Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Diego de Landa, Bishop of Yucatán, had this to say about the Maya relationship with death in his 1566 work Relación de las cosas de Yucatán:

Diego de Landa, Bishop of Yucatán, had this to say about the Maya relationship with death in his 1566 work Relación de las cosas de Yucatán:

“The people had a great and excessive fear of death, and they showed this in that all the services, which they made to their gods, were for no other end, nor for any other purpose than they – the gods – should give them health, life and sustenance. But when, in time, they came to die, it was indeed a thing to see their sorrow and the cries which they made for their dead, and the great grief it caused them. During the day they wept for them in silence; and at night with loud and very sad cries, so that it was pitiful to hear them. And they passed many days in deep sorrow. They made abstinences and fasts for the dead, especially the husband or wife; and they said that the devil had taken him away since they thought that all evils came to them from him – the devil – and especially death.”

Bishop de Landa was famous for the 1562 burning of the Maya books discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 106: https://mexicounexplained.com/great-maya-book-burning/. While this was a tragic cultural loss for the Maya and the rest of humanity, Bishop de Landa also left us with a legacy of well-documented observations of the living Maya at the time immediately after the Spanish Conquest. This is not meant to excuse what he did by any means. Some of Landa’s writings give modern researchers important information about Maya material culture and beliefs from 500 years ago. Some of that information pertains to Maya deities, including the gods associated with death.

It’s important to note that the conquest of the Maya area of Mexico was much different from the conquest of central Mexico. When Cortés marched into the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, he was experiencing the Aztecs at the height of their culture and power. When the Spanish arrived in the Yucatán, the glories of the Classic Maya civilization had long since vanished, as the Classic Maya collapse happened some 500 years earlier. Because of this, it is harder to know what the exact beliefs of the Classic Maya were. Archaeologists and other researchers must piece together information from various places – such as stone inscriptions, pottery illustrations, and the few Maya books that escaped burning – to try to understand the religious beliefs of these complex people. The beliefs of the Maya encountered at the time of Conquest may or may not have been the same or similar to the ancient beliefs but may serve to provide clues as to what the Classic Maya believed. In the case of the Maya death gods, there may be threads going back over a thousand years that tie the more modern Maya with the ancients.

Landa in his writings referred to the Maya death god as “The Prince of the Devils” and claimed that the Maya people of the 16th Century called this god Hunhau. He is also described as “The Lord of the Underworld.” In other reference materials about the Maya written a few decades later show that the death god or “chief devil” of the Maya of the northern Yucatán was called Humhau or Cumhau. The name “Hunhau” has two interpretations. It may either mean “One Lord” or “Lay on His Back.” The name Hun Ahau appears in a Maya book of 42 incantations called the Ritual of the Bacabs which was written sometime in the 1770s but was most likely copied from earlier works. The Hun Ahau in the book of incantations is not specifically a death god, though, and researchers are confused by this. What’s more confusing is that at the time of the Spanish Conquest different Maya groups living in different geographical regions had other names for the god of death. To the Ch’ol Maya of the Chiapas highlands and the Lacandon Maya of the jungles of Chiapas and Guatemala, the death god was named Kisin. Kisin was also the god of earthquakes, and he would kick the pillars on which the world rested in the Underworld if he ever became angry. His name comes from the Maya word kis, meaning stench or flatulence. In some regions of the Yucatán at the time of the arrival of the Europeans, the death god was also called Yum Kimil. In some parts of modern-day Tabasco, Chiapas and Campeche, he is known as Ah Pukuh. It is probably from the name Ah Pukuh where a semi-modern name for the ancient Maya death god emerged in the scholarly texts beginning in the 1950s. This name – Ah Puch – spread erroneously as researchers copied each other and is still seen in some current books written about the ancient Maya. 21st Century scholars have discarded the name Ah Puch in favor of just naming the ancient Maya death gods with letters. Some researchers believe that there were two main death gods of the ancient Maya, now labeled God A and God A-Prime. Modern researchers believe that the Classic Maya God A corresponds to the “Prince of the Devils” Hunhau as described by Bishop de Landa 500 years later. God A-Prime loosely matches up with a minor god described by Diego de Landa called Uacmitun Ahau.

Landa in his writings referred to the Maya death god as “The Prince of the Devils” and claimed that the Maya people of the 16th Century called this god Hunhau. He is also described as “The Lord of the Underworld.” In other reference materials about the Maya written a few decades later show that the death god or “chief devil” of the Maya of the northern Yucatán was called Humhau or Cumhau. The name “Hunhau” has two interpretations. It may either mean “One Lord” or “Lay on His Back.” The name Hun Ahau appears in a Maya book of 42 incantations called the Ritual of the Bacabs which was written sometime in the 1770s but was most likely copied from earlier works. The Hun Ahau in the book of incantations is not specifically a death god, though, and researchers are confused by this. What’s more confusing is that at the time of the Spanish Conquest different Maya groups living in different geographical regions had other names for the god of death. To the Ch’ol Maya of the Chiapas highlands and the Lacandon Maya of the jungles of Chiapas and Guatemala, the death god was named Kisin. Kisin was also the god of earthquakes, and he would kick the pillars on which the world rested in the Underworld if he ever became angry. His name comes from the Maya word kis, meaning stench or flatulence. In some regions of the Yucatán at the time of the arrival of the Europeans, the death god was also called Yum Kimil. In some parts of modern-day Tabasco, Chiapas and Campeche, he is known as Ah Pukuh. It is probably from the name Ah Pukuh where a semi-modern name for the ancient Maya death god emerged in the scholarly texts beginning in the 1950s. This name – Ah Puch – spread erroneously as researchers copied each other and is still seen in some current books written about the ancient Maya. 21st Century scholars have discarded the name Ah Puch in favor of just naming the ancient Maya death gods with letters. Some researchers believe that there were two main death gods of the ancient Maya, now labeled God A and God A-Prime. Modern researchers believe that the Classic Maya God A corresponds to the “Prince of the Devils” Hunhau as described by Bishop de Landa 500 years later. God A-Prime loosely matches up with a minor god described by Diego de Landa called Uacmitun Ahau.

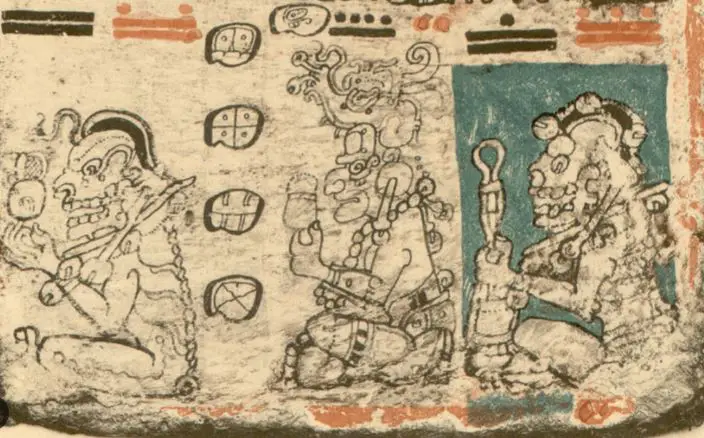

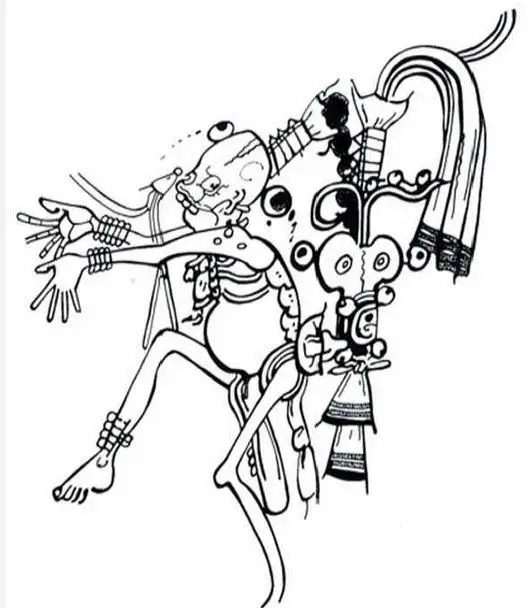

What can archaeologists tell us about the ancient Maya death gods labeled as God A and God A-Prime? The two gods were considered to be wayob, or shape-shifting creatures that could assume the forms of animals. Death God A appears 88 times in three existing ancient Maya codices, or bark paper books, and is the 4th god in frequency in these texts. He is depicted as having a skull for a head, bare ribs, and a spiny backbone. He is often clothed in flesh draped over his skeleton. God A is often seen bloated, and sometimes has decomposing matter pouring from his belly. He is often shown carrying a staff of what appears to be sleigh bells. Sometimes these bells are fastened to his hair or wrapped around his arms or legs. In some images they are draped around his neck. In the real world, these small bells, often made of copper, were found in abundance when the sacred well of Chichén Itzá was dredged, giving researchers a tangible connection to this powerful ancient god of death, as it is assumed that the bells accompanied sacrificial victims into the well. In many illustrations, God A is shown with scorpions, centipedes, spiders, vultures, owls, bats and other night creatures. Sometimes he is dancing or smoking cigarettes. Researchers believe that as a shapeshifter, God A could transform himself into a dog, an owl or other birds. God A’s name in the ancient Maya writing system consists of two name glyphs. The first glyph depicts the skull of a corpse with its eyes closed in death. The second glyph is the head of God A himself with a blunt nose, a fleshless jaw and a flint knife in front of him. God A is also associated with the number 10 and is honored in celebrations bringing in the new year.

What can archaeologists tell us about the ancient Maya death gods labeled as God A and God A-Prime? The two gods were considered to be wayob, or shape-shifting creatures that could assume the forms of animals. Death God A appears 88 times in three existing ancient Maya codices, or bark paper books, and is the 4th god in frequency in these texts. He is depicted as having a skull for a head, bare ribs, and a spiny backbone. He is often clothed in flesh draped over his skeleton. God A is often seen bloated, and sometimes has decomposing matter pouring from his belly. He is often shown carrying a staff of what appears to be sleigh bells. Sometimes these bells are fastened to his hair or wrapped around his arms or legs. In some images they are draped around his neck. In the real world, these small bells, often made of copper, were found in abundance when the sacred well of Chichén Itzá was dredged, giving researchers a tangible connection to this powerful ancient god of death, as it is assumed that the bells accompanied sacrificial victims into the well. In many illustrations, God A is shown with scorpions, centipedes, spiders, vultures, owls, bats and other night creatures. Sometimes he is dancing or smoking cigarettes. Researchers believe that as a shapeshifter, God A could transform himself into a dog, an owl or other birds. God A’s name in the ancient Maya writing system consists of two name glyphs. The first glyph depicts the skull of a corpse with its eyes closed in death. The second glyph is the head of God A himself with a blunt nose, a fleshless jaw and a flint knife in front of him. God A is also associated with the number 10 and is honored in celebrations bringing in the new year.

The other ancient Maya death god called God A-Prime has an interesting appearance equaling that of God A. He is easy to identify as he is always shown with black bands around his eyes. He often has a human femur bone in his elaborate headdress and is sometimes shown decapitating himself. In many illustrations God A-Prime is depicted carrying a staff and an orb much like modern-day Mexico’s folk saint called the Santa Muerte or Santisima Muerte discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 9: https://mexicounexplained.com/the-santa-muerte-death-respected/ God A-Prime usually wears a white loincloth and is decked out in ample jewelry, especially necklaces and bracelets. This deity is sometimes associated with a gigantic demonic insect of the ancient Maya called a Mokochih, of which little is known. This insect is often shown carrying a torch in its mouth and many researchers believe the Mokochih could have been some sort of shapeshifting wasp or firefly. The phonetic reading of God A-Prime’s name glyph is “Akan.” When the Spanish arrived in the Yucatán in the 1500s the Maya were worshipping a god called Akan, but it was the god of alcohol and drunkenness. Perhaps over the 500-year period between the Classic Maya Collapse and the arrival of the Spanish this god of death labeled A-Prime changed into something else as there is no alcohol imagery associated with the Classic God-A Prime. As with God A, A-Prime is associated with new year’s festivities. There are illustrations of Maya priests dressing up as this god to perform rituals connected with marking the new year.

While there are ample illustrations of the death gods, no one really knows what their functions were beyond the scant information already presented here. Did they guide all people to the Underworld? Were they considered hideous, malevolent beings to be feared? Were they welcoming assistants at the time of death? There are a lot of unanswered questions about these two and we do not know how the common people of the ancient Maya world related to them.

While there are ample illustrations of the death gods, no one really knows what their functions were beyond the scant information already presented here. Did they guide all people to the Underworld? Were they considered hideous, malevolent beings to be feared? Were they welcoming assistants at the time of death? There are a lot of unanswered questions about these two and we do not know how the common people of the ancient Maya world related to them.

Some researchers like to link the older Maya death gods to the gods of death written about in the famous Maya books composed well after the Spanish Conquest called the Popol Vuh and the Book of Chilam Balam. In the Popol Vuh, which is a Post-Hispanic take on the Maya creation story, we find two characters, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, also known as the Hero Twins, talked about in Mexico Unexplained episode number 85: https://mexicounexplained.com/hero-twins-maya-creation-story/ While in the Underworld, the twins are confronted by two death gods, one called Hun-Came and the other Vucub-Came. These more modern Maya death gods preside over a realm of diseased individuals, and the Hero Twins defeat them. As vanquished deities, Hun-Came and Vucub-Came are subject to the twins’ restrictions and new rules, so it seems like they were rather weak death gods. Some researchers like to link Hun-Came to God A and Vucub-Came to God A-Prime, but there is very little information in the post-Conquest Maya texts that would provide modern scholars to match them, such as how they looked or what animals they were associated with.

In the 21st Century, as half a millennium has passed since the Spanish Conquest, most modern-day Maya are left with fragments of folk tales about their old religion and conflicting stories that blend with Christianity in some cases. There is no direct living link to the old Maya gods of the pre-collapse times which makes it very difficult for researchers to understand even a fraction of the complexity of these early gods of death. As scholarship in the Maya world unfolds almost on a daily basis, perhaps someday soon researchers will be able to piece together clearer pictures of these enigmatic ancient Maya gods.

REFERENCES

Coe, Michael D. ‘Death and the Ancient Maya’, in E.P. Benson ed., Death and the Afterlife in Pre-Columbian America. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington 1975.

Stone, Andrea, and Marc Zender, Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2011. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3FBMfBl

Thompson, J. Eric S. Maya History and Religion. Civilization of the American Indian Series, No. 99. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.