Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

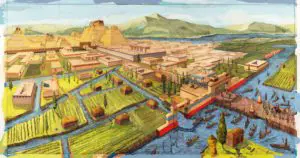

In November of 1519 a small group of Europeans led by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés entered the Aztec imperial capital of Tenochtitlán as invited guests of the Emperor Montezuma. One of the members of the Spanish party, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, wrote extensively of what he saw and experienced in the final months of the Aztec Empire. In one part of his account Díaz described the sweeping vista from the top of the main pyramid in the center of Tenochtitlán, which today sits partially restored next to the Metropolitan Cathedral in the center of Mexico City. Díaz wrote about a glistening white city on the eastern shores of Lake Texcoco along with the other marvels he saw that day. This beautiful city, which shared the name of the lake, was once the capital of an independent kingdom and at the time of the Spanish Conquest was the second-most important city in the entire Aztec Empire. Founded in the early 1300s, by a Nahua-speaking people related culturally and genetically to the Aztecs, Texcoco had grown as a trading center in its early years. After a series of complex alliances, the Texcoco Kingdom was eventually absorbed into the Aztec Empire and it was known as a center of learning throughout all ancient Mexico. In fact, the city had a vast library with hundreds of bark paper texts and scrolls from previous Mesoamerican civilizations. The rulers of the tiny kingdom patronized the arts and were known as poets and scholars. The noble house of Texcoco survived from the city’s inception through the Spanish Conquest with members of the royal line staying on as Spanish colonial administrators and advisors well into the 16th Century. Second only to the nobility of Tenochtitlán, the rulers of Texcoco lived lavish lives in a grand palace on top of the hill which dominated the city. The palace had 300 rooms, botanical and zoological collections from all over the Aztec Empire, baths with waters supplied from aqueducts and elaborate hanging gardens that bloomed year-round. To maintain their power and status as a ruling family within the ever-growing Aztec Empire, members of the noble house of Texcoco intermarried with local elites from other subjugated Mexican kingdoms and within the main royal family of the Empire. The histories of the triumphs and tragedies of this ruling house survive to this day through the Aztec and Spanish written records. Some of these histories rival modern-day Mexican telenovelas, or soap operas, with their tales of intrigue, adultery and deception, with royal luxury as a backdrop.

In November of 1519 a small group of Europeans led by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés entered the Aztec imperial capital of Tenochtitlán as invited guests of the Emperor Montezuma. One of the members of the Spanish party, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, wrote extensively of what he saw and experienced in the final months of the Aztec Empire. In one part of his account Díaz described the sweeping vista from the top of the main pyramid in the center of Tenochtitlán, which today sits partially restored next to the Metropolitan Cathedral in the center of Mexico City. Díaz wrote about a glistening white city on the eastern shores of Lake Texcoco along with the other marvels he saw that day. This beautiful city, which shared the name of the lake, was once the capital of an independent kingdom and at the time of the Spanish Conquest was the second-most important city in the entire Aztec Empire. Founded in the early 1300s, by a Nahua-speaking people related culturally and genetically to the Aztecs, Texcoco had grown as a trading center in its early years. After a series of complex alliances, the Texcoco Kingdom was eventually absorbed into the Aztec Empire and it was known as a center of learning throughout all ancient Mexico. In fact, the city had a vast library with hundreds of bark paper texts and scrolls from previous Mesoamerican civilizations. The rulers of the tiny kingdom patronized the arts and were known as poets and scholars. The noble house of Texcoco survived from the city’s inception through the Spanish Conquest with members of the royal line staying on as Spanish colonial administrators and advisors well into the 16th Century. Second only to the nobility of Tenochtitlán, the rulers of Texcoco lived lavish lives in a grand palace on top of the hill which dominated the city. The palace had 300 rooms, botanical and zoological collections from all over the Aztec Empire, baths with waters supplied from aqueducts and elaborate hanging gardens that bloomed year-round. To maintain their power and status as a ruling family within the ever-growing Aztec Empire, members of the noble house of Texcoco intermarried with local elites from other subjugated Mexican kingdoms and within the main royal family of the Empire. The histories of the triumphs and tragedies of this ruling house survive to this day through the Aztec and Spanish written records. Some of these histories rival modern-day Mexican telenovelas, or soap operas, with their tales of intrigue, adultery and deception, with royal luxury as a backdrop.

As with many ruling families around the world, the House of Texcoco claimed a mythical or almost supernatural beginning. The kings of the late 1300s and early 1400s claimed direct descent from the Chichimec rulers called Xolotl and Nopaltzin. Many other ancient chiefs, princes and kings of central Mexico at the time also claimed decent from these mythical rulers from the north to legitimize themselves in the eyes of the people they ruled over and to compete against neighboring rivals. By the early 1400s the Kingdom of Texcoco had grown and distinguished itself among the various political entities of Mesoamerica with trade networks extending thousands of miles from the capital city and an ever-growing territory.

As with many ruling families around the world, the House of Texcoco claimed a mythical or almost supernatural beginning. The kings of the late 1300s and early 1400s claimed direct descent from the Chichimec rulers called Xolotl and Nopaltzin. Many other ancient chiefs, princes and kings of central Mexico at the time also claimed decent from these mythical rulers from the north to legitimize themselves in the eyes of the people they ruled over and to compete against neighboring rivals. By the early 1400s the Kingdom of Texcoco had grown and distinguished itself among the various political entities of Mesoamerica with trade networks extending thousands of miles from the capital city and an ever-growing territory.

Between the years 1418 and 1428 Texcoco was ruled by a foreign king from the tiny city-state of Azcapotzalco located on the western shores of Lake Texcoco. The King of Texcoco, Ixtlixochitl the First, was deposed and killed while his son, Nezahualcoyotl, fled and gathered together forces to retake his father’s kingdom. Nezahualcoyotl received help from Itzcoatl, a prince of Tenochtitlán and the future emperor of the Aztecs. With the future emperor’s help, the House of Texcoco was restored to its previous glory with a caveat: Texcoco became an “ally” or an “associated state” within the growing Aztec Empire. While Texcoco’s status was no longer completely independent, the rulers still enjoyed the luxurious lifestyle that they had maintained for generations. Some members of the royal family did as many disconnected royals have done throughout time: they walled themselves off from the outside world and engaged in petty amusements from within their expanding palace complex. While technically a subject state of the Aztecs, Texcoco’s power and influence grew with time, as did the wealth of the royal family.

The restored poet-king Nezahualcoyotl reigned for 41 years. He engaged in grand public works projects and encouraged the flourishing of the arts in his territories. Under his supervision scholars gathered together the painted scrolls and other written materials that would make up the Mesoamerican equivalent of the Library of Alexandria. The common citizen enjoyed a high standard of living during the rule of Nezahualcoyotl and many ordinary people in the kingdom could read, write and took part in the realm’s rich intellectual life. The king, who had fought long and hard to maintain his position as a young man, had many wives and many sons who lived lives of previously unimagined abundance in the kingdom’s royal palace. When Nezahualcoyotl died in the year 1472 the wealth of his family rivalled that of the Aztec emperor’s. He left the throne to his son Nezahualpilli who was 8 years old, and Texcoco nobles who took direction from the Aztec rulers of Tenochtitlán acted as regents. When the boy king reached his majority, he married one of the daughters of Aztec Emperor Ahuizotl, who was styled “Princess of Tenochtitlán.” The princess was barely a teenager, but historical accounts describe her as incredibly spoiled and pampered, her disagreeable disposition formed by her life of exuberance at the Aztec imperial court. The marriage was considered to be a strategic alliance to blend two powerful families but it did not end well. The late Aztec-era chronicles of the House of Texcoco describe the princess and her fate.

The restored poet-king Nezahualcoyotl reigned for 41 years. He engaged in grand public works projects and encouraged the flourishing of the arts in his territories. Under his supervision scholars gathered together the painted scrolls and other written materials that would make up the Mesoamerican equivalent of the Library of Alexandria. The common citizen enjoyed a high standard of living during the rule of Nezahualcoyotl and many ordinary people in the kingdom could read, write and took part in the realm’s rich intellectual life. The king, who had fought long and hard to maintain his position as a young man, had many wives and many sons who lived lives of previously unimagined abundance in the kingdom’s royal palace. When Nezahualcoyotl died in the year 1472 the wealth of his family rivalled that of the Aztec emperor’s. He left the throne to his son Nezahualpilli who was 8 years old, and Texcoco nobles who took direction from the Aztec rulers of Tenochtitlán acted as regents. When the boy king reached his majority, he married one of the daughters of Aztec Emperor Ahuizotl, who was styled “Princess of Tenochtitlán.” The princess was barely a teenager, but historical accounts describe her as incredibly spoiled and pampered, her disagreeable disposition formed by her life of exuberance at the Aztec imperial court. The marriage was considered to be a strategic alliance to blend two powerful families but it did not end well. The late Aztec-era chronicles of the House of Texcoco describe the princess and her fate.

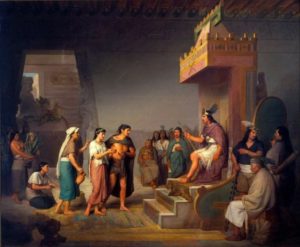

“(She) was so vicious and so devilish that if she found herself alone in her apartments and surrounded by those who served her and who, because of the splendor of her name, respected her, she would indulge in a thousand extravagances. This reached such a point that if she saw a handsome and well-shaped young man whose form agreed with her tastes and inclinations, she would give secret orders that he should enjoy her charms. When she had satisfied her desires, she would have him killed and a statue made in his likeness. She would adorn this statue with gorgeous clothes and jewels of gold and precious stones, and she would have it put in the room in which she usually passed her time. There were enough of these statues to go almost round the walls. Then the king went to see her and asked her what these statues were for, she replied that they were her gods. For his part, he believed her, knowing how religious the Aztecs were and how deeply attached to their false gods.”

The princess had a favorite young warrior whom she did not kill and fashion into a small clay statue. Instead, she saw him several times and even gave him a large jewel as a present. King Nezahualpilli heard of this gift giving and had suspected his wife’s infidelities for some time. One night he went to the princess’ private apartments to see her. The servants tried to turn away the king by telling him that the princess was sleeping, as they had done in the past. This time the king did not go away but instead barged into the princess’ bed chambers to wake her. He found nothing in the bed but a life-sized dummy made of corn-meal and straw, topped with a wig. In an adjacent room the king found his wife with three other men, as the chronicles state, “making merry.” King Nezahualpilli had the princess, her 3 paramours and a great number of accomplices, mostly female palace servants, executed in front of the royal palace. History records thousands of people coming from throughout the Aztec Empire to witness the executions. The imperial family of the Aztecs never forgave the House of Texcoco for the suffering and terrible death of the Aztec princess. While the Aztecs did not exact revenge on Texcoco for what happened, the rulers of the subjugated kingdom on the eastern shores of the lake did not have an easy time in the following years. The royal family seemed to succumb to its own drama in internal strife without the need for outside interference.

The princess had a favorite young warrior whom she did not kill and fashion into a small clay statue. Instead, she saw him several times and even gave him a large jewel as a present. King Nezahualpilli heard of this gift giving and had suspected his wife’s infidelities for some time. One night he went to the princess’ private apartments to see her. The servants tried to turn away the king by telling him that the princess was sleeping, as they had done in the past. This time the king did not go away but instead barged into the princess’ bed chambers to wake her. He found nothing in the bed but a life-sized dummy made of corn-meal and straw, topped with a wig. In an adjacent room the king found his wife with three other men, as the chronicles state, “making merry.” King Nezahualpilli had the princess, her 3 paramours and a great number of accomplices, mostly female palace servants, executed in front of the royal palace. History records thousands of people coming from throughout the Aztec Empire to witness the executions. The imperial family of the Aztecs never forgave the House of Texcoco for the suffering and terrible death of the Aztec princess. While the Aztecs did not exact revenge on Texcoco for what happened, the rulers of the subjugated kingdom on the eastern shores of the lake did not have an easy time in the following years. The royal family seemed to succumb to its own drama in internal strife without the need for outside interference.

A rising star of the Texcoco ruling house was Crown Prince Huexoctzincatzin, the eldest son of King Nezaualpilli. Around the year 1500, he was described by a contemporary Aztec writer as “an outstanding philosopher and poet, as well as having other gifts and natural graces.” The crown prince had what could be described in modern terms as an ongoing “rap battle” with the Lady of Tula, one of his father’s concubines who was popular at court and known for her great beauty and her own advanced poetic ability. According to the histories, the poetic back and forth became more intense and the prince eventually fell in love with the Lady of Tula, even making advances on her in the presence of others. The king heard of his son’s indiscretions and the matter was brought before the court. Prince Huexoctzincatzin was convicted, according to law, of treason against the king. Even though his father “loved him beyond measure,” King Nezaualpilli carried out the sentence and executed his own son. Many believed that the Lady of Tula, who was not of noble birth and the daughter of a merchant, fabricated the story of romantic indiscretions to solidify her position within the Texcoco ruling family. While she had children with the king, her sons were not in line for the throne and with the execution of the crown prince there existed a crisis of succession. In 1515, with the passing of Nezaualpilli, one of his least-favorite sons,  Cacamatzin became King of Texcoco on the orders of Aztec Emperor Montezuma. Cacamatzin proved to be a weak ruler, but loyal to the empire, and died during the Noche Triste, the fateful day in June of 1520 when the Aztecs drove the Spanish conquistadors out of Tenochtitlán and a great battle ensued. The last native ruler of Texcoco, Ixtlixochitl the Second, traded an Aztec allegiance for a Spanish one and converted to Christianity a few years after the Conquest. He changed his name to Hernán Cortés at his baptism to honor the Spanish conquistador who was his godfather. One of the last acts as king, Ixtlixochitl forced everyone in the Kingdom of Texcoco to convert to Christianity or face agonizing death. The Spanish held up the king as an example for all other native rulers in the colony of New Spain. Although stripped of their royal titles, the remaining members of the noble House of Texcoco worked with the Spanish and curried special favors and status with the new regime as they had with the old. Many of this old indigenous royal line live in the Mexico City area to this day, unaware of their family’s colorful history or its pivotal role in Mexican history.

Cacamatzin became King of Texcoco on the orders of Aztec Emperor Montezuma. Cacamatzin proved to be a weak ruler, but loyal to the empire, and died during the Noche Triste, the fateful day in June of 1520 when the Aztecs drove the Spanish conquistadors out of Tenochtitlán and a great battle ensued. The last native ruler of Texcoco, Ixtlixochitl the Second, traded an Aztec allegiance for a Spanish one and converted to Christianity a few years after the Conquest. He changed his name to Hernán Cortés at his baptism to honor the Spanish conquistador who was his godfather. One of the last acts as king, Ixtlixochitl forced everyone in the Kingdom of Texcoco to convert to Christianity or face agonizing death. The Spanish held up the king as an example for all other native rulers in the colony of New Spain. Although stripped of their royal titles, the remaining members of the noble House of Texcoco worked with the Spanish and curried special favors and status with the new regime as they had with the old. Many of this old indigenous royal line live in the Mexico City area to this day, unaware of their family’s colorful history or its pivotal role in Mexican history.

REFERENCES

Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1961.