Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

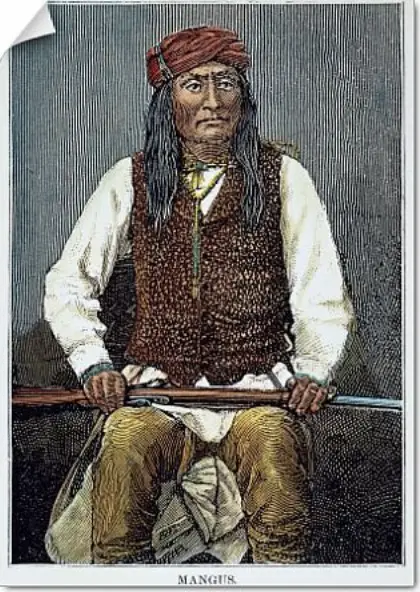

In the summer of 1847, somewhere in the mountains of Chihuahua, Apache leader Baishan, known to Mexicans as Cuchillo Negro, called a war council. Present were the chiefs of three Apache bands and their most esteemed warriors. The bands united for the first time were the Tchihende or Mimbreño, the Tsokanende or Chiricahua, and Ndendahe also known as the Mogollon. The council was called to plan a massive offensive against the Mexicans to avenge the 130 Apache killed in what historians would later call “The Galeana Massacre” which took place on July 7, 1846, in the northwestern part of Chihuahua. On that fateful day in July of 1846, under the protection of a treaty, a large group of peaceful Apache men, women and children were invited to a feast. Great quantities of mescal and whiskey were provided to the Apache guests. According to some accounts at the time, by the morning of the next day most of the Apache were in a drunken stupor. This was the perfect opportunity for an ambush. A group of Mexicans and Americans led by Irish-born James Kirker killed 130 of the unsuspecting Apache, taking their scalps for bounty, which were then put on display in Chihuahua City. The plans for revenge made during Baishan’s war council were carried out in the fall of 1847. At Baishan’s side was his lifetime friend and brother-in-law, legendary Apache chief Dasoda-Hae whose nickname in Apache was Kan-da-zis Tlishishen which translated to “Red Shirt.” To the Mexicans and later to the Americans he would be known in history as Mangas Coloradas. The two led 200 Apache warriors from the various bands on a months-long raid of destruction through northern Chihuahua. On this campaign they attacked the city of Janos and occupied the city of Ramos nearby. They burned dozens of haciendas and killed their inhabitants after stealing their livestock. They ended their mini-war on February 18, 1848 when they destroyed the mountain town of Chinapa in the state of Sonora, killing everyone except for a few whom they took as captives. This Apache crusade was one of many, and part of a larger more complex conflict that had its origins centuries before any Mexican uttered the names Cuchillo Negro or Mangas Coloradas.

In the summer of 1847, somewhere in the mountains of Chihuahua, Apache leader Baishan, known to Mexicans as Cuchillo Negro, called a war council. Present were the chiefs of three Apache bands and their most esteemed warriors. The bands united for the first time were the Tchihende or Mimbreño, the Tsokanende or Chiricahua, and Ndendahe also known as the Mogollon. The council was called to plan a massive offensive against the Mexicans to avenge the 130 Apache killed in what historians would later call “The Galeana Massacre” which took place on July 7, 1846, in the northwestern part of Chihuahua. On that fateful day in July of 1846, under the protection of a treaty, a large group of peaceful Apache men, women and children were invited to a feast. Great quantities of mescal and whiskey were provided to the Apache guests. According to some accounts at the time, by the morning of the next day most of the Apache were in a drunken stupor. This was the perfect opportunity for an ambush. A group of Mexicans and Americans led by Irish-born James Kirker killed 130 of the unsuspecting Apache, taking their scalps for bounty, which were then put on display in Chihuahua City. The plans for revenge made during Baishan’s war council were carried out in the fall of 1847. At Baishan’s side was his lifetime friend and brother-in-law, legendary Apache chief Dasoda-Hae whose nickname in Apache was Kan-da-zis Tlishishen which translated to “Red Shirt.” To the Mexicans and later to the Americans he would be known in history as Mangas Coloradas. The two led 200 Apache warriors from the various bands on a months-long raid of destruction through northern Chihuahua. On this campaign they attacked the city of Janos and occupied the city of Ramos nearby. They burned dozens of haciendas and killed their inhabitants after stealing their livestock. They ended their mini-war on February 18, 1848 when they destroyed the mountain town of Chinapa in the state of Sonora, killing everyone except for a few whom they took as captives. This Apache crusade was one of many, and part of a larger more complex conflict that had its origins centuries before any Mexican uttered the names Cuchillo Negro or Mangas Coloradas.

In early maps of New Spain there were vast, often uncharted territories in the northwestern areas simply labeled, “Apachería,” or “Land of the Apache.” The first European encounter with the Apache took place in 1541 when the Coronado Expedition reached what is now the Texas Panhandle. The Spanish called the Apache “Querechos.” A member of the expedition described these newly discovered people in his diary. Not only was the expedition member sharing with the world the first description of the Apache, but he also described North American bison or buffalo for the first time, calling them “cows.” He wrote:

“The Querechos lived in tents made of the tanned skins of the cows. They travel around near the cows killing them for food….They travel like the Arabs, with their tents and troops of dogs loaded with poles…these people eat raw flesh and drink blood. They do not eat human flesh. They are a kind people and not cruel. They are faithful friends. They are able to make themselves very well understood by means of signs. They dry the flesh in the sun, cutting it thin like a leaf, and when dry they grind it like meal to keep it and make a sort of sea soup of it to eat….They season it with fat, which they always try to secure when they kill a cow. They empty a large gut and fill it with blood, and carry this around the neck to drink when they are thirsty.”

“The Querechos lived in tents made of the tanned skins of the cows. They travel around near the cows killing them for food….They travel like the Arabs, with their tents and troops of dogs loaded with poles…these people eat raw flesh and drink blood. They do not eat human flesh. They are a kind people and not cruel. They are faithful friends. They are able to make themselves very well understood by means of signs. They dry the flesh in the sun, cutting it thin like a leaf, and when dry they grind it like meal to keep it and make a sort of sea soup of it to eat….They season it with fat, which they always try to secure when they kill a cow. They empty a large gut and fill it with blood, and carry this around the neck to drink when they are thirsty.”

Although initial Spanish contact with the Apache was extremely friendly, within a few decades their relations soured. The cause? Spaniards conducted raids on Apache camps, capturing people to sell into slavery. These Apache slaves were transported as far away as the sugar cane plantations of Chiapas, some 1,700 miles from the Apache homeland. Apache women were often sold into domestic servitude and worked for the wealthiest of families in Mexico City. The Apache resisted the raiders and retaliated by attacking fledgling Spanish settlements in what is now the American state of New Mexico. During the 1600s the Apache saw increased competition on the Great Plains from the expanding Comanche nation, and the Comanche expansion caused the Apache to move south and west, off the fertile grasslands and into rougher mountain and desert country. By the end of the 1600s some Apache bands had migrated across the Rio Grande and were present in what is now the Mexican state of Chihuahua. The loss of their buffalo hunting grounds caused many Apache groups to rely more on raiding and stealing livestock. Attacks on Spanish settlements in what was then northern New Spain intensified during the 1700s. The Spanish knew they had to come up with a more formal reaction to the ongoing and rampant Apache destruction.

The Spanish response to the Apache “problem” had three elements to it:

- Beef up the military presence in the north and construct a defensive line of presidios or forts on the frontier.

- Conduct an offensive campaign against the Apache in their own territory.

- Make peace with individual Apache bands and encourage assimilation into the mission system.

The two major presidios in the north were Janos in modern-day Chihuahua and the Presidio de San Agustín de Tucson, at the site of the modern city of Tucson, Arizona. They were links in a chain of 18 forts located about 100 miles apart and each manned by 40 to 150 soldiers. These soldiers were often supported by local militia and indigenous allies. From these defensive presidios the Spanish launched their campaigns into Apache territory. These expeditions took a great toll on both sides and were ultimately not that effective in stopping Apache raids. Some historians claim that the massive effort taken to subdue them actually emboldened the Apache to resist with an even greater intensity. In 1786, the Viceroy of New Spain, Bernardo de Gálvez, issued a formal  declaration which poured more resources and attention into the Apache situation in the north. As a captain in the Spanish army, 16 years earlier the viceroy fought the Apache alongside his Opata allies. The new 1786 viceregal declaration ramped up the war with the Apache while offering them a path to peace. Any Apache who voluntarily entered a presidio or mission was guaranteed rations and a place to live. Each Apache man was given weekly 30 liters of corn or wheat, a packet of cigarettes, a cake of brown sugar, salt, and 1/32nd of a butchered steer when available. Chiefs received more sugar and cigarettes, and women and children received a reduced amount of food. Surprisingly, this stipend system worked, and thousands of Apache entered the mission system or settled around the presidios. The number of Apache who remained nomadic or semi-sedentary is unknown. Those who did not wish to assimilate into the broader Spanish-Mestizo culture pretty much kept to themselves and lived in the remotest parts of the mountains and deserts of the north.

declaration which poured more resources and attention into the Apache situation in the north. As a captain in the Spanish army, 16 years earlier the viceroy fought the Apache alongside his Opata allies. The new 1786 viceregal declaration ramped up the war with the Apache while offering them a path to peace. Any Apache who voluntarily entered a presidio or mission was guaranteed rations and a place to live. Each Apache man was given weekly 30 liters of corn or wheat, a packet of cigarettes, a cake of brown sugar, salt, and 1/32nd of a butchered steer when available. Chiefs received more sugar and cigarettes, and women and children received a reduced amount of food. Surprisingly, this stipend system worked, and thousands of Apache entered the mission system or settled around the presidios. The number of Apache who remained nomadic or semi-sedentary is unknown. Those who did not wish to assimilate into the broader Spanish-Mestizo culture pretty much kept to themselves and lived in the remotest parts of the mountains and deserts of the north.

The Apache situation changed again with Mexican independence. The new government in Mexico City had more pressing concerns than maintaining the decades-long peace in the northern frontier. Resources to the presidios were drastically cut, including the number of soldiers stationed at each fort. The biggest blow to Apache-Mexican relations occurred some 10 years after independence in 1831 when the Mexican government cut off the guaranteed rations to the Apache who lived in and around the presidios and missions. With the loss of the stipends, the thousands of Apache who lived a settled existence just left, and regrouped in the mountains and deserts, some joining already existing bands. The Apache raids – which had all but come to a halt during the past 40 years – started up again. By October of 1831, the governor of Chihuahua declared war on the Apache and initiated a series of military campaigns against them. The national government in Mexico City was ill-prepared to fight a war with the Apache and couldn’t contain what the governor of Chihuahua had started. The skirmishes between the Apache and the Mexicans were fought exclusively in the states of Sonora and Chihuahua and involved thousands of indigenous fighters, including allies of different tribes who joined up with the Apache. Apache bands would often negotiate treaties of peace with individual municipalities, towns, or even large hacienda owners. Some Apache groups made ranch owners and town officials pay tribute to them in the form of livestock or weapons for the promise of being left alone. Another Apache band would come along, though, and not being bound by the treaties or promises of other groups or leaders, would do as they pleased. By the 1840s the situation in the north became very dire for the Mexicans, as the Apache were not the only indigenous group conducting raids and terrorizing the landed citizenry. The Comanche started crossing the Rio Grande and doing the same sorts of things on Mexican territory. For more information about the Comanche Wars, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 212: https://mexicounexplained.com/the-comanche-wars-1821-1870/

Local politicians in the north responded to the increasing Apache violence with new measures of their own. Towns and wealthy hacienda owners formed private armies, sometimes comprised of foreign mercenaries, to fight the Apache. James Kirker, the architect of the Galeana Massacre mentioned earlier, was paid 25,000 pesos by the governor of Chihuahua to raise an army of hundreds of men for the sole purpose of making war with the Apache. At the same time the Chihuahua governor increased the bounty for Apache scalps. Kirker’s army did more harm than good. In addition to the Galeana Massacre, Kirker’s forces killed many peaceful Apache who were not making war and who were involved in peace treaties with various Mexican authorities. The killing of non-warriors did not sit well in Indian Country. The Apache upped their game once again, and the raiding intensified. They would not be intimidated into submission.

Local politicians in the north responded to the increasing Apache violence with new measures of their own. Towns and wealthy hacienda owners formed private armies, sometimes comprised of foreign mercenaries, to fight the Apache. James Kirker, the architect of the Galeana Massacre mentioned earlier, was paid 25,000 pesos by the governor of Chihuahua to raise an army of hundreds of men for the sole purpose of making war with the Apache. At the same time the Chihuahua governor increased the bounty for Apache scalps. Kirker’s army did more harm than good. In addition to the Galeana Massacre, Kirker’s forces killed many peaceful Apache who were not making war and who were involved in peace treaties with various Mexican authorities. The killing of non-warriors did not sit well in Indian Country. The Apache upped their game once again, and the raiding intensified. They would not be intimidated into submission.

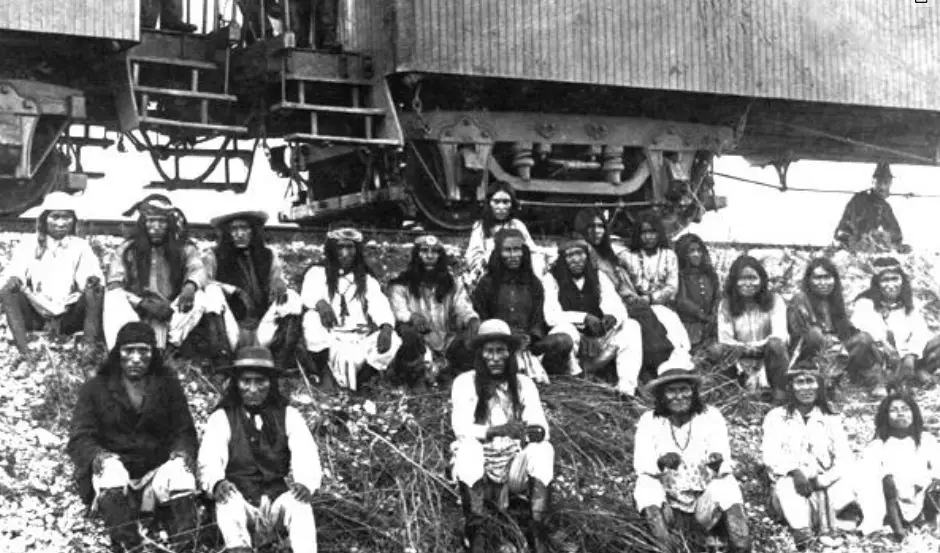

During the height of the Apache resistance an important historical event took place that would change the course of the Apache’s ongoing war with Mexico. The Mexican-American War began in 1846 and by 1848 a large part of the former Apachería was granted to the United States. The Americans took ownership of the Apache issue as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which guaranteed American protection for Mexican lives and property from cross-border Indian raids. While some Apache bands were active on the northern side of the new border and some on the southern side, the US government made lucrative deals with Apache leaders such as Mangas Coloradas and Cuchillo Negro. These two chiefs, along with a handful of other prominent Apache leaders signed a peace treaty with the United States at Fort Webster, New Mexico in 1853, never to cross the border to raid in Mexico again. Ironically, as profiled in Mexico Unexplained episode number 218 https://mexicounexplained.com/geronimo-in-mexico/ the last warring Apache to be captured in this seemingly endless series of conflicts was the famous leader Geronimo. The United States used a full one fourth of its Army to hunt down Geronimo, but they could not catch him. The Mexican government even gave permission to the US military to cross the border south to pursue this legendary warrior. Geronimo eventually surrendered to General George Crook on March 27, 1886, in the Sierra Madre of Mexico, near the Chihuahua/Sonora border and about 20 miles south of the international line, thus ending the Apache Wars.

REFERENCES

Haley, James L. Apaches: A History and Culture Portrait. Oklahoma City: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3KfWMUo

Hutton, Paul Andrew. The Apache Wars. New York: Crown Publishing, 2007. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3nzsBxJ