Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

When one needs to look up a Greek god of something it’s easy to find out. Just plug into Google, let’s say, “Who is the Greek goddess of love?” Simple: Aphrodite. The same goes for a Catholic saint. Who is the patron saint of firefighters? Easy. A quick online search tells us it’s Saint Florian. In our internet age, we want those fast and clean answers to our questions and your favorite search engines can dish up exactly what you’re looking for. It’s not so easy when talking about the deities of ancient Mexico. Some may not even call them gods and goddesses. When the Spanish first arrived in the New World and encountered living, breathing civilizations that were built upon thousands of years of culture, they tried their best to understand what they were seeing through European eyes. The early Spanish chroniclers in what would later be the nation of Mexico were educated clergy and conquistadors who tried to make sense of the complex religious beliefs of the indigenous by trying to classify and categorize things much like how we still do in the form of online search engines. Only within the past few decades have scholars begun to reexamine the ancient religions of Mesoamerica, peeling back the layers of European interpretation and trying to get to the core of what the ancient Mexicans truly believed. Their pantheon of gods was not like the Greek or Roman gods at all, although the Spanish tried to make it that way. The gods and goddesses of the ancient Mexicans were not strictly defined as we would think of gods and goddesses today. They took on different forms and served different purposes depending on location, time of year, group of people involved, need or specific situation. Recent scholars have described the gods of the Aztecs, for example, as more like avatars of ideas and beliefs personified, serving various uses as per tradition. A quick internet search of “Who was the Aztec goddess of love,” will bring back the name “Xochiquetzal.” This “goddess” or powerful feminine aspect of divine and supernatural forces was more intricate and went beyond that label for a role people wish her to play. By looking at this spiritual power called “Xochiquetzal,” we in the modern world can perhaps get a better understanding as to how the ancient Aztecs related to the divine and how they navigated their own place in this world.

When one needs to look up a Greek god of something it’s easy to find out. Just plug into Google, let’s say, “Who is the Greek goddess of love?” Simple: Aphrodite. The same goes for a Catholic saint. Who is the patron saint of firefighters? Easy. A quick online search tells us it’s Saint Florian. In our internet age, we want those fast and clean answers to our questions and your favorite search engines can dish up exactly what you’re looking for. It’s not so easy when talking about the deities of ancient Mexico. Some may not even call them gods and goddesses. When the Spanish first arrived in the New World and encountered living, breathing civilizations that were built upon thousands of years of culture, they tried their best to understand what they were seeing through European eyes. The early Spanish chroniclers in what would later be the nation of Mexico were educated clergy and conquistadors who tried to make sense of the complex religious beliefs of the indigenous by trying to classify and categorize things much like how we still do in the form of online search engines. Only within the past few decades have scholars begun to reexamine the ancient religions of Mesoamerica, peeling back the layers of European interpretation and trying to get to the core of what the ancient Mexicans truly believed. Their pantheon of gods was not like the Greek or Roman gods at all, although the Spanish tried to make it that way. The gods and goddesses of the ancient Mexicans were not strictly defined as we would think of gods and goddesses today. They took on different forms and served different purposes depending on location, time of year, group of people involved, need or specific situation. Recent scholars have described the gods of the Aztecs, for example, as more like avatars of ideas and beliefs personified, serving various uses as per tradition. A quick internet search of “Who was the Aztec goddess of love,” will bring back the name “Xochiquetzal.” This “goddess” or powerful feminine aspect of divine and supernatural forces was more intricate and went beyond that label for a role people wish her to play. By looking at this spiritual power called “Xochiquetzal,” we in the modern world can perhaps get a better understanding as to how the ancient Aztecs related to the divine and how they navigated their own place in this world.

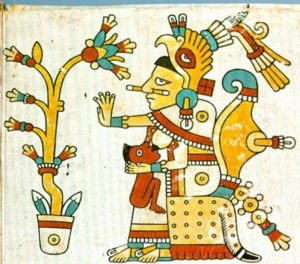

Archaeologists and other researchers believe that what is today known as the goddess Xochiquetzal originated outside the homeland of the Aztecs. When the Aztecs conquered the Tlahuica people in the cotton-growing areas of what is now the southern part of the Mexican state of Morelos, they found the people worshiping a very powerful female deity embodying all things beautiful and  pleasurable that they eventually brought back to their capital city of Tenochtitlán. This strong feminine spirit was depicted with the feathers of the quetzal bird in her hair. She was usually carrying bouquets of flowers and was always dressed in an elaborately embroidered cotton huipil. The delicate and colorful embroidery featured flowers and butterflies. The Aztecs also noted a similar goddess being worshiped on the Gulf Coast in what is now the Mexican state of Tabasco down through the Valley of Oaxaca. After she was brought back to the Aztec heartland and incorporated into the official list of the empire’s major deities and supernatural forces, the goddess was thenceforth known as Xochiquetzal, or in English, loosely translated to, “Precious Flower.” Over a short period of time, she grew in popularity and spread throughout the Aztec Empire. Although the Aztecs already had feminine aspects of the divine that they worshipped and respected before the arrival of this foreign goddess, Xochiquetzal fit in nicely with the gods, goddesses and divine aspects that they already recognized. As her popularity grew, Xochiquetzal became associated with the first woman, Tonacacihuatl, and Spanish chroniclers tried to associate her with the Biblical Eve of the Garden of Eden. According to some stories gathered at the time of the Conquest, Xochiquetzal even lived in the paradise called Tamoanchan and was cast out of it for gathering flowers from a sacred tree. For more information about this primordial ancient Mexican utopia called Tamoanchan, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 202. https://mexicounexplained.com//tamoanchan-ancient-mexican-paradise-lost/ As with many gods and goddesses and stories connected to ancient Mexican religion, there are several versions of the Xochiquetzal story, most likely based on older beliefs developing and otherwise changing over time among groups and across wide distances. In one story Xochiquetzal married a sun god called Piltzintecuhtli and they had a son named Centeotl and they lived as a happy family in the underworld. In some accounts, Centeotl is Xochiquetzal’s husband, and not her son. The rain god Tlaloc is also sometimes mentioned as her husband, or at least the husband to one of the avatars or aspects of Xochiquetzal. Many Aztec gods fell in love with her and pursued her. In another story, an aspect of Xochiquetzal known as Quetzalpetlatl, or “Feather Mat,” in English, was supposedly a real woman in historical times, and was partly responsible for the fall of the Toltec Empire. In this story she became drunk with pulque along with her brother Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl and behaved so badly that they were forced to flee the Toltec capital leaving anarchy and discord in their wake. Under a succession of Aztec rulers who wished to solidify their power and create a standardized state religion, toward the time of the Conquest the sometimes-confusing idea of Xochiquetzal became more defined and more formalized.

pleasurable that they eventually brought back to their capital city of Tenochtitlán. This strong feminine spirit was depicted with the feathers of the quetzal bird in her hair. She was usually carrying bouquets of flowers and was always dressed in an elaborately embroidered cotton huipil. The delicate and colorful embroidery featured flowers and butterflies. The Aztecs also noted a similar goddess being worshiped on the Gulf Coast in what is now the Mexican state of Tabasco down through the Valley of Oaxaca. After she was brought back to the Aztec heartland and incorporated into the official list of the empire’s major deities and supernatural forces, the goddess was thenceforth known as Xochiquetzal, or in English, loosely translated to, “Precious Flower.” Over a short period of time, she grew in popularity and spread throughout the Aztec Empire. Although the Aztecs already had feminine aspects of the divine that they worshipped and respected before the arrival of this foreign goddess, Xochiquetzal fit in nicely with the gods, goddesses and divine aspects that they already recognized. As her popularity grew, Xochiquetzal became associated with the first woman, Tonacacihuatl, and Spanish chroniclers tried to associate her with the Biblical Eve of the Garden of Eden. According to some stories gathered at the time of the Conquest, Xochiquetzal even lived in the paradise called Tamoanchan and was cast out of it for gathering flowers from a sacred tree. For more information about this primordial ancient Mexican utopia called Tamoanchan, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 202. https://mexicounexplained.com//tamoanchan-ancient-mexican-paradise-lost/ As with many gods and goddesses and stories connected to ancient Mexican religion, there are several versions of the Xochiquetzal story, most likely based on older beliefs developing and otherwise changing over time among groups and across wide distances. In one story Xochiquetzal married a sun god called Piltzintecuhtli and they had a son named Centeotl and they lived as a happy family in the underworld. In some accounts, Centeotl is Xochiquetzal’s husband, and not her son. The rain god Tlaloc is also sometimes mentioned as her husband, or at least the husband to one of the avatars or aspects of Xochiquetzal. Many Aztec gods fell in love with her and pursued her. In another story, an aspect of Xochiquetzal known as Quetzalpetlatl, or “Feather Mat,” in English, was supposedly a real woman in historical times, and was partly responsible for the fall of the Toltec Empire. In this story she became drunk with pulque along with her brother Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl and behaved so badly that they were forced to flee the Toltec capital leaving anarchy and discord in their wake. Under a succession of Aztec rulers who wished to solidify their power and create a standardized state religion, toward the time of the Conquest the sometimes-confusing idea of Xochiquetzal became more defined and more formalized.

Xochiquetzal, along with other central Mexican goddesses or feminine divine forces made up the archetypal goddess complex found in most every culture on earth. Specifically, these female forces were responsible for overseeing childbirth, fertility, erotic love, domestic production and household tasks. The Aztec religion also recognized distinctions inherent in the life cycles of women and different incarnations of Xochiquetzal took on different aspects or roles in the female life cycle. When emphasizing sensual femininity, Xochiquetzal would be personified as a young, attractive woman, usually with long black hair with straight bangs cut above the brow, to signify a fertile, unmarried young woman. When emphasizing motherhood or other conditions of more mature women, Xochiquetzal would be depicted as having shorter hair with her quetzal plumes upright on the top of her head, the way Aztec matrons typically wore their hair.

Besides the quetzal feathers and the embroidered clothing mentioned earlier, in nearly all illustrations Xochiquetzal is seen with face tattoos or black face paint around her mouth. This is said to symbolize the chewing of chicle, which was almost exclusively a women’s activity in ancient Mexico. In later imperial Aztec art, Xochiquetzal is depicted wearing a quechquemitl, or triangular cape. This cape is delicately embroidered, much like her clothing was when she was the powerful goddess of the Tlahuica people. Often, her breasts show through her clothing, to emphasize her desirability as the formal Aztec goddess of love. Her beautifully woven clothing shows Xochiquetzal’s importance to weavers and overall patronage of the textile arts. Butterfly symbolism – on her clothes and sometimes seen in a butterfly nosepiece – emphasizes her role in birth and creativity. In many artistic depictions, Xochiquetzal is shown surrounded by flowers or medicinal plants. This illustrates her importance to female healers, sorceresses and midwives. When scantily clothed, Xochiquetzal served her role as the patroness of prostitutes and the ahuiani. The ahuiani were a type of highly skilled female entertainers and hostesses, known for their skills in conversation, music, dance and games who served Aztec elites and the warrior class. The Aztec ahuiani women were much like the Hetaera of ancient Greece.

Besides the quetzal feathers and the embroidered clothing mentioned earlier, in nearly all illustrations Xochiquetzal is seen with face tattoos or black face paint around her mouth. This is said to symbolize the chewing of chicle, which was almost exclusively a women’s activity in ancient Mexico. In later imperial Aztec art, Xochiquetzal is depicted wearing a quechquemitl, or triangular cape. This cape is delicately embroidered, much like her clothing was when she was the powerful goddess of the Tlahuica people. Often, her breasts show through her clothing, to emphasize her desirability as the formal Aztec goddess of love. Her beautifully woven clothing shows Xochiquetzal’s importance to weavers and overall patronage of the textile arts. Butterfly symbolism – on her clothes and sometimes seen in a butterfly nosepiece – emphasizes her role in birth and creativity. In many artistic depictions, Xochiquetzal is shown surrounded by flowers or medicinal plants. This illustrates her importance to female healers, sorceresses and midwives. When scantily clothed, Xochiquetzal served her role as the patroness of prostitutes and the ahuiani. The ahuiani were a type of highly skilled female entertainers and hostesses, known for their skills in conversation, music, dance and games who served Aztec elites and the warrior class. The Aztec ahuiani women were much like the Hetaera of ancient Greece.

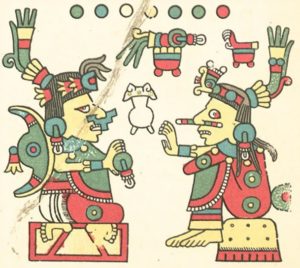

Xochiquetzal was also associated with various animals. Besides the butterflies and quetzal bird previously mentioned, the goddess was symbolized by snakes, scorpions, dogs, hummingbirds, wildcats and centipedes. Hummingbirds were used by the ancient Mexicans of many cultures as talismans for fertility. The snakes, scorpions and wildcats served as reminders of Xochiquetzal’s fierce and vicious side. In one story involving the goddess, a lord named Yappan was transformed into a scorpion after being seduced by Xochiquetzal. In her original homeland, in the modern Mexican state of Morelos, even through the 17th Century local folk healers would call on Xochiquetzal to help counteract the venom of a scorpion’s sting. In addition to the animal associations, Xochiquetzal was also associated with dwarfs and hunchbacks. The Aztecs believed that the supernatural power of Xochiquetzal could be channeled through those with severe physical deformities.

As she served an important role in the official state religion, Xochiquetzal had temples built to her throughout the Aztec Empire. Figurines made in her image have been found as far away as Guatemala showing the long-range geographical reach of her worship. The main Xochiquetzal temple of the Aztecs was located within the great Temple of Huitzilopochtli in the heart of the capital city of Tenochtitlán. There, Aztec women of higher rank could consult priestesses devoted to the goddess or could hone their skills in weaving and embroidery, sitting at the feet of master craftswomen dedicated to the arts who took up residence at the temple. Throughout the Aztec Empire, the temples of Xochiquetzal had what the Spanish called “Maidens of Penitence.” These were cloistered young women who were closely guarded by the priestesses and remained chaste and pure to serve the goddess within the confines of the temples.

As she served an important role in the official state religion, Xochiquetzal had temples built to her throughout the Aztec Empire. Figurines made in her image have been found as far away as Guatemala showing the long-range geographical reach of her worship. The main Xochiquetzal temple of the Aztecs was located within the great Temple of Huitzilopochtli in the heart of the capital city of Tenochtitlán. There, Aztec women of higher rank could consult priestesses devoted to the goddess or could hone their skills in weaving and embroidery, sitting at the feet of master craftswomen dedicated to the arts who took up residence at the temple. Throughout the Aztec Empire, the temples of Xochiquetzal had what the Spanish called “Maidens of Penitence.” These were cloistered young women who were closely guarded by the priestesses and remained chaste and pure to serve the goddess within the confines of the temples.

The ancient Aztecs had several festivals dedicated to the goddess. The main annual festival to Xochiquetzal occurred in May when the most flowers are in full bloom. A young virgin was chosen to impersonate the goddess and live like the goddess for many months before the festival. She would be symbolically married to a young warrior who was said to stand in for the god Tezcatlipoca, the “Smoking Mirror” of the night sky. During the May festival the young maiden would be sacrificed in a very gory ritual meant to appease the real goddess Xochiquetzal. During this festival people would confess their sins to clay figurines of Xochiquetzal much as a Mexican of today would do to a Catholic priest. The especially penitent would draw blood from their tongues, much like the ancient Maya used to do, and offer that blood as a sacrifice to absolve them of their bad deeds from the previous year.

There were lesser celebrations in honor of the goddess depending on location and population. Ever-present Spanish chronicler Bernardino de Sahagún witnessed an annual Xochiquetzal festival to honor prostitutes in Tlaxcala. The Franciscan priest wrote eloquently about the Xochiquetzal devotee who was the center of the festivities:

“She makes herself beautiful, she arrays herself, she is haughty. She appears like a flower, looks gaudy, arrays herself gaudily; she views herself in a mirror – carries a mirror in her hand. She bathes; she takes a sweat bath; she washes herself; she anoints herself with oils – constantly anoints herself with oils. She lives like a bathed slave, acts like a sacrificial victim; she goes about with her head high – rude, drunk, shameless – eating mushrooms. She paints her face, variously paints her face; her face is covered with rouge, her cheeks are colored, her teeth are darkened – rubbed with cochineal. Half her hair falls loose, half is wound around her head. She arranges her hair like horns.”

The Spanish priests probably did not know what to do with such an outward display of feminine power.

Known on the internet as “The Aztec Goddess of Love,” Xochiquetzal shows herself as an extraordinarily complex and influential supernatural force. As the patroness of many aspects of everything female, she played an important role in the daily lives of the Aztecs and as an official goddess of the empire she influenced the lives of untold millions throughout the vast expanse of ancient Mexico.