Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In September of 2014, the Mexican Museum of Design had a curious exhibit. It was titled, “Batman a través de la creatividad mexicana“, or loosely translated into English, “Batman Expressed Through Mexican Creativity.” The show was in honor of the 75th anniversary of the comic book character Batman created by American Bob Kane. The museum, located just off the Zócalo in the heart of Mexico City, was host to 30 artists who created various renditions of Batman, from Day of the Dead themed to mariachi inspired. What stole the show, in the eyes of many was a Maya-looking piece called “Batman Camazotz” by Mérida-based artist Cristian Pacheco, who goes by the professional name of Kimbal. The official website for Kimbal says this about the artist:

In September of 2014, the Mexican Museum of Design had a curious exhibit. It was titled, “Batman a través de la creatividad mexicana“, or loosely translated into English, “Batman Expressed Through Mexican Creativity.” The show was in honor of the 75th anniversary of the comic book character Batman created by American Bob Kane. The museum, located just off the Zócalo in the heart of Mexico City, was host to 30 artists who created various renditions of Batman, from Day of the Dead themed to mariachi inspired. What stole the show, in the eyes of many was a Maya-looking piece called “Batman Camazotz” by Mérida-based artist Cristian Pacheco, who goes by the professional name of Kimbal. The official website for Kimbal says this about the artist:

“He has ventured into areas as diverse as industrial and textile design, and has participated in architecture and interior decoration projects for companies such as Daewoo, Warner, Xel-Ha and ROW Architects. The theme and aesthetics of his pieces are the result of a mixture of Mexican popular culture, with a profusion of textures and colors achieving his personal stamp.”

The internet, being what it is, has misattributed Kimbal’s modern work, and various web sites and YouTube channels are calling “Batman Camazotz” an ancient Mexican artifact representing a bat god or a god of death, and claiming that comic book artist Bob Kane got the idea for his legendary character by ripping off the work of an unknown Mesoamerican artist who lived thousands of years ago. Video gaming enthusiasts have been exposed to Camazotz in recent years through SMITE’s “Battleground of the Gods” which calls Camazotz “The Deadly God of Bats” and ascribes special abilities to him like “screeching” and unleashing vampire bats to attack his enemies. This 21st Century confusion surrounding what is known as Camazotz is nothing new. For some strange reason, this bat god, bat-man creature, or ancient supernatural dark force has been misunderstood, maligned, and misidentified ever since Europeans heard the word, “Camazotz” spoken by the K’iche Maya nearly five centuries ago.

So, who or what was Camazotz? The name comes from combining two Maya words: kame, meaning “death,” and zotz, meaning, “bat.” The first and only real authoritative source on Camazotz is the Popol Vuh. The Popol Vuh, which loosely translates to “The Book of Community” or “The Book of Counsel,” is a compilation of oral histories and religious beliefs of the K’iche Maya which existed at the time of the Spanish Conquest. The K’iche lived in what is now Guatemala and Belize, and in the Mexican states of Campeche, Chiapas, Yucatán and Quintana Roo. The first time the Popol Vuh was put into writing was in 1550, and a more detailed and elaborated work was released in the 1700s by the Spanish Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez. It’s important to note that this collection of Maya myths, stories and histories is from what archaeologists call the Post Classic Period, meaning the time in ancient Mexican history that went right up to the arrival of the Europeans. The classic civilization of the ancient Maya – most famously known for its monumental architecture, sophisticated art, and complex political organization – was long gone some 600 years before the first Spaniard set foot in the Yucatán. That 600-year gap is examined in depth in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 276 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-maya-world-between-collapse-and-conquest/ The gap of time is important because many researchers mistakenly look at the Popol Vuh and believe that every bit of it corresponds to a world existing a thousand years before. Stories change over time, languages change over time, and meanings of things change over time, so one should be careful when trying to project the contents of the Popol Vuh backward in time. The supernatural bat creature or bat god called the Camazotz is briefly mentioned in the Popol Vuh.

So, who or what was Camazotz? The name comes from combining two Maya words: kame, meaning “death,” and zotz, meaning, “bat.” The first and only real authoritative source on Camazotz is the Popol Vuh. The Popol Vuh, which loosely translates to “The Book of Community” or “The Book of Counsel,” is a compilation of oral histories and religious beliefs of the K’iche Maya which existed at the time of the Spanish Conquest. The K’iche lived in what is now Guatemala and Belize, and in the Mexican states of Campeche, Chiapas, Yucatán and Quintana Roo. The first time the Popol Vuh was put into writing was in 1550, and a more detailed and elaborated work was released in the 1700s by the Spanish Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez. It’s important to note that this collection of Maya myths, stories and histories is from what archaeologists call the Post Classic Period, meaning the time in ancient Mexican history that went right up to the arrival of the Europeans. The classic civilization of the ancient Maya – most famously known for its monumental architecture, sophisticated art, and complex political organization – was long gone some 600 years before the first Spaniard set foot in the Yucatán. That 600-year gap is examined in depth in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 276 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-maya-world-between-collapse-and-conquest/ The gap of time is important because many researchers mistakenly look at the Popol Vuh and believe that every bit of it corresponds to a world existing a thousand years before. Stories change over time, languages change over time, and meanings of things change over time, so one should be careful when trying to project the contents of the Popol Vuh backward in time. The supernatural bat creature or bat god called the Camazotz is briefly mentioned in the Popol Vuh.

In Part 4 of the text, a dark messenger with bat-like wings from the Maya underworld brokers a deal between humans and Lord Tohil, who was the K’iche Maya god of the sun and rain. At the time of Spanish contact, Lord Tohil was considered the patron of the K’iche people and their chief deity. Lord Tohil was to give humans fire in exchange for several dozen human sacrifices. The “dark messenger” who brokered the deal has been interpreted to be Camazotz although he is not mentioned by name.

The main section of the Popol Vuh dealing with Camazotz involves the Hero Twins – Hunahpu and Xbalanque – of the Maya creation story. In their adventures in Xibalba, the Maya underworld, the twins had to spend the night in the House of Bats. The boys were so terrified that they shrank themselves and hid in their blowguns to escape from the hundreds of bats swirling around them. When Hunahpu stuck his head out of his blowgun to see if the sun had risen, Camazotz tore off his head and carried it to the underworld’s ballcourt, so it could be used by the gods in the next ballgame match. For more about the Maya Hero Twins, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 85 https://mexicounexplained.com/hero-twins-maya-creation-story/ . Other than this direct interaction with the Hero Twins, there is very little else about Camazotz found in the legends and stories of the Maya at the time of the arrival of the Spanish.

The main section of the Popol Vuh dealing with Camazotz involves the Hero Twins – Hunahpu and Xbalanque – of the Maya creation story. In their adventures in Xibalba, the Maya underworld, the twins had to spend the night in the House of Bats. The boys were so terrified that they shrank themselves and hid in their blowguns to escape from the hundreds of bats swirling around them. When Hunahpu stuck his head out of his blowgun to see if the sun had risen, Camazotz tore off his head and carried it to the underworld’s ballcourt, so it could be used by the gods in the next ballgame match. For more about the Maya Hero Twins, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 85 https://mexicounexplained.com/hero-twins-maya-creation-story/ . Other than this direct interaction with the Hero Twins, there is very little else about Camazotz found in the legends and stories of the Maya at the time of the arrival of the Spanish.

As stated earlier, many archaeologists and other researchers have tried to tie this gigantic supernatural death bat to other ancient cultures in Mexico. Most Mesoamerican scholars believe that successive cultures built upon those that came before them, and there is much evidence for this in many areas of culture found throughout ancient Mexico, from architecture to the calendar systems to religious beliefs. So, it is not entirely unreasonable to project Camazotz back into time. The problem is that there is very little evidence to do so, and much of the conclusions drawn in the past have been along the lines of “make it fit.” As there has been a renewed interest in Camazotz lately, researchers have revisited some of the older conclusions and are looking at them more critically.

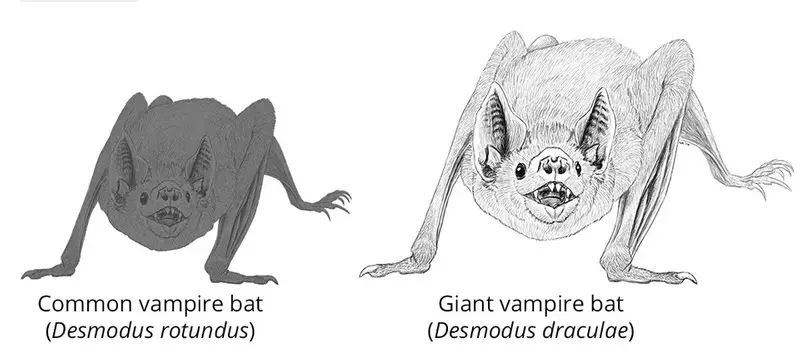

The first evidence of a large bat god in ancient Mexico comes from the discovery of the existence of a bat death cult among the Zapotecs of Oaxaca dating to around 200 AD. Could this be the foundation for the Camazotz story? It’s not known for sure. As bats are nocturnal creatures and inspire fear in most people around the world, it is not unusual for a bat to inspire stories of death and horror. Ascribing supernatural powers to creatures in the context of myth or folklore is a logical extension of their own earthly powers. Some researchers believe that the whole foundation of a death bat god may come from a more distant place in the human memory, predating the Zapotecs by thousands of years. In 1965 the skeletal remains of a very large vampire bat were discovered in the Cueva del Guáncharo, Venezuela and the remains were dated to the early Holocene period, about 11,000 years ago. The gigantic bat was christened with the scientific name Desmodus draculae and since that 1965 find more examples of this creature have been found in Argentina, Brazil, Belize, and Mexico. As this bat was rather large, it most probably went after larger prey which would have included humans. Could the Camazotz death bat story be rooted in the distant human memories of a terrifying predator that posed a grave threat to ancient Mexicans?

The first evidence of a large bat god in ancient Mexico comes from the discovery of the existence of a bat death cult among the Zapotecs of Oaxaca dating to around 200 AD. Could this be the foundation for the Camazotz story? It’s not known for sure. As bats are nocturnal creatures and inspire fear in most people around the world, it is not unusual for a bat to inspire stories of death and horror. Ascribing supernatural powers to creatures in the context of myth or folklore is a logical extension of their own earthly powers. Some researchers believe that the whole foundation of a death bat god may come from a more distant place in the human memory, predating the Zapotecs by thousands of years. In 1965 the skeletal remains of a very large vampire bat were discovered in the Cueva del Guáncharo, Venezuela and the remains were dated to the early Holocene period, about 11,000 years ago. The gigantic bat was christened with the scientific name Desmodus draculae and since that 1965 find more examples of this creature have been found in Argentina, Brazil, Belize, and Mexico. As this bat was rather large, it most probably went after larger prey which would have included humans. Could the Camazotz death bat story be rooted in the distant human memories of a terrifying predator that posed a grave threat to ancient Mexicans?

A very academic article was published in the June 2016 edition of Latin American Antiquity investigating the existence of Camazotz in the classical Maya World some 600 years before the Spanish arrived. The title of the article was Bats and the Camazotz: Correcting a Century of Mistaken Identity. Authors James E. Brady and Jeremy D. Coltman looked at depictions of bats in Maya art, specifically focusing on a vase found at a site called Chama in the late 1800s. This vase depicts a cave bat with fire coming out of its mouth and was interpreted as being the god Camazotz by the vase’s discoverer. Ever since this find, the authors contend, every bat image in Maya art, and even hints of bat imagery, have been attributed to the supposed “bat god of death,” Camazotz. The authors do raise an interesting point in their survey of the limited images of bats in ancient Maya art. In all the elaborate murals, public carvings in stone and in the few existing Maya bark paper books, there is not a single representation of the Hero Twins in the House of the Bats and their confrontation with Camazotz as described in the Popol Vuh. Perhaps the bat represented something altogether different to the ancient Maya from what was told to the European friars and investigators at the time immediately following the Spanish Conquest. Perhaps the stories changed, or different elements were added to it and subtracted from it over time. There is no reference anywhere, discovered to date, of the name “Camazotz” spelled out on any monument or in any ancient Maya written text of any kind. While bat imagery can be found here and there in the Classic Maya world, the great “Bat God of Death” is conspicuously absent. Structure 20 at the ancient Maya site of Copan is adorned with crumbling bat sculptures. Researchers in the 1990s assumed that this was the House of Bats as described in the Popol Vuh and theorized that this building served as what they called a “torture house” for political prisoners and war captives. This is a classic example of researchers “running with” a theory and making assumptions based on guesses. The building is part of the civic-ceremonial center at Copan and could have served multiple purposes. Some have theorized that Structure 20 could have served as an elite residence and the bat sculptures adorning the residence were symbols of the noble family or clan that occupied the building. Again, there are no inscriptions on the building indicating that it had anything to do with  Camazotz. In their Latin American Antiquity article, authors Brady and Coltman also noted that bats are depicted in ancient Maya art along with birds, specifically hummingbirds. To the ancient Maya, birds were seen as being messengers and hummingbirds, as pollinators, were associated with fertility. This blows apart the idea that all bat imagery in ancient Mexico had to do with death and the underworld.

Camazotz. In their Latin American Antiquity article, authors Brady and Coltman also noted that bats are depicted in ancient Maya art along with birds, specifically hummingbirds. To the ancient Maya, birds were seen as being messengers and hummingbirds, as pollinators, were associated with fertility. This blows apart the idea that all bat imagery in ancient Mexico had to do with death and the underworld.

The Aztecs of central Mexico believed in minor bat deities whose names are lost to history. In the Codex Borgia there is an illustration of an elaborate, gigantic bat creature licking the chest wounds of a sacrificial victim. In the Codex Vaticanus, a bat deity is cutting off the head of one sacrificial victim with his right hand while holding the head of another victim in his left hand. In yet another codex, a large scary bat creature is holding a human heart in one hand and a head in another. These Aztec bat representations clearly have a connection to sacrifice and possibly warfare, but any connection to the Maya world located many hundreds of miles away is very shaky. The Aztec bat images are not fully understood by researchers.

With a revived interest in Camazotz occurring in the 21st Century, there is a realization by serious scholars and researchers that very little is known about this “Bat God of Death.” Perhaps further study, more discoveries and new interpretations will flesh out this mysterious ancient deity.

REFERENCES

Benson, Elizabeth P. “The Maya and the Bat.” Latin American Indian Literatures Journal. Vol 4 (1988): 99-124.

Brady, James E., and Jeremy D. Coltman. “Bats and the Camazotz: Correcting a Century of Mistaken Identity.” Latin American Antiquity 27, no. 2 (2016): 227–37.

Emery, Kitty F. The Archaeology of Mesoamerican Animals. London: Bannerstone Press, 2009. We are Amazon affiliates. Order the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3qFi5GP