Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In step with his administration’s attempt to bolster human rights awareness, the governor of the Mexican state of Coahuila, Rubén Moreira Valdez, signed a very special decree in May of 2017. The decree proclaimed the “Tribe of Black Mascogos” to be an official indigenous people of the state of Coahuila, along with the Mexican Kikapoo discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 285: https://mexicounexplained.com/mexican-kickapoo-a-forgotten-tribe/ After being a part of Mexican society for over 150 years, the Mascogos finally received a degree of official recognition from the government in Mexico. Long marginalized and their communities neglected, Governor Valdez’ decree started the Mascogo on a path of cultural revitalization and rejuvenation that continues. The story of this unique people is now part of the state of Coahuila’s official history books.

In step with his administration’s attempt to bolster human rights awareness, the governor of the Mexican state of Coahuila, Rubén Moreira Valdez, signed a very special decree in May of 2017. The decree proclaimed the “Tribe of Black Mascogos” to be an official indigenous people of the state of Coahuila, along with the Mexican Kikapoo discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 285: https://mexicounexplained.com/mexican-kickapoo-a-forgotten-tribe/ After being a part of Mexican society for over 150 years, the Mascogos finally received a degree of official recognition from the government in Mexico. Long marginalized and their communities neglected, Governor Valdez’ decree started the Mascogo on a path of cultural revitalization and rejuvenation that continues. The story of this unique people is now part of the state of Coahuila’s official history books.

The history of the Mascogo begins some 1,300 miles away from their current homeland in the swamps and woods of north-central Florida. Spanish Florida had been a haven for escaped slaves from the north from as far back as the late 1600s. Those fleeing the sugar and cotton plantations of the Carolinas and Georgia found a new life in the wilderness of this backwater of the Spanish Empire. Sometimes the slaves would strike out on their own or join groups of other escapees living in the wilds of this mostly undeveloped colony of Spain. More frequently, though, escaped slaves would approach native villages asking for help in what was to them a strange, new land. The natives, collectively known as Seminole to outsiders, would often accept these runaways under certain conditions. For many years mainstream history books would assert that these escapees became slaves of the Seminole in exchange for shelter and safety. A modern-day reexamination of this relationship likens it more to the feudal system in medieval Europe than to the slavery of the plantations in the English colonies and later the fledgling United States. Former black slaves would be given land and assistance by the Seminole, including protection, if necessary, in exchange for a form of tribute, which may have included labor, but more often took the form of a portion of the harvest or a predetermined amount of hand-crafted goods. It was more a live-and-let live coexistence bordering on alliance between the escaped slaves and their indigenous protectors. After a few generations, there was much intermarriage between groups. Also, many former slaves and their descendants adopted elements of Seminole culture and language. By the time the Spanish sold Florida to the Americans in the early 1820s, the new overlords of the Florida Peninsula began to refer to the descendants of former slaves who lived among the natives as “The Black Seminole.” This name is still in use some 200 years later.

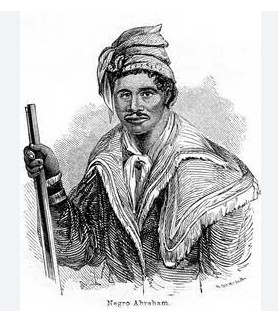

The Americans had long coveted Florida not only for territorial expansion but to take care of what they called the Indian raiding problem. Native bands from the southeastern US would cause problems for American farmers and settlers and then cross the border into Spanish territory so as not to face reprisals. Also, native groups based in Florida would cross the undefined border to wreak havoc and then retreat into the woods and swamps of their homeland. Future US president Andrew Jackson, who had long campaigned against native tribes in the southeast, became the first territorial governor of Florida. One of his first directives as governor was to order an attack on Angola, a settlement of Black Seminoles located south of Tampa Bay on the Manatee River. The Americans captured some 250 people who were taken north and sold into slavery. This attack and others led to a general uprising of natives and blacks in Florida that ended up being called the Second Seminole War by historians. Besides the raids by the US military into indigenous territory, the massive resistance ultimately had roots in the Americans’ proposed removal policy. Under this policy, Florida’s entire population of about 4,000 Seminoles and their 800 Black Seminole allies were slated to be relocated to Indian Territory in Oklahoma some 1,000 miles away. During the Second Seminole War, any Black Seminoles who were captured were immediately sold into slavery. As the war was winding down and the Americans were winning, Black Seminole leaders made a deal with the US to move to Oklahoma and remain free. This was in the year 1838. One of the leaders was known as John Horse or Juan Caballo who would later be known as the first chief of the Mascogo people in Mexico.

The Americans had long coveted Florida not only for territorial expansion but to take care of what they called the Indian raiding problem. Native bands from the southeastern US would cause problems for American farmers and settlers and then cross the border into Spanish territory so as not to face reprisals. Also, native groups based in Florida would cross the undefined border to wreak havoc and then retreat into the woods and swamps of their homeland. Future US president Andrew Jackson, who had long campaigned against native tribes in the southeast, became the first territorial governor of Florida. One of his first directives as governor was to order an attack on Angola, a settlement of Black Seminoles located south of Tampa Bay on the Manatee River. The Americans captured some 250 people who were taken north and sold into slavery. This attack and others led to a general uprising of natives and blacks in Florida that ended up being called the Second Seminole War by historians. Besides the raids by the US military into indigenous territory, the massive resistance ultimately had roots in the Americans’ proposed removal policy. Under this policy, Florida’s entire population of about 4,000 Seminoles and their 800 Black Seminole allies were slated to be relocated to Indian Territory in Oklahoma some 1,000 miles away. During the Second Seminole War, any Black Seminoles who were captured were immediately sold into slavery. As the war was winding down and the Americans were winning, Black Seminole leaders made a deal with the US to move to Oklahoma and remain free. This was in the year 1838. One of the leaders was known as John Horse or Juan Caballo who would later be known as the first chief of the Mascogo people in Mexico.

In Oklahoma the Seminole and the Black Seminole were relocated on lands under the administration of the Creek Nation. The Creek people had black slaves as agricultural workers on their lands and many times tried to enslave Black Seminoles. In addition, Black Seminoles were often targets of white American slave raiders who would capture them and forcibly take them to the plantations. Because of the continued conflict with the Creeks and the threat of kidnapping by slavers, Black Seminole leader Juan Caballo and a Seminole sub-chief named Coacoochee or “Wild Cat,” came up with a plan to leave Oklahoma. The two set their sights on lands across the Rio Grande. For Juan Caballo’s people, they didn’t have to worry about slave raiders – or so they thought – because slavery had been abolished in Mexico many years before. In Mexico, Coacoochee’s Seminoles would get out from under the domination by the Creek Nation and be away from the increasingly meddlesome US government. It should be noted here that the two came up with this solution only after Juan Caballo made two trips to Washington DC to advocate for his people. He had two simple pleas: more autonomy and security. His requests fell on deaf ears.

Going “off the reservation,” so to speak, was not an option for the Seminoles or the Black Seminoles, as their treaties with the US government confined them to their allotted lands in Oklahoma. So, Juan Caballo and Coacoochee gathered a few hundred people and left under the cover of darkness in October of 1849. It took them months to traverse Texas, evading the US Army and the Texas Rangers, who had orders to capture them and return them to Indian Territory. Along the way they also had to cross through the lands of the Comanche. It may seem strange to comprehend from 21st Century standpoints on race, but any non-Comanche traveling through Comanche territory was subject to immediate Comanche attack. It didn’t matter that half of Juan Caballo and Coacoochee’s party were natives or that the Black Seminoles were fleeing from the Comanche’s number one enemy, the US Army. These were foreigners and unwelcome in Comanche lands, no matter what the reason, even if they were just passing through. Given the dangers of the journey, the Seminole/Black Seminole exodus took the better part of a year to complete. In the summer of 1850, it was a race to the Rio Grande with the Rangers, the US Army and hostile Comanches in hot pursuit. At the springs of Las Moras, just north of the border with Mexico in Texas, the traveling party crossed paths with a familiar adversary, Major John Sprague, who had known both Juan Caballo and Coacoochee as a young man in Florida many years before and was present at their surrender. Sprague looked the other way and drank with the two rebel leaders that night, reminiscing of their days in Florida together. Before the next dawn, though, the Seminole/Black Seminole group made their final dash to the border and just in time. Someone from Major Sprague’s camp had notified the Texas Rangers and they were headed toward Las Moras to capture the group. They were too late. By the morning of July 12, 1850, Juan Caballo, Coacoochee and their followers had made it to safety across the Rio Grande. They were finally in Mexico.

Going “off the reservation,” so to speak, was not an option for the Seminoles or the Black Seminoles, as their treaties with the US government confined them to their allotted lands in Oklahoma. So, Juan Caballo and Coacoochee gathered a few hundred people and left under the cover of darkness in October of 1849. It took them months to traverse Texas, evading the US Army and the Texas Rangers, who had orders to capture them and return them to Indian Territory. Along the way they also had to cross through the lands of the Comanche. It may seem strange to comprehend from 21st Century standpoints on race, but any non-Comanche traveling through Comanche territory was subject to immediate Comanche attack. It didn’t matter that half of Juan Caballo and Coacoochee’s party were natives or that the Black Seminoles were fleeing from the Comanche’s number one enemy, the US Army. These were foreigners and unwelcome in Comanche lands, no matter what the reason, even if they were just passing through. Given the dangers of the journey, the Seminole/Black Seminole exodus took the better part of a year to complete. In the summer of 1850, it was a race to the Rio Grande with the Rangers, the US Army and hostile Comanches in hot pursuit. At the springs of Las Moras, just north of the border with Mexico in Texas, the traveling party crossed paths with a familiar adversary, Major John Sprague, who had known both Juan Caballo and Coacoochee as a young man in Florida many years before and was present at their surrender. Sprague looked the other way and drank with the two rebel leaders that night, reminiscing of their days in Florida together. Before the next dawn, though, the Seminole/Black Seminole group made their final dash to the border and just in time. Someone from Major Sprague’s camp had notified the Texas Rangers and they were headed toward Las Moras to capture the group. They were too late. By the morning of July 12, 1850, Juan Caballo, Coacoochee and their followers had made it to safety across the Rio Grande. They were finally in Mexico.

Across the Rio Grande the Mexican government welcomed them. Juan Caballo made contact with the state authorities of Coahuila and the government granted them land in exchange for a promise. The newcomers were to defend the border against Apache and Comanche raiders and any Americans who would want to cross the river to cause trouble. Juan Caballo and Coacoochee were made captains in the Mexican Army. It was soon after arriving in Mexico that the Black Seminole group got the name “Mascogo.” This is believed to have come from the word “Muscogee” which was the language of the Seminole and Creek and also sometimes used to describe the people themselves. For a few years the Mascogos had lived in a few parts of the Muzquiz Municipality of Coahuila and settled permanently in the town of El Nacimiento in 1852. Even here, slavers would cross the Rio Grande to try to abduct Mascogos to sell back into slavery in Texas, which caused some families to move further inland and deeper into Mexico. Between the time of their initial settlement and the US Civil War, the Mascogo communities of Coahuila welcomed other runaway slaves coming from  Texas. These newcomers eventually blended into Mascogo society. After the Civil War, those Seminoles who had survived smallpox returned to the US and resettled in Texas and Oklahoma, but most of the Mascogos remained in Mexico. While Coacoochee did not survive smallpox, Juan Caballo lived well into his 70s. In 1882, he rode to Mexico City to reaffirm the original Mascogo land grants which were being challenged by mestizo settlers encroaching on Mascogo lands. Juan Caballo never made it to Mexico City, though, and what happened to him along the way remains a mystery.

Texas. These newcomers eventually blended into Mascogo society. After the Civil War, those Seminoles who had survived smallpox returned to the US and resettled in Texas and Oklahoma, but most of the Mascogos remained in Mexico. While Coacoochee did not survive smallpox, Juan Caballo lived well into his 70s. In 1882, he rode to Mexico City to reaffirm the original Mascogo land grants which were being challenged by mestizo settlers encroaching on Mascogo lands. Juan Caballo never made it to Mexico City, though, and what happened to him along the way remains a mystery.

What is the 21st Century reality of the Mascogo people? Many of the descendants of the original Mascogos still retain the culture of their ancestors. This is primarily evident in food, dress, and music. The Mascogos of El Nacimento have forgotten English for the most part, but their lively songs are based in English mixed with Spanish and have West African words that no one understands. For special occasions, women will dress in a traditional way, and that includes puffy colorful dresses with aprons and large kerchiefs on their heads. Foods include sweet potato bread and boiled corn pones with the corn mashed in hollow logs with big poles the way the indigenous people of the southeastern US used to prepare cornmeal. Not surprisingly, El Nacimiento is the only town in Mexico to celebrate Juneteenth, and celebrations are low-key and not meant to draw tourists. As many Mascogos leave El Nacimento and the surrounding areas for other parts of Mexico or to the United States for work, and as many marry outside the ethnic group, there is a sense of urgency to record and preserve Mascogo culture. The Mascogo’s formal recognition by the Mexican government as a puebla indigena, or indigenous people, is a start, but with increasing pressures from the outside world, it is a race against time.

REFERENCES

Alcione M. Amos. “BLACK SEMINOLES: THE GULLAH CONNECTIONS.” The Black Scholar, vol. 41, no. 1, 2011, pp. 32–47.

Porter, Kenneth W. “The Seminole in Mexico, 1850-1861.” The Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 31, no. 1, 1951, pp. 1–36.