Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

It was another beautiful day in Mexico City. The date was Tuesday, March 4, 1947. The 33rd President of the United States, the Missouri-born Harry S Truman who was on an official state visit to Mexico, penned this in his hand-written diary:

It was another beautiful day in Mexico City. The date was Tuesday, March 4, 1947. The 33rd President of the United States, the Missouri-born Harry S Truman who was on an official state visit to Mexico, penned this in his hand-written diary:

“Tuesday morning lay a wreath on soldiers monument with lots and lots of ceremony. Then the Foreign Minister and I drive to the Chepultepec where I place a wreath on the Monument to the Ninos [sic] Heros [sic]-cadets who stood up to Old Fuss & Feathers until all but one was killed. He wraped [sic] the Mexican Flag around himself and jumped 200 feet to his death. The monument is where he fell. Had all the cadets lined up and the Foreign Minister and the Commandant of the Cadets wept-so did news men and photographers. I almost did myself. It seems that tribute to these young heros [sic] really set off the visit. They had it coming.”

After the ceremony at Chepultepec a reporter asked a very somber President Truman why he would place a wreath at a memorial to those who fought against the United States. Truman replied, “Brave men don’t belong to any one country. I respect bravery wherever I see it.”

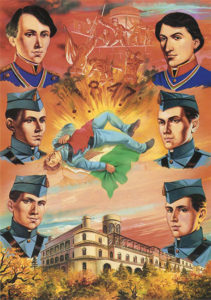

In Mexico every schoolchild knows the story of the Niños Héroes. There are streets named for the “child heroes,” also translated into English as “boy heroes” or “hero cadets.” In the late 1980s the 5,000-peso bill had the likenesses of the boys proudly displayed on the front of the note. The rarely seen modern-day 50 -peso coin honors them. There are even subway stations in Mexico City and Monterrey called “Niños Héroes.” Very few people north of the border know anything about these 6 brave cadets or the circumstances that led to their untimely deaths.

The setting for the tragic story of the Niños Héroes is one of the most beautiful vantage points in all of Mexico City. Chapultepec – or “Hill of the Grasshopper” in the Aztec language, Nahuatl – rises 200 feet above Mexico’s capital city and is now the focal point of an expansive wooded urban oasis in this metropolis of over 20 million people. In 1785 the Spanish viceroy, Bernardo de Gálvez, decided that the top of the hill would be the perfect place for a stately home and construction began on his new residence immediately. The viceroy would never occupy what amounted to the castle built on top of the “Grasshopper Hill,” however. He died right before construction ended. The property remained unoccupied for decades and in 1806 the municipality of Mexico City bought the estate on the hill but didn’t know what to do with it. What later became known as Chapultepec Castle lay abandoned until 1833 when it was converted to use as a military academy. Over a dozen years later the site would play an important role in the Mexican-American War, a conflict that seems almost lost to many modern-day Americans.

The setting for the tragic story of the Niños Héroes is one of the most beautiful vantage points in all of Mexico City. Chapultepec – or “Hill of the Grasshopper” in the Aztec language, Nahuatl – rises 200 feet above Mexico’s capital city and is now the focal point of an expansive wooded urban oasis in this metropolis of over 20 million people. In 1785 the Spanish viceroy, Bernardo de Gálvez, decided that the top of the hill would be the perfect place for a stately home and construction began on his new residence immediately. The viceroy would never occupy what amounted to the castle built on top of the “Grasshopper Hill,” however. He died right before construction ended. The property remained unoccupied for decades and in 1806 the municipality of Mexico City bought the estate on the hill but didn’t know what to do with it. What later became known as Chapultepec Castle lay abandoned until 1833 when it was converted to use as a military academy. Over a dozen years later the site would play an important role in the Mexican-American War, a conflict that seems almost lost to many modern-day Americans.

In 1846, in the wake of the American annexation of the Republic of Texas the year before, hostilities increased between the United States and Mexico. The Mexicans never recognized the independence of Texas and with the annexation came a border dispute. Both Mexico and the US claimed the land between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande and when an offer made to Mexico to purchase the disputed land was rejected, the newly elected American president, James Polk, sent Major General Zachary Taylor to occupy the disputed territory. The Mexicans burned an American fort on the Rio Grande only after they attacked Taylor’s force, killing a dozen men and capturing over 50. Two days after President Polk’s message to Congress calling for war with Mexico, the United States Congress approved the declaration of war. The date was May 23, 1846. The following year, the Americans were on the verge of capturing Mexico City. General Winfield Scott, whom President Truman referred to as Old Fuss and Feathers in his diary, approached Chapultepec Hill and saw it as a strategic prize and a key to conquering Mexico City. Scott assembled a council of war on September 11, 1847 and drew up plans to attack the hill. General Antonio López de Santa Ana commanded the Mexican Army charged with defending Mexico City against the American invasion. Santa Ana knew the importance of holding the hill but could spare no more mend to defend it than the amount that was already there. General Nicolás Bravo was in command of the forces attached to Chapultepec Hill and the amount of men under him range from 400 to 1,000, including 200 cadets, some as young as 13 years old.

At first light on September 12th, 1847, the Americans began firing artillery against Chapultepec, pounding the fortification all day until dusk. The Mexicans suffered many casualties. On the morning of September 13th General Scott ordered an infantry attack on the hill comprised of 3 assault columns. Some 500 infantrymen and marines stormed the hill. Among the Americans present were a young Captain Robert E. Lee and a young General Franklin Pierce. The Mexicans defended the hill valiantly, but a mere hour into the infantry attack General Bravo, assessing the situation as hopeless, ordered a retreat. All soldiers and cadets ceased fighting and evacuated their positions, except for 6 young cadets who would rather fight to the death than surrender. Mexican history remembers their names: Juan de la Barrera, Francisco Márquez, Agustín Melgar, Fernando Montes de Oca, Vicente Suárez and Juan Escutia.

At first light on September 12th, 1847, the Americans began firing artillery against Chapultepec, pounding the fortification all day until dusk. The Mexicans suffered many casualties. On the morning of September 13th General Scott ordered an infantry attack on the hill comprised of 3 assault columns. Some 500 infantrymen and marines stormed the hill. Among the Americans present were a young Captain Robert E. Lee and a young General Franklin Pierce. The Mexicans defended the hill valiantly, but a mere hour into the infantry attack General Bravo, assessing the situation as hopeless, ordered a retreat. All soldiers and cadets ceased fighting and evacuated their positions, except for 6 young cadets who would rather fight to the death than surrender. Mexican history remembers their names: Juan de la Barrera, Francisco Márquez, Agustín Melgar, Fernando Montes de Oca, Vicente Suárez and Juan Escutia.

Oldest of the 6 at age 19, Juan de la Barrera was born in Mexico City in 1828, the son of an army general. He became a cadet at Chapultepec when he was 12 years old and at the time of the Battle of Chapultepec he was a lieutenant in the military engineers and a part-time instructor at the military academy. He was defending the gun battery when the Americans attacked.

From Guadalajara, Jalisco, Francisco Márquez was the youngest of the Niños Héroes at age 13. Francisco became interested in the military when his mother remarried a cavalry captain named Francisco Ortiz. Francisco Márquez had entered the academy in January of 1847 at the age of twelve and belonged to the first company of cadets. He defended the east flank of the hill.

Agustín Melgar hailed from Chihuahua City, the capital of the northern Mexican state of the same name, and was the son of Esteban Melgar, a lieutenant colonel in the Mexican Army. As both his parents died when he was very young, Agustín was raised by his older sister until he entered the military academy in November of 1846. Alone, he defended the north side of the castle.

Fernando Montes de Oca was 15 years old at the time of the battle and was born in the town of Azcapotzalco which was located just north of Mexico City and is now considered one of the boroughs of the Distrito Federal. He had entered the academy in January of 1847 and was the only cadet left inside the castle to defend it.

Fernando Montes de Oca was 15 years old at the time of the battle and was born in the town of Azcapotzalco which was located just north of Mexico City and is now considered one of the boroughs of the Distrito Federal. He had entered the academy in January of 1847 and was the only cadet left inside the castle to defend it.

Vicente Suárez was 14 years old at the time of the battle. From Puebla, he was the son of a cavalry officer and was an officer cadet at the academy.

The last of the Child Heroes, and perhaps the most famous, was Juan Escutia. Born in Tepic, the capital of the state of Nayarit sometime between 1828 and 1832, he was admitted to the academy as a cadet just 4 days before the Battle of Chapultepec. He is often portrayed as being a second lieutenant in an artillery company, but his records, like most of those belonging to the cadets were lost in the battle and subsequent US takeover of Chapultepec.

All 6 of the Niños Héroes died of gunshot wounds while defending their positions except for the last one mentioned here, Juan Escutia. As the last one left alive on the hill and with the Americans moments away from his position, young Juan pulled the Mexican flag off the academy’s flagpole, wrapped himself in it and jumped off the hill rather than surrender to the enemy forces. His body was found on the eastern part of Chapultepec alongside that of his friend, Francisco Márquez.

Like all historical events, the story of the Child Heroes of Chapultepec Hill is not without controversy. The story of the 6 cadets who would rather fight to the death than surrender to the invaders has morphed over time and has taken on an almost religious significance in Mexican history. The Niños Héroes are almost regarded as saints in the national pantheon. Since the Battle of Chapultepec and since the story spread throughout the country, the cadets have been put under the microscope and examined. Emotions run high in the defense of the story even to this day, as evidenced by “flame wars” existing on the internet discussing whether this story is myth or history. The first serious examination by historians began in the late 1940s. Soon after President Truman’s visit, the bodies of 6 adolescent males were discovered in a shallow grave on the south side of Chapultepec Hill. Without any forensic testing, the government declared that it had discovered the bodies of the child heroes. The famous Mexican historian and archaeologist Eulalia Guzman Barron examined the remains and concluded that they were of young men attached to the San Blas or San Patricio regiments and not cadets from the military academy. The government at the time did not like her conclusions and to take the focus off this case officials sent Guzman to investigate claims that the remains of the last Aztec Emperor, Cuahutémoc, had been discovered. The Cuahutémoc distraction, not surprisingly, was a wild goose chase and Guzman’s interest in the Niños Héroes waned. In the years since Eulalia Guzman’s investigations others have tried to prove or disprove the story of the brave cadets with mixed results. Some claim that the story was started by  General Santa Ana to incite the Mexicans to fight more fiercely against the Americans. The 6 cadets have certainly been used for political purposes by many Mexican politicians across time. During the dictatorship of President Porfirio Díaz at the end of the 1800s, Díaz used the niños to reinforce a sense of national pride and it was during this time when the country went into a naming frenzy and started to call streets and schools after the child heroes. Records of these famous six are spotty at best, but much was lost during the battle and much of the documentation on all the cadets at the military academy does not exist. Whether real or myth or combining bits or pieces of both, a trip to Mexico City is not complete without a visit to Chapultepec Castle and a stop at the glistening white 6-pillared monument to honor the fallen cadets. It’s a solemn place that still evokes tears from Mexicans and Americans alike, and perhaps for good reason.

General Santa Ana to incite the Mexicans to fight more fiercely against the Americans. The 6 cadets have certainly been used for political purposes by many Mexican politicians across time. During the dictatorship of President Porfirio Díaz at the end of the 1800s, Díaz used the niños to reinforce a sense of national pride and it was during this time when the country went into a naming frenzy and started to call streets and schools after the child heroes. Records of these famous six are spotty at best, but much was lost during the battle and much of the documentation on all the cadets at the military academy does not exist. Whether real or myth or combining bits or pieces of both, a trip to Mexico City is not complete without a visit to Chapultepec Castle and a stop at the glistening white 6-pillared monument to honor the fallen cadets. It’s a solemn place that still evokes tears from Mexicans and Americans alike, and perhaps for good reason.

REFERENCES

“La versión oficial y otras teorías sobre la historia de los Niños Héroes” from the TV Pacifico website.

Various online sources.

2 thoughts on “The Child Heroes and the American Invasion of Mexico”

I read that the cadet’s suicide was a myth. Does anyone agrees with this?

I’ve heard that, too, or at least most of the story has been embellished.