Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The modern “Drug War” in Mexico is responsible for over a hundred thousand deaths, tens of thousands of people declared “missing” and countless individuals and families ruined beyond repair. It has had a deep impact on everyday life in Mexico and has strained relations with Mexico’s neighbor to the north. While many people are very aware of aspects of the Drug War in Mexico today, many do not know that drug use in this country goes back thousands of years. As a sidebar, although the colloquial term for cannabis, marijuana, may sound Mexican, and the plant is currently cultivated in Mexico, it had its origins in Asia and not the ancient Americas. The ancient Mexicans had plenty of other substances that they were using before the arrival of the Spanish. Evidence of ancient drug use in Mexico can be found in the archaeological record, in the writings of the ancient Maya and from Spanish chroniclers who encountered intact and living indigenous civilizations.

The modern “Drug War” in Mexico is responsible for over a hundred thousand deaths, tens of thousands of people declared “missing” and countless individuals and families ruined beyond repair. It has had a deep impact on everyday life in Mexico and has strained relations with Mexico’s neighbor to the north. While many people are very aware of aspects of the Drug War in Mexico today, many do not know that drug use in this country goes back thousands of years. As a sidebar, although the colloquial term for cannabis, marijuana, may sound Mexican, and the plant is currently cultivated in Mexico, it had its origins in Asia and not the ancient Americas. The ancient Mexicans had plenty of other substances that they were using before the arrival of the Spanish. Evidence of ancient drug use in Mexico can be found in the archaeological record, in the writings of the ancient Maya and from Spanish chroniclers who encountered intact and living indigenous civilizations.

According to the Spanish medical journal Neurología, “Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures used hallucinogenic substances in magical, therapeutic, and religious rituals. These substances are considered entheogens since they were used to promote mysticism and communication with divine powers. The purpose of using these substances was to enter a trance and achieve greater enlightenment and open-mindedness. The altered state of consciousness the user aimed to reach was characterized by temporal and spatial disorientation, a sensation of ecstasy and inner peace, hallucinations of vivid colors, tendency towards introspection, and an impression of being one with nature and with the gods.”

According to the Spanish medical journal Neurología, “Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures used hallucinogenic substances in magical, therapeutic, and religious rituals. These substances are considered entheogens since they were used to promote mysticism and communication with divine powers. The purpose of using these substances was to enter a trance and achieve greater enlightenment and open-mindedness. The altered state of consciousness the user aimed to reach was characterized by temporal and spatial disorientation, a sensation of ecstasy and inner peace, hallucinations of vivid colors, tendency towards introspection, and an impression of being one with nature and with the gods.”

Drug use was often solely the domain of the shaman or priest who was an intermediary between our earthly existence and the supernatural. While it is unknown how widespread abuse of hallucinogenic substances was in ancient Mexico, it is generally assumed that the cactus, leafy plants and mushrooms harvested for their mind-altering properties were solely used for prophesy or in religious ceremonies. Complex rituals surrounding the use of these substances kept widespread use in check.

One of the oldest hallucinogens used in ancient Mexico was peyote, a type of cactus found throughout the country. Buttons of the cactus, which contain mescaline, may be chewed or brewed into a tea. The drug may induce hallucinations, altered perceptions of time and space and a feeling of weightlessness. Evidence of peyote use dates back over 5,000 years to the prehistoric period and can be found in the archaeological record, as traces of peyote have been found in ritual contexts along with ceremonial artifacts. At the time of the Spanish Conquest the survivors of the collapsed Maya civilization were still using peyote along with the indigenous people who lived in the Aztec Empire. In the 1550s, a Franciscan Friar named Bernardino de Sahagún, who was responsible for gathering native knowledge throughout the newly conquered Spanish territories in modern-day Mexico, wrote a book titled Historia de las cosas de Nueva España, or, in English, History of the Things of New Spain. In this book he describes peyote and its use:

One of the oldest hallucinogens used in ancient Mexico was peyote, a type of cactus found throughout the country. Buttons of the cactus, which contain mescaline, may be chewed or brewed into a tea. The drug may induce hallucinations, altered perceptions of time and space and a feeling of weightlessness. Evidence of peyote use dates back over 5,000 years to the prehistoric period and can be found in the archaeological record, as traces of peyote have been found in ritual contexts along with ceremonial artifacts. At the time of the Spanish Conquest the survivors of the collapsed Maya civilization were still using peyote along with the indigenous people who lived in the Aztec Empire. In the 1550s, a Franciscan Friar named Bernardino de Sahagún, who was responsible for gathering native knowledge throughout the newly conquered Spanish territories in modern-day Mexico, wrote a book titled Historia de las cosas de Nueva España, or, in English, History of the Things of New Spain. In this book he describes peyote and its use:

“There is another herb like mountain prickly pear, named peiotl, which is white and can be found in the north. Those who eat or drink of it see terrifying or absurd visions; this inebriation lasts two or three days and then subsides. It is a delicacy often enjoyed by the Chichimeca, for it is sustaining and spurs them to fight with no thought of fear, thirst, or hunger, and they say that it protects them from all danger.”

“There is another herb like mountain prickly pear, named peiotl, which is white and can be found in the north. Those who eat or drink of it see terrifying or absurd visions; this inebriation lasts two or three days and then subsides. It is a delicacy often enjoyed by the Chichimeca, for it is sustaining and spurs them to fight with no thought of fear, thirst, or hunger, and they say that it protects them from all danger.”

Soon after peyote was chronicled it was the subject of derision by Spanish authorities. Throughout New Spain its use was prohibited and its users were subjected to the Inquisition as the effects of the drug were seen as encouraging communion with the Devil or demonic forces.

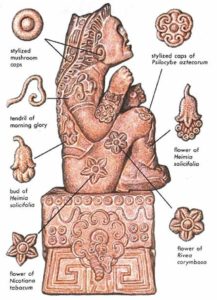

Along with peyote, the use of “sacred mushrooms” prevailed from central Mexico all the way through the Maya region of the Yucatán and dates back at least 3,500 years. We see mushrooms painted in murals at Teotihuacán, the largest urban center in Mexico 2,000 years ago. Mushrooms are depicted on various decorative items from the Maya area and in the illustrated bark books, called codices, of the ancient Maya. The ancient Mixtec people of Oaxaca had a god  named Seven Flowers always shown with magic mushrooms in his hands. The most common mushroom used was called k’aizalaj Okox by the Maya and teonanácatl by the Aztecs. In Latin, the scientific name for this fungus is Psilocybe cubensis. This mushroom was consumed fresh or ground into a powder. The effects of teonanácatl, which may last days depending on how much is consumed in one sitting, include euphoria, detachment, feelings of introspection and visual field distortion. We go back to the Spanish chronicler Sahagún for the initial European reaction to the practice of using “magic mushrooms”:

named Seven Flowers always shown with magic mushrooms in his hands. The most common mushroom used was called k’aizalaj Okox by the Maya and teonanácatl by the Aztecs. In Latin, the scientific name for this fungus is Psilocybe cubensis. This mushroom was consumed fresh or ground into a powder. The effects of teonanácatl, which may last days depending on how much is consumed in one sitting, include euphoria, detachment, feelings of introspection and visual field distortion. We go back to the Spanish chronicler Sahagún for the initial European reaction to the practice of using “magic mushrooms”:

“The little mushrooms that grow in this land are named teonanácatl. They grow beneath the hay in the fields and plains. They are round, and their stems are tall and round and slender. Their taste is unpleasant; they cause sore throat and drunkenness. They are used as medicine for fever and gout. No more than two or three should be eaten. Those who eat them see visions and feel fluttering of the heart; the visions they see are sometimes frightening and sometimes humorous. Those few who eat them in excess are driven to lust. Silly and naughty boys are told that they have eaten teonanácatl.”

In addition to the magic mushrooms and the peyote cactus, there existed a handful of different hallucinogenic plants used throughout Mexico. We will look at the three most popular ones here. From the modern-day state of Oaxaca, we find what the Mazatac people called pipiltzintli, which is a green leafy plant with white and violet-colored flowers, and a member of the sage family. It was originally confined to the shady areas of the cloud forests of the high sierras of Oaxaca and later its cultivation spread throughout Mexico. In Spanish this is called María Pastora or yerba de la pastora and its Latin scientific name is Salvia divinorum. When smoked it produces sensations of motion, uncontrollable laughter, re-living of past memories, speaking in tongues, and a feeling of overlapping realities, or bilocation, the sense of being in two places at the same time. The genus of Datura plants, called Toloache or Toloatzin by the ancient Mexicans, was once native to central Mexico and Central America but has since spread throughout the world and is cultivated primarily for its trumpeting white blossoms. The plant is highly poisonous and the seeds were used by the shamans of Mexican antiquity to induce a state of delirium, which is an inability to differentiate fantasy from reality, instead of introspective trance states or hallucinations. It produces severe pupil dilation, rapid heartrate and sometimes bizarre and violent behavior. As this plant produces highly volatile reactions, it was probably under tight

In addition to the magic mushrooms and the peyote cactus, there existed a handful of different hallucinogenic plants used throughout Mexico. We will look at the three most popular ones here. From the modern-day state of Oaxaca, we find what the Mazatac people called pipiltzintli, which is a green leafy plant with white and violet-colored flowers, and a member of the sage family. It was originally confined to the shady areas of the cloud forests of the high sierras of Oaxaca and later its cultivation spread throughout Mexico. In Spanish this is called María Pastora or yerba de la pastora and its Latin scientific name is Salvia divinorum. When smoked it produces sensations of motion, uncontrollable laughter, re-living of past memories, speaking in tongues, and a feeling of overlapping realities, or bilocation, the sense of being in two places at the same time. The genus of Datura plants, called Toloache or Toloatzin by the ancient Mexicans, was once native to central Mexico and Central America but has since spread throughout the world and is cultivated primarily for its trumpeting white blossoms. The plant is highly poisonous and the seeds were used by the shamans of Mexican antiquity to induce a state of delirium, which is an inability to differentiate fantasy from reality, instead of introspective trance states or hallucinations. It produces severe pupil dilation, rapid heartrate and sometimes bizarre and violent behavior. As this plant produces highly volatile reactions, it was probably under tight  shamanic control in ancient times. In the US we commonly call this plant Jimson Weed or Moonflower. It has many other names according to the regions in which it is found. More widespread than pipiltzintli or toloache in ancient Mexico was a type of morning glory called ololiuhqui whose Latin name is Turbina corymbosa and whose Spanish name is Flor de la virgen. This very common plant found throughout Mexico was cultivated for its round, coffee-colored seeds which contain alkaloids of the LSD family. The seeds are ground up and mixed with water. Immediately after drinking this mixture, the user experiences a psychic void and feelings of vertigo. A half hour later, the user experiences a heightened sense of euphoria and visual illusions along with changes in perceptions of reality. Ololiuhqui was used by the Maya and the Aztecs along with the Mixtecs and Zapotecs in the modern-day state of Oaxaca. Sometimes the ancient Maya would mix this plant with the bark of a tree and honey and called the drink balché. We see the recipe for this drink in the Maya holy book, the Popol Vuh. Balché was often administered as an enema. There have been several Spanish accounts of the use of Ololiuhqui. We can return to the words of the Franciscan Sahagún:

shamanic control in ancient times. In the US we commonly call this plant Jimson Weed or Moonflower. It has many other names according to the regions in which it is found. More widespread than pipiltzintli or toloache in ancient Mexico was a type of morning glory called ololiuhqui whose Latin name is Turbina corymbosa and whose Spanish name is Flor de la virgen. This very common plant found throughout Mexico was cultivated for its round, coffee-colored seeds which contain alkaloids of the LSD family. The seeds are ground up and mixed with water. Immediately after drinking this mixture, the user experiences a psychic void and feelings of vertigo. A half hour later, the user experiences a heightened sense of euphoria and visual illusions along with changes in perceptions of reality. Ololiuhqui was used by the Maya and the Aztecs along with the Mixtecs and Zapotecs in the modern-day state of Oaxaca. Sometimes the ancient Maya would mix this plant with the bark of a tree and honey and called the drink balché. We see the recipe for this drink in the Maya holy book, the Popol Vuh. Balché was often administered as an enema. There have been several Spanish accounts of the use of Ololiuhqui. We can return to the words of the Franciscan Sahagún:

“There is an herb named coatl xoxouhquij (green serpent), and it grows a seed they call ololiuqui. This seed produces inebriation and madness. People mix it in potions to give to those they wish to harm; those who eat it appear to see visions and terrifying things. Sorcerers mix it with food and drink, and so do those who hate others and wish to do them ill.”

Besides the hallucinogens already mentioned, there were many regional and lesser-known uses of plants and animals to achieve altered states. In some parts of the Maya world, for example, a certain water lily was used, in other parts of ancient Mesoamerica even the glands of certain toad species were harvested to use in potions alter reality or to commune with the gods. It seemed that wherever the Spanish went in their newly conquered territories they were finding Indians using various substances to go into trances or states of delirium or hallucination. Not appreciating the cultural or medicinal significance of what they were seeing, the Spanish were generally shocked and appalled at what they witnessed and ascribed the byproduct of the use of these natural drugs to unseen demonic forces that had to be eliminated. In a 1591 book called Problemas y secretos maravillosos de las Indias, or Problems and Marvelous Secrets of the Indies, Spanish author Juan de Cárdenas writes this:

Besides the hallucinogens already mentioned, there were many regional and lesser-known uses of plants and animals to achieve altered states. In some parts of the Maya world, for example, a certain water lily was used, in other parts of ancient Mesoamerica even the glands of certain toad species were harvested to use in potions alter reality or to commune with the gods. It seemed that wherever the Spanish went in their newly conquered territories they were finding Indians using various substances to go into trances or states of delirium or hallucination. Not appreciating the cultural or medicinal significance of what they were seeing, the Spanish were generally shocked and appalled at what they witnessed and ascribed the byproduct of the use of these natural drugs to unseen demonic forces that had to be eliminated. In a 1591 book called Problemas y secretos maravillosos de las Indias, or Problems and Marvelous Secrets of the Indies, Spanish author Juan de Cárdenas writes this:

“In sooth they tell us that peyote, and ololiuqui, when taken by mouth, will cause the wretch who takes them to lose his wits so severely that he sees the devil among other terrible and fearsome apparitions; and he will be warned (so they say) of things to come, and all this must be tricks and lies of Satan, whose nature is to deceive, with divine permission, the wretch who on such occasions seeks him”.

“In sooth they tell us that peyote, and ololiuqui, when taken by mouth, will cause the wretch who takes them to lose his wits so severely that he sees the devil among other terrible and fearsome apparitions; and he will be warned (so they say) of things to come, and all this must be tricks and lies of Satan, whose nature is to deceive, with divine permission, the wretch who on such occasions seeks him”.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

“Alucinógenos en las culturas precolumbinas mesoamericanas” article in the journal Neurología.

Various online sources

2 thoughts on “Drug Use in Ancient Mexico”

I have small statue of a girl holding a peyote button

is it aztec in origin

?