Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

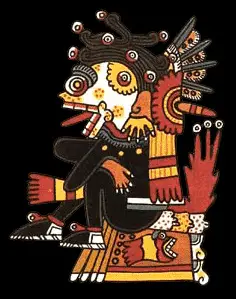

North of the Great Temple in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan stood the House of the Eagles, the headquarters of the special forces of the Aztec military known as the Eagle Knights or Eagle Warriors. Outside the entrance to this magnificent building stood two statues that frightened the Spanish conquistadors, who were invited into the Aztec capital as honored guests of the Emperor Montezuma. Now lost to history, each clay statue depicted a man with a skull for a head and an angry expression on its face. In this angry expression, the jaw jutted out slightly, so as to receive and swallow the stars at the break of dawn. The skull head was topped with a headdress made of owl feathers and paper banners. Around the necks of the statues were clay depictions of human eyeballs. Human bones from vanquished enemies served as earspools. Both sculptures had red spots on them, symbolizing spattered blood. The astonished Spaniards made note of these impressive statues in their diaries and letters home, describing them as hideous and demonic. To the residents of the imperial city, these images were beautiful. The Aztecs explained to their European guests that these larger-than-life clay figures represented the powerful Mictlantecuhtli, god of death and ruler of their underworld, called Mictlán.

North of the Great Temple in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan stood the House of the Eagles, the headquarters of the special forces of the Aztec military known as the Eagle Knights or Eagle Warriors. Outside the entrance to this magnificent building stood two statues that frightened the Spanish conquistadors, who were invited into the Aztec capital as honored guests of the Emperor Montezuma. Now lost to history, each clay statue depicted a man with a skull for a head and an angry expression on its face. In this angry expression, the jaw jutted out slightly, so as to receive and swallow the stars at the break of dawn. The skull head was topped with a headdress made of owl feathers and paper banners. Around the necks of the statues were clay depictions of human eyeballs. Human bones from vanquished enemies served as earspools. Both sculptures had red spots on them, symbolizing spattered blood. The astonished Spaniards made note of these impressive statues in their diaries and letters home, describing them as hideous and demonic. To the residents of the imperial city, these images were beautiful. The Aztecs explained to their European guests that these larger-than-life clay figures represented the powerful Mictlantecuhtli, god of death and ruler of their underworld, called Mictlán.

Mictlantecuhtli may be one of the oldest gods found throughout Mesoamerica. He has counterparts in cultures throughout ancient Mexico and existed in civilizations which predated the Aztecs. To the Zapotecs he was called Kedo. The ancient Maya called him Yum Cimil or Ah Puch. The Tarascans called him Tihuime. Art and iconography of the earlier Olmec culture suggests that they, too, had a death god similar to Mictlantecuhtli, but as they did not have a formal writing system, and hence his name is not known. By the time of the consolidation of power of the Aztecs Mictlantecuhtli’s worship had been standardized throughout the Empire and he became one of the most powerful and influential gods at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

To the Aztecs, understanding Mictlantecuhtli begins not with death, but with the story of creation. The ancient Aztecs believed that the universe had existed in previous incarnations, often referred to as “suns.” At the time of European contact, the Aztecs claimed they existed during the Fifth Sun, as there had been four previous universes or existences that had been destroyed before. The god of the underworld, Mictlantecuhtli, played a key role in the Fifth Sun, or the current reality in which the world presently exists. There are several variations to the creation of this fifth incarnation, and the general story also involves perhaps the most widely known and recognized god in ancient Mexico, Quetzalcoatl, or the Feathered Serpent. For more information on Quetzalcoatl, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 100. https://mexicounexplained.com//quetzalcoatl-man-myth-god/ In the creation story Quetzalcoatl went down to the Underworld after the destruction of the fourth sun to gather together materials to build a new 5th universe. In this new realm would live humans, and the Feathered Serpent God went down to Mictlán looking for bones of creatures from the previous world to fashion into mankind. At this time between worlds, Mictlantecuhtli lived peacefully in Mictlán in a house with no windows along with his wife Mictecacihuatl. His wife, also known as “Lady Death,” was celebrated in her own right by the Aztecs in the 9th month of the year, with those celebrations eventually forming the foundation of modern Day of the Dead observances found throughout central and southern Mexico. The Lord of Death and Lady Death lived in their windowless home with their familiars and companions: spiders, owls and bats. Mictlantecuhtli resented the presence of Quetzalcoatl in his space and decided to throw obstacles in his way to prevent him from creating humans and the new Fifth Sun. The underworld god told Quetzalcoatl that he would let him gather the bones only if he would blow a conch shell like a trumpet four times while he walked around Mictlán. Quetzalcoatl agreed, but Mictlantecuhtli tricked him by giving him a shell that would make no sound when blown into. Quetzalcoatl got around this by asking the worms and bees to help him. The worms made holes in the shell to turn it into a musical instrument and the bees buzzed inside it to give off a loud sound of a trumpet. Mictlantecuhtli conceded and told Quetzalcoatl that he could leave the underworld with the bones he needed to make humans. The feathered serpent was well on his way to leaving Mictlán when Mictlantecuhtli put up another impediment. He dug a great pit near the exit of the underworld so that Quetzalcoatl would fall into it and would not be able to leave. Sure enough, when the great god tried leaving the underworld he was spooked by a bird and fell into the pit. Mictlantecuhtli delighted in ruining Quetzalcoatl’s plans, but the feathered serpent god would not be taken down. He pulled himself out of the pit, gathered together his materials and left Mictlán to start the Fifth Sun. Once completely free of Mictlantecuhtli, Quetzalcoatl mixed his own blood with the old bones from the underworld and breathed life into humans for the first time.

To the Aztecs, understanding Mictlantecuhtli begins not with death, but with the story of creation. The ancient Aztecs believed that the universe had existed in previous incarnations, often referred to as “suns.” At the time of European contact, the Aztecs claimed they existed during the Fifth Sun, as there had been four previous universes or existences that had been destroyed before. The god of the underworld, Mictlantecuhtli, played a key role in the Fifth Sun, or the current reality in which the world presently exists. There are several variations to the creation of this fifth incarnation, and the general story also involves perhaps the most widely known and recognized god in ancient Mexico, Quetzalcoatl, or the Feathered Serpent. For more information on Quetzalcoatl, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 100. https://mexicounexplained.com//quetzalcoatl-man-myth-god/ In the creation story Quetzalcoatl went down to the Underworld after the destruction of the fourth sun to gather together materials to build a new 5th universe. In this new realm would live humans, and the Feathered Serpent God went down to Mictlán looking for bones of creatures from the previous world to fashion into mankind. At this time between worlds, Mictlantecuhtli lived peacefully in Mictlán in a house with no windows along with his wife Mictecacihuatl. His wife, also known as “Lady Death,” was celebrated in her own right by the Aztecs in the 9th month of the year, with those celebrations eventually forming the foundation of modern Day of the Dead observances found throughout central and southern Mexico. The Lord of Death and Lady Death lived in their windowless home with their familiars and companions: spiders, owls and bats. Mictlantecuhtli resented the presence of Quetzalcoatl in his space and decided to throw obstacles in his way to prevent him from creating humans and the new Fifth Sun. The underworld god told Quetzalcoatl that he would let him gather the bones only if he would blow a conch shell like a trumpet four times while he walked around Mictlán. Quetzalcoatl agreed, but Mictlantecuhtli tricked him by giving him a shell that would make no sound when blown into. Quetzalcoatl got around this by asking the worms and bees to help him. The worms made holes in the shell to turn it into a musical instrument and the bees buzzed inside it to give off a loud sound of a trumpet. Mictlantecuhtli conceded and told Quetzalcoatl that he could leave the underworld with the bones he needed to make humans. The feathered serpent was well on his way to leaving Mictlán when Mictlantecuhtli put up another impediment. He dug a great pit near the exit of the underworld so that Quetzalcoatl would fall into it and would not be able to leave. Sure enough, when the great god tried leaving the underworld he was spooked by a bird and fell into the pit. Mictlantecuhtli delighted in ruining Quetzalcoatl’s plans, but the feathered serpent god would not be taken down. He pulled himself out of the pit, gathered together his materials and left Mictlán to start the Fifth Sun. Once completely free of Mictlantecuhtli, Quetzalcoatl mixed his own blood with the old bones from the underworld and breathed life into humans for the first time.

According to the ancient Aztecs, in this new creation, this Fifth Sun, Mictlantecuhtli was an important god and took on many tasks and aspects. In the twenty day signs in the Aztec calendar, Mictlantecuhtli was the god of the day sign represented by the dog, or itzcuintli. As the god of that day, Mictlantecuhtli was responsible for supplying the souls of people born on that day. He was also responsible for supplying the souls of people born on the 6th day of the 14-day Aztec week. In the pantheon of Aztec night gods, Mictlantecuhtli was the 5th of nine gods. He took his place proudly between Centeotl, the corn god, and Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess with a skirt made of jade who presided over the waters and was the patroness of fertility and childbirth. In the 20-week cycle of the Mesoamerican calendar, Mictlantecuhtli shared the 10th week with the sun god Tonatiuh, perhaps to balance out life and death. On the clock, Mictlantecuhtli was associated with the eleventh hour of the day. He was also connected with a mythical northern region of the earth that the Aztecs called Mictlampa, a dark, cold place of eternal stillness and rest. While being associated with the northern compass direction and this barren northern region, Mictlantecuhtli is in some cases associated with the southern compass direction as well. As previously mentioned in the creation story, the Aztec god of death is often associated with owls, bats and spiders, and sometimes symbolic representations of these creatures appear in artwork connected with him.

According to the ancient Aztecs, in this new creation, this Fifth Sun, Mictlantecuhtli was an important god and took on many tasks and aspects. In the twenty day signs in the Aztec calendar, Mictlantecuhtli was the god of the day sign represented by the dog, or itzcuintli. As the god of that day, Mictlantecuhtli was responsible for supplying the souls of people born on that day. He was also responsible for supplying the souls of people born on the 6th day of the 14-day Aztec week. In the pantheon of Aztec night gods, Mictlantecuhtli was the 5th of nine gods. He took his place proudly between Centeotl, the corn god, and Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess with a skirt made of jade who presided over the waters and was the patroness of fertility and childbirth. In the 20-week cycle of the Mesoamerican calendar, Mictlantecuhtli shared the 10th week with the sun god Tonatiuh, perhaps to balance out life and death. On the clock, Mictlantecuhtli was associated with the eleventh hour of the day. He was also connected with a mythical northern region of the earth that the Aztecs called Mictlampa, a dark, cold place of eternal stillness and rest. While being associated with the northern compass direction and this barren northern region, Mictlantecuhtli is in some cases associated with the southern compass direction as well. As previously mentioned in the creation story, the Aztec god of death is often associated with owls, bats and spiders, and sometimes symbolic representations of these creatures appear in artwork connected with him.

Mictlantecuhtli’s most important function was as a death god and ruler of the underworld. The Aztecs believed that different outcomes befell the dead not dependent on any moral consequence. There was no heaven reserved for the faithful doer of good deeds and no hell for a person who led a life of wickedness and depravity. It was more important how a person died in determining where that person’s soul would end up. To warriors killed in battle or upon the stone of sacrifice, their place in the afterlife was clear: they would be escorted to the sky by the war god Huitzilopochtli to become a “companion of the eagle,” or quauhtecatl. For more information about Huitzilopochtli, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 82. https://mexicounexplained.com//war-god-aztecs-huitzilopochtli/ These fallen heroes would join the sun in the sky as it rose in the east and reached its zenith. After 4 years spent traveling across the sky, these souls would come back to earth as hummingbirds, flying from flower to flower for the rest of eternity. Those women who died in childbirth picked up where the companions of the eagle left off. Their souls resided in the heavens as well and would accompany the sun for the rest of the journey through the sky from its zenith to sunset. Those who died from drowning, in storms or in anything having to do  with water were relegated to the rain god Tlaloc after death. For more information about the Aztec god Tlaloc, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 152. https://mexicounexplained.com//tlaloc-beyond-the-rain-god/ For those killed in the unfortunate aforementioned ways, Tlaloc had a special paradise reserved for them. The place for these souls to live in eternity was called Tlalocan. When early Spanish chroniclers asked what this place was like, the Aztecs told them that it was much like the tropical lands in the eastern part of their empire. Tlaloc’s heaven was a place of unending greenery, beautiful flowers and warm rain, a gigantic garden of abundance and repose, a place of uninterrupted happiness without labor or want. While some met Huitzilopochtli after death and others met Tlaloc, these were very few people. The majority had to face the supreme god of the underworld, the bony-faced Mictlantecuhtli, and had to make the journey through the god’s kingdom, Mictlán. At the time of death, a person’s soul left the body and was joined by a small dog companion to guide him or her down into the underworld. The journey through Mictlán would last a total of four years. During that time the soul would endure many hardships and overcome many obstacles. A soul journeying through the Aztec underworld found itself running away from vicious monsters and constantly subject to icy blasts known as the “winds of obsidian.” Their last final task in Mictlán would be to cross the Nine Rivers. At the other side of the last river, a soul would just disintegrate. After all the trials of the previous four years, the exhausted spirit would reach a point of willful surrender. It simply would dissolve into the void, vanishing completely and forever.

with water were relegated to the rain god Tlaloc after death. For more information about the Aztec god Tlaloc, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 152. https://mexicounexplained.com//tlaloc-beyond-the-rain-god/ For those killed in the unfortunate aforementioned ways, Tlaloc had a special paradise reserved for them. The place for these souls to live in eternity was called Tlalocan. When early Spanish chroniclers asked what this place was like, the Aztecs told them that it was much like the tropical lands in the eastern part of their empire. Tlaloc’s heaven was a place of unending greenery, beautiful flowers and warm rain, a gigantic garden of abundance and repose, a place of uninterrupted happiness without labor or want. While some met Huitzilopochtli after death and others met Tlaloc, these were very few people. The majority had to face the supreme god of the underworld, the bony-faced Mictlantecuhtli, and had to make the journey through the god’s kingdom, Mictlán. At the time of death, a person’s soul left the body and was joined by a small dog companion to guide him or her down into the underworld. The journey through Mictlán would last a total of four years. During that time the soul would endure many hardships and overcome many obstacles. A soul journeying through the Aztec underworld found itself running away from vicious monsters and constantly subject to icy blasts known as the “winds of obsidian.” Their last final task in Mictlán would be to cross the Nine Rivers. At the other side of the last river, a soul would just disintegrate. After all the trials of the previous four years, the exhausted spirit would reach a point of willful surrender. It simply would dissolve into the void, vanishing completely and forever.

Some believe that Mictlantecuhtli didn’t quite go away after the Spanish destroyed his temples and eradicated the old Aztec religion. A contemporary Mexican folk saint called the Santa Muerte has eerie similarities with the ancient god of death. For more information about the Santa Muerte, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number nine. https://mexicounexplained.com//the-santa-muerte-death-respected/ While not tolerated by the Catholic Church and not recognized by the Vatican as an official saint, the Santa Muerte is worshiped by millions in Mexico today.  Traditional Catholics in Mexico see the devotion to the Santa Muerte as a death cult and attribute its rise in popularity to the work of demonic forces. The folk saint resembles closely the western European or euro-American image of the Grim Reaper, a hooded skeleton carrying a large sickle. Like Mictlantecuhtli, the bony-faced Santa Muerte is often accompanied by a small owl. Modern Mexicans have turned to the Santa Muerte because, as some have explained, the regular Catholic saints have failed them, and they need something more powerful to help them in dire times. One of the things that followers of the Santa Muerte pray for is what they call a “good death” and assistance in reaching the afterlife. This is similar to how the ancient Aztecs looked to Mictlantecuhtli as a guide in the death transition. It is unknown if this has been a transference of beliefs from one god to another that has happened only recently, or if these beliefs never quite died out and are now only bubbling to the surface in a more modern form. Whether related to the modern phenomenon of the Santa Muerte or not, Mictlantecuhtli is one of the most enduring and powerful gods of the Aztecs and has helped shape cultural views of death throughout Mexico carrying on to the present day.

Traditional Catholics in Mexico see the devotion to the Santa Muerte as a death cult and attribute its rise in popularity to the work of demonic forces. The folk saint resembles closely the western European or euro-American image of the Grim Reaper, a hooded skeleton carrying a large sickle. Like Mictlantecuhtli, the bony-faced Santa Muerte is often accompanied by a small owl. Modern Mexicans have turned to the Santa Muerte because, as some have explained, the regular Catholic saints have failed them, and they need something more powerful to help them in dire times. One of the things that followers of the Santa Muerte pray for is what they call a “good death” and assistance in reaching the afterlife. This is similar to how the ancient Aztecs looked to Mictlantecuhtli as a guide in the death transition. It is unknown if this has been a transference of beliefs from one god to another that has happened only recently, or if these beliefs never quite died out and are now only bubbling to the surface in a more modern form. Whether related to the modern phenomenon of the Santa Muerte or not, Mictlantecuhtli is one of the most enduring and powerful gods of the Aztecs and has helped shape cultural views of death throughout Mexico carrying on to the present day.

REFERENCES

Cartwright, Mark. “Mictlantecuhtli.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 22 Sep 2013.

Fernández, Adela. Dioses Prehispánicos de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial, 1996. (in Spanish)

Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs. Stanford: Standford University Press, 1970. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2LAPUEC