Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

When thinking of the ancient civilizations of Mexico, besides thinking of impressive ruins and other artifacts left behind, we also think of their stargazing abilities and their fascination with time as shown in their calendar systems. Obsession with both astronomy and the recording of time seem to intersect when it comes to eclipses. How did ancient Mexican civilizations explain eclipses? How accurate were they at predicting them? How was this knowledge used? In this episode of Mexico Unexplained, we will take a look at three ancient cultures of Mexico – the Zapotec, the Maya and the Aztec – and explore how they explained and dealt with these heavenly phenomena.

When thinking of the ancient civilizations of Mexico, besides thinking of impressive ruins and other artifacts left behind, we also think of their stargazing abilities and their fascination with time as shown in their calendar systems. Obsession with both astronomy and the recording of time seem to intersect when it comes to eclipses. How did ancient Mexican civilizations explain eclipses? How accurate were they at predicting them? How was this knowledge used? In this episode of Mexico Unexplained, we will take a look at three ancient cultures of Mexico – the Zapotec, the Maya and the Aztec – and explore how they explained and dealt with these heavenly phenomena.

- The Zapotecs

The Zapotec civilization, which thrived from around 500 BC to 800 AD, represents one of Mesoamerica’s earliest and most influential cultures. Flourishing primarily in the valleys of Oaxaca in southern Mexico, they left an indelible mark on the region’s history and culture. Renowned for their advanced agricultural techniques, urban planning, and hieroglyphic writing system, the Zapotecs created a complex society characterized by monumental architecture, vibrant artistry, and spiritual depth. Their cities, including the renowned Monte Albán and Mitla, served as political and religious hubs where rulers governed from impressive pyramidal structures and temples adorned with intricate stone carvings.

Central to the Zapotec worldview was the belief that heavenly bodies exerted profound influences on human affairs and the natural world. The movements of the sun, moon, planets, and stars were meticulously observed and interpreted by Zapotec astronomers who developed sophisticated calendrical systems to track the passage of time and predict celestial events. Eclipses, specifically, were viewed as potent symbols of cosmic power and divine communication, signaling moments of great significance in the celestial hierarchy.

Solar eclipses, known as “nu dye yoo” or “darkening of the sun” in the Zapotec language have deep symbolic significance. According to the Zapotec creation story, at the dawn of time the sun and the moon were inseparable lovers whose radiant affection illuminated the entire sky. Concerned that their unified brilliance might engulf the world, the other gods intervened, orchestrating their separation to establish the cycles of day and night. Nonetheless, their eternal bond persists, manifested in the fleeting reunions witnessed during eclipses, serving as poignant reminders of their enduring passion within the hearts of mortals. While that is a somewhat endearing story, the Zapotecs believed that when this collision of sun and moon happened, bad things would follow. As in many other ancient Mexican cultures, there are often conflicting beliefs about the same thing or different stories used to explain things. For solar eclipses, sometimes Zapotecs believed that the sun god, who was a warrior by nature, was constantly fighting opposing forces in the sky and an eclipse represented the brief victory of darkness over the light. Lunar eclipses, known as “nu dye yoo guie” or “darkening of the moon,” were similarly interpreted as celestial struggles between the moon goddess and her adversaries, symbolizing the eternal cycles of life, death, and rebirth.

Solar eclipses, known as “nu dye yoo” or “darkening of the sun” in the Zapotec language have deep symbolic significance. According to the Zapotec creation story, at the dawn of time the sun and the moon were inseparable lovers whose radiant affection illuminated the entire sky. Concerned that their unified brilliance might engulf the world, the other gods intervened, orchestrating their separation to establish the cycles of day and night. Nonetheless, their eternal bond persists, manifested in the fleeting reunions witnessed during eclipses, serving as poignant reminders of their enduring passion within the hearts of mortals. While that is a somewhat endearing story, the Zapotecs believed that when this collision of sun and moon happened, bad things would follow. As in many other ancient Mexican cultures, there are often conflicting beliefs about the same thing or different stories used to explain things. For solar eclipses, sometimes Zapotecs believed that the sun god, who was a warrior by nature, was constantly fighting opposing forces in the sky and an eclipse represented the brief victory of darkness over the light. Lunar eclipses, known as “nu dye yoo guie” or “darkening of the moon,” were similarly interpreted as celestial struggles between the moon goddess and her adversaries, symbolizing the eternal cycles of life, death, and rebirth.

The Zapotecs demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of astronomy and celestial mechanics, which enabled them to predict the occurrence of eclipses with remarkable accuracy. Zapotec astronomers developed complex calendrical systems, such as the Monte Albán calendar, which allowed them to calculate the precise dates and times of celestial events, including eclipses. Inscriptions and codices found at Zapotec archaeological sites contain detailed records of eclipses, attesting to the meticulous observations and predictive capabilities of Zapotec astronomers.

- The Maya

The Classic Maya civilization, spanning from approximately 200 BC to 900 AD, represents the pinnacle of Maya cultural achievement in ancient Mexico. During this period, the Maya established powerful city-states or kingdoms in the regions of present-day southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. Renowned for their advancements in astronomy, mathematics, and hieroglyphic writing, the Maya constructed magnificent temple-pyramids, palaces, and ballcourts adorned with intricate carvings and glyphs. They developed sophisticated political systems, engaged in extensive trade networks, and created elaborate artworks, including stelae, ceramics, and codices, reflecting their profound spiritual beliefs and cultural sophistication.

Like the Zapotecs, the Maya observed, recorded and predicted eclipses. Central to the Maya worldview was the belief that the sun, the moon, the planets and the stars collectively exerted a powerful influence on human affairs and the natural world. The movements of the heavenly bodies were observed and recorded by Maya astronomers in great detail. Maya priests and scholars developed complex calendrical systems to track the passage of time and predict celestial events. Eclipses in Maya cosmology were interpreted as manifestations of supernatural forces and omens of great importance. Solar eclipses, known as “chi’ ibal kin” or “eating of the sun” in the Maya language, were believed to occur when celestial deities or monstrous creatures attempted to devour the sun, plunging the world into darkness. The Maya associated solar eclipses with the sun god Kinich Ahaw, who engaged in a perpetual cosmic struggle against the forces of darkness and chaos. Lunar eclipses, known as “chi’ ibal ish” or “eating of the moon,” were similarly viewed as cosmic battles between the moon goddess Ish Chel and her adversaries, symbolizing the eternal cycles of life, death, and rebirth. In the context of these beliefs eclipses were always associated with bad omens or bad luck, and an eclipse always had negative connotations to the Maya. As an interesting aside, to this day, as it was recorded in ancient times, some Maya people believe that an eclipse has the potential to have a negative effect on an unborn baby in the form of birth defects or miscarriage. Maya women who are pregnant during an eclipse are instructed to put a piece of obsidian on their bellies or in their mouths to ward off any evils associated with this celestial battle of good versus evil.

Like the Zapotecs, the Maya observed, recorded and predicted eclipses. Central to the Maya worldview was the belief that the sun, the moon, the planets and the stars collectively exerted a powerful influence on human affairs and the natural world. The movements of the heavenly bodies were observed and recorded by Maya astronomers in great detail. Maya priests and scholars developed complex calendrical systems to track the passage of time and predict celestial events. Eclipses in Maya cosmology were interpreted as manifestations of supernatural forces and omens of great importance. Solar eclipses, known as “chi’ ibal kin” or “eating of the sun” in the Maya language, were believed to occur when celestial deities or monstrous creatures attempted to devour the sun, plunging the world into darkness. The Maya associated solar eclipses with the sun god Kinich Ahaw, who engaged in a perpetual cosmic struggle against the forces of darkness and chaos. Lunar eclipses, known as “chi’ ibal ish” or “eating of the moon,” were similarly viewed as cosmic battles between the moon goddess Ish Chel and her adversaries, symbolizing the eternal cycles of life, death, and rebirth. In the context of these beliefs eclipses were always associated with bad omens or bad luck, and an eclipse always had negative connotations to the Maya. As an interesting aside, to this day, as it was recorded in ancient times, some Maya people believe that an eclipse has the potential to have a negative effect on an unborn baby in the form of birth defects or miscarriage. Maya women who are pregnant during an eclipse are instructed to put a piece of obsidian on their bellies or in their mouths to ward off any evils associated with this celestial battle of good versus evil.

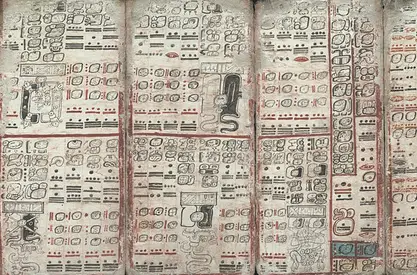

The Maya were renowned for their advanced knowledge of astronomy and mathematics, which enabled them to predict the occurrence of eclipses with remarkable accuracy. Maya astronomers developed sophisticated calendrical systems, such as the Long Count and the Tzolk’in, which allowed them to calculate the precise dates and times of celestial events, including eclipses. Inscriptions and codices found at Maya archaeological sites contain detailed records of eclipses, attesting to the meticulous observations and predictive capabilities of Maya astronomers. One such record is the 78-page Dresden Codex, a bark-paper book dating to the 11th or 12th Century which has a section devoted to describing and predicting eclipses. In fact, this Maya book accurately foretold the eclipse that crossed the Maya area on July 11, 1991, many hundreds of years before the event took place. Some scholars believe that the elites in the Maya realms kept books of eclipse predictions to engage in political manipulation, perhaps to show their inside knowledge of the workings of the gods to maintain power over their home populations or to garner political legitimacy in the eyes of rival kingdoms who did not have their own astronomers who were capable of making these seemingly amazing predictions.

- The Aztecs

Much is known of the Aztec civilization of ancient Mexico because of the three cultures examined here, the Aztec Empire was the only one that was a living and breathing entity at its height when the Spanish arrived. Like the Zapotecs and the Maya before them, the Aztecs had sophisticated methods of observing, tracking and predicting celestial events, and recorded these events in almanacs and through other written means. In the Aztec historical record, the first solar eclipse was noted to have occurred in the year 1155 AD, which was generations before the Aztecs left their ancestral homeland of Aztlán and made the long migration to central Mexico.

Much is known of the Aztec civilization of ancient Mexico because of the three cultures examined here, the Aztec Empire was the only one that was a living and breathing entity at its height when the Spanish arrived. Like the Zapotecs and the Maya before them, the Aztecs had sophisticated methods of observing, tracking and predicting celestial events, and recorded these events in almanacs and through other written means. In the Aztec historical record, the first solar eclipse was noted to have occurred in the year 1155 AD, which was generations before the Aztecs left their ancestral homeland of Aztlán and made the long migration to central Mexico.

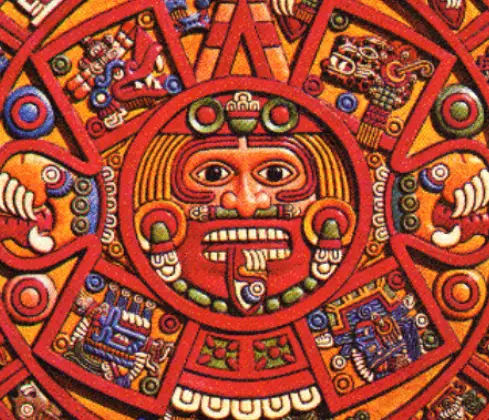

As with their gods and stories surrounding the creation of the world, there was great variety involved in what the Aztecs believed regarding eclipses. This may have to do with the vastness of their empire and the fact that they took in many religious beliefs and practices of subjugated peoples. In Aztec writings a normal sun glyph was depicted by a circle of concentric rings surrounded by outstretched rays. An eclipse was represented by a truncated sun glyph with dots attached as representations of stars. In the Aztec records of heavenly events, the eclipses are never pinned to an exact day, as they were in the Maya civilization. Eclipses were often recorded as occurring in a certain year during the reign of a specific emperor. Researchers can narrow down the exact date by correlating the Aztec eclipse tables with other eclipse records from around the world, such as those from Arabia, China or Europe.

The Aztecs had three major beliefs regarding solar eclipses. The first involved a gigantic jaguar in the sky who was eating the sun. An illustration of this can be found in the Aztec bark-paper book called the Codex Vaticanus. As the symbol of darkness, the jaguar imagery was quite fitting. The sun god then beats back the jaguar and restores the earthly realm to its normal daylight. The second major Aztec belief regarding eclipses involves a completely different idea that a type of “underworld” exists in the sky and because of the brightness of the sun, it cannot be seen. During the eclipse is the only time that the people of earth are able to peer into this underworld to see the dead according to this second take. The third belief regarding eclipses involves evil skeletal creatures of darkness who live in the sky and are collectively called the Tzitzimime. These creatures corresponded to the souls of enemy warriors who were captured and killed in sacrifice. They try to attack the sun god in an attempt to bring eternal darkness to the earth as revenge for their capture and death. During the darkness of the eclipse, it is believed, these evil skeleton creatures can descend to the earth and cause death and destruction. In this third belief of eclipses, the sun successfully slays the otherworldly creatures, of course, and a scene of the Tzitzimime battle with the sun can be found in the Florentine Codex. During times of eclipses, it was customary for the Aztec populace to stand beneath the blotted-out sun and make as much noise as possible by shouting or banging things to try to drive away the evil they were witnessing. They thought that there was a possibility that the sun would never be restored and making an earthly commotion must have been seen as better than standing around doing nothing.

The Aztecs had three major beliefs regarding solar eclipses. The first involved a gigantic jaguar in the sky who was eating the sun. An illustration of this can be found in the Aztec bark-paper book called the Codex Vaticanus. As the symbol of darkness, the jaguar imagery was quite fitting. The sun god then beats back the jaguar and restores the earthly realm to its normal daylight. The second major Aztec belief regarding eclipses involves a completely different idea that a type of “underworld” exists in the sky and because of the brightness of the sun, it cannot be seen. During the eclipse is the only time that the people of earth are able to peer into this underworld to see the dead according to this second take. The third belief regarding eclipses involves evil skeletal creatures of darkness who live in the sky and are collectively called the Tzitzimime. These creatures corresponded to the souls of enemy warriors who were captured and killed in sacrifice. They try to attack the sun god in an attempt to bring eternal darkness to the earth as revenge for their capture and death. During the darkness of the eclipse, it is believed, these evil skeleton creatures can descend to the earth and cause death and destruction. In this third belief of eclipses, the sun successfully slays the otherworldly creatures, of course, and a scene of the Tzitzimime battle with the sun can be found in the Florentine Codex. During times of eclipses, it was customary for the Aztec populace to stand beneath the blotted-out sun and make as much noise as possible by shouting or banging things to try to drive away the evil they were witnessing. They thought that there was a possibility that the sun would never be restored and making an earthly commotion must have been seen as better than standing around doing nothing.

Eclipses held a central place in the cosmology and religious worldview of ancient Mexican civilizations, serving as potent symbols of cosmic power and divine intervention. Through myth, ritual, and astronomical knowledge, the Zapotecs, Maya, Aztecs and other cultures sought to make sense of these awe-inspiring events, weaving them into the fabric of their cultural identity and leaving behind a legacy of celestial wisdom that continues to inspire awe and wonder to this day.

REFERENCES

Justeson, J. “Colonial Zapotec Calendars and Calendrical Astronomy.” In: Ruggles, C. (eds) Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. 2015.

Khalisi, Emil. Eclipses in the Aztec Codices. Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Press, 2020.

Worthington, Danika. “Mayans Predicted Solar Eclipses Hundreds of Years into the Future.” in The Denver Post, 17 Aug 2017.