Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Buy the show’s official t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/new-el-cucuy?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=2&cid=568

Buy the show’s official t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/new-el-cucuy?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=2&cid=568

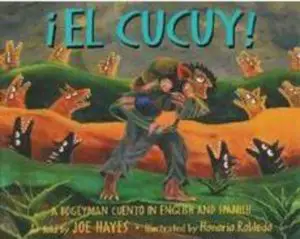

In the year 2001 Cinco Puntos Press out of El Paso published the bilingual children’s book El Cucuy written by Pennsylvania-born Joe Hayes. Hayes, who had lived in the American Southwest since his childhood is the consummate storyteller and collector of legends and folk tales. It was Hayes’ book that finally brought the Cucuy out from under the beds and out of the dark closets of Mexican children’s rooms and into the light of day of the English-speaking world. (Buy the book at a discount here: https://amzn.to/2NH7DMt) What’s been called the Mexican version of the Bogeyman has been terrifying children throughout the Hispanic world for centuries and possibly thousands of years. While few think the Cucuy is based on a real creature, some may be surprised to learn that the creature’s origins go back to prehistoric Celtic Europe. So, what is the Cucuy? What does it look like? What purpose does this legend serve?

We can start with the story of the Cucuy as related by Joe Hayes in his groundbreaking children’s book. In “once upon a time” fashion, there was once a man who lived in a small Mexican village with his three daughters. His wife had died and the man was left to raise his three girls on his own. The youngest of the three daughters was very helpful around the house, recognizing that without their mom around their father was left to spend 12-hours a day working along with all the other responsibilities of two parents. The older daughters saw their younger sister as somewhat of a chump or a goody two-shoes. The older girls were always out playing or doing whatever they wanted while the younger girl was stuck doing the chores. When the younger girl pleaded for help from her sisters, she was met with laughter and derision. One day the younger daughter went to her father to plead with him to force the other girls to help her, but that only made matters worse for her. The older sisters began to sabotage the younger girl’s work: throwing ash from the fireplace on the newly cleaned floor, or tying into knots fresh laundry drying on the clothesline. The father, tired of the antics of the older girls and their attitude of overall laziness, threatened to call the Cucuy to come and get them. The older girls thought this to be funny. They had heard of this creature before. It was described as being tall and furry with red eyes and a peculiar red ear that was bigger than its normal ear. It was with this big red ear that the creature could hear misbehaving children, some said from a  distance of 250 miles. This snarling creature would abduct bad children, take them to his cave in the mountains and eventually eat them, and this served as a lesson to the young children. The older sisters mocked this fairytale and didn’t take the father’s threats seriously. When the father heard of his daughters’ continued bad behavior, he went outside and called out to the Cucuy by name. This made the two older girls even more irreverent and they continued to make fun of the situation and torment their younger sister. Then, townsfolk reported seeing a large upright hairy creature enter their little village. The creature made a beeline to the house of the widower and snatched the two older girls. The Cucuy swiftly took the girls to his mountain hideaway, a dark cave with a deep pit. He put the girls in the pit and fed them one tortilla per day, enough to barely keep them alive. After about a week, a goatherd tending his flock on the mountain went to rescue a goat of his that had its hoof stuck between two rocks. After the goat was freed and finished bleating for help, the goatherd heard the wailing sounds of the two girls inside the pit. The goatherd entered the cave and rescued the two, taking them down the mountain and back into town. The disobedient daughters were reunited with their father and little sister and begged the man never to call the Cucuy on them again. The father never did because the girls never gave him reason to. From then on, the girls helped out around the house and stopped being mean to their little sister. As a postscript to this story, all three girls eventually married and had families of their own, never leaving the area. Today, that little Mexican town is home to the great-great-great grandchildren of the three sisters and it is known throughout Mexico for having the most polite and well-behaved children anywhere in the country because no one wants the Cucuy to return.

distance of 250 miles. This snarling creature would abduct bad children, take them to his cave in the mountains and eventually eat them, and this served as a lesson to the young children. The older sisters mocked this fairytale and didn’t take the father’s threats seriously. When the father heard of his daughters’ continued bad behavior, he went outside and called out to the Cucuy by name. This made the two older girls even more irreverent and they continued to make fun of the situation and torment their younger sister. Then, townsfolk reported seeing a large upright hairy creature enter their little village. The creature made a beeline to the house of the widower and snatched the two older girls. The Cucuy swiftly took the girls to his mountain hideaway, a dark cave with a deep pit. He put the girls in the pit and fed them one tortilla per day, enough to barely keep them alive. After about a week, a goatherd tending his flock on the mountain went to rescue a goat of his that had its hoof stuck between two rocks. After the goat was freed and finished bleating for help, the goatherd heard the wailing sounds of the two girls inside the pit. The goatherd entered the cave and rescued the two, taking them down the mountain and back into town. The disobedient daughters were reunited with their father and little sister and begged the man never to call the Cucuy on them again. The father never did because the girls never gave him reason to. From then on, the girls helped out around the house and stopped being mean to their little sister. As a postscript to this story, all three girls eventually married and had families of their own, never leaving the area. Today, that little Mexican town is home to the great-great-great grandchildren of the three sisters and it is known throughout Mexico for having the most polite and well-behaved children anywhere in the country because no one wants the Cucuy to return.

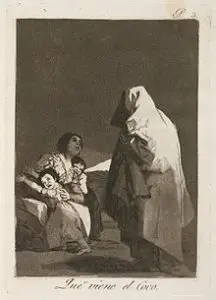

There are many variations to this story and in various versions of the legends the Cucuy can be a hairy wolfman-like creature – as in the Joe Hayes retelling – or an old man, a ghost or a large reptilian being. In some stories the Cucuy is cloaked, much like the Grim Reaper. In other stories he is carrying a skull or something like a jack-o-lantern that resembles a skull. Yet in other stories the Cucuy is a severed head. The lack of a uniform description of the creature and the various ways in which the legend is told suggest a very ancient and diffused origin. The only thing that all of the Cucuy stories have in common has to do with their use as a deterrent or punishment for bad behavior of children. The overall message, like the bogeyman of the English-speaking world, is that if you misbehave or disobey adults, the Cucuy will come after you to take you away and the consequences are severe.

There are many variations to this story and in various versions of the legends the Cucuy can be a hairy wolfman-like creature – as in the Joe Hayes retelling – or an old man, a ghost or a large reptilian being. In some stories the Cucuy is cloaked, much like the Grim Reaper. In other stories he is carrying a skull or something like a jack-o-lantern that resembles a skull. Yet in other stories the Cucuy is a severed head. The lack of a uniform description of the creature and the various ways in which the legend is told suggest a very ancient and diffused origin. The only thing that all of the Cucuy stories have in common has to do with their use as a deterrent or punishment for bad behavior of children. The overall message, like the bogeyman of the English-speaking world, is that if you misbehave or disobey adults, the Cucuy will come after you to take you away and the consequences are severe.

In some parts of the Spanish-speaking world, including some parts of the American Southwest, the Cucuy is known as the Coco or Coco-Man. Language historians have traced the origin of this word. “Cucuy” from “coco” has its origins in the Iberian Peninsula, specifically the country of Portugal and the far northwestern province of Spain, Galicia. The language of Galicia, called Galego, which is similar to Portuguese, shares a word with that language: côco. This word was used to refer to a ghost with the head of a pumpkin and is colloquially used to describe a head. Linguists believe this comes from a proto-Celtic word krowka or cróca meaning “head.” In some of the remaining Celtic languages of Europe, which are also on the Atlantic fringes of the continent, we still see variations of this word. In England, the Cornish language of the far southwestern part of Great Britain has the word crogen, meaning “skull.” Breton, an old Celtic language considered “severely endangered” by UNESCO and still spoken by less than 200,000 people in the far western part of Brittany on France’s Atlantic coast, the phrase krogen ar penn also means “skull.” The language history of the word Cucuy may point to an older Celtic origin of this legend and the story may have survived in the remaining Celtic communities on the Atlantic fringes of Europe, like Portugal and Galicia, and even survived their absorption by encroaching Latin-based cultures. There is no doubt that the story goes back thousands of years.

The first written record of what would become the Cucuy is found in a book from Portugal dating to the year 1274 called Livro 3 de Doações de Dom Afonso Terceiro, or in English, Book 3 of Grants of King Alfonso the Third. The “Coca” is described as a malignant sea creature. There are other sources from hundreds of years ago in the Iberian Peninsula describing the Coco or Coca as a large semi-aquatic reptile with spikes and a shell like a gigantic tortoise. The Cuca Fera was described this way and survived on a daily diet of three cats and three bad children. In the 1400s in the areas of modern-day Portugal and some parts of modern-day Spain, the Coco was often symbolized by something representing a severed head. A hollowed out vegetable was often carved with a scary face to represent the creature, or a severed head may have been carved of wood or fashioned out of clay to scare children to believe in this Cucuy pototype. Our very word in English “coconut” comes from the Portuguese legend of the severed head of the Coco, and this fruit was so named when it was first encountered by the ships captained by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in the late 1400s.

The first written record of what would become the Cucuy is found in a book from Portugal dating to the year 1274 called Livro 3 de Doações de Dom Afonso Terceiro, or in English, Book 3 of Grants of King Alfonso the Third. The “Coca” is described as a malignant sea creature. There are other sources from hundreds of years ago in the Iberian Peninsula describing the Coco or Coca as a large semi-aquatic reptile with spikes and a shell like a gigantic tortoise. The Cuca Fera was described this way and survived on a daily diet of three cats and three bad children. In the 1400s in the areas of modern-day Portugal and some parts of modern-day Spain, the Coco was often symbolized by something representing a severed head. A hollowed out vegetable was often carved with a scary face to represent the creature, or a severed head may have been carved of wood or fashioned out of clay to scare children to believe in this Cucuy pototype. Our very word in English “coconut” comes from the Portuguese legend of the severed head of the Coco, and this fruit was so named when it was first encountered by the ships captained by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in the late 1400s.

Some stories of the Cucuy or the Coco have the creature wearing a cloak like the Grim Reaper, the pan-European harbinger of death. This element may come from yet another old Iberian source. In old Portugal as part of the celebrations for Holy Week called Procissão dos Passos a hooded man heads a procession to announce the death of Christ. The man was either called Coca or Farricoca, and the word “coca” was also used to describe the hood the man wore. Also in Portugal, the hooded people called Farricoca were responsible for gathering the remains of people who were recently executed. There is an interesting tie-in here between some of the legends of the cloak-wearing Cucuy and those involved in morbid aspects of the Catholic religion.

Some stories of the Cucuy or the Coco have the creature wearing a cloak like the Grim Reaper, the pan-European harbinger of death. This element may come from yet another old Iberian source. In old Portugal as part of the celebrations for Holy Week called Procissão dos Passos a hooded man heads a procession to announce the death of Christ. The man was either called Coca or Farricoca, and the word “coca” was also used to describe the hood the man wore. Also in Portugal, the hooded people called Farricoca were responsible for gathering the remains of people who were recently executed. There is an interesting tie-in here between some of the legends of the cloak-wearing Cucuy and those involved in morbid aspects of the Catholic religion.

This heavily Portuguese legend probably came to Mexico in the late 1500s during what has been called by historians, “The Union of the Crowns.” Between 1580 and 1640, Spain and Portugal were united under the Hapsburg Spanish kings. Not only were the kingdoms combined, so were their overseas empires. The colony of New Spain saw much Portuguese immigration during this period and early versions of the Cucuy legend probably came off the ships along with the new passengers from Portugal. Like legends do, the Portuguese Coco slowly changed to meet local conditions. It was no longer so reptilian. The cloak was optional. The Mexican Cucuy has more of a tendency to be a large furry creature with fangs and claws, much like the shape-shifting Nagual of the ancient Aztecs and their subjugated peoples. With the recent increase of immigration from Latin America to the United States, the story of the Cucuy has officially entered new territory. It will be interesting to see what will happen in the upcoming decades as this ancient Iberian legend becomes Americanized. Throughout its many changes before and after its arrival to the New World and across geographical areas, the Cucuy has never deviated from its main purpose to terrify children into obedience. Modern-day parenting experts caution adults from frightening children with stories like the Cucuy and claim the use of such scary stories to get compliance from the young is a form of mental child abuse. In spite of this, there is no indication that the Cucuy will be killed off anytime soon.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

El Cucuy by Joe Hayes We are an Amazon affiliate.Get the Cucuy book by Joe Hayes at a discount here: https://amzn.to/2NH7DMt

“El Cucuy,” article found on Leyendasweb.com

Various online sources, including Wikipedia

13 thoughts on “El Cucuy, the Mexican Bogeyman”

This is crazy interesting. I hope you simply this entire story into a documentary or something.

Hi Omar. Thanks for listening. This will be a chapter in my new book.

And,then,there’s, “la llorona.”

That was Mexico Unexplained Episode #2. Available here.

Yes la llorona. Every week I was told that story. I still put the covers over my head. As I know if she can’t see you; she won’t get you.

cucuy viene para ti cucuy te comerá entero

cucu cawcaw ee ee awaw REEEEE

the cuccy is my friend

wtf

same

i swear la llorona would scare me so bad my parent would be like ey si no te portas bien te va llevar ese señor

ha me too very interesting

There is a food truck or food place in Denton, TX, with the name El Cucuy. Why would anyone do that? Also, it needs to be sent after a few politicians but it could give El Cucuy a bad bellyache.