexico for hundreds or thousands of years before African slaves arrived in the New World. Often, what was found centuries into Spain’s colonial experiment in the New World was a blending and morphing of many practices and beliefs with no one knowing where it all came from.

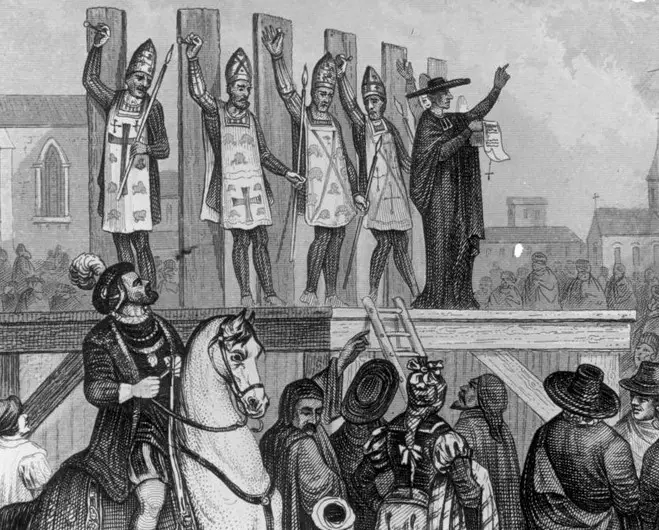

The Holy Office had a predetermined set of steps to go through to process a case. First, there was an accusation. Someone had to be accused of practicing witchcraft, entering into a pact with the Devil or otherwise going against the tenets of the Church. In late colonial Mexico, often people who engaged in activities frowned upon by the Catholic Church would “turn themselves in,” so to speak, after feeling guilt or shame and going to a priest for absolution. Depending on the severity of the transgression, the priest might deny the person confession and communion and escalate the case to the Holy Inquisition. After the accusation, the accused would be detained during which they were questioned by two inquisitors. After the detention came a trial, followed by torture of those who were found guilty as a form of punishment to occur before actual sentencing. In the most severe cases the sentencing included what was called an auto de fé, which was, essentially, an elaborate public execution, in the form of burning or strangulation, which usually took place in a major municipal plaza or town square.

Much of the thousands of documents that passed through the Office of the Holy Inquisition that survive into the 21st Century have not been properly studied, although much is known about what types of cases were being investigated by the hundreds of documents analyzed by scholars so far. Sorcery or witchcraft accusations came down more heavily on females than males, although there are records of “African witch doctors” being quizzed by the Holy Office. Women who were turned in to the Inquisition, or turned themselves in, were mostly investigated for conducting magic intended to control men. Magic potions to ensnare a desired man or spells used to keep a man from cheating were commonly used among female magical practitioners. Occasionally, women would make pacts with the Devil, but this was the overwhelming behavior of men. In colonial Mexico the Devil was not seen by many as a hideous and frightening creature, but as an entity to call upon to offer comfort, hope and sometimes just conversation. Men would make pacts with him to obtain riches, love or social status, and these pacts would oftentimes be actual documents written on parchment deeding the person’s soul to the Devil in exchange for some earthly promise. In many cases, as noted by the Holy Office, the Devil actually delivered. Invoking the power of the Devil and using folk magic in colonial Mexico has its equivalents in modern Mexico. Sometimes out of sheer desperation, the colonials were turning to alternatives to the Catholic Church that they perceived were more powerful than the traditional church. They only deferred to the Devil or some African-based magical practice because they thought the church had failed them. There are modern-day parallels in Mexico today with the worship of folk saints like the Santa Muerte or Jesus Malverde, and the turning to folk magicians or alternative beliefs because of the perceived inability of the Catholic Church to meet a person’s spiritual needs.

Much of the thousands of documents that passed through the Office of the Holy Inquisition that survive into the 21st Century have not been properly studied, although much is known about what types of cases were being investigated by the hundreds of documents analyzed by scholars so far. Sorcery or witchcraft accusations came down more heavily on females than males, although there are records of “African witch doctors” being quizzed by the Holy Office. Women who were turned in to the Inquisition, or turned themselves in, were mostly investigated for conducting magic intended to control men. Magic potions to ensnare a desired man or spells used to keep a man from cheating were commonly used among female magical practitioners. Occasionally, women would make pacts with the Devil, but this was the overwhelming behavior of men. In colonial Mexico the Devil was not seen by many as a hideous and frightening creature, but as an entity to call upon to offer comfort, hope and sometimes just conversation. Men would make pacts with him to obtain riches, love or social status, and these pacts would oftentimes be actual documents written on parchment deeding the person’s soul to the Devil in exchange for some earthly promise. In many cases, as noted by the Holy Office, the Devil actually delivered. Invoking the power of the Devil and using folk magic in colonial Mexico has its equivalents in modern Mexico. Sometimes out of sheer desperation, the colonials were turning to alternatives to the Catholic Church that they perceived were more powerful than the traditional church. They only deferred to the Devil or some African-based magical practice because they thought the church had failed them. There are modern-day parallels in Mexico today with the worship of folk saints like the Santa Muerte or Jesus Malverde, and the turning to folk magicians or alternative beliefs because of the perceived inability of the Catholic Church to meet a person’s spiritual needs.

The two sample cases from late colonial Mexico that we will examine have to do with two women accused of witchcraft and a man who made a pact with the Devil.

The first case involves two women, Isabel de Tovar and her godmother Agustina de Lara. Isabel turned herself in to the Office of the Holy Inquisition in Mexico City in February of 1709 and also turned in her godmother, both for engaging in what the inquisitors called “superstitious acts.” The older woman, Agustina, was known as a midwife and healer, and often would engage in magical practices based on folk beliefs in her healing profession. The story begins eleven years before Isabel turned herself in when she  had an illicit affair that went wrong and she wanted to get her man back. She lamented this fact to her godmother Agustina and the godmother told Isabel that she would connect her with a friend of hers, and older Afro-Mexican man named Tata Nicolás who would provide the perfect remedy for her. Tata Nicolás asked Isabel for a few of her hairs, a lump of sugar and 3 reales for payment. After a few days, young Isabel went to the modest home of Tata Nicolás to see what he had for her. The old practitioner gave her a foul-smelling yellow powder wrapped in paper and told Isabel to smear some of it on her lover’s clothes or body and keep the rest of the powder on her person. Researchers believe that the powder was most likely a derivative from the puyomate, a leafy plant that had been cultivated by the ancient indigenous peoples of central Mexico for untold centuries. Tata Nicolás also gave back to Isabel the lump of sugar she originally gave him, and she was supposed to sprinkle it on the man’s food, as it was now infused with supernatural powers. Isabel attempted to smear the foul-smelling powder on the shirtsleeves of her male paramour, but he protested and left her. Isabel had not seen Tata Nicolás or her godmother Agustina after this incident, but only a few times on the streets of Mexico City in passing. Many years later, Agustina attended Isabel’s wedding to different man and the following Christmas, Isabel spent time at Agustina’s home. During the Christmas visit, Agustina asked Isabel how her marriage was going and gave her two sticks and a powder to help keep her husband from leaving her. The sticks were strange and foul smelling and did not come from Mexico. Isabel stored the items in her house for a few days and then started to feel guilty for falling prey to such silly superstitions. She eventually burned the sticks and the powder pouch. Isabel’s guilt is what made her turn herself in to the Inquisition, along with her godmother. Poor Tata Nicolás had passed away a few years before. Had he been alive, he would have probably been involved in the case as well. Isabel received a scolding from the inquisitors for burning the sticks and powder on her own authority as the Office of the Holy Inquisition liked to examine all real evidence of magical practices. Isabel and Agustina were instructed to recite a station of the Holy Sacrament for 8 days and to report any other future superstitious activities or they would be excommunicated. No torture or burning at the stake for these two women.

had an illicit affair that went wrong and she wanted to get her man back. She lamented this fact to her godmother Agustina and the godmother told Isabel that she would connect her with a friend of hers, and older Afro-Mexican man named Tata Nicolás who would provide the perfect remedy for her. Tata Nicolás asked Isabel for a few of her hairs, a lump of sugar and 3 reales for payment. After a few days, young Isabel went to the modest home of Tata Nicolás to see what he had for her. The old practitioner gave her a foul-smelling yellow powder wrapped in paper and told Isabel to smear some of it on her lover’s clothes or body and keep the rest of the powder on her person. Researchers believe that the powder was most likely a derivative from the puyomate, a leafy plant that had been cultivated by the ancient indigenous peoples of central Mexico for untold centuries. Tata Nicolás also gave back to Isabel the lump of sugar she originally gave him, and she was supposed to sprinkle it on the man’s food, as it was now infused with supernatural powers. Isabel attempted to smear the foul-smelling powder on the shirtsleeves of her male paramour, but he protested and left her. Isabel had not seen Tata Nicolás or her godmother Agustina after this incident, but only a few times on the streets of Mexico City in passing. Many years later, Agustina attended Isabel’s wedding to different man and the following Christmas, Isabel spent time at Agustina’s home. During the Christmas visit, Agustina asked Isabel how her marriage was going and gave her two sticks and a powder to help keep her husband from leaving her. The sticks were strange and foul smelling and did not come from Mexico. Isabel stored the items in her house for a few days and then started to feel guilty for falling prey to such silly superstitions. She eventually burned the sticks and the powder pouch. Isabel’s guilt is what made her turn herself in to the Inquisition, along with her godmother. Poor Tata Nicolás had passed away a few years before. Had he been alive, he would have probably been involved in the case as well. Isabel received a scolding from the inquisitors for burning the sticks and powder on her own authority as the Office of the Holy Inquisition liked to examine all real evidence of magical practices. Isabel and Agustina were instructed to recite a station of the Holy Sacrament for 8 days and to report any other future superstitious activities or they would be excommunicated. No torture or burning at the stake for these two women.

An interesting case in the archives of the Office of the Holy Inquisition of a pact with the Devil is that of 22-year-old Juan Manuel de Rosas. Young Juan Manuel was a swashbuckling character whose debauchery and womanizing was well known in his hometown of Huehuetlán in the modern Mexican state of Puebla. Juan Manuel turned himself in to the Holy Office after speaking to traveling missionaries who were passing through his town and who encouraged him to give up his sinful ways. Juan Manuel’s missionary friar confessor later learned of his soul-selling pact with the Devil and of the tattoo of a demon that the Devil supposedly burned into the young man’s arm. Juan  Manuel’s case begins with a letter to the Holy Inquisition in Mexico City. It was written by the friar confessor asking the Holy Office how they could get back the original contract Juan Manuel had signed with the Devil and what would be the best way to remove the tattoo on his arm. The Holy Office never answered the friar’s questions, and Juan Manuel poured out several pages of testimony of his relationship with the Devil which are still available in the archives of the Inquisition. In that testimony, Juan Manuel stated that after a planned marriage fell through, he went off “screaming to all the devils,” and then, sure enough, the Devil himself appeared to him that night under a tree in the form of a monkey, speaking to him in a woman’s voice. Juan Manuel asked the Devil’s help in trying to get back his lost love, and the Prince of Darkness replied that he would need a written contract signed in blood to seal the deal. Juan Manuel then went to his friend Anastasio to get help in drawing up the contract. Anastasio himself had made a pact with the Devil to get out of prison many years before, and also credited his fine bullfighting skills to his infernal agreement, so he was the perfect person to go to. After Juan Manuel delivered the contract to the Devil, he noticed the woman he wanted to marry pass by the tree under which the Devil first appeared to him. The young man grabbed the woman, she struggled and he started to beat her, while the Devil from behind the tree urged him to sin with her and then kill her. Juan Manuel didn’t want to do that because his intention was to marry her. Confused, the young man told the woman to go back to her mother’s house. It was soon after this incident that Juan Manuel saw the light and confessed his pact with the Devil and all his other sins to the traveling friar. According to the documents, the Inquisition also wanted to speak with Anastasio, Juan Manuel’s friend who had written up the pact, but by the time the case was underway he had moved to another rancho and no one in Huehuetlán knew exactly where he was. The Holy Office absolved Juan Manuel and history knows nothing more of this man.

Manuel’s case begins with a letter to the Holy Inquisition in Mexico City. It was written by the friar confessor asking the Holy Office how they could get back the original contract Juan Manuel had signed with the Devil and what would be the best way to remove the tattoo on his arm. The Holy Office never answered the friar’s questions, and Juan Manuel poured out several pages of testimony of his relationship with the Devil which are still available in the archives of the Inquisition. In that testimony, Juan Manuel stated that after a planned marriage fell through, he went off “screaming to all the devils,” and then, sure enough, the Devil himself appeared to him that night under a tree in the form of a monkey, speaking to him in a woman’s voice. Juan Manuel asked the Devil’s help in trying to get back his lost love, and the Prince of Darkness replied that he would need a written contract signed in blood to seal the deal. Juan Manuel then went to his friend Anastasio to get help in drawing up the contract. Anastasio himself had made a pact with the Devil to get out of prison many years before, and also credited his fine bullfighting skills to his infernal agreement, so he was the perfect person to go to. After Juan Manuel delivered the contract to the Devil, he noticed the woman he wanted to marry pass by the tree under which the Devil first appeared to him. The young man grabbed the woman, she struggled and he started to beat her, while the Devil from behind the tree urged him to sin with her and then kill her. Juan Manuel didn’t want to do that because his intention was to marry her. Confused, the young man told the woman to go back to her mother’s house. It was soon after this incident that Juan Manuel saw the light and confessed his pact with the Devil and all his other sins to the traveling friar. According to the documents, the Inquisition also wanted to speak with Anastasio, Juan Manuel’s friend who had written up the pact, but by the time the case was underway he had moved to another rancho and no one in Huehuetlán knew exactly where he was. The Holy Office absolved Juan Manuel and history knows nothing more of this man.

By the early 1800s the Office of the Holy Inquisition was used by forces loyal to the king to root out possible rabble-rousing revolutionaries and political dissidents instead of heretics, witches and those who made pacts with the Devil. The once-mighty institution that maintained religious order in a new world had crumbled, and along with it so did Spain’s Empire in the Americas. By 1812 the Holy Office was abolished but brought back for political reasons a year later before being finally put to rest in 1820 on the eve of Mexican independence.

REFERENCES

Behar, Ruth. “Sex and Sin, Witchcraft and the Devil in Late-Colonial Mexico.” American Ethnologist, vol. 14, no. 1, 1987, pp. 34–54.