Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

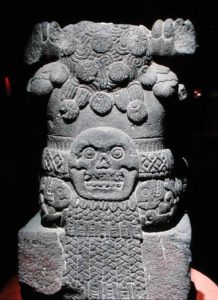

The 55-year-old Antonio de León y Gama shivered with excitement when he arrived at the southeast corner of the Zocalo on that hot August day in Mexico City. The year was 1790 and the capital city of colonial New Spain was buzzing with news of the discovery of a gigantic statue, almost 9 feet tall, of what appeared to be a hideous monster. Antonio de León was a noted astronomer, anthropologist and prolific writer on scientific topics. He was much respected in Mexico City and would later write a book about this statue and the Aztec calendar stone which was discovered nearby later that year. Breaking with the convention of previous Aztec chroniclers, in his book de León praised the ancient civilization that created the sculpture, which is seen by some historians as indicative of a growing sense of nationalism and Mexican pride in late 18th Century New Spain only a few decades away from Mexico’s independence. In the book, the author described the 9-foot-tall grotesque monster as the god Teoyamiqui. He had failed to notice the sagging breasts indicating a middle-aged woman and didn’t tie the snake imagery to the goddess to which it rightfully belonged: Coatlicue. Indeed, the massive carving clearly had a skirt made of writhing snakes and a belt tied at the ends with the heads of snakes. Her feet were claws with eyes and she wore a sacrificial necklace of severed human hands and torn-out hearts. She was decapitated with an artistic representation of spurting blood where her head should have been. To many people in Mexico City – those of European and mixed ancestry especially – the statue was perceived as anywhere from repulsive to demonic. As the word spread among the indigenous population of colonial Mexico City, however, the Coatlicue sculpture started to attract a special reverence. People began bringing offerings to her and lit candles at her clawed feet. As attention around the carving grew and so did its controversy, the viceroy himself ordered the statue to be reburied. A special site was selected in a patio at the University of Mexico and it was interred for good. That was until the visit of Alexander von Humboldt some 13 years later. In 1803, Coatlicue was brought to see the light of day again so that the visiting German scientist could make drawings and a plaster cast of her, after which she was reburied, but not for good. The goddess was dug up again 20 years later in a newly independent Mexico on the request of wealthy British naturalist and antiquarian William Bullock, who took her to London and displayed her at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly as part of an exhibition of artifacts from Mexico and the South Seas. The statue was later returned to Mexico and is now housed at the National Museum of Anthropology very close to the old Aztec heart of the city where she was first unearthed.

The 55-year-old Antonio de León y Gama shivered with excitement when he arrived at the southeast corner of the Zocalo on that hot August day in Mexico City. The year was 1790 and the capital city of colonial New Spain was buzzing with news of the discovery of a gigantic statue, almost 9 feet tall, of what appeared to be a hideous monster. Antonio de León was a noted astronomer, anthropologist and prolific writer on scientific topics. He was much respected in Mexico City and would later write a book about this statue and the Aztec calendar stone which was discovered nearby later that year. Breaking with the convention of previous Aztec chroniclers, in his book de León praised the ancient civilization that created the sculpture, which is seen by some historians as indicative of a growing sense of nationalism and Mexican pride in late 18th Century New Spain only a few decades away from Mexico’s independence. In the book, the author described the 9-foot-tall grotesque monster as the god Teoyamiqui. He had failed to notice the sagging breasts indicating a middle-aged woman and didn’t tie the snake imagery to the goddess to which it rightfully belonged: Coatlicue. Indeed, the massive carving clearly had a skirt made of writhing snakes and a belt tied at the ends with the heads of snakes. Her feet were claws with eyes and she wore a sacrificial necklace of severed human hands and torn-out hearts. She was decapitated with an artistic representation of spurting blood where her head should have been. To many people in Mexico City – those of European and mixed ancestry especially – the statue was perceived as anywhere from repulsive to demonic. As the word spread among the indigenous population of colonial Mexico City, however, the Coatlicue sculpture started to attract a special reverence. People began bringing offerings to her and lit candles at her clawed feet. As attention around the carving grew and so did its controversy, the viceroy himself ordered the statue to be reburied. A special site was selected in a patio at the University of Mexico and it was interred for good. That was until the visit of Alexander von Humboldt some 13 years later. In 1803, Coatlicue was brought to see the light of day again so that the visiting German scientist could make drawings and a plaster cast of her, after which she was reburied, but not for good. The goddess was dug up again 20 years later in a newly independent Mexico on the request of wealthy British naturalist and antiquarian William Bullock, who took her to London and displayed her at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly as part of an exhibition of artifacts from Mexico and the South Seas. The statue was later returned to Mexico and is now housed at the National Museum of Anthropology very close to the old Aztec heart of the city where she was first unearthed.

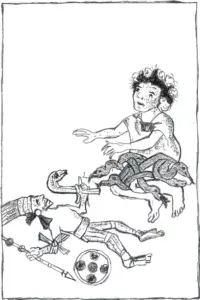

Made around 1500, a few decades before the Spanish Conquest of the Aztecs, the Coatlicue statue occupied a special place in the civic-ceremonial center of Tenochtitlan, the empire’s capital. This was perhaps because Coatlicue played such an important role in Aztec cosmology, especially with respect to the story of creation. There are a few versions of the creation story that existed among the Nahua peoples of central Mexico that became somewhat standardized and formalized under more centralized Aztec control. In the most common story of the current universe’s beginnings, Coatlicue was a young priestess who was the caretaker of a shrine on top of the sacred mountain called Coatepec, which means “Snake Mountain” in the Aztec language, Nahuatl. While she was sweeping a ball of hummingbird feathers fell from the sky. Seeing this as a rare thing, the young Coatlicue tucked the feathery mass into her belt at which point it miraculously impregnated her. She had already given birth to Coyolxauhqui, the powerful moon goddess, and to all the stars in the southern sky, Coatlicue’s 400 sons known as the Centzon Huitznahua. She gave birth to these gods by another miraculous conception: an obsidian knife had fallen from the skies and had impregnated her. Coatlicue’s offspring saw this new feather ball pregnancy as shameful and plotted to go to Snake Mountain to kill her. One of the 400 sons, a star being named Cuahuitlicac, felt remorse and before the storming of the mountain he went to Coatlicue to tell her of the plot. On hearing the news, the unborn child sprang forth from Coatlicue’s belly, fully armed and ready for battle. The newborn was Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war and patron of the Aztec Empire and he possessed the xiuhcoatl, or a “fire serpent,” which was a blazing ray of the sun. He also had with him a shield of feathers and turquoise darts to fight off his siblings. In another version of the story, it was too late for Coatlicue and Huitzilopochtli sprang from his mother’s severed head after the attack by her unruly offspring. In any case, the new war god swiftly defeated his siblings, and even chopped up his sister the moon goddess and threw her body parts down the mountain. He threw her head up in the sky to become the moon and scattered his 400 brothers across the Universe. Coatlicue, now dead, provided fertility for the earth with her decomposing body. The creation/destruction myth would be reenacted yearly at the Templo Mayor with dismembered sacrificial victims being thrown down the steps of the main pyramid as if it were Mount Coatepec. The story involving the death of Coatlicue and the birth of Huitzilopochtli is said to symbolize the daily victory of the sun over the moon and stars and the sacrificial nature of life on earth. Death must come to some to give life to others. In the annual Templo Mayor ceremony a living human heart was given up to Coatlicue so that she would continue to keep the earth fertile and would ensure that humanity would not die from starvation. To the Aztecs the sacrifices were necessary for the smooth functioning of the universe.

Made around 1500, a few decades before the Spanish Conquest of the Aztecs, the Coatlicue statue occupied a special place in the civic-ceremonial center of Tenochtitlan, the empire’s capital. This was perhaps because Coatlicue played such an important role in Aztec cosmology, especially with respect to the story of creation. There are a few versions of the creation story that existed among the Nahua peoples of central Mexico that became somewhat standardized and formalized under more centralized Aztec control. In the most common story of the current universe’s beginnings, Coatlicue was a young priestess who was the caretaker of a shrine on top of the sacred mountain called Coatepec, which means “Snake Mountain” in the Aztec language, Nahuatl. While she was sweeping a ball of hummingbird feathers fell from the sky. Seeing this as a rare thing, the young Coatlicue tucked the feathery mass into her belt at which point it miraculously impregnated her. She had already given birth to Coyolxauhqui, the powerful moon goddess, and to all the stars in the southern sky, Coatlicue’s 400 sons known as the Centzon Huitznahua. She gave birth to these gods by another miraculous conception: an obsidian knife had fallen from the skies and had impregnated her. Coatlicue’s offspring saw this new feather ball pregnancy as shameful and plotted to go to Snake Mountain to kill her. One of the 400 sons, a star being named Cuahuitlicac, felt remorse and before the storming of the mountain he went to Coatlicue to tell her of the plot. On hearing the news, the unborn child sprang forth from Coatlicue’s belly, fully armed and ready for battle. The newborn was Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war and patron of the Aztec Empire and he possessed the xiuhcoatl, or a “fire serpent,” which was a blazing ray of the sun. He also had with him a shield of feathers and turquoise darts to fight off his siblings. In another version of the story, it was too late for Coatlicue and Huitzilopochtli sprang from his mother’s severed head after the attack by her unruly offspring. In any case, the new war god swiftly defeated his siblings, and even chopped up his sister the moon goddess and threw her body parts down the mountain. He threw her head up in the sky to become the moon and scattered his 400 brothers across the Universe. Coatlicue, now dead, provided fertility for the earth with her decomposing body. The creation/destruction myth would be reenacted yearly at the Templo Mayor with dismembered sacrificial victims being thrown down the steps of the main pyramid as if it were Mount Coatepec. The story involving the death of Coatlicue and the birth of Huitzilopochtli is said to symbolize the daily victory of the sun over the moon and stars and the sacrificial nature of life on earth. Death must come to some to give life to others. In the annual Templo Mayor ceremony a living human heart was given up to Coatlicue so that she would continue to keep the earth fertile and would ensure that humanity would not die from starvation. To the Aztecs the sacrifices were necessary for the smooth functioning of the universe.

As with many Mesoamerican deities, Coatlicue had many other functions and aspects and also had other names. She is both destroyer and creator, mother of gods and the helper of mothers on earth. Like the earth, she feeds on corpses and consumes all that dies. Her snake skirt symbolizes fertility, as the image of the snake was so used by the Aztecs and other ancient Mexican cultures. She may appear as Cihuacóatl, the “snake woman,” a fearsome goddess of childbirth or as Tlazoltéotl, the deity of sexual misconduct. Coatlicue was also known as Teteoinnan, or “The Mother of the Gods,” or simply Toci, “Our Grandmother.” The latter term comes from the idea that in one version of the creation story, one of Coatlicue’s sons, Quetzalcoatl, created humans out of gray ash, thus making Coatlicue the grandmother of mankind. In any situation, the snake-skirted goddess was both revered and feared and her power stood the test of time. This was evident almost 300 years after the end of the Aztec Empire as seen in the reaction from Mexico City’s indigenous community to the unearthing of the massive Coatlicue statue. Some scholars allege that some aspects of Coatlicue still survive in the cult of the Santa Muerte, or “The Most Holy Death,” a grim-reaper-type folk saint that has gained popularity throughout Mexico since the 1960s and is especially relevant today. For more information on the Santa Muerte, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode # 9.

In Aztec legends there is a story of how Coatlicue predicted the end of the Aztec Empire. A few years before his fateful meeting with conquistador Hernán Cortés, so the story goes, Emperor Montezuma dispatched a party of 60 priests and magicians to the mythical northern land of Aztlán in search of the goddess to ask her questions about the future and to get greater knowledge of the present. The Aztec entourage almost made it to Coatlicue’s home in Aztlan, but they were so bogged down with gifts and provisions that they could not make it out of a troublesome patch of deep sand. While struggling to free themselves the goddess appeared to them and declared that the mighty Aztec cities would fall one by one. It was at that time that Huitzilopochtli would return to her side and the Aztecs would be finished. It is never known if the group of priests and magicians ever made it back to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, or even if the story was added to the native lore after the Spanish Conquest. It is true, though, that without the sacrifices and devotion paid to her Coatlicue did face a final death with the ultimate destruction brought about by the Spanish at the doomed Aztec capital.

In Aztec legends there is a story of how Coatlicue predicted the end of the Aztec Empire. A few years before his fateful meeting with conquistador Hernán Cortés, so the story goes, Emperor Montezuma dispatched a party of 60 priests and magicians to the mythical northern land of Aztlán in search of the goddess to ask her questions about the future and to get greater knowledge of the present. The Aztec entourage almost made it to Coatlicue’s home in Aztlan, but they were so bogged down with gifts and provisions that they could not make it out of a troublesome patch of deep sand. While struggling to free themselves the goddess appeared to them and declared that the mighty Aztec cities would fall one by one. It was at that time that Huitzilopochtli would return to her side and the Aztecs would be finished. It is never known if the group of priests and magicians ever made it back to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, or even if the story was added to the native lore after the Spanish Conquest. It is true, though, that without the sacrifices and devotion paid to her Coatlicue did face a final death with the ultimate destruction brought about by the Spanish at the doomed Aztec capital.

One thought on “Coatlicue, The Goddess with the Skirt of Snakes”

Thank you do much dear!! have a nice daytony clifton taxi