Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In 1882 Mexico finally settled its border dispute with Guatemala. For decades the Pacific coastal area in the extreme southeastern end of Mexico, called Soconusco, shifted between Guatemala and Mexico. The local elites favored union with Guatemala, but the central government in Mexico City had long coveted the region. After the two nations signed a peace treaty, Mexico received the lion’s share of the territory. Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz then encouraged foreign development of the area, first trying to lure Americans to Soconusco with generous offers of land and support with building infrastructure. With American interest not as he had hoped, Díaz collaborated with “The Iron Chancellor” of the newly united Germany, Otto von Bismarck, to get 450 German families to colonize Socunusco. Germany experienced high unemployment in the late 1880s and the country feared a crisis of overpopulation. Porfirio Díaz wanted cash-poor Mexico to develop the region using foreign capital. So, it was a win-win for both Germany and Mexico. With a total financing of twelve million marks provided by banks in Bremen and Hamburg, the new German settlers established vast coffee plantations carved out of the dense jungles with names such as Hamburgo, Bremen, Lübeck, Agrovia, Bismarck, Prusia, and Hanover. By the 1890s, this very fertile but remote corner of Mexico was one of the major coffee-producing regions in the world. Records show that between 1895 and 1900 these plantations exported 11.5 million kilograms of coffee. Porfirio Díaz basked in the success of his Soconusco enterprises. Little did President Díaz know that he was not the first ruler from the Valley of Mexico to enjoy the riches of this area. In fact, Profirio Díaz’ presidential offices overlooking the central square or Zocolo of Mexico City were located on the very site where the palace of the Aztec emperors once stood, where rulers also once coveted the same faraway region and later enjoyed its riches.

In 1882 Mexico finally settled its border dispute with Guatemala. For decades the Pacific coastal area in the extreme southeastern end of Mexico, called Soconusco, shifted between Guatemala and Mexico. The local elites favored union with Guatemala, but the central government in Mexico City had long coveted the region. After the two nations signed a peace treaty, Mexico received the lion’s share of the territory. Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz then encouraged foreign development of the area, first trying to lure Americans to Soconusco with generous offers of land and support with building infrastructure. With American interest not as he had hoped, Díaz collaborated with “The Iron Chancellor” of the newly united Germany, Otto von Bismarck, to get 450 German families to colonize Socunusco. Germany experienced high unemployment in the late 1880s and the country feared a crisis of overpopulation. Porfirio Díaz wanted cash-poor Mexico to develop the region using foreign capital. So, it was a win-win for both Germany and Mexico. With a total financing of twelve million marks provided by banks in Bremen and Hamburg, the new German settlers established vast coffee plantations carved out of the dense jungles with names such as Hamburgo, Bremen, Lübeck, Agrovia, Bismarck, Prusia, and Hanover. By the 1890s, this very fertile but remote corner of Mexico was one of the major coffee-producing regions in the world. Records show that between 1895 and 1900 these plantations exported 11.5 million kilograms of coffee. Porfirio Díaz basked in the success of his Soconusco enterprises. Little did President Díaz know that he was not the first ruler from the Valley of Mexico to enjoy the riches of this area. In fact, Profirio Díaz’ presidential offices overlooking the central square or Zocolo of Mexico City were located on the very site where the palace of the Aztec emperors once stood, where rulers also once coveted the same faraway region and later enjoyed its riches.

Located between the mountain range called the Sierra Madre de Chiapas and the Pacific Ocean, the territory now known as Soconusco was always an abundant area in ancient times. Known by everyone at the time of the Spanish Conquest as Xoconochco, archaeologists believe that this region is one of the oldest settled areas in all of Mesoamerica. With rich soils and great bounty from the sea to sustain large settled populations, evidence suggests that people first built small settlements in the area around 5,500 BC. Archaeologists call the culture that flourished here at the time the Chantuto and they are recognized as the very first civilization in ancient Mexico. Even though Xoconochco is hundreds of miles from the heartland of the Olmec civilization located near the cost of the Gulf of Mexico, the Olmecs first traded with the region and then established colonies there by about 1500 BC. The prize of Xoconochco was cacao. It grew abundantly there. Cacao had many uses throughout ancient Mexico. Not only was it used as a medium of exchange, it was a key ingredient in chocolate production and had ritual uses. Soon after the arrival of the Olmecs, the city of Izapa rose to prominence in the area and was one of the first sites in the region to have the monumental architecture so familiar in ancient Mesoamerican sites. Many archaeologists and historians believe that it was at Izapa, in the heart of Xoconochco, where the famous 260-day calendar was invented. This calendar would spread throughout the rest of ancient Mexico and would be later used by all major cultures from the Maya to the Aztecs. After the decline of the Olmec civilization at around 400 BC, the Xoconochco region also declined, and by 100 BC the mighty city of Izapa lay all but abandoned. Smaller regional centers sprouted up in the area and even though political entities and cultures rose and fell, the production of cacao and other luxury goods never ceased. The Xoconochco region continued to produce and export these highly prized items. The Maya, who were distant traders much as the Olmecs before them, called the region Zaklohpakab. When the Aztecs came to power in the mid-1300s in central Mexico, they took over the centuries-old trade networks connecting the Valley of Mexico to this valuable area, which was some 550 miles away. The Aztecs called this place Xoconochco because of a sour-tasting cactus that still grows on the slopes of the mountains there. In Nahuatl, the language of the ancient Aztecs, this cactus was called the xococnotchtli. As the region was very far from the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, it received very few visitors from the Aztec Empire save for the daring long-distance traders called the pochteca. For more information about this elite class of traders, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 102. https://mexicounexplained.com//pochteca-aztec-traders-aztec-spies/ The pochteca traders brought information back to the Aztec heartland along with their luxury goods. As the Aztec Empire grew, relations with Xoconochco grew more and more important.

Located between the mountain range called the Sierra Madre de Chiapas and the Pacific Ocean, the territory now known as Soconusco was always an abundant area in ancient times. Known by everyone at the time of the Spanish Conquest as Xoconochco, archaeologists believe that this region is one of the oldest settled areas in all of Mesoamerica. With rich soils and great bounty from the sea to sustain large settled populations, evidence suggests that people first built small settlements in the area around 5,500 BC. Archaeologists call the culture that flourished here at the time the Chantuto and they are recognized as the very first civilization in ancient Mexico. Even though Xoconochco is hundreds of miles from the heartland of the Olmec civilization located near the cost of the Gulf of Mexico, the Olmecs first traded with the region and then established colonies there by about 1500 BC. The prize of Xoconochco was cacao. It grew abundantly there. Cacao had many uses throughout ancient Mexico. Not only was it used as a medium of exchange, it was a key ingredient in chocolate production and had ritual uses. Soon after the arrival of the Olmecs, the city of Izapa rose to prominence in the area and was one of the first sites in the region to have the monumental architecture so familiar in ancient Mesoamerican sites. Many archaeologists and historians believe that it was at Izapa, in the heart of Xoconochco, where the famous 260-day calendar was invented. This calendar would spread throughout the rest of ancient Mexico and would be later used by all major cultures from the Maya to the Aztecs. After the decline of the Olmec civilization at around 400 BC, the Xoconochco region also declined, and by 100 BC the mighty city of Izapa lay all but abandoned. Smaller regional centers sprouted up in the area and even though political entities and cultures rose and fell, the production of cacao and other luxury goods never ceased. The Xoconochco region continued to produce and export these highly prized items. The Maya, who were distant traders much as the Olmecs before them, called the region Zaklohpakab. When the Aztecs came to power in the mid-1300s in central Mexico, they took over the centuries-old trade networks connecting the Valley of Mexico to this valuable area, which was some 550 miles away. The Aztecs called this place Xoconochco because of a sour-tasting cactus that still grows on the slopes of the mountains there. In Nahuatl, the language of the ancient Aztecs, this cactus was called the xococnotchtli. As the region was very far from the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, it received very few visitors from the Aztec Empire save for the daring long-distance traders called the pochteca. For more information about this elite class of traders, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 102. https://mexicounexplained.com//pochteca-aztec-traders-aztec-spies/ The pochteca traders brought information back to the Aztec heartland along with their luxury goods. As the Aztec Empire grew, relations with Xoconochco grew more and more important.

At the time of the Spanish Conquest the vast Aztec Empire consisted of a patchwork of subjugated peoples, colonies, conquered territories and tribute states. A map of the empire shows most of the many areas and political entities arranged in what geographers refer to as a contiguous or coterminous pattern, meaning that certain Aztec-controlled areas generally share borders with other Aztec-controlled areas. The only province not contiguous with the rest of the empire is Xoconochco. So, this province is to the rest of the Aztec Empire like what Alaska is to the “Lower 48 States.” It is still a part of the same land mass, but it is far away from the main territory of the country and is separated by lands friendly to but not controlled by the country. How did Xoconochco come to be an integral part of the Aztec Empire but remain so far away? The answer is simple: Emperor Ahuízotl.

The eighth ruler of the Aztec Empire, Ahuízotl, took his name from the fierce legendary creature which lived in Lake Texcoco, the body of water surrounding the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. For more information about that mythical lake monster, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 89. https://mexicounexplained.com//tales-mexican-lake-monsters/ From the time Emperor Ahuízotl acceded to the throne as a teenager in 1486, he lived up to his name and was one of the strongest military leaders in the history of ancient Mexico. Under his rule the Aztec Empire grew tremendously, expanding its influence and territory. Ahuízotl conquered the Mixtec and Zapotec peoples and brutally suppressed a rebellion by the Huastecs on the northern fringes of his realm. In addition to increasing the Aztec Empire’s land area and population of subjugated peoples, Ahuízotl made dramatic improvements to the Aztec capital’s civic-ceremonial center. This included an expansion of Tenochtitlán’s Great Pyramid, known today as the Templo Mayor. Although far from the heart of the Aztec Empire, the elites of the Xoconochco region were impressed with the exploits of the young and vibrant emperor. Some members of these elite families sent word through the trading networks of a desire to have a closer alliance with Tenochtitlán. Those sympathetic to the Aztecs wanted the empire’s assistance with battling competitors to the north and east in what is now the lands occupied by Guatemala and Honduras. A secret deal was hashed out which guaranteed that if the Aztecs would help them, the people of Xoconochco would become loyal subjects of the empire and would aid the Aztec military in conquering vast lands to the north and east, thus increasing total Aztec territory by about 25%. To the ambitious and successful Emperor Ahuízotl, this was a fantastic idea, especially since, according to one early Spanish chronicler, the emperor once declared, “In time, we the Aztecs will conquer the entire world.” Ahuízotl immediately dispatched a large military contingent to Xoconochco to establish a garrison there, to be followed up by Aztec government bureaucrats and eventually colonists from central Mexico. History does not record any of the details, but the powerful alliance between the Xoconochco elite families and the Aztec Empire may have never really happened. No one knows if there was a legitimate campaign to conquer Guatemala or Honduras, or whether it

The eighth ruler of the Aztec Empire, Ahuízotl, took his name from the fierce legendary creature which lived in Lake Texcoco, the body of water surrounding the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. For more information about that mythical lake monster, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 89. https://mexicounexplained.com//tales-mexican-lake-monsters/ From the time Emperor Ahuízotl acceded to the throne as a teenager in 1486, he lived up to his name and was one of the strongest military leaders in the history of ancient Mexico. Under his rule the Aztec Empire grew tremendously, expanding its influence and territory. Ahuízotl conquered the Mixtec and Zapotec peoples and brutally suppressed a rebellion by the Huastecs on the northern fringes of his realm. In addition to increasing the Aztec Empire’s land area and population of subjugated peoples, Ahuízotl made dramatic improvements to the Aztec capital’s civic-ceremonial center. This included an expansion of Tenochtitlán’s Great Pyramid, known today as the Templo Mayor. Although far from the heart of the Aztec Empire, the elites of the Xoconochco region were impressed with the exploits of the young and vibrant emperor. Some members of these elite families sent word through the trading networks of a desire to have a closer alliance with Tenochtitlán. Those sympathetic to the Aztecs wanted the empire’s assistance with battling competitors to the north and east in what is now the lands occupied by Guatemala and Honduras. A secret deal was hashed out which guaranteed that if the Aztecs would help them, the people of Xoconochco would become loyal subjects of the empire and would aid the Aztec military in conquering vast lands to the north and east, thus increasing total Aztec territory by about 25%. To the ambitious and successful Emperor Ahuízotl, this was a fantastic idea, especially since, according to one early Spanish chronicler, the emperor once declared, “In time, we the Aztecs will conquer the entire world.” Ahuízotl immediately dispatched a large military contingent to Xoconochco to establish a garrison there, to be followed up by Aztec government bureaucrats and eventually colonists from central Mexico. History does not record any of the details, but the powerful alliance between the Xoconochco elite families and the Aztec Empire may have never really happened. No one knows if there was a legitimate campaign to conquer Guatemala or Honduras, or whether it  just failed and the Aztecs and their local Xoconochco allies were defeated. There are three pre-Hispanic sources that indicate that Xoconochco became something a little more than a tribute state within the Aztec Empire. One of the sources is the Codex Mendoza. It indicates that the Aztecs established a distinct town called Xoconochco to administer the province of the same name. Two high-ranking officials from Tenochtitlán were stationed in the town of Xoconochco along with members of the military garrison. One can only guess the involvement of the region’s local elites in the Aztec provincial capital. Were they separate from their Aztec overlords or was their relationship more cooperative? Tribute and taxation documents exist showing an ample flow of goods back to the Aztec capital. Besides cacao, the goods included cotton clothing, exotic bird feathers, jaguar pelts and precious stones. This lasted up until the Spanish Conquest which caused a complete disruption of the old trade routes and political structures. In the final days of the Aztec Empire during the reign of Emperor Montezuma, Aztec histories note that parts of Xoconochco rebelled against imperial authority. This happened in the years 1502 and 1505. Before the Spanish ever went to the coastal area of the modern-day Mexico-Guatemala border, they knew of Xoconochco. In that magical few months’ time between when Emperor Montezuma welcomed Cortés and the Spanish overthrow of the Aztecs, the Spaniards gathered as much information as they could about the Aztecs and their world. This included general descriptions of the Aztec provinces. Dominican Friar Diego Durán mentions Xoconochco in his notes which eventually became a book called The History of the Indies of New Spain. Apparently, the province was so valuable that the 500+ mile route to get to it was very heavily guarded to ensure a consistent stream of products to the main market at Tlatelolco just north of the Aztec capital. Durán mentions nothing in his book about Xoconochco’s political structure nor does he delve into the history of the province. Perhaps Xoconochco represented a practical limit of the Aztec Empire. Maybe logistically there was no farther that they could go.

just failed and the Aztecs and their local Xoconochco allies were defeated. There are three pre-Hispanic sources that indicate that Xoconochco became something a little more than a tribute state within the Aztec Empire. One of the sources is the Codex Mendoza. It indicates that the Aztecs established a distinct town called Xoconochco to administer the province of the same name. Two high-ranking officials from Tenochtitlán were stationed in the town of Xoconochco along with members of the military garrison. One can only guess the involvement of the region’s local elites in the Aztec provincial capital. Were they separate from their Aztec overlords or was their relationship more cooperative? Tribute and taxation documents exist showing an ample flow of goods back to the Aztec capital. Besides cacao, the goods included cotton clothing, exotic bird feathers, jaguar pelts and precious stones. This lasted up until the Spanish Conquest which caused a complete disruption of the old trade routes and political structures. In the final days of the Aztec Empire during the reign of Emperor Montezuma, Aztec histories note that parts of Xoconochco rebelled against imperial authority. This happened in the years 1502 and 1505. Before the Spanish ever went to the coastal area of the modern-day Mexico-Guatemala border, they knew of Xoconochco. In that magical few months’ time between when Emperor Montezuma welcomed Cortés and the Spanish overthrow of the Aztecs, the Spaniards gathered as much information as they could about the Aztecs and their world. This included general descriptions of the Aztec provinces. Dominican Friar Diego Durán mentions Xoconochco in his notes which eventually became a book called The History of the Indies of New Spain. Apparently, the province was so valuable that the 500+ mile route to get to it was very heavily guarded to ensure a consistent stream of products to the main market at Tlatelolco just north of the Aztec capital. Durán mentions nothing in his book about Xoconochco’s political structure nor does he delve into the history of the province. Perhaps Xoconochco represented a practical limit of the Aztec Empire. Maybe logistically there was no farther that they could go.

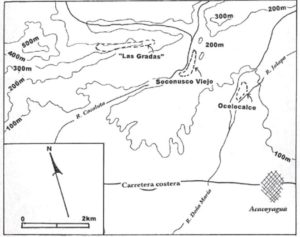

Archaeologists today are still searching for the site of the Aztec town of Xoconochco where the empire set up its military garrison. Most believe that the administrative center was located either at a site now called Soconusco Viejo or another one called Las Gradas. Soconusco Viejo is located on the northwest ridge overlooking the Cacaluta River. In addition to its early Spanish colonial ruins the site has remnants of buildings from an early 1500s indigenous settlement, including the ruins of a ballcourt. Archaeological test pits here have uncovered artifacts dating back almost 2,000 years. Very little is known about the Las Gradas site located to the north of Soconusco Viejo. Las Gradas is very strategically located, with commanding views of the coastal plain to the south and the upper Cacaluta River to the north. The river was part of an important trade route into the mountains and much traffic must have flowed through Las Gradas. Archaeological digs at Las Gradas confirm an occupation starting in the early 1500s. With its strategic location and proper date range, was there a more perfect setting for a headquarters for a newly conquered province? There is still not enough information to pin down exactly where the Aztecs set up their Xoconochco administrative center although scholarly interest is growing.

Archaeologists today are still searching for the site of the Aztec town of Xoconochco where the empire set up its military garrison. Most believe that the administrative center was located either at a site now called Soconusco Viejo or another one called Las Gradas. Soconusco Viejo is located on the northwest ridge overlooking the Cacaluta River. In addition to its early Spanish colonial ruins the site has remnants of buildings from an early 1500s indigenous settlement, including the ruins of a ballcourt. Archaeological test pits here have uncovered artifacts dating back almost 2,000 years. Very little is known about the Las Gradas site located to the north of Soconusco Viejo. Las Gradas is very strategically located, with commanding views of the coastal plain to the south and the upper Cacaluta River to the north. The river was part of an important trade route into the mountains and much traffic must have flowed through Las Gradas. Archaeological digs at Las Gradas confirm an occupation starting in the early 1500s. With its strategic location and proper date range, was there a more perfect setting for a headquarters for a newly conquered province? There is still not enough information to pin down exactly where the Aztecs set up their Xoconochco administrative center although scholarly interest is growing.

Few people know about the remotest Aztec province, whose farthest districts stretched almost 600 miles from the imperial capital of Tenochtitlán. With more attention paid to the far-flung region of Xoconochco perhaps a clearer picture of this important part of ancient Mexico will come into focus sometime soon.

REFERENCES

Berdan, Frances. “Late Postclassic Mesoamerican Trade Networks and Imperial Expansion.” In Journal of Globalization Studies, vol 8 no 1, May 2017, 14-29.

Durán, Diego. History of the Indies of New Spain. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010. Buy the book here: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0806141077/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0806141077&linkCode=as2&tag=mexicounexpla-20&linkId=ddce232284c59acd6ca188b2509c9786

Gasco, Janine. “Cacao and Commerce in Late Postclassic Xoconochco.” Rethinking the Aztec Economy, edited by Deborah L. Nichols et al., University of Arizona Press, TUCSON, 2017, pp. 221–247.